Abstract

Infertile patients presenting with poor semen concentration, motility, and morphology have significantly higher levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In this cross-sectional study, our goal was to: 1) determine how semen parameters such as concentration, motility, morphology, as well as ROS are altered in oligozoospermic men alone and those in combination with poor sperm concentration, motility, morphology, and compare these with three control groups; unproven donors, donors with proven fertility <2 years, and proven donors with fertility established >2 years; 2) establish the cutoff, sensitivity, specificity for ROS, and see how it compared in the three donor groups compared to the patient groups, and 3) establish the reference range for the various semen parameters in these three donor groups compared to the oligozoospermic group by generating receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for each parameter. Fifty-six donors and 101 infertile men were included in this study. The patient group included: oligozoospermia: n = 16; oligoasthenozoospermia (OA): n = 12; oligoteratozoospermia (OT): n = 19; oligoasthenoteratozoospermia (OAT): n = 54. The patient group was compared with the three donor groups. Proven donors who had established a pregnancy in the past or recently (<2 years) had significantly improved semen motility and morphology compared to the OAT and OT groups (p < 0.001). In the OAT group, normal morphology was positively correlated with concentration and negatively with levels of ROS. Compared to the three donor groups, oligozoospermic patients in the OAT, OT, and OA groups had significantly elevated ROS levels. The cutoff for ROS in the proven donors < 2 years was significantly lower with a higher sensitivity and specificity compared to the unproven donors and donors who had not established a recent pregnancy. These results indicate a positive association between semen parameters and ROS suggesting a common underlying mechanism in these infertile patient groups.

Introduction

Infertility is a condition affecting 15% of the world’s population [Rowe et al. Citation2000; The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (2012)]. It is a multi-factorial phenomenon, with both males and females implicated in the cause. Males contribute to 45% to 50% of these infertility cases [Rowe et al. Citation2000]. The concept of infertility has important implications, both medically and psychologically, for a multitude of couples. If unresolved, these couples may face childlessness for the remainder of their lives. This is an undesirable outcome for any individual hoping for offspring.

The male factor is considered to be involved when one or more semen parameters are abnormal [Cavallini Citation2006]. These semen parameters include sperm concentration, motility, and/or morphology. Abnormalities in these three areas are termed as oligozoospermia; currently defined as less than 15 × 106 sperm/mL of seminal ejaculate, asthenozoospermia as less than 40% motility, and teratozoospermia as less than 4% normal forms [Cooper et al. Citation2010; WHO Citation2010]. These abnormal semen parameters often combine, resulting in a condition known as oligoasthenoteratozoospermia (OAT) syndrome [Dohle et al. Citation2005].

Abnormalities in sperm count have been shown as the most common of abnormalities and are typically a major contributory factor in men classified as infertile [Milardi et al. Citation2012; Pant Citation2013]. Abnormalities in semen parameters can occur due to age, chromosomal abnormalities, hormonal imbalance, or infection, and are often idiopathic [Rowe et al. Citation2000]. In the past, studies have attempted to delineate a relationship between male infertility and sperm quality as well as semen parameter abnormalities. Recently, studies have also drawn relationships between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and male infertility [Agarwal et al. Citation2008; Desai et al. Citation2009; Mahfouz et al. Citation2010].

Both oligozoospermia and the presence of ROS individually have a strong relationship with infertility [Guz et al. Citation2013; Kullisaar et al. Citation2013; Mahanta et al. Citation2012; Milardi et al. Citation2012]. A few studies have recently performed small comparisons between oligozoospermic and non-oligozoospermic groups in terms of oxidative stress [Kullisaar et al. Citation2013]. These studies showed a negative correlation between NO and H2O2 and sperm count and motility. Furthermore, H2O2 was shown to be increased in groups of oligozoospermia [Kullisaar et al. Citation2013]. This indicates an interesting relationship between the two. While the exact mechanism of oligozoospermia is not yet well understood, a previous study has linked OAT and azoospermia to lymphocyte sex chromosome aneuploidy, suggesting potential defects in cell division in these men [De Palma et al. Citation2005].

