Abstract

Background and purpose — People with cerebral palsy (CP) often have painful deformed hips, but they are seldom treated with hip replacement as the surgery is considered to be high risk. However, few data are available on the outcome of hip replacement in these patients.

Patients and methods — We linked Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) records to the National Joint Registry for England and Wales to identify 389 patients with CP who had undergone hip replacement. Their treatment and outcomes were compared with those of 425,813 patients who did not have CP. Kaplan-Meier estimates were calculated to describe implant survivorship and the curves were compared using log-rank tests, with further stratification for age and implant type. Reasons for revision were quantified as patient-time incidence rates (PTIRs). Nationally collected patient-reported outcomes (PROMS) before and 6 months after operation were compared if available. Cumulative mortality (Kaplan-Meier) was estimated at 90 days and at 1, 3, and 5 years.

Results — The cumulative probability of revision at 5 years post-surgery was 6.4% (95% CI: 3.8–11) in the CP cohort as opposed to 2.9% (CI 2.9–3%) in the non-CP cohort (p < 0.001). Patient-reported outcomes showed that CP patients had worse pain and function preoperatively, but had equivalent postoperative improvement. The median improvement in Oxford hip score at 6 months was 23 (IQR: 14–28) in CP and it was 21 (14–28) in non-CP patients. 91% of CP patients reported good or excellent satisfaction with their outcome. The cumulative probability of mortality for CP up to 7 years was similar to that in the controls after stratification for age and sex.

Interpretation — Hip replacement for cerebral palsy appears to be safe and effective, although implant revision rates are higher than those in patients without cerebral palsy.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is common, with a prevalence of 2 in 1,000 births (Oskoul et al. Citation2013). Between 25% and 75% of patients with CP have painful hips (Bagg et al. Citation1993). Muscle imbalance around the hip causes contractures and secondary bony changes, predominantly femoral neck valgus and anteversion, as well as subluxation resulting in femoral head deformity and eventual dislocation. In addition to pain, these patients also have problems with walking and, in more severe cases, with sitting. Some patients therefore undergo hip surgery in an attempt to address their pain and functional limitations. Traditionally, patients have been treated with excisional arthroplasty, which simply consists of removing the painful joint. Excision arthroplasty results in a short limb and poor overall function (Castle and Schneider Citation1978), but it can give satisfactory results in non-ambulatory patients (Egermann et al. Citation2009). An alternative to excising the hip joint in these patients is joint replacement, including hip resurfacing (Prosser et al. Citation2012).

Hip replacement in patients with CP is considered high risk, however, with concerns regarding fracture due to abnormal bony anatomy, and dislocation due to spasticity. However, little is known about the outcomes of total hip replacement for patients with cerebral palsy.

The National Joint Registry for England and Wales (NJR) has recorded all hip and knee replacements performed in England and Wales since April 2003, and it currently has over 1.5 million records. The NJR was estimated to capture 97% of cases in 2013. The Hospital Episodes Statistics database records all in-patient admissions, including all diagnoses. By combining the NJR with HES, we were able to identify patients with CP who had undergone THR in English NHS units since April 2003. We could then compare this group with those who had undergone THR for osteoarthritis and did not have CP.

We wanted to determine the incidence of THR in CP patients, whether there was any variation in provision between units, and the outcome of treatment.We hypothesized that revision rates would be higher in CP patients than in others, particularly for fracture and dislocation, and that patient-reported outcomes (PROMS) would be worse.

Patients and method

We used data from the NJR for the period April 1, 2003 to December 31, 2012. A linked data set, consisting of 539,372 primary hip replacements linked to first revisions (as described in Part 3 of the tenth annual report of the NJR) was linked to a contemporary HES extract to establish the baseline population that could be analyzed. Our HES extract documented all admissions to English hospitals for NHS-funded procedures from April 1997 (at least 5 years before any primary operation in NJR) up to the end of November 2012. 426,202 NJR cases (79.0%) had corresponding HES records. Patients with CP were identified from this linked dataset by searching for the ICD-10 code G80 appearing in any diagnosis field over the previous 5 years in any HES record for each patient (n = 389). The remaining non-CP cases (n = 425,813) were taken as controls for comparison.

