Abstract

Objective: To examine hospitalisation rates and resource utilisation following initiation of risperidone long-acting therapy (RLAT) among US veterans with schizophrenia.

Methods: Encounter data were analysed from the Ohio Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System. Adult patients (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder) with ≥1 medical or hospital visits with a diagnosis code of 295.xx, continuous enrolment from January 2003 through January 2006, and ≥4 injections of RLAT were selected. Analyses compared psychiatric-related resource utilisation pre- and post-exposure to RLAT; each patient served as his/her own control. The pre-exposure and post-exposure periods defined were equal in duration (e.g., a 6-month post-exposure period was matched with a 6-month pre-exposure period). Descriptive and comparative analyses (paired t tests, McNemar's test) were performed.

Results: Patients (n=106) were 51.9 years old (±10.2), male (93%), white (73%) and received on average 14 RLAT doses (±9.7; range, 4–47 injections) over 309 days (±196; range, 42–737 days). Most experienced a psychiatric-related hospitalisation prior to initiation; less than half experienced hospitalisation after initiation (75% vs. 42%; p<0.001). Relative to pre-initiation, fewer psychiatric-related hospitalisations (mean [SD] change, –0.8 [2.0]; p<0.001), shorter length of stay (–25 [63.6] days; p<0.001), fewer inpatient days/month (–3.1 [7.2] days) and one (2.8) additional outpatient visit/month (p<0.001) occurred post-initiation.

Limitations: The absence of a control group in this pre-/post comparison may have resulted in exposure to a regression to the mean effect. Also, this study evaluated only one cohort of patients in a VA healthcare setting.

Conclusions: VA patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder treated with RLAT experienced fewer hospitalisations and psychiatric-related inpatient days following RLAT initiation. Further studies utilising a control group and in non-VA populations are warranted.

Introduction

With the emergence of newer antipsychotic agents (atypicals), providers can select from a wider array of safe, effective and well-tolerated oral treatment alternatives for their patients with schizophrenia disorders. The persistent and cyclical nature of schizophrenia can present treatment adherence challenges, often subverting the achievement of intended patient benefit. For example, missed doses of oral medications can go undetected for extended periods, resulting in increased crisis contacts, hospitalisations and other indicators of disease relapse. However, treatment strategies that promote adherence can lead to improved patient outcomes through preventing or delaying disease relapseCitation1. In a healthcare decision-making environment increasingly focused on identifying an appropriate balance between established patient benefit and cost of treatment, information on the outcomes and costs of new treatment options is central to maximising positive outcomes for patients.

Long-acting injectable agents provide a more immediate basis for assessment of decreased adherence than an oral treatment regimen. In addition, the pharmacokinetics of long-acting agents provide an efficacious drug plasma concentration over time. As such, long-acting preparations offer an option to treatment success, particularly for patients with known or anticipated treatment adherence issues. Risperidone long-acting therapy (RLAT) is the first long-acting injectable formulation of an atypical antipsychotic drug with demonstrated efficacy and tolerability as well as a decrease in hospitalisation in patients with schizophreniaCitation2–6. Additionally, economic models suggest that RLAT is a viable therapy based on effectiveness, tolerability and cost savingsCitation7–9.

Although the findings from previous international studies indicate a positive impact of RLAT on relapse, hospitalisation, clinical outcomes and costs, research demonstrating the impact of RLAT on similar outcomes in a US-based population has been lacking. The current analysis was designed to address a portion of this gap in the literature. The primary purpose of this study was to examine hospitalisation and economic outcomes in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder prior to and following initiation of RLAT within the Ohio Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System setting.

Patients and methods

Veterans Integrated Service Network 10 Database

Data for the study were obtained from the Ohio VA Healthcare System. The Veterans Integrated Service Network 10 (VISN 10) database is a closed system that contains electronic healthcare records of patients for all five VA hospitals in Ohio, including all pharmacy, inpatient and outpatient encounters in the VA system. Each encounter and prescription has an associated cost. The Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) was used; this integrated system of software applications directly supports patient care at Veterans Health Administration (VHA) healthcare facilities and operates under the auspices of the VHA Office of Information.

