Abstract

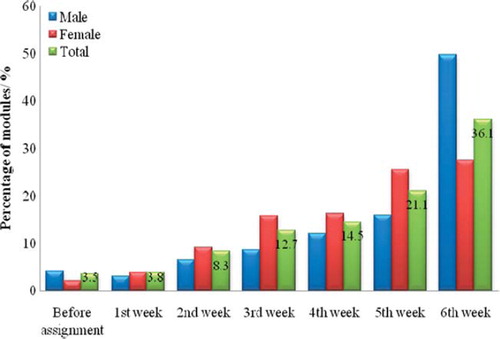

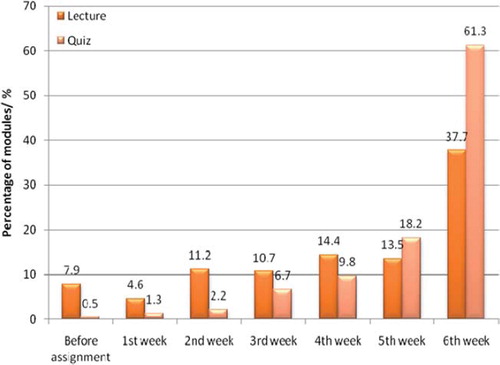

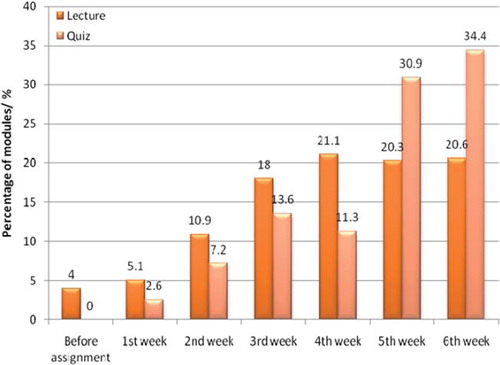

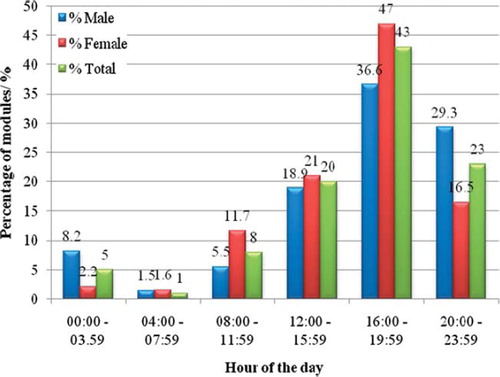

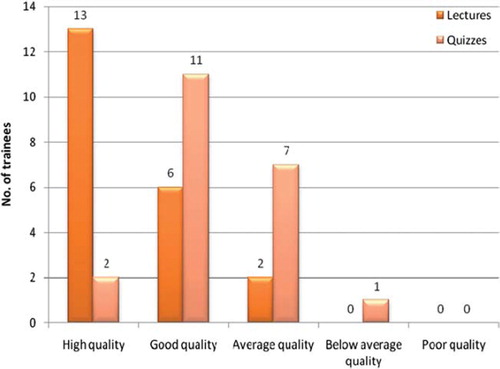

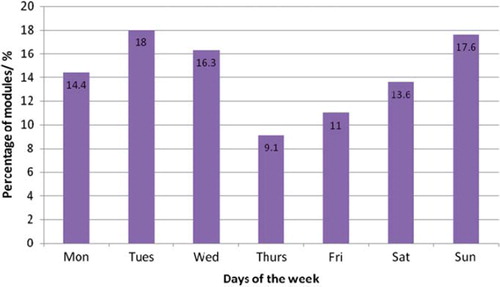

Introduction. E-learning is a useful tool providing after-hours access to continuous Medical Education and the theoretical component of postgraduate medical trainings. Furthermore, it allows accurate recording of trainee activity. Objective. To observe the pattern of usage by trainees and to assess feedback on e-learning use. Method. A modular object-oriented dynamic learning environment (Moodle) online e-learning management system – including 24 online modules relevant to different medical specialities and 24 quizzes. All 23 (14 Female) medical ‘Common-trunk’ trainees at Mater Dei Hospital, Malta were asked to complete these modules as part of their compulsory academic activities within a 6-week deadline. Data on usage was collected by the learning management system and trainees were asked to fill in an online feedback form. Results. All trainees (n = 23) completed all modules; however, 36.1% of modules (M = 49.8%, F = 27.4%) were completed in the last week. Nineteen (n = 21) trainees found the e-learning as a useful or very useful tool. 19/21 Students reported presentations as being of good/high quality and 13/21 reported quizzes to be of a good/high quality standard. Self-rating of acquisition of new knowledge was 7.95 (SD 1.75) on a scale of 0–10. The quality of IT work was rated 7.81 (SD 1.86). Forty-three percent (M 36.6%, F 47.0%) of modules were completed from 16:00 hours to 19:59 hours; 16.5% (M = 29.3%, F = 16.5%); from 20:00 hours to 23:59 hours and 4.5% (M = 8.2%, F = 2.2%) from 00:00 hours to 03:59 hours. A total of 31.2% of modules were performed during weekends (Sat = 13.6%, Sun = 17.6%, Average Mon–Fri = 13.8%). Average time to complete learning module: F = 49.7 minutes, M = 76.4 minutes. Conclusion. Overall feedback on e-learning was positive. There was significant after hour and weekend use. Gender differences in time of access and total time needed to complete modules were noted.

Introduction

E-learning refers to the use of internet technologies to deliver knowledge. Given the fast pace of advances in medicine, the educator has to consume much more time in continuous professional development than ever before. Furthermore, trainees with busy clinical schedules have limited time for formal academic activities during working hours. E-learning provides a solution by providing an efficient way of distributing to many users, even if they are geographically dispersed, the delivery of both continuing medical education and postgraduate training. It is also easy to update and standardise content.Citation1 By making use of password protection, educators can protect intellectual property rights online and give access only to registered users.Citation2 Learning management systems also allow accurate recording of trainee activity.

Another advantage is that users are able to use the system at their chosen convenience, both in time and place. This flexibility gives the opportunity to doctors with busy clinical schedules to view the lecture or conference which they would have otherwise missed.Citation1 A literature review by Lau et al. on e-learning usage during the preclinical years showed that most of the teaching is done to enhance individualised learning and only few report synchronised real-time delivery of lectures and tutorials.Citation3