The 2 groups, CP and control, were compared with respect to age at primary operation, sex, and type of implant used (including bearing surface). Also, for the CP cohort, implant use per year and numbers of operations by surgical units and surgeon were reported.

Our outcomes included implant survivorship regarding the need for a first revision procedure, together with PROMS and 90-day mortality. Dates of any deaths had been obtained from the Office of National Statistics when the annual report data set was assembled (March 2013).

PROMS data for hip and knee replacements have been collected routinely by all providers of NHS-funded care in England since April 2009. Q1 questionnaires are usually administered just before the operation and Q2 approximately 6 months afterwards (see http://www.hscic.gov.uk/PROMS). Our PROMS were obtained contemporaneously with the NJR Annual Report data set in March 2013 and details of how we linked to unilateral primary hip operations in the NJR dataset were given in part 3.5 of the tenth annual report (2013). PROMS data were available for 124,111 of the 426,202 primary hip replacements described above, i.e. 57.4% of 216,265 primary replacements performed since April 1, 2009. We focused on the Oxford hip score (OHS), based on scored responses to 12 specific questions about the previous 4 weeks, which were summed to give a total score from 0 (worst) to 48 (best); the EQ-5D Health score, a visual analog scale describing how the patients rated themselves “on the day” (0 = worst; 100 = best); and the EQ-5D index, derived from a profile of responses to 5 questions about health “today”, covering activity, anxiety/depression, discomfort, mobility and self-care, with responses weighted and added to produce an index with 1 being the maximum (best) score. We also looked at specific questions asked at Q2 about the patient’s overall satisfaction with the surgery and interim events, such as wound problems or bleeding (Table 5, see Supplementary data).

NJR data are validated against implant sales, and case ascertainment is recorded as 96% in the twelvth annual report of the National Joint Registry. Patient consent to record their details was 93.8% and linkability (the ability to link a patient’s primary procedure to a revision procedure) was recorded as 92.8%.

Statistics

Kaplan-Meier estimates were calculated to describe implant survivorship (cumulative probability of revision) with pointwise 95% confidence intervals (CIs); curves for the 2 cohorts were compared using a log-rank test, with further stratification for sex/age at primary arthroplasty (< 55, 55–64, 65–74, and 75 + years) together and also for implant type (fixation), both of which were known to influence outcome.

To compare the 2 groups regarding reasons for revision (which were not mutually exclusive), patient-time incidence rates (PTIRs) were calculated, i.e. numbers of revisions for each of the reasons stated divided by the total time at risk for all patients.

As our 3 main PROMS outcomes are known to have very different distributions at Q1 and Q2 (with known ceiling effects in the latter), non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-tests were used to compare the 2 groups and chi-squared tests were used for the additional Q2 questions.

For bilateral procedures (both sides implanted on the same day), both procedures were included in the implant survival because revision was assessed separately for the 2 implants. In the case of mortality, however, the second of each of the pairs of bilateral procedures was excluded. Our linked PROMS were for unilateral procedures only.

Results

We identified 389 total hip replacements in the CP cohort and 425,813 control replacements. Only 2 of the CP patients (4 implants or 1% of all CP primary arthroplasties) had the operations on the same day, i.e. were bilateral. Similarly, 2,106 of the control patients (4,212 implants or 1% of the implants) were bilateral.

Age/sex demographic

The sex distribution was similar, with 59% female in the CP group as compared to 60% in the control group. The CP cohort was younger, with a median age of 53 (IQR: 40–64) years as compared to 69 (IQR: 61–76) years in the controls (Figure 3, see Supplementary data). Information on age was missing in 135 of the control cases (as they could not be validated) and 1 case was of unknown gender.

Implant use

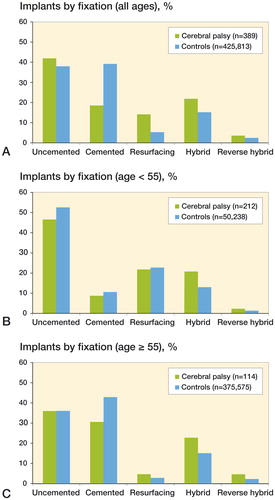

Implant use differed quite markedly between the CP group and the control group ( and ). In particular, resurfacing and uncemented hip replacements were used more frequently in patients with CP. Implant usage in the CP cohort changed over time. In particular, the use of ceramic-on-ceramic bearings increased substantially in 7 years, from 8% of cases in 2005 to 40% in 2012, and resurfacing decreased from 23% of cases in 2005 to 2% in 2012.

