Summary

This observational database study estimates the comparative cost effectiveness of salbutamol when delivered via a pressurised metered-dose inhaler (pMDI) or breath-actuated metered-dose inhaler (BAI) in patients with mild intermittent asthma who have changed from a pMDI to either a different pMDI or a BAI.

Salbutamol use in the BAI cohort in the 12 months following the index event was 42% (p<0.001) of that in the pMDI cohort. Patients in the BAI cohort were more likely to require steroids (20 versus 16%, not significant) and had 10% fewer asthma consultations (1.01 vs. 1.11, p<0.001) in the 12-month period following the index event.

To control for potentially confounding differences in the patient cohorts, a regression analysis was undertaken to identify the impact of individual elements in the analysis. The results of this controlled analysis identified that despite controlling for such factors, significantly less (p<0.001) salbutamol was still consumed in the BAI cohort. This result would seem to emphasise the enhanced efficiency and reduced wastage associated with BAI in real-world clinical practice. However, the cost analysis found that BAI would require a 27.5% reduction in unit price (i.e. from the current weighted unit price of £6.25 to £4.23) in order to result in the same unit prescription costs as pMDI.

Key words::

Introduction

Inhaled medication for asthma is available via a variety of inhaler devices. Traditional pressurised metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs) have been available for over half a century, but more recently breath-actuated metered-dose inhalers (BAIs) and dry powder inhalers (DPIs) have become available. BAIs are designed to actuate on inspiration and hence overcome the well-documented difficulties that some patients have in coordinating inspiration with actuation of the device in traditional pMDIs. Breath-actuated inhalers are generally accepted to be easier to use than traditional pMDIsCitation1,Citation2, and seem to be generally preferred by patients and by healthcare professionalsCitation3.

Up to three quarters of patients using pMDIs make at least one mistake in their techniqueCitation4–7 thus reducing the amount of drug received by the patientCitation5,Citation8,Citation9. Such mistakes have been shown to reduce the overall level of asthma control in direct proportion to the number of mistakes made for both inhaled corticosteroidsCitation10 and beta agonistsCitation11.

Previous studies have demonstrated a significant difference in the pattern and levels of resource utilisation in patients prescribed inhaled steroidsCitation12 and beta agonistsCitation13,Citation14 via BAI compared with a traditional pMDI. BAIs have been found to be more cost effective for such patientsCitation15 due to the more effective delivery of medicine to the site of action. It seems reasonable, therefore, to hypothesise that patients using BAIs for the delivery of inhaled short-acting beta agonists may also demonstrate clinical and economic benefits. Indeed, a previous study has demonstrated a 23% reduction in the use of inhaled beta agonists in patients using a breath-actuated device when compared with a pMDICitation13.

Database analyses effectively capture the real-world clinical decision making of GPs and its effect on the pattern of resource use in patients treated in mainstream clinical practice. Such databases, however, are limited by the information routinely recorded. In particular, objective measures of asthma symptoms such as lung function, symptoms and quality of life are not recorded in most databases. Guidelines recommend using the level of usage of salbutamol as an indicator of the severity of symptoms in patients with mild intermittent asthmaCitation16,Citation17. For patients at step 1 of the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN) asthma guidelines, salbutamol use may, therefore, be used as a surrogate marker for the prevalence and severity of symptoms and hence the level of asthma control.

Cegedim Strategic Data UK Patient Longitudinal Database

The Cegedim Strategic Data UK Patient Longitudinal Database (CSD PLD) covers 100 nationally distributed general practices in the UK, representing >400 GPs and 840,000 registered patients. A General Medical Council-approved system extracts and anonymises the coded data to a central database. The coding system used for both drugs and diagnoses is Read, the UK standard for clinical data coding. In addition, a Front Desk system records interventions by other practice staff. The socioeconomic profile of the standard panel closely matches that of the UKCitation18.