At postgraduate level, motivation to educate oneself is driven by relevance to clinical practice whereas at undergraduate level, curriculum and examinations usually motivate students.Citation4 With web-based learning, physicians can access the appropriate material easily and retention of information is more likely to be fruitful.Citation5 Integrating e-learning as part of the curriculum and having dedicated time at work to make use of e-learning would also help. Being able to blend teaching, that is, making use of e-learning and at the same time having face-to-face teaching would also reinforce learning.Citation6 By making use of e-learning systems one would also reduce or even eliminate costs associated with travelling.Citation5

After graduating from medical school, it takes 8 years to become a medical specialist in Malta. Two years as a foundation doctor, 2 years as common-trunk trainee and 4 years as a higher specialist trainee in the particular field. Since 2007, doctors training in Malta could make use of an e-learning management system to supplement their training.

The aim of our study was to observe the usage pattern by common-trunk trainees while using the e-learning system. Feedback from trainees with regards to the use of e-learning systems as an educational tool was also collected. The information collected would help determine whether the introduction of such a system which involved considerable financial investment, time and effort, was a useful add-on to postgraduate training. To our knowledge, there have been no studies on e-learning and Maltese medical trainees to date.

Methods

The setting up of an e-learning management system was part of an EU-funded project ESF 1.19 Malta. The modular object-oriented dynamic learning environment (moodle) version 1.9.2 online e-learning management system was used (http//www.esf-mam.net/moodle2). Departmental lectures in Medicine were recorded and streamed using Articulate Presenter® version 05 and later 2009 software, while quizzes on the relevant lecture were prepared using Articulate Quizmaker® version 05 and later 2009. PowerPoint® presentations were integrated with recorded sound, and lectures could be streamed. All software was sharable content object reference model (SCORM) compliant so that the learning management system could keep accurate track of participants. SCORM is a set of technical standards for e-learning software products, which is the de facto industry standard for e-learning software interoperability.

Lecture topics included cardiology, respiratory, gastroenterology, haematology, geriatric medicine, infectious disease, neurology, rheumatology and nephrology. Lectures streamed were part of the live lectures delivered by consultant trainers for core medical training programme. Quizzes were then formulated on the basis of material covered in these lectures. Questions were prepared by senior medical students, under the supervision of at least one consultant. The e-learning management system was accredited by the Specialist Accreditation Committee of Malta.