Our goal was to examine the underlying mechanism in infertile patients with low sperm count, motility, and morphology and compare them with healthy men that have unproven fertility or have initiated a pregnancy in the past or had a recent pregnancy (<2 years). The primary goal was to examine how oligozoospermic subgroups compare with the three control groups, i.e., healthy male volunteers who are normal based only on the semen characteristics and who have not been evaluated for infertility as well as those who are of proven fertility. Furthermore, we were also interested to see how these parameters compare to the three control groups who had established a pregnancy in the past or a recent pregnancy (<2 years). The secondary goal was to examine the levels of ROS produced in the infertile men who were oligozoospermic or a combination of OA, OT, or OAT and establish the cut-off, sensitivity, and specificity and establish the role of oxidative stress in these men. Lastly, we wanted to establish the reference range for the various semen parameters in these three donor groups compared to the oligozoospermic group by generating receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for each parameter. This is important to see if these values are different than those established by the new WHO [Citation2010] guidelines.

Results

Primary Diagnoses

A total of 139 patients had their primary diagnoses recorded. Of these 139 subjects, 113 (81%) had primary infertility and 26 (19%) had secondary infertility. A total of 38 patients were excluded due to incomplete semen analysis results or inadequate semen sample for measurement of ROS. In the subgroup of patients with primary infertility, we noted primary diagnoses of varicocele, XXY chromosomal abnormality, infection, history of testicular torsion or cryptorchidism, epididymal cysts, positive cystic fibrosis screen, low testosterone, low libido, and erectile dysfunction (ED). In the subgroup of patients with secondary infertility, patients had primary diagnoses of varicocele, ED, low libido, vas deferens defect, and history of infection with gonorrhea or Chlamydia. Due to the low number of patients, no sub-group analysis of the results was conducted.

Semen parameters

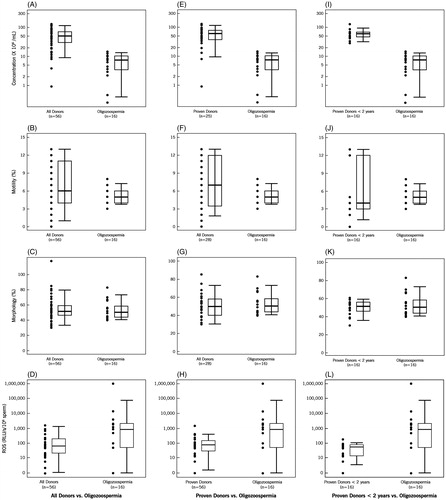

The distribution of different semen parameters among the three donor and four patient groups is shown in . In the proven fertility donors and proven donors <2 years fertility, ejaculate volume was significantly reduced in the OAT, OT, and OA patients. Compared to the three donor groups, concentration and morphology was significantly lower in the four patient groups (p < 0.001). Motility was significantly reduced in the OA and OAT groups compared to the three donor groups (p < 0.001).

Table 1. Values for volume, concentration, motility, leukocytes, normal morphology, and ROS in the three donor groups when compared to the patient groups.

The distribution of the four parameters, i.e., concentration, motility, morphology and ROS in the three donor groups compared to the oligozoospermic group is also demonstrated by box plots for all donors vs. oligozoospermic group (); proven donors vs. oligozoospermic group (E–H), and proven donors vs. oligozoospermic group (I –L). As seen in , sperm concentration and morphology were significantly higher in the three donor groups compared to the oligozoospermic group.

Figure 1. Box plot for semen parameters of donors vs. oligozoospermic patients. Box plots comparing sperm concentration, morphology, motility, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in: A–C):all donors vs. oligozoospermic patient group; E–H) proven donors vs. oligozoospermic patient group, and, I–L) proven donors <2 years of fertility vs. oligozoospermic patient group. Each box plot shows the width and the whiskers. The width of the box is proportional to the size of the group. The bottom and the top of the box represent the 25th and 75th percentile. The band in the box is the median. The whiskers represent the standard deviation. These box plots show that concentration, motility, morphology, and ROS vary between groups of donors and patients.