Each VistA application generates at least one data file. Within these files are the clinical, administrative and computer infrastructure-related data that support day-to-day operations and contain patients’ medical and healthcare utilisation histories (including data on demographics, episodes of care, medicines, practitioner information, diagnoses and procedures). All patients treated at VA Medical Centres (VAMCs) are included in the files, which are updated continually at the point of care or as part of administrative processes. Data are entered into VistA by manual entry, bar codes and automated instrumentation. Some data are derived from central financial, personnel and operational systems and distributed to local facilities’ VistA files. These files include information on all persons treated at a VAMC, across the full spectrum of inpatient and outpatient care provided at that facility, and they provide the most clinical detail of any VA database. Within the VistA system, each active patient is assigned an integration control number (ICN) as a unique identifier. Institutional review board approval was obtained through the Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC.

Study sample

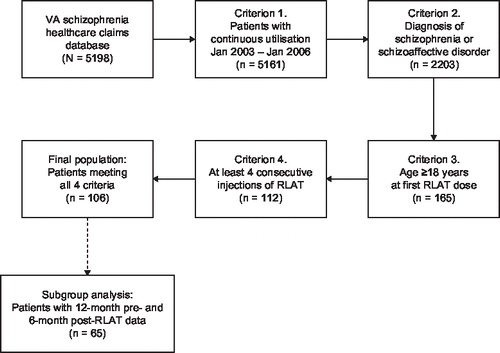

Healthcare encounter data were retained for patients who met four a priori eligibility criteria: (1) had 3 years of continuous enrolment (January 2003 through January 2006), (2) carried a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (ICD–9–CM; 295.xx) at any time from 2003 to 2006, (3) were aged 18 years or older, and (4) had received a minimum of four doses of RLAT. RLAT is administered as one injection every 2 weeks; the four-dose minimum that was chosen reflects steady-state concentrations for RLAT. This resulted in a final study sample of 106 adult patients who met all four eligibility requirements for study inclusion () (note: FDA approved RLAT in October 2003). From this study population, a subgroup analysis was also performed for patients who had 6 months of data following initiation of RLAT and 12 months of data prior to initiation of RLAT.

Analysis approach

The primary goal of the analysis was to compare the proportion of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder experiencing psychiatric-related hospitalisations pre- and post-initiation of RLAT. The secondary objectives were to assess various measures of resource utilisation and costs pre- and post-initiation of RLAT.

An intent-to-treat approach was used in these analyses; the index anchor was established by each patient's initiation on RLAT. During the study period of January 1, 2003, through January 1, 2006, the index date that started the post-RLAT period (post-index) was defined as the date of first injection with RLAT for outpatients, or as the first day after hospital discharge for patients initiated with RLAT as inpatients. The end of the post-RLAT period was defined as the last day of the enrolment period (January 2006) or earlier when a patient discontinued eligibility in the VISN 10 system.

The pre-RLAT period was defined as the time immediately prior to initiation with RLAT (index) that was equal in duration to the post-RLAT period. Therefore, each patient contributed a different amount of time, but each patient's pre- and post-RLAT periods were equivalent. For example, a patient whose first injection was on March 1, 2003, and who had 2 months of pre-injection enrolment had a 2-month post-injection period from March 1, 2003, through May 1, 2003. For a patient whose first injection was on March 1, 2004, and who had 14 months of pre-injection enrolment, the post-injection period was 14 months beginning on March 1, 2004.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of interest in these analyses was the mean number of psychiatric-related hospital admissions. In addition, a set of psychiatric-related resource utilisation, compliance and cost measures were investigated. The secondary measures included the number of hospital days; the mean number of hospital days per month; the mean number of outpatient visits, medication compliance and persistence; and the mean monthly costs associated with inpatient, outpatient, prescription and total (medical and prescription) costs. Costs were taken directly from the claims data and calculated on a patient level for medications, hospitalisations and outpatient visits as an average monthly cost pre- and post-RLAT.