All 23 (14 female) common-trunk trainees in the Department of Medicine at Mater Dei Hospital were required to complete 24 online lectures and 24 quizzes as part of their compulsory academic activities within a 6-week deadline. Failure to complete the lectures would lead to negative comments on a 4 monthly appraisal form which was used to assess trainee performance. Trainees were aware that the learning management system accurately recorded their online activity.

At the end of the assignment the trainees were asked to fill in an online feedback form (vide Appendix 1) which was completely anonymous.

Statistics

Chi squared test was used to compare distribution of access of modules, by week, time of day or Gender with Predicted Distribution. Regression analysis was also used to analyse variation by week. Minitab 16 software was used.

Results

All 23 trainees completed the training. As there was no limit to the number of attempts on the quizzes, trainees tended to repeat the quiz till they had full marks. shows the percentage of modules completed by all trainees till the deadline set for the assignment, with a progressive rise as the deadline approached. (Males Chi p = 0.03, R>2 = 0.63, Females Chi p < 0.001, R2 = 0.95). and compare the percentage distribution of lectures and quizzes completed by trainees (males and females, respectively) every week till the end of the assignment. Regression lines were different for quizzes and lectures, (Females p = 0.03, Males p = 0.01 using lecture modules as reference trend) showing that quizzes tended to follow the lecture at a later date. shows the percentage of the modules and the time of the day used by trainees. Totals show significant after-hours use (chi p = 0.001). Males have a different distribution than females with significantly higher late night use (p < 0.01).

Twenty-one trainees filled in feedback forms. shows that 19/21 and 13/21 trainees rated the educational content (Question 1, 2) as being of high/good quality for lectures and quizzes, respectively (p = 0.02). There was no significant difference, however, as to the rating of the IT quality of lectures 7.61(SD 1.6) and quizzes 7.81 (SD 1.86) out of a score of 0–10 (Question 5, 6). Acquisition of new knowledge from the e-learning system (Question 3) was rated at 7.95(SD 1.75) out of 10. Nineteen out of 21 trainees rated the e-learning system as a useful or very useful tool (Question 4).

shows the distribution of access to modules by the day of a week, showing significant week-end use (p < 0.01). The actual average duration of an online lecture module was 35 minutes. Female trainees took an average of 49.7 minutes per lecture module while male trainees took 76.4 minutes per module.

Discussion

This was a descriptive study, trying to assess the utility and the feedback on the introduction of a new e-learning tool, in a traditional curriculum which is mostly hands-on clinical experience with planned and structured rotations. Two traditional (1 hour each) live lectures per week mainly relating to theoretical knowledge are part of the programme, while one or two tutorials per week prepare trainees for their membership examination, mainly membership of the royal colleges of physicians (MRCP (UK)) parts one to three.

As e-learning was incorporated as part of an official programme, compliance was high. However, a tendency for last minute panic in our study was evident as 36.1% of the modules and quizzes were completed during the last week. This tendency was more pronounced in males than in females. There was a peak in lectures done during the last week by males which was not present in the case of females, who showed a steady regression line to the deadline.

When one analyses time of access of modules by both genders, quizzes were not accessed immediately after lecture modules but usually at a later date. This might indicate that trainees wanted first to reflect on the content of the lecture module.

Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Sundays were the most popular days of the week. A heavy use of the e-learning system during weekends was noticed confirming the benefits of flexibility this system offers. Unless a trainee is on call, usual working hours in Malta would be from 7:45 hours till 14:30 hours. An insignificant amount of online modules were accessed during this time. One might also argue that e-learning may impinge on trainee's free time; however, the questionnaire to trainees did not collect information on this issue.

Most of the modules completed by females were between 16:00 hours and 20:00 hours. Only a minimal number of the modules were done during the night. On the other hand in male trainees, usage after 20:00 hours was more prominent. This could be due to the fact that males finished around 50% of the modules in the last week and the only way to do that was by working at night.

The e-learning management system allowed the user to pause any particular presentation. However, it still recorded the total time required to complete the module. Most trainees, particularly males, took longer to complete a lecture, possibly due to the fact that they took frequent breaks while viewing one. Yet the possibility that some trainees were manipulating the system with regard to periods when the user was not in front of the computer cannot be excluded.