In comparison to disease registers and other surveillance databases, CSD PLD contains less detailed clinical data but accurately reflects the characteristics of UK patients, which enhances the representativeness of the results obtained. The database reflects treatment provided in a naturalistic environment in which patients are oblivious to treatment evaluationCitation19, thereby eliminating bias relating to patient selection or recallCitation20. The database also contains sufficient detail to allow the identification of potentially confounding differences between the patient groups being compared. Having identified such confounders, a range of modelling techniques can be employed to adjust the analysis to ensure that any bias resulting from systematic differences between the patient groups being compared can be adjusted for in relation to the size and importance of the variable in introducing potential bias into the analysis. The two most frequently used methods are propensity score analysis and Cox proportion hazard models. However, it is important to recognise that such adjustments can only encompass known confounders and residual confounding may result from unobserved variablesCitation21.

Study methods

Study hypothesis

The initial hypothesis was that patients with mild intermittent asthma using a BAI for relief of symptoms will be receiving their drug more efficiently than those using a pMDI, leading to clinical and resource benefits in the cohort of patients using the BAI. What was less certain was the extent to which such benefits would be sufficient to outweigh the additional acquisition costs associated with BAIs.

A retrospective observational database study was undertaken comparing the cost effectiveness of patterns of healthcare interventions for asthma in two groups of patients with mild intermittent asthma:

Patients inhaling salbutamol via a traditional pMDI

Patients inhaling salbutamol via a BAI

The pattern of healthcare usage was analysed for UK primary care patients using the CSD PLD database.

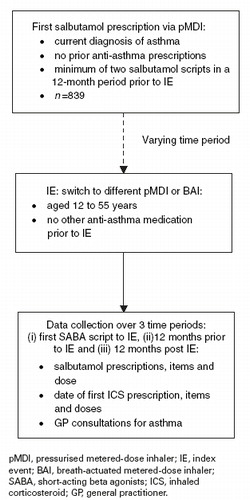

An index event (IE) was identified as being a change of prescription from a salbutamol pMDI to either a different salbutamol pMDI or to a salbutamol BAI.

A change of pMDI was used in order to identify a common event in both cohorts.

Patient cohorts

Salbutamol can be prescribed either on an ‘as-required’ basis for the relief of asthma symptoms, or on a ‘one-off’ basis for a range of other respiratory conditions such as allergy. In order to identify patients at step 1 of the BTS/SIGN asthma guidelines more closely (i.e. patients with mild intermittent asthma) a number of restrictions were applied to the data analysis. As such, in order to enter the study, patients had to have a current recorded diagnosis of asthma, as well as:

being aged between 12 and 55 years old on the date of the IE

having received at least two prescriptions for inhaled salbutamol during any 12-month period since the date of diagnosis

having received no other inhaled anti-asthma medication during the 12-month period of analysis prior to the IE

having at least 12 months continuous registration at the current practice in order to screen out patients moving between practices.

A study algorithm is shown in .

A total of 839 patients were included in the analysis of which 33% were in the cohort that was switched to a BAI and 67% were in the pMDI cohort. The baseline characteristics of both patient cohorts are provided in . No element of patient selection arose as the study analysed the total number of patients in the database that accorded with the patient criteria. The balance of patients (two-thirds pMDI, one-third BAI) again simply reflected the balance of treatment provided to eligible patients in the database. As such, no element of randomisation was employed as the allocation of patients to the two arms of the study reflected the real-world preferences and choices of patients and clinicians. While such a process coincides with the real-world focus of such analyses, it also introduces the possibility of systematic bias between patients in different arms of the study.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and prior resource consumption.

Analysis of emphasises that the patient cohorts were similar in terms of age, socioeconomic characteristics and gender. However, the patient cohorts differed significantly in terms of their prior use of salbutamol, both in total and over the 12-month period prior to the IE. Patients who subsequently remained on pMDI following the IE had, on average, received 28% more prescriptions for salbutamol and consumed 50% more salbutamol than patients subsequently transferring onto BAI. Such a variation could be caused by either a greater length of use of salbutamol by patients switching within pMDIs or a greater intensity of use, which may indicate increased severity of disease in the pMDI arm.

To test this second factor, the intensity of salbutamol use (measured in terms of prescriptions, items and total dose in both cohorts) was measured over the 12 months prior to the IE. There was a comparative paucity of use of salbutamol in both cohorts in the 12-month period prior to the switch. During the previous 12 months, 69.3% of patients switching to BAI (190 out of 274) and 65.8% of patients switching to a different pMDI (372 out of 565) had not received any prescriptions for salbutamol.

