Abstract

Presented is the case report of a patient noted to have gross distortion of the internal cervical canal during her attempt at embryo transfer following an in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF-ICSI) procedure. Multiple attempts at cervical dilation were unsuccessful and the patient was ultimately treated by transmyometrial embryo transfer also known as the Towako method. She successfully achieved a singleton pregnancy and delivered at 41 weeks by primary cesarean section because of arrest of cervical dilation. Transmyometrial embryo transfer represents a viable option for patients with cervical stenosis refractory to conventional methods of navigation or severe anatomical distortion of the internal cervical canal.

Introduction

Pregnancy success following in vitro fertilization (IVF) is known to correlate with the ease of embryo transfer (ET) [Brown et al. Citation2010; Mains and Van Voorhis Citation2010]. Several conditions including cervical stenosis and severe anatomical distortion of the cervical canal can make ET difficult. Cervical stenosis is often a result of scar tissue formed after cervical surgery, trauma, or radiation. It may also be the result of encroaching cervical tumors. Cervical stenosis typically presents with scant, painful menses, hematometra, or may be diagnosed at the time of endometrial biopsy or hysteroscopy. In patients suspected of cervical stenosis undergoing IVF and ET, mechanical cervical dilation at the time of oocyte retrieval is often performed and may result in an easier ET but does not always yield good pregnancy rates [Groutz et al. Citation1997a; Groutz et al. Citation1997b].

Severe anatomical distortion of the cervical canal may also be a result of congenital malformation and is often discovered during diagnostic testing to define the pelvic anatomy, such as a sonohysterogram or hysterosalpingogram. Finally, an inability to pass small catheters at the time of an intrauterine insemination or ET may also alert physicians to underlying pathology in the absence of gross anatomic abnormality. Mechanical cervical dilation may not be helpful in navigating a cervical canal with severe anatomic distortion and is often accompanied by uterine perforation or the creation of false passages.

We report a case of a patient presenting with primary infertility and an unusually difficult transcervical ET during her first IVF-ICSI treatment cycle. Mechanical cervical dilation was unsuccessful and the pregnancy was ultimately achieved by transmyometrial embryo transfer (TMET).

Case Report

A 34 year-old nulligravida presented to Columbia University with infertility for three years. Her gynecological history was otherwise unremarkable. She had no history of oligomenorrhea and reported normal monthly menses without dysmenorrhea. She denied having uterine myomas, ovarian cysts, pelvic infections, abnormal pap smears, or previous pelvic surgeries. She had no history of cervical lesions or procedures including loop electrosurgical excision procedure, cone biopsy, or cryosurgery. There was no history of hematometra. Her medical history was noncontributory and she denied smoking, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. Baseline transvaginal ultrasound revealed an anteverted uterus measuring 6.5 × 4.2 × 3.0 cm with a small subserosal high fundal myoma 0.9 × 0.8 × 0.8 cm noted in the anterior wall, a symmetric endometrium, and a normal cervix with endocervical stripe measuring 2.5 cm in length. Initial work-up, including a hysterosalpingogram (HSG), ovarian reserve testing, and screening for sexually transmitted infections was unremarkable. The patient’s HSG, which was done at an outside institution, was reported as normal with no mention of difficulty cannulating the external cervical os with a 7 French H/S catheter (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, CT, USA). Thus, we did not perform a sonohysterogram prior to initiating fertility treatment or see the need to perform a mock ET.

Her partner was a 45 year-old male with unremarkable medical history without proven fertility and reportedly normal sexual function. His initial semen analysis revealed a normal semen volume and concentration of sperm, but sperm motility of 24% and 9% normal forms, with World Health Organization (WHO) [Citation1999] cut-off reference values of 50% motility and 15% normal forms. Repeat semen analysis revealed 21% motility, 15% progressive motility, and 0% normal morphology, with WHO 2010 cut-off reference values of 40% motility, 32% progressive motility, and 4% normal forms [Cooper et al. Citation2010]. The couple was counseled regarding possible problems of fertilization related to the male gametes and elected to undergo IVF-ICSI to maximize pregnancy potential.

