Abstract

We report a patient who presented with takotsubo cardiomyopathy but was misdiagnosed as an anterior wall ST elevation myocardial infarction (AWMI). We illustrate how misdiagnosis led to mismanagement by initiating intravenous inotropic agents that led to further hemodynamic compromise. Subsequent withdrawal of the inotropic agents and simultaneous administration of oral metoprolol therapy led to hemodynamic and clinical improvement re-affirming the diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

Reports of patients with profound and reversible left ventricular (LV) dysfunction after sudden emotional stress have appeared in the medical literature for over two decades (Citation1–6). Although early reports of takotsubo cardiomyopathy originated from Japan, cases have been reported in Asia and the Western world (Citation1–6). Generally considered to be a benign disease, some patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy have serious adverse outcome (Citation2,Citation4,Citation6).

Case report

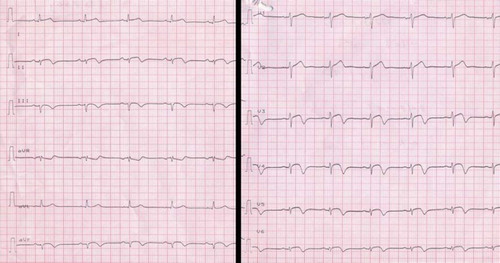

A 68-year old normotensive, non-diabetic, postmenopausal woman was admitted to the intensive care unit of a nearby hospital with acute onset of chest pain and mild headache triggered by severe emotional distress. ECG revealed ST-segment elevation in the anterior and inferior leads (). Troponin-I levels were elevated (0.2 ng/ml). The blood pressure (BP) was 92/70 mmHg with a heart rate (HR) of 100 beats per minute. Cardiac auscultation did not reveal any murmur. There were no crackles in the lung fields and the jugular venous pressure was normal. Bedside echocardiography revealed an aneurismal and akinetic apical segment with hypercontractile basal region without any significant left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) gradient. There was no evidence of mitral valve regurgitation. The estimated right ventricular systolic pressure was 30 mmHg. Right atrium, right ventricle and inferior vena cava were of normal dimensions. Based on a diagnosis of acute AWMI the patient underwent coronary angiography which revealed normal coronary arteries and severe LV dysfunction (EF of 20%) with apical ballooning (a–c). Right heart catheterization revealed a mean right atrial pressure of 6 mmHg, a peak pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 30 mmHg and mean pulmonary artery pressure of 16 mmHg. Optimal preload in the form of intravenous fluids was ensured as guided by the mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, which was 12 mmHg.

The patient was started on intravenous infusion of dopamine (10 mcg/kg/min), and dobutamine (7.5 mcg/kg/min), as well as weight adjusted unfractionated heparin and standard oral medications for acute coronary syndrome (ACS). After one hour, she developed severe headache and altered mental status. An immediate brain CT scan revealed a small ICH in the right basal ganglia (). Antiplatelet agents and intravenous heparin were withheld. Intra aortic balloon pump (IABP) support was deferred due to contra-indication for anticoagulation. Despite high doses of dopamine and dobutamine, her BP dropped to 72/50 mmHg with concomitant fall in urine output. Intravenous infusion of adrenaline was started at 2 mcg/kg/min and the patient was referred to our hospital for further management.

Upon re-evaluation at our center, we suspected that the patient had been misdiagnosed and that the most likely diagnosis was takotsubo cardiomyopathy. There was no murmur on cardiac auscultation and bed side 2D echo color Doppler examination revealed no LVOT obstruction or SAM. Subsequently, we initiated a gradual withdrawal of inotropic agents which led, over the ensuing 12 h, to significant improvement in BP (106/70 mmHg), reaffirming our diagnosis. At that point, oral metoprolol was started at 50 mg orally b.i.d. Inotropic agents were discontinued after 36 h. Serial echocardiograms over the ensuing 2 weeks revealed improved contractility and diminished apical ballooning. Patient continued to improve neurologically and hemodynamically and was eventually discharged at day 15 with a BP of 118/78 mmHg, a HR of 74 beats per minute, and a LV ejection fraction (EF) of 50%. Follow-up examination four weeks after discharge revealed normal clinical, cardiac and neurological examination and a normal LVEF of 60%.

Discussion

The term takotsubo cardiomyopathy describes a clinical entity of acute and rapid LV dysfunction, usually reversible, precipitated by emotional or physiological stress. This condition mimics acute anterior wall myocardial infarction clinically, electrocardiographically and echocardiographically and is characterized by a distinctive LV shape resembling a ‘takotsubo’ (a Japanese pot for octopus fishing) with a ballooned appearance of the apical region and a hyperkinetic base (Citation1–3). Proposed mechanisms of the development of apical ballooning include multi-vessel coronary spasm, impaired cardiac microvascular function, adrenoreceptor hypersensitivity and regional differences in receptor density (Citation1–6). High catecholamine levels subdivide the LV into two functionally different chambers with a marked increase in wall stress in the distal apical chamber.

Although the precipitating factor for takotsubo cardiomyopathy in this case may well be emotional distress we can not rule out the possibility of subclinical ICH as a precipitating factor (Citation4). It is clear, in hindsight, that takotsubo cardiomyopathy was misdiagnosed as AWMI as the patent LAD was interpreted as a ‘recanalized’ occlusion! Misdiagnosis led to mismanagement by initiating intravenous heparin and intravenous inotropic agents, which led to further hemodynamic deterioration and worsening of the ICH. The favorable hemodynamic and clinical response to withdrawal of inotropic support is an important clinical caveat that can also be observed in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. This case illustrates that takotsubo cardiomyopathy should always be on the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with what appears to be AWMI. A finding of patent LAD on coronary angiography and LV apex ballooning should trigger supportive management that include intra aortic balloon pump for hemodynamic instability, rather than stepping up intravenous inotropes. Ruling out ICH in patients with headache or altered mental status in such clinical presentations is of prime importance.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Tsuchihaghi K, Ueshima K, Uchida T, . Transient left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis: A novel heart syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;38:11–8.

- Pilgrim TM, Wyss TR. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: A systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2008;124:283–92.

- Kyuma M, Tsuchihashi K, Shinshi, Y, . Effect of intravenous propanolol on left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis (ampulla cardiomyopathy)—three cases. Circ J. 2002;66:1181–4.

- Rahini AR, Katayama M, Mills J. Cerebral hemorrhage: Precipi-tating event for a takotsubo-like cardiomyopathy? Clin Cardiol. 2008;31:6:275–80.

- Dandel M, Lehmkuhi HB, Schmidt G, . Striking observations during emergency catecholamine treatment of cardiac syncope in a patient with initially unrecognized takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2009;73:1543–6.

- Abe Y, Tamura A, Kadota J. Prolonged cardiogenic shock caused by a high-dose intravenous administration of dopamine in a patient with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2010;141:e1–e3.