ROS levels in donor and patient groups

The lowest amount of ROS levels median (25th, 75th percentile) were seen in the proven donors <2 years of fertility groups [58.8(14.2, 79.2)]. Reactive oxygen species levels were higher in the oligozoospermia group 855.7 (49.8, 2030.3) compared with the all donors group [64.8(21.1, 198.2)] (p < 0.06). Similarly the ROS levels were significantly higher in the OAT group [883.8 (199.3, 3778)] (p < 0.001) and OT group [600.0 (111.8, 3573.6)] (p < 0.029). The highest levels were seen in the OA group [3253.6 (544.2, 10433.6)] (p < 0.001) (). The same trend was seen when ROS levels were compared in the proven donors and proven donors <2 years. As seen in , levels of ROS were significantly lower in the three donor groups compared to the oligozoospermic group.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for semen parameters

Receiver operating characteristic curves were generated for volume, concentration, motility, and morphology between each donor group and the four patient groups as shown in . Sensitivity, specificity, cutoff, and area under curve (AUC) were calculated for each semen parameter. Among the all donors group, the cutoff value for ejaculate volume varied significantly from 2.7 mL in the OA group to 5.2 mL in the OAT group. Sensitivity varied from 66.7% in the OA group to 94% in the OAT group. Area under curve varied from 0.473 in the oligozoospermic group to 0.5489 in the OA group. Concentration showed a cutoff from 13.9 × 106/mL in the OT group to 16.5 × 106/mL in the oligozoospermic group. With 100% sensitivity and >87% specificity. Motility ranged from 40% in the OAT group to 45% in the oligozoospermic and the OT group. Similarly, percent normal morphology ranged from 2.5% in the OAT to 8.5% in the oligozoospermic group. When the proven donors were compared, the cutoff for ejaculate volume varied from 2.7 mL in the OA group to 5.1 mL in the OAT group; concentration from 16.6 × 106/mL in the OT group to 17.1 × 106/mL in the oligozoospermic group; motility from 37.5% in the OAT group to 45.5% in the oligozoospermic and OT groups. The percent normal morphology varied from 2.5% in the OAT, to 8.5% in the oligozoospermic group.

Table 2. Receiver operator characteristic curves for semen parameters for oligozoospermic groups compared with normal donors.

When proven donors <2 years were compared, the cutoff ejaculate volume ranged from 3.5 mL in the oligozoospermic group to 5.1 mL in the OAT group; concentration from 21.3 × 106/mL in the OT group to 21.5 × 106/mL in the OA group; motility from 37.5% to 46% in the oligozoospermic and the OT groups. The cutoff for morphology ranged from 2.7% in the OAT group to 10% in the oligozoospermic group. The sensitivities, specificity, and the AUC are shown in the .

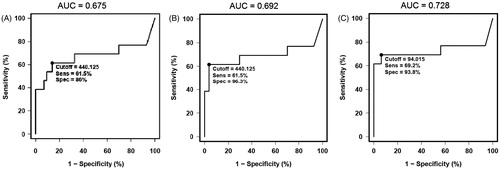

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for ROS

The lowest cutoff value for ROS with highest sensitivity, specificity, and the AUC was seen for all patients in the proven donors <2 year group. Reactive oxygen species cutoff of 94 relative light units/sec (RLU/s)× 106 sperm was seen in the oligozoospermic group. This group also demonstrated the highest sensitivity, specificity, and AUC compared with the proven donors and all donors. These cutoff values were higher for all patient groups in all donors as well as proven donors (; ).

Figure 2. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for reactive oxygen species (ROS) in (a): all donors vs. oligozoospermic patient group (b): proven donors vs. oligozoospermic patient group, and (c): proven donors <2 years of fertility vs. oligozoospermic patient group. Each ROC curve demonstrates the area under curve (AUC), cutoff, specificity, and sensitivity for each group. The cutoff for proven donors <2 years is significantly lower compared to all donors and proven donors >2 years of fertility.

Table 3. Receiver operator characteristic curves for ROS when oligozoospermic patients are compared with donor groups.

