Abstract

Coronary artery embolus is a rare and potentially under- recognised cause of acute myocardial infarction. We describe the case of an 80-year-old woman presenting with an acute coronary syndrome secondary to coronary artery embolus associated with atrial fibrillation, which was successfully treated with the use of a thrombectomy aspiration catheter.

Introduction

Acute coronary syndromes consisting of chest pain, electrocardiographic changes and cardiac enzyme elevations have diverse aetiologies. Clinicians treating patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes need to be aware that not all acute coronary syndromes are due to thrombotic occlusion of coronary arteries following acute plaque rupture. Here, we describe the case of an 80-year-old woman presenting with an acute coronary syndrome due to a coronary artery embolus most likely associated with recent onset paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. This was successfully managed with the use of an aspiration thrombectomy catheter.

Case report

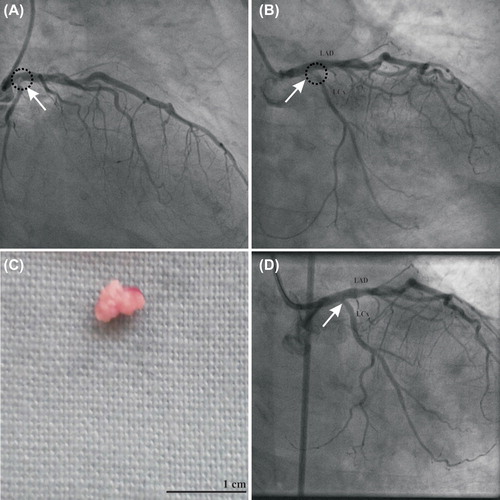

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, dyslipidaemia and previously treated localised breast cancer, presented to a regional hospital with central chest heaviness. Electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation (AF) with a rapid ventricular response rate and ST-segment depression in the inferior and antero-lateral leads (). High sensitivity troponin T was elevated at 1391 (normal < 14 ng/l). She was treated with anti-platelet agents, beta-blockade, a statin and anti-coagulation with low molecular weight heparin. On transfer to our institution, she had reverted to sinus rhythm. Coronary angiography demonstrated a hazy abnormality in the distal left main trunk, extending into the ostium of the left circumflex artery (, ). The remainder of the left circumflex artery was disease free. The left anterior descending and right coronary arteries were free of atheromatous disease. Left ventriculogram demonstrated normal left ventricular systolic function.

Figure 1. Electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response rate and ST-segment depression in leads II, III, aVF, and V1 to V5. Scale: 25 mm/s; 10 mm/mV.

Figure 2. Coronary angiogram demonstrated a hazy filling defect (arrow) at the bifurcation of the distal left main trunk and left circumflex artery, depicted in right anterior oblique caudal (A) and left anterior oblique caudal projections (B). A fibrous mass was aspirated by a thrombectomy catheter (C), with resolution of the filling defect on coronary angiogram (arrow, D). LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCx, left circumflex artery.

Manual aspiration via a 7 French thrombectomy catheter (Export catheter; Medtronic, MA, USA) successfully retrieved a pink fibrous mass from the bifurcation of the distal left main trunk and left circumflex artery (). Coronary angiogram post aspiration demonstrated no remaining obstructive lesions in the left main trunk and left circumflex artery (). Therefore, no angioplasty or stenting was undertaken. Given the new diagnosis of paroxysmal AF, and the appearance of the hazy abnormality in the distal left main trunk, we had a high suspicion that the culprit may be a coronary artery embolus related to AF. The appearance of the retrieved mass was consistent with an embolus. The following day, the patient had a further episode of asymptomatic AF. Transthoracic echocardiography showed good left ventricular function and no evidence of an intra-cardiac mass or shunt. As part of management for AF, our patient was anticoagulated with warfarin. She was discharged on day four of admission, and has remained clinically well.

Discussion

Acute myocardial infarction due to coronary artery embolus is rare. Sources of coronary artery embolus include vegetations from infective endocarditis, and intra-cardiac thrombi (Citation1, Citation2). Primary angioplasty and stenting, with aggressive anticoagulation is one management strategy, however, distal embolisation of the embolus during angioplasty is a feared complication (Citation3). This can be a risky management strategy, as illustrated by a previous case report of a 64-year-old man who presented with an acute anterior myocardial infarction due to coronary artery embolus associated with atrial fibrillation (Citation3). Despite rescue angioplasty after failed thrombolysis achieving satisfactory angiographic result, the patient died from intracranial haemorrhage due to aggressive anticoagulation (Citation3). Thrombus aspiration has been shown to result in better reperfusion and clinical outcomes than conventional percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (Citation4). However, the application of thrombectomy aspiration catheter in coronary artery embolus due to AF has been reported in only one case previously (Citation5). A 72-year-old man with an inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction was treated with an aspiration catheter, retrieving a large embolus from the right coronary artery (Citation5). Our case further demonstrates the effectiveness and safety of thrombectomy catheter aspiration for acute myocardial infarctions due to coronary artery emboli. Our case also serves to highlight the importance of considering coronary artery embolus as a potential cause of acute coronary syndrome, when patients with otherwise normal coronary arteries are found to have localised filling defects on coronary angiography.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Taniike M, Nishino M, Egami Y, Kondo I, Shutta R, Tanaka K, et al. Acute myocardial infarction caused by a septic coronary embolism diagnosed and treated with a thrombectomy catheter. Heart 2005;91:e34.

- Hernandez F, Pombo M, Dalmau R, Andreu J, Alonso M, Albarran A, et al. Acute coronary embolism: Angiographic diagnosis and treatment with primary angioplasty. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;55:491–4.

- Van de Walle S, Dujardin K. A case of coronary embolism in a patient with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation receiving tamoxifen. Int J Cardiol. 2007;123:e18–20.

- Svilaas T, Vlaar PJ, van der Horst IC, Diercks G FH, de Smet B JGL, van den Heuvel , et al. Thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2008;358: 557–67.

- Sakai K, Inoue K, Nobuyoshi M. Aspiration thrombectomy of a massive thrombotic embolus in acute myocardial infarction caused by coronary embolism. Int Heart J. 2007;48:387–92.