Psychiatric-related hospitalisation was defined as an admission to an inpatient unit for psychiatric reasons. The assignment of the hospitalisation to a study period (i.e., pre- or post-RLAT) was based on the relationship of admission date to the index date for each patient. If RLAT was initiated during a hospital admission, the hospitalisation was counted in the pre-RLAT period (i.e., the end date of the hospital stay was the index date).

Length of stay for all hospital admissions was calculated as the number of days between hospital admission and discharge. The entire length of stay during which RLAT was initiated was counted in the pre-RLAT period. Hospital days that occurred outside of the study periods were censored from analysis.

Medication compliance pre- and post-RLAT based on patients was measured based on subjects in the primary study population. This analysis assumed that patients received at least three antipsychotics per period as designed by Weiden et al Citation10. Compliance was calculated using the medication possession ratio (MPR) of antipsychotic therapy, calculated as follows: days’ supply for all but the last medication claim/(total number of days between first and last medication claim – number of inpatient hospital days). A 14-day supply was assumed for all RLAT prescriptions. Additional measures of medication compliance included:

| 1. | Medication consistency – the percentage of time a patient appears to have medication available divided by the period during which the patient should theoretically have used all of the available medication. Consistency was calculated as days of supply of medication in the study period/time of study period. | ||||

| 2. | Medication persistence – the time from the initiation to discontinuation of therapy expressed as a proportion of the study period. This is calculated as the number of days between the first and last prescription divided by the fixed number of days in the study period. | ||||

| 3. | Medication gap – the longest period during which no medication appeared to be available, starting from the initiation date through the end of the study period. Contiguous periods in which no medication appeared to be available were based on dispensing date and recorded days of supply for each antipsychotic prescription. No limit was applied to this gap. | ||||

Analyses

Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics, paired t-tests to compare psychiatric-related hospitalisations during the pre- and post-RLAT periods, and McNemar's test to compare the study proportions. Owing to the exploratory nature of this research, no corrections for multiple comparisons and multiplicity were made for tests of significance. Differences in cost categories approximated a normal distribution; therefore, standard parametric tests were used on the difference in costs between groups.

Results

Sample description

Patients (n=106) were 51.9 years of age (±10.2; range, 30–85 years) and the majority were male (93%). Of those for whom information on race was available (n=84), the majority were white and non-Hispanic (73%). The most common psychotropic medications used by patients in the pre-RLAT period were antipsychotics (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine) and mood stabilisers (divalproex, trazodone); a small proportion (19.8%; n=21) used multiple antipsychotics. The mean daily doses of the medications were found to be consistent with labelling indications for each of the agents ().

Table 1. Summary of mean daily doses of atypical antipsychotics pre-RLAT*

A small proportion of patients (13%) received their first dose of RLAT during an inpatient admission. Throughout the study window, patients received an average of 14 RLAT doses (±9.7; range, 4–47 injections) over a period of 309 days (±196; range, 42–737 days). The average starting dose for RLAT was 29.2 mg (±7.9 mg; median, 25 mg) and the average last dose was 35.5 mg (±10.4 mg; median, 37.5 mg). The average injection interval was 24 days (±13.2 days; median, 19.8). The percentages of patients started on RLAT 25 mg, 37.5 mg and 50 mg were 75%, 17% and 9%, respectively. The percentages of patients ending on RLAT 25 mg, 37.5 mg and 50 mg were 43%, 29% and 27%, respectively.

Among patients with an RLAT dose increase (n=44), the average time to first RLAT dose increase was 4.3 months (±3.8; median, 2.8 months). In all, 60 patients (57%) received supplemental oral atypical antipsychotics beyond 3 weeks (mean duration, 189 days).

Primary outcome measure – psychiatric-related hospitalisations

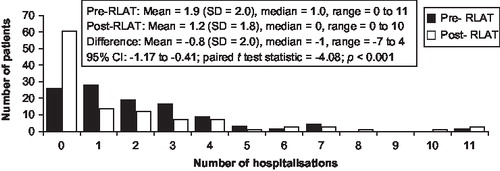

The percentage of patients experiencing one or more psychiatric-related hospitalisations was significantly lower in the post-RLAT period than in the pre-RLAT period (42% [45/106] vs. 75% [80/106], p<0.001; ). The percentage of patients experiencing two or more psychiatric-related hospitalisations was significantly lower in the post-RLAT period than in the pre-RLAT period (29% [31/106] vs. 50% [53/106], p<0.001; ).