Correlations among semen parameters among the donors and patients

All correlations between concentration, motility, morphology, and levels of ROS in the three donor groups are shown in . Among the all donors group, percent normal morphology was related with concentration (r2 = 0.407; p = 0.009) and motility (r2 = 0.508; p = 0.001). A negative correlation was seen between levels of ROS and sperm concentration (r2 = −0.354; p = 0.021).

Among the proven donors, morphology was related with concentration (r2 = 0.481; p = 0.037) and motility (r2 = 0.494; p = 0.032); ROS showed a negative trend close to significance and was negatively related with sperm concentration (r2 = −0.377; p = 0.052). In the proven donor <2 years, concentration was associated with morphology (r2 = 0.733; p = 0.004). All other correlations for the three donor groups were not significant ().

Table 4. Correlation between various semen parameters in the three donor groups.

When patients were examined for an association between various semen parameters and ROS, in the oligoteratozoospermia (OT) group, percentage normal morphology was related with levels of ROS (r2 = 0.81; p = 0.001). In the OAT group, ejaculate volume was negatively correlated with morphology (r2 = −0.27; p = 0.05); sperm concentration was positively correlated with normal morphology (r2 = 0.27; p = 0.04). Sperm concentration showed a negative association with levels of ROS (r2 = −0.44; p = 0.001) (). All other correlations did not show significant differences.

Table 5. Correlation between semen parameters and ROS in the four study groups.

Discussion

Oligozoospermia is a common presentation in male infertility. Causes of oligozoospermia can be numerous, including high fever, smoking, alcohol and/or use of recreational drugs. Other causes could be obstruction, testicular trauma, chromosomal disorders, secondary testicular failure, varicocele, and sexually transmitted diseases. Hormonal disorders varicocele, obesity, and malnutrition can all result in oligozoospermia [McLachlan Citation2013]. Both poor motility and morphology are surrogate markers of poor sperm function.

The primary goal of this study was to examine how oligozoospermia compares with three control groups, i.e., men who are normal based only on their semen characteristics and not evaluated for infertility as well as those who are of proven fertility as established by a recent past pregnancy of a partner. Furthermore, we also examined how these parameters compare to the control group of men who had established a recent pregnancy (<2 years). The secondary goal of this study was to examine the ROS generated in the infertile men who were oligozoospermic as well as patients in the OA, OT, and OAT groups and establish the sensitivity, specificity, and the cut-off value of these characteristics using the ROC curves. Finally our last goal was to establish the reference range for the various semen parameters in the three donor and four patient groups by generating ROC curves for each parameter. This is important to see if these values are different than those established by the WHO [Citation2010] guidelines.

All donors (both proven and unproven) (group 1) as well as those men who had initiated a successful pregnancy at some point in the past (group 2), along with those with a pregnancy within the last 2 years (group 3), were compared with infertile patients. Among the donors, our results indicate that improvement in sperm concentration also results in improved motility or morphology. Many of the patients had some abnormality in their semen characteristics.

Reduced sperm concentration is a characteristic feature of oligozoospermic men, this was evident not only in the oligozoospermic group but in all groups examined, i.e., OAT, OA, and OT groups. This was seen all across the three donor groups. A significant decline in motility was seen in OAT and OA patients. These differences were comparable in all the three donor groups. Similarly a significant decline in normal sperm morphology was seen in the OAT and OT groups. Again this decline was comparable among the three donor groups. However, when comparing sperm concentration with ROS in OAT patients, a negative correlation was seen (r2 = −0.44; p < 0.001), indicating that a lower semen concentration correlates with a high amount of ROS and vice versa. Additional comparisons between donor groups and oligozoospermia, OAT, and the OA patients showed significantly higher levels of ROS, further indicating that ROS are implicated in the underlying mechanism of oligozoospermia. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis shows the diagnostic capabilities of these tests. The cutoff value in the oligozoospermic group was lowest in the proven donor <2 year group. Both the sensitivity and the specificity are high. Together with the high AUC consistently >0.72 suggests that ROS levels have a relatively good diagnostic capability.