Table 1. Bearing surface used for the primary implants in the CP and control cohorts

Unit caseload

453 units recorded at least 1 primary hip operation in the baseline dataset (CP group and control group combined). 151 units (33% of all units) recorded at least 1 hip replacement on a patient with CP and 69 (15% of all units) recorded more than 1 primary hip operation on a patient with CP. 2 units in particular performed more hip replacements on patients with CP (33 and 19 cases). These 2 units together accounted for 13% of all primary arthroplasties identified in CP patients over the entire study period.

Surgeon caseload

In the baseline dataset, 4,531 surgeons recorded at least 1 primary total hip replacement. 265 surgeons (6% of all surgeons) carried out at least 1 hip primary hip replacement on patients with CP. 61 surgeons (1% of all surgeons) carried out more than 1 primary hip replacement on patients with CP. 1 lead surgeon in particular performed 22 primary hip replacements on patients with CP (6% of the operations in the CP cohort).

Implant survivorship

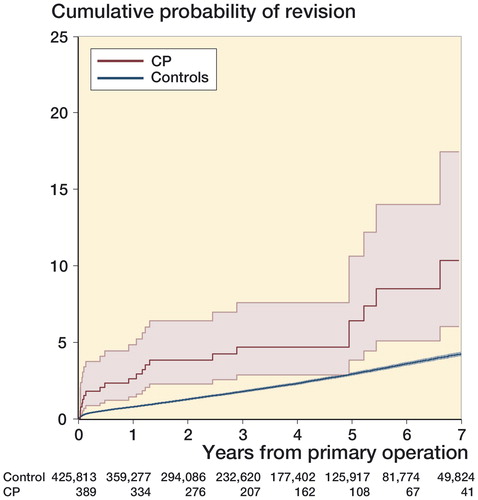

There were 22 revisions in the CP cohort, 10 of which failed within 1 year of the primary operation. There were 9,776 revisions in the control cohort, 3,212 (33%) of which failed within 1 year. The cumulative probability of revision at 1 year (Kaplan-Meier) was 2.6% (CI: 1.4–4.8) in the CP group as compared to 0.79% (CI: 0.76–0.82) in the controls (). CPs had higher revision rates at least up to 7 years post-surgery, although the number at risk had fallen by this time (overall log-rank test, to the maximum follow-up of 9.75 years, p < 0.001) (). The corresponding rates at 5 years were 6.4% (CI: 3.8–10.6) in CP patients and 2.9% (CI: 2.9–3) in controls.

Figure 2. Cumulative probability of revision (Kaplan-Meier, with pointwise 95% CIs) for CP vs. control patients.

Table 2. Cumulative percentage revised (Kaplan-Meier) for CP and control patients at 1, 3, and 5 years after primary operation, for all cases and by implant type (fixation)

At 5 years, the cumulative percentage probability of revision in the CP group was lowest with the use of cemented prostheses (1.5%, CI: 0.2–10.1) and hybrid prostheses (1.2%, CI: 0.2–8.1) and highest with uncemented prostheses (7.1%, CI: 3.7–13.4) and resurfacing prostheses (11.5%, CI: 4.5–27.4).

The most common reasons for revision in the CP cohort were periprosthetic fracture (7 cases, PTIR 5.0 (CI: 2.4–10.5) per 1,000 patient-years), aseptic loosening (6 cases, PTIR 4.3 (CI: 1.9–9.6)), pain (5 cases, PTIR 3.6 (CI: 1.5–8.6), and dislocation (4 cases, PTIR 2.9 (CI: 1.1–7.6)). Although the numbers were too small for meaningful statistical analysis, the rates of revision for pain, dislocation/subluxation, aseptic loosening, and periprosthetic fracture were all elevated compared to the controls (Table 4, see Supplementary data). The corresponding PTIRs in the control cohort were periprosthetic fracture, 0.70 (CI: 0.66–0.75); aseptic loosening, 1.60 (CI: 1.54–1.66); pain, 1.37 (CI:1.32–1.43); and dislocation, 1.22 (CI: 1.16–1.27).