Thus, in both arms, approximately two-thirds of patients had not received any prescriptions for salbutamol in the 12 months prior to the switch. This may reflect the episodic nature of symptoms for these patients. However, both the mean number of items and the mean dose received over this previous 12-month period were almost double in the pMDI cohort than in the BAI cohort (0.58 compared with 1.17 items; 113 compared with 212 doses). Obviously, salbutamol prescriptions may not coincide with salbutamol usage, but they at least seemed to indicate a difference between the cohorts that required further investigation.

Results

Resource consumption

shows resource consumption in both patient cohorts in the 12-month period following the IE.

Table 2. Resource consumption in 12-month follow-up period.

In the 12-month period following the switch to BAI, an average of 1.78 prescriptions were issued covering 2.05 prescription items. In comparison, during the same period, the pMDI cohort received an average of 2.37 prescriptions covering 2.93 items. The total number of salbutamol doses required by patients in the BAI cohort was only 42% (246 vs. 587 doses) of that required by patients in the pMDI cohort, indicating either a significantly enhanced efficiency in use, significantly reduced wastage or significantly less severe patients in the BAI cohort.

A slightly greater proportion of patients in the BAI cohort required inhaled steroid use at some stage in the 12-month period following the IE (20 versus 16%). Analysis restricted to the patients requiring inhaled steroid use (n=55 for BAI and n=89 for pMDI) emphasised that the average dose required in both cohorts was equivalent. In contrast, patients in the BAI cohort had slightly fewer asthma consultations in the 12-month period (1.01 versus 1.11). However, one-quarter of the patients analysed were treated by practices that did not provide this information to the database. As such, the consultation analysis was based on only 634 of the total of 839 patients.

Prescription events occur when a prescription coincides with a clinic visit. This, therefore, excludes repeat prescriptions and indicates the need for the GP to actively manage the patient's condition. Such events were significantly lower in the BAI cohort, indicating less requirement for the patient to be actively managed by the GP.

The final column in adjusts the analysis for variations between the cohorts in age, sex, socioeconomic status and prior salbutamol use. To account for the impact of further potentially unknown confounders, the significance level for the analysis was intentionally set at a high level (p<0.001). Despite this, both the usage of salbutamol (whether measured in terms of prescriptions, items or doses) and prescription events were both found to be significantly lower in the BAI cohort.

provides details of the results obtained from the modelling analysis undertaken to assess the impact of BAI and pMDI on time to initiation of steroid use (i.e. the number of days elapsing between the IE and first prescription for an inhaled steroid).

Table 3. Time to first steroid use (since switch to pMDI or BAI).

Cost analysis

Mean total costs (including salbutamol consumption, asthma consultations and steroid consumption) in the BAI group was £45.39 vs. £41.91 in pMDI over the 12-month follow-up period (see )

Table 4. Mean costs by cohort and cost difference (£).

This estimated mean difference in total costs implies that BAI would require a 27.5% reduction in unit price (i.e. from the current weighted unit price of £6.25 to £4.23) to result in the same total costs to the primary care physician as pMDI.

Adjusting for sample heterogeneity

It is important to dichotomise the identified variation between systematic variations in the patient groups and the therapeutic advantages provided by either of the interventions. In order to achieve this, a regression analysis was undertaken which controlled for systematic variations between the cohorts in age, sex, socioeconomic status and prior salbutamol use. The aim of this analysis was to ‘wash away’ the effects of systematic differences between the cohorts to identify the underlying comparative therapeutic benefit provided by the inhalers. As previously indicated, only minor variations occurred in age, sex and socioeconomic status and, therefore, the main ‘driver’ of the regression adjustments was the lower pre-IE utilisation of salbutamol exhibited in the BAI cohort.

A linear regression model was used to adjust current doses of salbutamol and steroids to reflect variations in the prior dosage of salbutamol in both cohorts prior to the IE. Poisson models were used to adjust salbutamol prescriptions (adjusted for variations in the prior numbers of prescriptions) and salbutamol items (adjusted for variations in the prior number of items). Steroid prescriptions, asthma consultations and prescription opportunities were also adjusted for variations in the prior number of salbutamol prescriptions. Steroid use was analysed as a binary variable (yes or no) and was adjusted in line with the other regression analyses controlling for the prior number of salbutamol prescriptions.