Reactive oxygen species have been linked to the development of male infertility. They are hypothesized to originate from male accessory glands, by both abnormal spermatozoa and leukocytes. They are hypothesized to induce oxidative stress in spermatozoa and damage DNA [Villegas et al. Citation2005] as well as ATP production [De Lamirande and Gagnon Citation1992], leading to impairment of sperm functionality. When sperm DNA is damaged by oxidative stress, oocyte fertilization and pregnancy can be affected [Aitken and Koppers Citation2011]. Further studies by Henkel and colleagues looked at in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) outcomes in patients with sperm DNA damage [Henkel et al. Citation2003]. These outcomes were poor, with a lower pregnancy rate in women fertilized by DNA damaged sperm [Henkel et al. Citation2003]. A subsequent study examined the effects of severe oligozoospermia on ICSI cycle outcomes. Severely oligozoospermic patients had a significantly lower percentage of two pronuclei oocytes, indicating that good quality sperm is important for oocyte injection [Hashimoto et al. Citation2010]. A retrospective study examined patients with oligozoospermia undergoing ICSI and concluded that the fertilization rate was significantly lower in groups with semen concentration less than 107 sperm/mL [Arikan et al. Citation2011]. These studies demonstrate poor outcomes in the realm of ICSI when male patients with either oxidative stress or oligozoospermia were involved. This should be of particular interest to physicians treating patients with either of these qualities when considering assisted reproductive technologies (ART). In addition it points to the need to delve further for a treatment angle to prevent poor outcomes for these patients.

A previous study from our group has shown that semen samples with high levels of ROS also had significantly higher amounts of DNA damage and significantly poorer motility than those with lower levels of ROS [Mahfouz et al. Citation2010]. As previously mentioned, the chain of oxidative stress leading to DNA damage can affect oocyte fertilization and pregnancy outcomes, a primary goal for infertile patients. This indicates a relationship between infertility, ROS, and DNA damage, and poor semen quality.

Currently, WHO guidelines state that less than 15 × 106 sperm/mL constitutes a man as oligozoospermic [Cooper et al. Citation2010; WHO Citation2010]. These patients are commonly infertile, with the most common cause of infertility deemed as idiopathic failure of spermatogenesis [Dohle et al., Citation2005]. Mechanisms of oligozoospermia have been reported to lie within chromosomal abnormalities [Montjean et al. Citation2012; Pylyp et al. Citation2013; Zhang et al. Citation2012]. Sperm characteristics compared between fertile and infertile men are significantly higher in men with proven fertility [Nallella et al. Citation2006]. This indicates a relationship between fertility and normal semen characteristics. It follows then, that there is also a relationship between infertility and abnormal semen characteristics.

Lipid peroxidation is an end product of ROS induced sperm damage. It can be measured as a function of the concentration of malondialdehyde (MDA), a byproduct of oxidative stress, forming after polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) undergo auto−oxidation [Pryor and Stanley Citation1975]. Significantly higher spermatozoa concentration of MDA was reported in men with asthenozoospermia and oligoasthenozoospermia [Suleiman et al. Citation1996]. A recent study has confirmed that the levels of MDA are significantly higher (p < 0.0001) in infertile patients as compared to fertile donors [Kumar et al. Citation2009]. These investigators also found that OA patients had structural abnormalities of microtubular arrangement, with microtubules being either disorganized or absent in 43% of the cases [Kumar et al. Citation2009]. Additionally, positive correlations have been determined between MDA, DNA fragmentation, and sperm ROS content [Aktan et al. Citation2013]. With this negative association between MDA and sperm motility and morphology, we can assume that MDA, or oxidative damage, negatively affects sperm quality. This is a key indication as to why our study showed a relationship between ROS and poor semen concentration. However, we did not examine DNA damage, typcially by comparing the amount of DNA fragmentation for donors vs. infertile men as that relates to ROS. This may have an impact on overall sperm count. We additionally were unable to examine follow up in terms of pregnancy and the use of ART.