There was a correlation between implant survivorship and age and sex, and the difference between CP patients and controls remained statistically significant after stratification for these (log-rank test, p = 0.008). However, when the age and sex subgroups were plotted separately, while the CP subgroup sizes were small, there was a higher cumulative probability of revision in the CP patients in each subgroup except for women aged ≥ 55 years (Figure 4, see Supplementary data; note that the 3 age groups ≥ 55 years have been combined for simplicity).

For each implant type, patients with CP generally showed worse implant survival but the numbers were small. The differences between CP patients and controls remained statistically significant when adjusted for hip type (stratified log-rank test, p = 0.008) (; summary statistics for age and gender are shown for the comparison groups).

Patient-reported outcomes (PROMS)

The numbers of cases for which there were associated PROMS data in the 2 groups were 98 (25.2%) of the 389 CP cases and 124,013 (29.1%) of the 425,813 controls cases.

The PROMS data on satisfaction and overall success were similar in the 2 groups. Regarding satisfaction in the CP cohort, 41% reported excellent results, 26% very good, 24% good, 5.6% fair, and 3.7% poor. In the control cohort, 39% reported excellent results, 35% very good, 18% good, 6.3% fair, and 1.9% poor. Urinary tract problems and re-admission rates were greater in the CP group (24% in CP patients vs. 13% in the controls (p = 0.03) and 16% in CP patients vs. 7% in the controls (p = 0.01), respectively). For further details, see Table 5 (Supplementary data) which gives the overall outcomes after the primary operation for both cohorts.

Both OHS scores and EQ-5D scores were lower in CP patients before and after surgery, but the median changes in EQ-5D scores and OHS scores were similar in the 2 cohorts ().

Table 3. Comparison of the EQ-5D health scale, EQ-5D index, and Oxford hip score (OHS) in CP patients and controls, before primary hip replacement and 6 months postoperatively

Mortality

Early mortality (in the first 90 days) after hip replacement was extremely rare in the CP group, with only 1 death. The estimated cumulative mortality (Kaplan-Meier) was 0.26% (CI: 0.04–1.82) at 90 days, as compared to 0.54% (CI: 0.52–0.56) in the control group. The CP patients were younger, however, and lower longer-term mortality in this group reflected this: the cumulative mortality at 1, 3, and 5 years was 1.4% (CI: 0.6–3.3), 3.7% (CI: 2.1–6.5), and 6.9% (CI: 4.2–11.2), respectively, in the CP group, as compared to 1.6% (CI: 1.2–1.6), 5.2% (CI: 5.1–5.2), and 10% (CI: 9.8–10.1) in the controls. After stratification for the age/gender groups above, however, the difference between the CP group and the control group was not statistically significant (p = 0.1).

Discussion

We found that total hip replacement in patients with cerebral palsy is associated with a high degree of patient satisfaction, a low risk of mortality, and revision rates that were twice as high as for hip replacement in those who did not have cerebral palsy.

From the largest arthroplasty database in the world, we identified 389 hip replacements for OA in patients with CP. This number is larger than in any other series to date. We were only able to identify 1 previous study with more than 20 hip replacements: Raphael et al. (Citation2010) with 59 cases. None of the previous studies have included a comparator group.

We have combined the NJR implant survivorship with HES, ONS, and PROMS data, thereby allowing us to report 3 important domains: implant survivorship, mortality, and patient-reported outcomes (Wylde and Blom Citation2011). We believe that this approach gives a more complete and clinically relevant picture than in previous registry studies, which have reported only 1 of these domains (Hunt et al. Citation2013, Smith et al. Citation2012a and Citationb).