The patient underwent pituitary down regulation with GnRH agonist followed by 10 days of ovarian stimulation with gonadotropins. Oocyte maturation was achieved with an injection of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and eighteen oocytes were retrieved by transvaginal ultrasound guided needle aspiration approximately 35 hours later. Embryos were created by ICSI and were cultured to the blastocyst stage. Three ‘high quality’ grade blastocysts were available for transfer and cryopreservation. With seemingly optimal ET conditions of abdominal ultrasound guidance with clear visualization and a full bladder, two highly experienced physicians (more than 20 years of ET experience for each physician) attempted to navigate the patient’s cervical canal using a Wallace embryo replacement catheter with stylet (Smiths Medical, Norwell, MA, USA) and an Echosight Patton Embryo Transfer Catheter with a coaxial wire (also known as J-wire catheter) (Cook Ob/Gyn, Bloomington, IN, USA), but were unable to introduce a catheter beyond her external os. Additional attempts at catheter placement using a cervical tenaculum and retrograde bladder distention were also unsuccessful. The decision was therefore made to cryopreserve all three blastocysts and perform further evaluation of the cervical canal before attempting another ET.

Mechanical cervical catheterization or dilation under conscious sedation in the office was attempted approximately one month later, but again, the attending physicians were unable to navigate the patient’s cervical canal. The patient was then taken to the operating room for cervical dilation and hysteroscopy under ultrasound and laparoscopic guidance with pre-procedure misoprostol (Cytotec - G.D. Searle & Company, Chicago, IL, USA). Examination under anesthesia revealed a normal appearing vagina, small, firm cervix, with a pinpoint external os and normal sized anteverted uterus. Diagnostic laparoscopy confirmed an anteflexed and left deviated uterus, normal fallopian tubes, and several small 1 mm endometriotic implants on the right infundibulopelvic ligament.

Despite optimal visualization with ultrasound and adequate cervical preparation, the endocervical canal was again unable to be dilated. During the case, cervical dilation was attempted with pediatric dilators and Hank dilators but the rigid 5 mm hysteroscope was unable to enter the cervical canal. A false cervical passage was created and the procedure was aborted. The patient was again taken to the operating room for another attempt at cervical evaluation and dilation approximately one month later. During this second procedure, endocervical tissue thought to be causing a stricture was visualized and removed, the cervical canal was navigated, and the endometrial cavity visualized. Pathological analysis of the biopsied stricture returned, ‘fragments of negative endocervix’ and ‘lower uterine segment’.

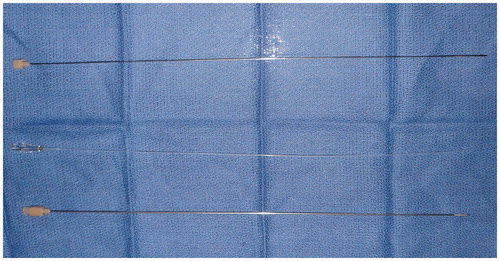

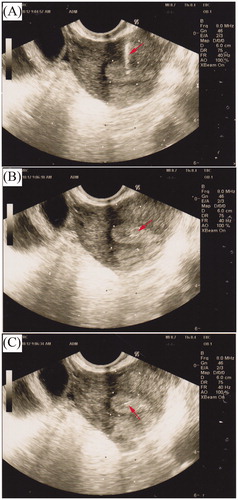

Given the anatomical distortion of this patient’s cervical canal making the canal so convoluted as to not allow conventional instruments to pass, the decision was made to proceed with cryopreserved ET using the Towako method as described by Kato et al. [Citation1993], with the Transmyometrial Embryo Transfer Set (Cook Ob/Gyn, Bloomington, IN, USA) (). After routine preparation for cryopreserved ET using established protocols [Glujovsky et al. Citation2010], the patient presented for a scheduled TMET. She was brought to the operating room with an empty bladder and was placed in dorsal lithotomy position where TMET was performed with monitored anesthesia care (MAC) using propofol and fentanyl for sedation and transvaginal ultrasound guidance of the needle into the endometrial cavity, as previously described [Pasqualini and Quintans Citation2002]. In brief, a 19-gauge needle fitted with a stylet was inserted into the anterior fornix, advanced through the upper vaginal wall, anterior myometrium, anterior endometrial layer, and into the uterine cavity. The needle was then pulled back until the tip was visualized clearly within the middle of the endometrial stripe. Intracavitary placement was confirmed by injection of a small volume of culture media. The inner catheter, loaded with the three thawed blastocyst stage embryos suspended in culture media, was threaded through the outer catheter, and the embryos were deposited within the uterine cavity [Pasqualini and Quintans Citation2002] (). Although our standard of care is to transfer no more than two blastocyst stage embryos, this couple requested the transfer of all three embryos understanding that this placed her at enhanced risk for multiple gestation. After careful consideration this request was granted.