Table 2a. McNemar's test of (a) ≥1.

Table 2b. McNemar's test of (b) ≥2 psychiatric-related inpatient episodes.

Secondary outcomes measures – resource utilisation

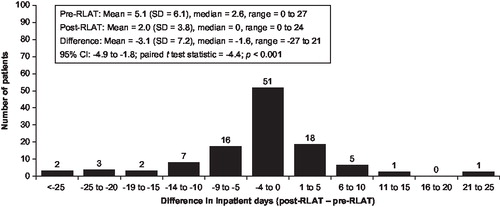

In addition to the reduction in the proportion of persons experiencing a hospitalisation in the post-initiation period, the length of stay decreased. The mean number of psychiatric-related hospitalisations was reduced from 1.9 to 1.2, a mean (SD) decrease of 0.8 (2.0; p<0.001; ); and the total number of psychiatric-related inpatient hospital days decreased from 45 to 20 days (mean [SD] change, –25 [63.6] days; p<0.001). The number of psychiatric-related inpatient hospital days per month also declined from 5.1 in the pre-RLAT period to 2.0 in the post-RLAT period (–3.1 [7.2]; p<0.0001; ). A slight increase in the number of psychiatric-related outpatient visits was noted (mean [SD] change 1.0 [2.8] visit; p<0.001).

Compliance and persistence

A total of 69 patients in the original population used at least three antipsychotics during the pre- and post-injection periods and were included in the compliance and persistence analysis. In this group, patients demonstrated greater compliance with their medication after RLAT therapy was prescribed, as measured by the MPR (p=0.016) and medication persistence (p<0.001) (). Sensitivity analysis showed these results to be significant when limiting the analysis to patients with two or more antipsychotic prescriptions per period, but not when limiting the analysis to patients with four or more and five or more antipsychotic prescriptions per study period.

Table 3. Compliance comparisons pre- and post-RLAT treatment (n=69)*.

VA costs

From the pre- to post-injection periods, there was a $356 mean (SD, $214) increase in monthly psychiatric-related medication costs (p<0.001), a $2273 mean (SD, $5450) decrease in monthly hospitalisation costs (p<0.001), a $320 mean (SD, $1355) increase in monthly outpatient visit costs (p=0.02) and a $1598 mean (SD, $6049) decrease in total monthly costs (p=0.008; ).

Table 4. Comparison of average monthly VA costs per patient (US $) by study period for different cost components (n=106).

Subgroup analysis of patients with 6 months of post-RLAT data

Of the 106 patients in the primary analysis, 65 (61.3%) had 6 months of post-RLAT data and 12 months of pre-RLAT data. Baseline demographics were similar to the original study population. The percentage of patients experiencing one or more hospitalisations was significantly lower in the post-RLAT compared with the pre-RLAT periods (32% [n=21] vs. 63% [n=41]; p<0.001). The percentage of patients experiencing two or more hospitalisations was also significantly lower in the post-RLAT compared with the pre-RLAT period (17% [n=11] vs. 45% [n=29], p<0.001).

The number of psychiatric-related hospitalisations was reduced from 1.5 to 0.9, a mean (SD) decrease of 0.9 (1.6; p<0.001); and the total number of psychiatric-related inpatient hospital days decreased from 39 to 9 days (mean [SD] change, –30 [56.6] days; p<0.001). The number of psychiatric-related inpatient hospital days per month also declined from 3.1 in the pre-RLAT period to 1.5 in the post-RLAT period (–1.6 [6.2]; p=0.037), but the number of psychiatric-related outpatient visits increased (mean [SD] change 3.3 [3.4] visit; p<0.001).