We found that total hip replacement for CP is uncommon, but it gives a high degree of patient satisfaction. This is in keeping with reports in the literature, where there was improvement in pain in 77–93% of cases (Buly et al. Citation1993, Weber and Cabanela 1989, Schroeder et al. Citation2010, Sanders et al. Citation2013). The EQ-5D and OHS scores showed that patients with CP were operated on when they had worse self-reported pain and function than the control patients without CP, but that they improved equally well following surgery. This indicates that thresholds for surgery may be different for patients with CP. It is now well established that preoperative patient-reported outcomes are a strong predictor of postoperative outcomes (Judge et al. Citation2013), but that multi-morbidity scores are not (Greene et al. Citation2015).

Revision rates were higher than for the non-CP patient group and the reasons for revision were different, with higher rates of revision for pain, dislocation/subluxation, aseptic loosening, and periprosthetic fracture. This is unsurprising, taking into account the complex nature of the surgery. This is unlikely to be purely an age-related phenomenon, as implant survivorship in young patients is considerably higher than that reported here for our young CP population, according to the twelvth annual report of the NJR (Utting et al. Citation2008). However, hip replacement in young patients with other systemic comorbidities affecting the musculoskeletal system can also be associated with high revision rates. Amanatullah et al. (Citation2014) reported revision rates of 35% at 5.8 years in a small series of patients with Down’s syndrome. Imbuldeniya et al. (Citation2014) reported a revision rate of 57% at 15 years in a cohort of young patients who underwent hip replacement for severe developmental dysplasia.

Patients with CP are more likely to be treated with resurfacing than those without CP. Good results using femoral osteotomy and resurfacing have previously been reported, with 89% of patients or carers expressing satisfaction with the surgery (Prosser et al. Citation2012). Hip replacement for CP is clustered around a few providers, and the highest number of cases was undertaken at a unit with particular expertise in resurfacing—which probably explains the association. The clustering of provision of surgery around a few units raises important questions regarding equity of access to care and thresholds for intervention.

Implant survivorship was highest with cemented and hybrid components, which is also true for the non-CP cohort, as reported in the National Joint Registry annual report (Citation2014).

Mortality rates for patients with CP were similar to those without CP, which indicates that surgery is safe to perform and long-term implant survivorship needs to be as good in CP patients—as their life expectancy appears to be no different 7 years after surgery.

Registries enable studies of rare conditions such as CP, and findings are generalizable when the registry includes the entire population. However, they report associations and not causation. Selection bias cannot be excluded, particularly as we have no data on the pattern or severity of CP, and thus patients with particular characteristics may have been chosen for surgery. Determination of which type of surgery gives the best outcomes would be best determined by a randomized controlled trial, but the effect size would have to be very large indeed, due to the small number of subjects available. Like all studies, registries do not have 100% case ascertainment, but we have no reason to believe that case ascertainment would differ between cases with CP and those without. A recent study of surgeons who revised metal-on-metal hip replacements suggested that these revisions may be under-reported in the NJR by approximately 16% (Sabah et al. Citation2015). The NJR’s own audits have suggested lower rates of under-reporting. If revisions are selectively under-reported compared to primary operations, then true revision rates would be higher. For example, if 10% of revisions are not reported then 5- year revision rates for CP patients would increase from 6.4% to 7.0%, and for those without CP from 2.9% to 3.2%. There is no reason to believe that there is selective under-reporting based on the diagnosis of cerebral palsy, so relative revision rates are unlikely to be affected.

In summary, hip replacement for CP appears to be safe and effective with acceptable implant revision rates. Revision rates are lowest when cemented or hybrid implants are used.

Supplementary data

Figures 3 and 4 and Tables 4 and 5 are available on the website of Acta Orthopaedica (www.acta.orthop.org), identification number 8912.

AB, LH, and GK designed the study. GK and LH analyzed the data. All the authors critically appraised the data and contributed to preparation of the manuscript. LH had full access to all the data in the study and AB had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. AB is the guarantor and asserts on behalf of the authors that the manuscript is an honest representation of the study without misrepresentations or omissions of substance.

We thank the patients and staff of all the hospitals who have contributed data to the National Joint Registry. We are grateful to the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP), the National Joint Registry Steering Committee (NJRSC), and staff at the NJR Centre for facilitating this work. The views expressed represent those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NJRSC or HQIP, who do not vouch for how the information is presented.

Role of the funding source: The Steering Committee of the National Joint Registry, which sponsored the study, had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, or writing of the final report.