Figure 1. The Transmyometrial Embryo Transfer Catheter Set (Cook Medical, Spencer, IN, USA). From top to bottom: stylet, 2 French polyethylene embryo transfer catheter, 19-gauge echotipped needle.

Figure 2. Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) during transmyometrial embryo transfer. A) catheter placement, (B) during embryo transfer, and (C) post embryo transfer.

The first attempt of TMET achieved a chemical pregnancy that ultimately failed. She then underwent a second attempt at IVF-ICSI with the intentional plan for TMET. As a result of this second attempt only three viable appearing cleavage stage embryos were available for ET by the third culture day. The patient was given the option of proceeding with blastocyst culture or having the earlier stage embryos transferred by TMET. She elected to have all three cleavage stage embryos placed. Therefore, the three 8-cell embryos were transferred by TMET using MAC anesthesia, resulting in a singleton intrauterine pregnancy.

Her pregnancy was uncomplicated and she presented for a post-dates induction of labor at 41+ weeks gestational age. At presentation for induction, her cervix was described as <1 cm dilated and an intra-cervical balloon was successfully placed. She was transitioned to intravenous oxytocin and spontaneously ruptured her membranes at 4 cm dilation. She had an arrest of cervical dilation at 9 cm and consequently underwent a low-transverse cesarean section and delivered a healthy male infant weighing 3400 g.

Discussion

Embryo transfer is one of the most critical steps in assisted reproduction. Transcervical intrauterine transfer under ultrasound guidance is the current standard of care and visualization has been shown to improve pregnancy outcomes by facilitating catheter insertion and placement, providing an accurate assessment of catheter position and reducing uterine contractility that can be caused by catheter contact with the uterine fundus [Brown et al. Citation2010; Lindheim et al. Citation1999; Mains and Van Voorhis Citation2010]. Other techniques, such as zygote intra-fallopian transfer (ZIFT), pronuclear stage transfer, and embryo intra-fallopian transfer (EIFT) are largely historical, but are still used occasionally today under special circumstances. In patients where uterine access via the transcervical technique is not possible or has been extremely difficult, TMET represents a viable alternative.

Transmyometrial embryo transfer

Parsons et al. performed the first TMET using a spinal needle [Brown et al. Citation2010; Parsons et al. Citation1987], however, Kato et al. [Citation1993] coined the term ‘the Towako method’ as described in their series of 104 women (mean age 32 years, average 6 years of infertility with tubal factor) who had failed at least two prior IVF-ET attempts because of abnormal cervical conditions causing difficulty with the ET. In 28 cases, IVF- ET was carried out in a fresh cycle and in 24 cases, frozen-thawed embryos were transferred in a hormone replacement cycle. At the time of ET, under transvaginal ultrasound guidance, a 250 mm length 18-gauge Hakko needle (Hakko Co., Tokyo, Japan) was inserted transmyometrially between the upper margin of the cervix and the lower edge of the bladder. A polyethylene catheter was introduced when the tip of the Hakko needle reached the outer layer of the endometrium at the level of the fundus. The embryos, in a total volume of 30 µL, were loaded at the tip of the catheter and transferred by gentle injection. On average, two embryos were transferred without anesthesia and all patients received 25-mg/day intramuscular progesterone starting two days after ET. The clinical pregnancy rate was 36.5%, similar to clinical pregnancy rates after transcervical ET [Kato et al. Citation1993].