In conclusion, our study is unique in that we examined two proven donor groups to include men who have established a pregnancy in the past to those who have recently initiated a pregnancy to show that semen parameters change over a period of time and proper controls are critical for accurate establishment of reference values for various semen parameters. Measuring ROS levels is an important indicator of sperm quality. Establishing the reference values for these parameters in men with different combinations of oligozoospermia may help in the management of this group of patients.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by our institutional review board, and written consent was obtained from all patients involved. In this cross-sectional study, 374 subjects were examined and divided into healthy donors (n = 56) and infertile patients (n = 318). The inclusion criteria for infertile men were: (1) all subjects attended the male infertility clinic for fertility issues; (2) all were evaluated for proven male-factor infertility as assessed by the male infertility specialist; (3) all underwent a history, physical, and laboratory evaluation; and (4) none had female factor infertility in their partners. The exclusion criteria were azoospermia, or incomplete semen analysis results, or inadequate semen sample for measurement of ROS.

Our interest was patients with oligozoospermia and a combination of poor motility and morphology or both. A total of 139 patients were selected and examined for infertility status (primary vs. secondary). Thirty-eight patients were excluded due to incomplete semen analysis results or inadequate semen sample for measurement of ROS. Finally, 101 patients were selected and divided into: oligozoospermia (<15 × 106 sperm/mL): n = 16 (5%); oligoasthenozoospermia (<15 × 106 sperm/mL and poor motility <40%): n = 12 (3.8%); oligoteratozoospermia (<15 × 106 sperm/mL and poor morphology <4% normal forms): n = 19 (6%); oligoasthenoteratozoospermia (<15 × 106 sperm/mL and poor motility and morphology): n = 54 (17%).

Controls consisted of three groups: group 1 (n = 56): healthy men of proven and unproven fertility. Inclusion criteria for this group were: (a) normal semen parameters; (b) no sexually infected disease; (c) no use of recreational drugs, and (d) may or may not have initiated a pregnancy in the past. Group 2 (n = 28): men who had initiated a pregnancy at some point. The Inclusion criteria were: (a) normal semen parameters; (b) no sexually infected disease; (c) no use of recreational drugs, and (d) initiated a pregnancy in the past. Group 3 (n = 12): men had initiated a pregnancy in the past two years. The Inclusion criteria were: (a) normal semen parameters; (b) no sexually infected disease; (c) no use of recreational drugs, and (d) initiated a recent pregnancy in the past 2 years.

Semen analysis

Semen samples were collected by masturbation after 2–3 d of sexual abstinence. Following complete liquefaction, manual semen analysis was performed using a MicroCell counting chamber (Vitrolife, San Diego, CA, USA) to determine sperm concentration and percentage motility according to WHO [Citation2010] guidelines [Cooper et al. Citation2010]. Viability was determined with Eosin-Nigrosin stain. Smears were stained with a Diff-Quik kit (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Inc., McGaw Park, IL, USA) for assessment of sperm morphology according to WHO [Citation2010] criteria [Cooper et al. Citation2010].

White blood cell measurement

When the round cell concentration in the ejaculate was >1 × 106/mL or >5 round cells per high power field, sample was tested for Leukoctyospermia. i.e., >1 × 106 WBC/mL. This was confirmed by the peroxidase or the Endtz test. A 20 µL well mixed aliquot of the semen sample was mixed with one volume of PBS and 2 volumes of working Endtz solution in an amber colored eppendorf tube [Sharma et al. Citation2013]. After 5 min, a drop of the aliquot was placed on a Makler chamber and examined for the presence of dark brown cells under a ×10 bright field objective.

ROS measurement

Reactive oxygen species was measured by the chemiluminescence assay method using luminol (5-amino-2,3-dihydro- 1,4-phthalazinedione; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA) as the probe. Ten microliters of 5 mmol/L luminol prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma Chemical Co, MO, USA) were added to 400 mL of the washed sperm suspension. Levels of ROS were determined by measuring chemiluminescence with an Autolumat LB 953 luminometer (AutoLumat Plus LB 953, Oakridge, TN, USA) in the integrated mode for 15 min. The results were expressed as relative light units (RLU/sec) [Kashou et al. Citation2013].