Stryker and DePuy have funded other research undertaken by the University of Bristol.

- Amanatullah D F, Rachala S R, Trousdale R T, Sierra R J. Total hip replacement in patients with Down syndrome and degenerative osteoarthritis of the hip. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B(11): 1455–8.

- Bagg M R, Farber J, Miller F. Long-term follow-up of hip subluxation in cerebral palsy patients. J Pediatr Orthop 1993; 13: 32–6.

- Buly R L, Huo M, Root L, Binzer T, Wilson P D. Total hip arthroplasty in cerebral palsy. Long-term follow-up results. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1993; (296): 148–53

- Castle M E, Schneider C. Proximal femoral resection-interposition arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1978; 60-A: 1051–4.

- Egermann M, Doderlein L, Schlager E, Muller S, Braatz F. Autologous capping during resection arthroplasty of the hip in patients with cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009; 91-B (8): 1007–12.

- Greene M E, Rolfson O, Gordon M, Garellick G, Nemes S. Standard comorbidity measures do not predict patient-reported outcomes 1 year after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473(11): 3370–9.

- Hunt L P, Ben-Shlomo Y, Clark E M, Dieppe P, Judge A, MacGregor A J, Tobias J H, Vernon K, Blom A W; National Joint Registry for England, Wales and Northern Ireland. 90-day mortality after 409,096 total hip replacements for osteoarthritis, from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales: a retrospective analysis. Lancet 2013; 382(9898): 1097–104.

- Imbuldeniya A M, Walter W L, Zicat B A, Walter W K. Cementless total hip replacement without femoral osteotomy in patients with severe developmental dysplasia of the hip: minimum 15-year clinical and radiological results. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B(11): 1449–54.

- Judge A, Arden N K, Batra R N, Thomas G, Beard D, Javaid M K, Cooper C, Murray D; Exeter Primary Outcomes Study (EPOS) group. The association of patient characteristics and surgical variables on symptoms of pain and function over 5 years following primary hip-replacement surgery: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2013; 3(3). pii: e002453.

- Oskoul M, Coutinho F, Dykeman J, Jette N, Pringshelm T. An update on the prevalence of cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Chil Neurol 2013; 55(6): 509–19.

- Prosser G H, Shears E, O’Hara J N. Hip resurfacing with femoral osteotomy for painful subluxed or dislocated hips in patients with cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2012; 94-B (12): 483–7.

- Raphael B S, Dines J S, Akerman M, Root L. Long-term follow-up of total hip arthroplasty in patients with cerebral palsy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 467(7): 1845–54.

- Sanders R J M, Swierstra B A, Goosen J H M. The use of dual-mobility concept in total hip arthroplasty patients with spastic disorders. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013; 133: 1011–6.

- Sabah S A, Henckel J, Cook E, Whittaker R, Hothi H, Pappas Y, Blunn G, Skinner J A, Hart A J. Validation of primary metal-on-metal hip arthroplasties on the National Joint Registry for England, Wales and Northern Ireland using data from the London Implant Retrieval Centre: a study using the NJR dataset. Bone Joint J 2015; 97-B(1): 10–8.

- Schroeder K, Hauck C, Wiedenhofer B, Braatz F, Aldinger R. Long-term results of hip arthroplasty in ambulatory patients with cerebral palsy. Int Orthop 2010; 34(3): 335–9.

- Smith A J, Dieppe P, Vernon K, Porter M, Blom A W; National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements: analysis of data from the National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Lancet 2012a; 379(9822): 1199–204.

- Smith A J, Dieppe P, Howard P W, Blom A W; National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Failure rates of metal-on-metal hip resurfacings: analysis of data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Lancet 2012b; 380(9855): 1759–66.

- Utting M R, Raghuvanshi M, Amirfeyz R, Blom A W, Learmonth I D, Bannister G C. The Harris-Galante porous-coated, hemispherical, polyethylene-lined acetabular component in patients under 50 years of age: a 12- to 16-year review. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90(11): 1422–7.

- Wylde V, Blom A W. The failure of survivorship. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93(5): 569–70.

- Eleventh Annual Report of the National Joint Registry 2014, Hemel Hampstead.