The regression analysis also enabled significance tests to be applied to the difference between the two cohorts. The analysis identified variations that were highly significant (p<0.001) in a number of areas. Significantly fewer salbutamol prescriptions, items and total salbutamol doses were consumed by patients in the BAI cohort. In addition, significantly fewer adjustments by the GP in the therapeutic regimen (prescription opportunities) were apparent in the BAI cohort. Although the data indicated that the BAI cohort tended to make greater use of steroids and required lower numbers of asthma consultations, neither of these factors achieved statistical significance at the 5% level.

Patients at step 1 of the BTS/SIGN guidelines in asthma will vary significantly in terms of the intensity of their salbutamol use. Such variations provide one possible marker of the level of control of the symptoms related to their asthma. In order to analyse the comparative value of BAI versus pMDI in patients exhibiting different severities of asthma symptoms, the patient cohorts were stratified and separate analyses undertaken for patients who had received none, one, two, three and four salbutamol prescriptions or items in the 12 months prior to the IE. The majority of patients (67%) received no prescriptions of salbutamol, 16% received one prescription, 8% received two, 3% received three and only 2% received four prescriptions. As such, conclusions derived from the analyses of patient cohorts who receive two or more prescriptions of salbutamol in the 12 months prior to the IE have to be treated with caution due to the low patient numbers. The pattern of results identified is similar in all of the stratified analyses undertaken (see CitationTables 5–8).

Table 5. Additional number of prescriptions in BAI vs. pMDI in the 12-month period following switch – stratified analysis*.

Table 6. Additional number of items in BAI vs. pMDI in the 12-month period following switch – stratified analysis.

Table 7. Additional number of asthma consultations in BAI vs. pMDI in the 12-month period following switch – stratified analysis*.

Table 8. Additional number of prescription opportunities in BAI vs. pMDI in the 12-month period following switch – stratified analysis*.

In patients with none, one or two prescriptions of salbutamol in the previous 12 months, the additional therapeutic advantages of BAI over pMDI is emphasised. In the case of patients with none or one prior prescription of salbutamol, the differences between BAI and pMDI achieve statistical significance at the 5% level. However, as prior use of salbutamol increases to three or more prescriptions over the 12 months prior to the IE, the efficacy advantage seems to switch over in favour of pMDI. As previously stated, however, these latter results have to be treated with caution given the small numbers of patients analysed.

Discussion

This case study analyses resource use and clinical outcomes (time to initiation of steroid use) in the 12-month period following the switch of asthma patients to a different pMDI or BAI. Salbutamol use in the BAI cohort in the 12 months following the switch was only 42% of that in the pMDI cohort. Even when the analysis is adjusted for a number of potential confounders, the therapeutic advantage associated with a BAI, in terms of lower salbutamol, remains. The clinical implications of the enhanced steroid use in the BAI cohort is uncertain. Although there was little discernible effect on time to steroid use, a greater proportion of BAI patients (20 vs 16%) used inhaled steroids at some point in the 12 months following the switch. It is unlikely that this comparatively small increase in steroid use is responsible for the significant reduction in salbutamol use identified in BAI patients. However, for individual patients, the prescription of one steroid inhaler may abolish the use of salbutamol contributing towards the apparent cost effectiveness of BAI. BAI is associated with the additional costs of salbutamol items while resulting in lower costs from asthma consultations and a slight increase in costs of steroid consumption. However, the overall estimated mean difference in the costs at the primary care level implies that BAI would require a 27.5% reduction in unit price to achieve cost neutrality at the primary care level in comparison to the equivalent pMDI. The significantly reduced salbutamol dosage in the BAI cohort persists even when known systematic variations between the cohorts are taken into account through the regression analysis. This seems to indicate either enhanced efficiency or reduced wastage from the BAI. The authors readily acknowledge that a number of unknown confounding factors may still be affecting the results obtained. However, it is these very factors (compliance, ease of use, patient choice) that will crucially determine the comparative value of different inhalers in the real world clinical setting.