Since 1993, there have been only a few case reports in various countries reporting use of the Towako method in patients with cervical atresia or stenosis in which transcervical ET was not possible [Jamal et al. Citation2009; Pasqualini and Quintans Citation2002; Xu et al. Citation2009]. In 1999, Anttila et al. described a patient with congenital cervical dysgenesis who achieved a successful pregnancy after IVF and TMET at age 32 years after failure to create a neocervix. This patient was delivered by cesarean section at 32 weeks for preeclampsia and breech presentation [Anttila et al. Citation1999]. Jamal et al. [2009] described a successful intrauterine pregnancy after IVF-TMET in a 33 year-old patient, status-post radical trachelectomy for stage IA2 cervical adenocarcinoma. This patient was delivered by elective cesarean section at 38 weeks gestation [Jamal et al. Citation2009]. In 2009, Xu et al. reported a triplet pregnancy after IVF-TMET followed by multifetal reduction and successful twin delivery of a woman with congenital cervical atresia [Xu et al. Citation2009]. Lin et al. [Citation2010] reported a clinical pregnancy that ended in a missed abortion in a patient with complete cervical atresia and vaginal dysgenesis who underwent IVF followed by transmyometrial blastocyst stage ET. Muñoz et al. [Citation2014] recently described a successful twin delivery following TMET in a patient with a false uterine cavity. To the best of our knowledge, the current case is the first reported case in the United States that demonstrates the successful use of the Towako method of ET and the only case of pregnancy occurring in two consecutive attempts at TMET. Furthermore, the procedure was carried out with equipment readily available in assisted reproduction centers, making it readily accessible to most American practitioners.

As with transcervical ET, the success of TMET might be limited by junctional zone contractions [Biervliet et al. Citation2002] which likely occurs following needle puncture. Junctional zone contractions, often stimulated by difficult transcervical ETs or the use of a tenaculum, can lead to embryo expulsion thus reducing the success of IVF. Biervliet et al. [Citation2002] offered TMET to 10 patients in whom a difficult transcervical ET was anticipated. Uterine activity was assessed with transvaginal ultrasound for 2 minutes prior to the transfer and 3 minutes after the transfer. Minimal junctional zone activity was seen prior to TMET but there was a statistically significant increase in contractions after TMET compared to transcervical catheter placement [Biervliet et al. Citation2002].

Other potential complications of TMET include bleeding, injury to adjacent organs, infection, and pain, although to date these theoretical risks have not been reported in the literature [Sharif et al. Citation1996]. Other complications include ectopic pregnancy, missed abortion, and multiple gestations [Lesny et al. Citation1999; Lin et al. Citation2010; Xu et al. Citation2009], but there is insufficient evidence to directly link these events specifically to TMET. In the case we describe, TMET was carried out twice with MAC anesthesia. The patient tolerated the procedure well. Post-procedure, she did not report any uterine cramping and there were no complications.

Conclusion

The case we present resulted in pregnancy after each of two attempts of TMET. Our patient likely has a congenital malformation resulting in a tortuous cervical canal that could not be navigated with conventional transcervical ET catheters and techniques. Our success paired with the relative ease of this procedure in a center that does not routinely perform TMET, suggests that most other programs performing assisted reproduction may adopt this procedure as necessary for select patients. Furthermore, the planned use of TMET may prevent delays in the treatment of patients with a history of difficult ET, regardless of etiology, by bypassing multiple failed transcervical transfers and difficult cervical dilations commonly experienced by these patients [Sharif et al. Citation1996]. Other centers could potentially carry out TMET as the skills required, specifically transvaginal ultrasonography of the uterus and ultrasound-guided needle puncture procedures, are already familiar to most reproductive endocrinologists [Sharif et al. Citation1996]. In vitro fertilization with TMET can and should be an option for patients in whom transcervical ET with conventional instruments and techniques is extremely challenging or found to be impossible.

Declaration of interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Wrote and edited the manuscript: CSS-P, DHK; Performed the TMET procedures and edited the manuscript: MVS; Organized the patient’s care, and wrote and edited the manuscript: NCD.

| Abbreviations | ||

| IVF-ICSI | = | in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection |

| ET | = | embryo transfer |

| TMET | = | transmyometrial embryo transfer |

| HSG | = | hysterosalpingogram |

| hCG | = | human chorionic gonadotropin |

| MAC | = | monitored anesthesia care |

| ZIFT | = | zygote intra-fallopian transfer |

| EIFT | = | embryo intra-fallopian transfer |

References

- Anttila, L., Penttilä, T.A. and Suikkari, A.M. (1999) Successful pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization and transmyometrial embryo transfer in a patient with congenital atresia of cervix: Case report. Hum Reprod 14:1647–9