Trainees rated the e-learning tool to be of high quality and educational benefit. Similarly, several studies show that user satisfaction with e-learning is high and that students felt it complements traditional instructor-led training.Citation1,Citation7 Recent randomised controlled studies done by Davis et al. and other studies carried out by Kulier et al. on postgraduate doctors showed that e-learning is at least equivalent to traditional teaching methods in contributing to learning.Citation4,Citation8 Some non-medical literature has shown that when comparing e-learning to the traditional methods, there is significant cost-saving, as much as 50%.Citation1,Citation5

One of the main obstacles of web-based learning is technology rather than the design of learning material. Examples of poor technology would be poor access, slow downloading and software errors which could frustrate learners and may militate against further use of the e-learning.Citation2 In our study, when trainees were asked to rate the quality of IT work on streamed lectures and quizzes, from a scale of one to ten the means were 7.76 (SD 1.67) and 7.81 (SD 1.86), respectively. This may have encouraged learning by this method and also made it pleasurable to use. While all trainees had access to broadband, help was needed by a tutor initially to access the system; however, trainees picked it up very quickly after the first modules.

While the main advantage of streamed lectures is the ability of users to access modules at their own convenience, the insertion of online quizzes in the form of multiple-choice questions did present the users with an opportunity for interactivity.

In this study, 19/22 of trainees rated the modules as a useful or very useful educational tool. Most trainees stated that they had acquired new knowledge through the e-learning system. Furthermore, trainees consistently completed quizzes until full marks were obtained. Trainees rated the educational content of the streamed lectures, higher than that of the quizzes. This may have been because streamed lectures were delivered by senior consultants, whereas questions were prepared by medical students.

We did not assess the long-term retention of knowledge, and perhaps this is an area which would need further research. Furthermore, in view of the compulsory nature of the exercise, it is possible that trainees were reluctant to criticise it openly.

Although this study focused on the theoretical element of postgraduate medical training, it is reasonable to presume that many of the findings may be applicable to the delivery of continuing medical education.

Conclusion

This study shows that the flexibility of an e-learning system allows the trainees to access lectures at times they find convenient. However, there were gender differences in the pattern of usage. The e-learning system used was rated as being of good IT quality, and, probably, as a result, high levels of satisfaction were expressed with regard to the educational value of the system, with most trainees finding the system a useful tool in acquiring new knowledge even though it was part of a compulsory curriculum.

This study suggests that incorporation of e-learning into postgraduate common trunk training in Internal Medicine represents a useful investment for busy postgraduate trainees.

Declaration of interest

Funding

Part of European Social Fund (Malta) ESF 1.19 (Online E-Learning Management System for Post-graduate Medical Training)

Author(s) Financial Disclosure

J.B. has disclosed that she has no relevant financial relationships.

D.B. has disclosed that he has no relevant financial relationships.

M.B. has disclosed that he has no relevant financial relationships.

Peer Reviewers Financial Disclosure

Peer Reviewer 1 has disclosed that he has no relevant financial relationships.

Peer Reviewer 2 has disclosed that he has no relevant financial relationships.

Appendix 1: Online feedback form

1. How do you rate the educational content of the lectures? high quality, good quality, average quality, below average quality, poor quality.

2. How do you rate the educational content of the quizzes? high quality, good quality, average quality, below average quality, poor quality.

3. From a scale of one to ten do you feel that you have learnt new knowledge from these modules?

4. As regards to E-learning - what is your preferred answer? very useful tool, useful tool, no option, limited use, useless.

5. From a scale of one to ten how do you rate the quality of the IT work on the streamed lectures?

6. From a scale of one to ten how do you rate the quality of the IT work on the streamed quizzes?

References

- Ruiz JG, Mintzer MJ, Leipzig RM. The impact of E-learning in medical education. Acad Med 2006;81:207–212.

- McKimm J, Jollie C, Cantillon P. Web based learning. BMJ 2003;326:870–873.

- Lau F, Bates J. A review of e-Learning practices for undergraduate medical education. J Med Syst 2004;28:71–87.

- Davis J, Chryssafidou E, Zamora J, . Computer-based teaching is as good as face to face lecture-based teaching of evidence based medicine: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Educ 2007;7:23.

- Hishamuddin Harun M. Integrating e-learning into the workplace. Internet High Educ 2002;4:301–310.

- Childs S, Blenkinsopp E, Hall A, . Effective e-learning for health professionals and students – barriers and their solutions. A systematic review of the literature – finding from the HeXL project. Health Inform Libr J 2005;22:20–32.

- Link TM, Marz R. Computer literacy and attitudes towards e-learning among first year medical students. BMC Med Educ 2006;6:34.

- Kulier R, Coppus SFPJ, Zamora J, . The effectiveness of a clinically integrated e-learning course in evidence-based medicine: A cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Educ 2009;9:21.