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this study was provided by an educational grant from Merck Respiratory (Generics UK) Ltd. Editorial control for this study rests with the lead author.

Notes

*Analysis by OLS using a lognormal transformation of the cost variable results in a signifi cant cohort difference p<0.001; thegeneralised linear model was preferred to the log linear one as the statistical distribution of the former is restricted to the positive range of the real line whereas the latter's is not. This analysis was based on the subset of patients for whom the number of asthma consultations was available (BAI: n=201; MDI: n=433).

References

- Jones V, Fernandez C, Diggory P A comparison of large volume spacer, breath-activated and dry powder inhalers in older people. Age and ageing 1999; 28: 481–484.1. Jones V, Fernandez C, Diggory P A comparison of large volume spacer, breath-activated and dry powder inhalers in older people. Age and ageing 1999; 28: 481–484.

- Lenny J, Innes J A, Crompton G K Inappropriate inhaler use: assessment of use and patient preference of seven inhalation devices. Respiratory Medicine 2000; 94: 496–500.2. Lenny J, Innes J A, Crompton G K Inappropriate inhaler use: assessment of use and patient preference of seven inhalation devices. Respiratory Medicine 2000; 94: 496–500.

- Price D, Pearce L, Powell S R et al. Handling and acceptability of the Easi-Breathe device compared with a conventional metered dose inhaler by patients and practice nurses. International Journal of Clinical Practice 1999; 53(1), 31–36.3. Price D, Pearce L, Powell S R et al. Handling and acceptability of the Easi-Breathe device compared with a conventional metered dose inhaler by patients and practice nurses. International Journal of Clinical Practice 1999; 53(1), 31–36.

- Shrestha M, Parupia H, Andrews B et al. Metered dose inhaler technique of patients in an urban ED: prevalence of incorrect technique and attempt at education. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 1996; 14(4), 380–384.4. Shrestha M, Parupia H, Andrews B et al. Metered dose inhaler technique of patients in an urban ED: prevalence of incorrect technique and attempt at education. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 1996; 14(4), 380–384.

- Cochrane M G, Bala M V, Downs K E et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for asthma therapy: patient compliance, devices and inhalation technique. Chest 2000; 117: 542–550.5. Cochrane M G, Bala M V, Downs K E et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for asthma therapy: patient compliance, devices and inhalation technique. Chest 2000; 117: 542–550.

- Kamps A WA, van Ewijk B, Jan Roorda R, Brand P L Poor inhalation technique, even after inhalation instructions in children with asthma. Pediatric Pulmonology 2000; 29(1), 39–42.6. Kamps A WA, van Ewijk B, Jan Roorda R, Brand P L Poor inhalation technique, even after inhalation instructions in children with asthma. Pediatric Pulmonology 2000; 29(1), 39–42.

- Scarfone R J, Capraro G A, Zorc J J et al. Demonstrated use of metered-dose inhalers and peak flow meters by children and adolescents with acute asthma exacerbations. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2002; 156: 378–383.7. Scarfone R J, Capraro G A, Zorc J J et al. Demonstrated use of metered-dose inhalers and peak flow meters by children and adolescents with acute asthma exacerbations. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2002; 156: 378–383.

- Luskin A T, Bukstein D, Ben-Joseph R The relationship between prescribed and delivered doses of inhaled corticosteroids in adult asthmatics. Journal of Asthma 2001; 38(8), 645–655.8. Luskin A T, Bukstein D, Ben-Joseph R The relationship between prescribed and delivered doses of inhaled corticosteroids in adult asthmatics. Journal of Asthma 2001; 38(8), 645–655.

- Tomlinson H S, Corlett S A, Allen M B, Chrystyn H Assessment of different methods of inhalation from salbutamol metered dose inhalers by urinary drug excretion and methacholine challenge. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2005; 60(6), 605–610.9. Tomlinson h S, Corlett S A, Allen M B, Chrystyn h Assessment of different methods of inhalation from salbutamol metered dose inhalers by urinary drug excretion and methacholine challenge. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2005; 60(6), 605–610.