- Biervliet, F.P., Lesny, P., Maguiness, S.D., Robinson, J. and Killick, S.R. (2002) Transmyometrial embryo transfer and junctional zone contractions. Hum Reprod 17:347–50

- Brown, J., Buckingham, K., Abou-Setta, A.M. and Buckett, W. (2010) Ultrasound versus ‘clinical touch' for catheter guidance during embryo transfer in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Issue 1. Art. No.: CD006107. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD006107.pub3

- Cooper, T.G., Noonan, E., von Eckardstein, S., Auger, J., Baker, H.W., Behre, H.M., et al. (2010) World Health Organization reference values for human semen characteristics. Hum Reprod Update 16:231–45

- Glujovsky, D., Pesce, R., Fiszbajn, G., Sueldo, C., Hart, R.J. and Ciapponi, A. (2010) Endometrial preparation for women undergoing embryo transfer with frozen embryos or embryos derived from donor oocytes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Issue 1. Art. No.: CD006359. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006359.pub2

- Groutz, A., Lessing, J.B., Wolf, Y., Azem, F., Yovel, I. and Amit, A. (1997a) Comparison of transmyometrial and transcervical embryo transfer in patients with previously failed in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer cycles and/or cervical stenosis. Fertil Steril 67:1073–6

- Groutz, A., Lessing, J.B., Wolf, Y., Yovel, I., Azem, F. and Amit, A. (1997b) Cervical dilatation during ovum pick-up in patients with cervical stenosis: Effect on pregnancy outcome in an in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer program. Fertil Steril 67:909–11

- Jamal, W., Phillips, S.J., Hemmings, R., Lapensée, L., Couturier, B., Bissonnette, F., et al. (2009) Successful pregnancy following novel IVF protocol and transmyometrial embryo transfer after radical vaginal trachelectomy. Reprod Biomed Online 18:700–3

- Kato, O., Takatsuka, R. and Asch, R.H. (1993) Transvaginal-transmyometrial embryo transfer: The Towako method; experiences of 104 cases. Fertil Steril 59:51–3

- Lesny, P., Killick, S.R., Robinson, J., Titterington, J. and Maguiness, S.D. (1999) Ectopic pregnancy after transmyometrial embryo transfer: Case report. Fertil Steril 72:357–9

- Lin, T.K., Lin, Y.R., Lai, T.H., Lee, F.K., Su, J.T. and Lo, H.C. (2010) Transmyometrial blastocyst transfer in a patient with congenital cervical atresia. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 49:366–9

- Lindheim, S.R., Cohen, M.A. and Sauer, M.V. (1999) Ultrasound guided embryo transfer significantly improves pregnancy rates in women undergoing oocyte donation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 66:281–4

- Mains, L. and Van Voorhis, B.J. (2010) Optimizing the technique of embryo transfer. Fertil Steril 94:785–90

- Muñoz, M., Galindo, N., Perez-Cano, I., Cruz, M. and Garcia-Velasco, J.A. (2014) Successful twin delivery following transmyometrial embryo transfer in a patient with a false uterine cavity. Reprod Biomed Online 28:137–40

- Parsons, J.H., Bolton, V.N., Wilson, L. and Campbell, S. (1987) Pregnancies following in vitro fertilization and ultrasound-directed surgical embryo transfer by perurethral and transvaginal techniques. Fertil Steril 48:691–3

- Pasqualini, R.S. and Quintans, C.J. (2002) Clinical practice of embryo transfer. Reprod Biomed Online 4:83–92

- Sharif, K., Afnan, M., Lenton, W., Bilalis, D., Hunjan, M. and Khalaf, Y. (1996) Transmyometrial embryo transfer after difficult immediate mock transcervical transfer. Fertil Steril 65:1071–4

- Sharif, K. and Kato, O. (1998) Technique of transmyometrial embryo transfer. Middle East Fertility Society Journal 3:124–9

- WHO (1999) World Health Organization laboratory manual for the examination of human semen and sperm-cervical mucus interaction. 4th ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- Xu, C., Xu, J., Gao, H. and Huang, H. (2009) Triplet pregnancy and successful twin delivery in a patient with congenital cervical atresia who underwent transmyometrial embryo transfer and multifetal pregnancy reduction. Fertil Steril 91:1958.e1951–3