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were summarized as Mean ± SD, except for ROS where median and 25th, 75th percentiles were used. Box plots were used to display the distributions of quantitative variables with respect to their quartiles, and the 5th and 95th percentiles. Group comparisons with respect to categorical variables were performed with Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test. Group comparisons with respect to the quantitative variables were performed with the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. Receiver operating characteristic curve analyses were performed to assess the ability to classify subjects into donor or patient groups based on the individual quantitative parameters. Correlations were assessed by Spearman correlation; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Declaration of interest

This study received financial support from the Center for Reproductive Medicine, Cleveland Clinic. The authors report no declaration of interest.

Author contributions

Conceived the idea, supervised the study, and edited the article for submission: AA; Assisted with data analysis, literature review, writing of manuscript, and preparation for submission: AM; Helped with the reviewing and editing of the manuscript: RS, ES.

| Abbreviations | ||

| ROS | = | reactive oxygen species |

| ROC | = | receiver operating characteristic |

| OA | = | oligoasthenozoospermia |

| OT | = | oligoteratozoospermia |

| OAT | = | oligoasthenoteratozoospermia |

| AUC | = | area under curve |

| ICSI | = | intracytoplasmic sperm injection |

| ART | = | assisted reproductive technologies |

| MDA | = | malondialdehyde |

Acknowledgments

Amy Moore helped with medical editing of the manuscript and Jeff Hammel performed statistics for this experiment. Authors wish to thank the members of the Andrology Center for their help in scheduling the study subjects.

References

- Agarwal, A., Makker, K. and Sharma, R. (2008) Clinical relevance of oxidative stress in male factor infertility: an update. Am J Reprod Immunol 59:2–11

- Aitken, R.J. and Koppers, A.J. (2011) Apoptosis and DNA damage in human spermatozoa. Asian J Androl 13:36–42

- Aktan, G., Dogru-Abbasoglu, S., Kucukgergin, C., Kadioglu, A., Ozdemirler-Erata, G. and Kocak-Toker, N. (2013) Mystery of idiopathic male infertility: is oxidative stress an actual risk? Fertil Steril 99:1211–5

- Arikan, I., Demir, B., Bozdag, G., Esinler, I., Sokmensuer, L. and Gunalp, S. (2011) ICSI cycle outcomes in oligozoospermia. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 39:280–2

- Cavallini, G. (2006) Male idiopathic oligoasthenoteratozoospermia. Asian J Androl 8:143–57

- Cooper, T.G., Noonan, E., Eckardstein, S.V., Auger, J., Baker, H.W.G., Behre, H.M., et al. (2010) World Health Organization reference values for human semen characteristics. Hum Reprod Update 16:231–45

- De Lamirande, E. and Gagnon, C. (1992) Reactive oxygen species and human spermatozoa. J Androl 13:379–86

- De Palma, A., Burrello, N., Barone, N., D'Agata, R., Vicari, E. and Calogero, A.E. (2005) Patients with abnormal sperm parameters have an increased sex chromosome aneuploidy rate in peripheral leukocytes. Hum Reprod 20:2153–6

- Desai, N., Sharma, R., Makker, K., Sabanegh, E. and Agarwal, A. (2009) Physiologic and pathologic levels of reactive oxygen species in neat semen of infertile men. Fertil Steril 92:1626–31

- Dohle, G.R., Colpi, G.M., Hargreave, T.B., Papp, G.K., Jungwirth, A., Weidner, W., et al. (2005) EAU guidelines on male infertility. Eur Urol 48:703–11

- Guz, J., Gackowski, D., Foksinski, M., Rozalski, R., Zarakowska, E., Siomek, A., et al. (2013) Comparison of oxidative stress/DNA damage in semen and blood of fertile and infertile men. PLoS One 8:e68490

- Hashimoto, H., Ishikawa, T., Goto, S., Kokeguchi, S., Fujisawa, M. and Shiotani, M. (2010) The effects of severity of oligozoospermia on intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycle outcome. Syst Biol Reprod Med 56:91–5

- Henkel, R., Kierspel, E., Hajimohammad, M., Stalf, T., Hoogendijk, C., Mehnert, C., et al. (2003) DNA fragmentation of spermatozoa and assisted reproduction technology. Reprod Biomed Online 7:477–84