- Giraud V, Roche N Misuse of corticosteroid metered-dose inhaler is associated with decreased asthma stability. European Respiratory Journal 2002; 19(2), 246–251.10. Giraud V, Roche N Misuse of corticosteroid metered-dose inhaler is associated with decreased asthma stability. European Respiratory Journal 2002; 19(2), 246–251.

- Lindgren S, Bake B, Larsson S Clinical consequences of inadequate inhalation technique in asthma therapy. European Journal of Respiratory Disease 1987; 70: 93–98.11. Lindgren S, Bake B, Larsson S Clinical consequences of inadequate inhalation technique in asthma therapy. European Journal of Respiratory Disease 1987; 70: 93–98.

- Price D, Thomas M, Mitchell G et al. Improvement of asthma control with a breath-actuated pressurised metered dose inhaler (BAI): a prescribing claims study of 5556 patients using a traditional pressurised metered dose inhaler (MID) or a breath-actuated device. Respiratory Medicine 2003; 97: 12–19.12. Price D, Thomas M, Mitchell G et al. Improvement of asthma control with a breath-actuated pressurised metered dose inhaler (BAI): a prescribing claims study of 5556 patients using a traditional pressurised metered dose inhaler (MID) or a breath-actuated device. Respiratory Medicine 2003; 97: 12–19.

- Kelloway J S, Wyatt R A Cost-effectiveness analysis of breath-actuated metered dose inhalers. Managed Care Interface 1997; 10(9), 99–107.13. Kelloway J S, Wyatt R A Cost-effectiveness analysis of breath-actuated metered dose inhalers. Managed Care Interface 1997; 10(9), 99–107.

- Langley P C The technology of metered-dose inhalers and treatment. Clinical Therapeutics 1999; 21(1), 236–253.14. Langley P C The technology of metered-dose inhalers and treatment. Clinical Therapeutics 1999; 21(1), 236–253.

- Haycox A, Mitchell G, Niziol C et al. Cost effectiveness of asthma treatment with a breath-actuated pressurised metered dose inhaler (BAI) – a prescribing claims study of 1856 patients using a traditional pressurised metered dose inhaler (MDI) or a breath-actuated device. Journal of Medical Economics 2002; 5: 65–77.15. Haycox A, Mitchell G, Niziol C et al. Cost effectiveness of asthma treatment with a breath-actuated pressurised metered dose inhaler (BAI) – a prescribing claims study of 1856 patients using a traditional pressurised metered dose inhaler (MDI) or a breath-actuated device. Journal of Medical Economics 2002; 5: 65–77.

- British Thoracic Society, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines NetworkBritish guideline on the management of asthma. Thorax 2003; 58(1), i1–i94.16. British Thoracic Society, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network British guideline on the management of asthma. Thorax 2003; 58(1), i1–i94.

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Asthma management and prevention. NHLBI, NIH Bathesda, Maryland. 1995; publication 96-3659A..17. , Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Asthma management and prevention. NHLBI, NIH Bathesda, Maryland. 1995; publication 96-3659A..

- CACI, http://www.caci.co.uk18. CACI, http://www.caci.co.uk

- Lewis M, Patwell J, Briesacker B The role of insurance claims databases in drug therapy outcomes research. Pharmacoeconomics 1993; 4: 323–330.19. Lewis M, Patwell J, Briesacker B The role of insurance claims databases in drug therapy outcomes research. Pharmacoeconomics 1993; 4: 323–330.

- Sackett D Bias in analytical research. Journal of Chronic Disease 1979; 32: 51–63.20. Sackett D Bias in analytical research. Journal of Chronic Disease 1979; 32: 51–63.

- Green S, Byar D Using observational data from registries to compare treatment: the fallacy of omnimetrics. Statistics in Medicine 1984; 3: 361–370.21. Green S, Byar D Using observational data from registries to compare treatment: the fallacy of omnimetrics. Statistics in Medicine 1984; 3: 361–370.

- Curtis L, Netten A Unit Costs of Health and Social Care. Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, Canterbury, 2002.22. Curtis L, Netten A Unit Costs of Health and Social Care. Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, Canterbury, 2002.

- Categories of ACORN, http://caci.co.uk/acorn23. Categories of ACORN, http://caci.co.uk/acorn