- Kashou, A.H., Sharma, R. and Agarwal, A. (2013) Assessment of oxidative stress in sperm and semen. Methods Mol Biol 927:351–61

- Kullisaar, T., Türk, S., Kilk, K., Ausmees, K., Punab, M. and Mändar, R. (2013) Increased levels of hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide in male partners of infertile couples. Andrology 1:850–8

- Kumar, R., Venkatesh, S., Kumar, M., Tanwar, M., Shasmsi, M.B., Kumar, R., et al. (2009) Oxidative stress and sperm mitochondrial DNA mutation in idiopathic oligoasthenozoospermic men. Indian J Biochem Biophys 46:172–7

- Mahanta, R., Gogoi, A., Chaudhury, P.N., Roy, S., Bhattacharyya, I.K. and Sharma, P. (2012) Association of oxidative stress biomarkers and antioxidant enzymatic activity in male infertility of north–East India. J Obstet Gynaecol India 62:546–50

- Mahfouz, R., Sharma, R., Thiyagarajan, A., Kale, V., Gupta, S., Sabanegh, E., et al. (2010) Semen characteristics and sperm DNA fragmentation in infertile men with low and high levels of seminal reactive oxygen species. Fertil Steril 94:2141–6

- McLachlan, R.I. (2013) Approach to the patient with oligozoospermia. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 98:873–80

- Milardi, D., Grande, G., Sacchini, D., Astorri, A.L., Pompa, G., Giampietro, A., et al. (2012) Male fertility and reduction in semen parameters: a single tertiary–care center experience. Int J Endocrinol 2012:649149 . doi: 10.1155/2012/649149

- Montjean, D., De La Grange, P., Gentien, D., Rapinat, A., Belloc, S., Cohen–Bacrie, P., et al. (2012) Sperm transcriptome profiling in oligozoospermia. J Assist Reprod Genet 29:3–10

- Nallella, K.P., Sharma, R.K., Aziz, N. and Agarwal, A. (2006) Significance of sperm characteristics in the evaluation of male infertility. Fertil Steril 85:629–34

- Pant, P. (2013) Abnormal Semen Parameters among Men in Infertile Couples. Nepal Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 8:53--5

- Pryor, W.A. and Stanley, J.P. (1975) Suggested mechanism for the production of malonaldehyde during the autoxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Nonenzymic production of prostaglandin endoperoxides during autoxidation. J Org Chem 40:3615–7

- Pylyp, L.Y., Spinenko, L.O., Verhoglyad, N.V. and Zukin, V.D. (2013) Chromosomal abnormalities in patients with oligozoospermia and non-obstructive azoospermia. J Assist Reprod Genet 30:729–32

- Rowe, P., Comhaire, F., Hargreave, T. and Mahmoud, A. (2000) WHO Manual for the Standardized Investigation, Diagnosis, and Management of the Infertile Male, Cambridge Geneva, Switzerland: University Press

- Sharma, R., Agarwal, A., Mohanty, G., Jesudasan, R., Gopalan, B., Willard, B., et al. (2013) Functional proteomic analysis of seminal plasma proteins in men with various semen parameters. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 11:38–7827-11-38 . doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-11-38

- Suleiman, S.A., Ali, M.E., Zaki, Z.M., el-Malik, E.M. and Nasr, M.A. (1996) Lipid peroxidation and human sperm motility: protective role of vitamin E. J Androl 17:530–7

- The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (2012) Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile male: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 98:294--301

- Villegas, J., Schulz, M., Soto, L., Iglesias, T., Miska, W. and Sánchez, R. (2005) Influence of reactive oxygen species produced by activated leukocytes at the level of apoptosis in mature human spermatozoa. Fertil Steril 83:808–10

- WHO (2010) World Health Organization laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen. 5th edition. Geneva, Switzerland

- Zhang, Z.B., Jiang, Y.T., Yun, X., Yang, X., Wang, R.X., Dai, R.L., et al. (2012) Male infertility in Northeast China: a cytogenetic study of 135 patients with non-obstructive azoospermia and severe oligozoospermia. J Assist Reprod Genet 29:83–7