Discussion

In this study, a cohort of VA patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder who were treated with RLAT experienced positive outcomes in resources use (reduced hospitalisation and length of stay) and improved medication compliance. Additionally, the overall costs of care were significantly lower following RLAT initiation in these patients. The results from the original study population were similar to those for a subgroup population of patients who had 6 months of follow-up after initiation of RLAT. The positive outcomes associated with RLAT in this study stand in contrast to those reported by Hosalli and DavisCitation16 but mirror findings of more recent studies. Taylor et al Citation17 observed improved outcomes for patients followed over a 6-month period, and Muirhead et al Citation18 observed fewer crisis and hospitalisation events among RLAT patients.

The role of medication management in a cyclical and often negatively spiralling condition such as schizophrenia is well accepted. Patients who are at risk for or who experience interruptions or inconsistency in medication treatment course present specific treatment challenges for providersCitation19. Often these patients interface with the healthcare system in emergent and high-intensity venues. The course of treatment for many patients could be positively impacted through the use of a safe, effective and well-tolerated long-acting atypical agentCitation20,21.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the absence of a control group. Utilising a pre-/post comparison without a control group exposes one to a regression to the mean effect. An assumption that adherence is positively impacted by utilising long-acting dosage forms of antipsychotics has not been shown in a randomised clinical trial. Although it is standard practice in pharmacoeconomic studies to provide comparison with alternative treatments, no such comparisons were made in these analyses because an equivalent comparator is not available. Additionally, this study evaluated only a single cohort of patients in a VA healthcare setting. The extent to which these results can be applied outside the VA healthcare system is limited. Comparison with an oral antipsychotic treatment cohort was not pursued, as it was expected the VA patient population being treated with RLAT would differ from individuals treated with an oral antipsychotic.

Although a comparative analysis is warranted to confirm these results, these data are similar to an analysis of a large-scale observational electronic database known as the Schizophrenia Treatment Adherence Registry (eSTAR). These studies (24-month duration) examined medical records of subjects who switched to RLAT from oral antipsychotics (including risperidone) and compared them with subjects who remained on oral antipsychotics. In these analyses, subjects who switched to RLAT from oral antipsychotics had higher treatment retention and larger reductions in mean length of hospital stay and mean number of hospital stays compared with subjects who continued oral antipsychotics and appeared to be more cost effectiveCitation22–24.

Our analyses evaluated only VA patients who used four or more RLAT doses and did not include VA patients with more limited exposure to RLAT. The cut-off criteria were based on clinical study results indicating evidence of stable plasma concentration after the third injection and steady-state concentration of the active moiety after the fourth injectionCitation25. Safety and efficacy of RLAT have been previously established and were not specifically evaluated in this cohort of VA patients. Resource utilisation and costs were defined as costs incurred during the observation window for each person.

Conclusions

The results observed in this study indicate that VA patients may experience positive outcomes following the initiation of RLAT. Future research should include a control group, appropriate utilisation of supplemental oral atypical antipsychotics, dosing strategies, and general clinical and safety outcomes related to initiation of RLAT therapy.

Acknowledgements

Declarations of interest: This research was sponsored by Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. M. F. has disclosed that he is a consultant for Ortho-McNeil Janssen and other pharmaceutical companies, and was a member of the speakers’ boards for Ortho-McNeil Janssen and other pharmaceutical companies. K. S. and M. S. have no relevant financial relationships to disclose. P. R. has disclosed that she was a consultant for Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC on this manuscript. R. D. has disclosed that he is a current employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and a J&J stockholder. S.V. and S. F. have disclosed that they were employees of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, when this analysis was performed. The authors wish to acknowledge the technical and editorial support provided by Matthew Grzywacz, PhD and Helix Medical Communications.

Notes

References

- McEvoy JP. Risks versus benefits of different types of long-acting injectable antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(Suppl 5):15-18.

- Kane JM, Eerdekens M, Lindenmayer JP, Long-acting injectable risperidone: efficacy and safety of the first long-acting atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1125-32.

- Fleischhacker WW, Eerdekens M, Karcher K, Treatment of schizophrenia with long-acting injectable risperidone: a 12-month, open-label trial of the first long-acting second-generation antipsychotic. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:1250-7.

- Simpson GM, Mahmoud RA, Lasser RA, A 1-year double-blind study of 2 doses of long-acting risperidone in stable patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;67:1194-203.

- Locklear J, Lasser R, Zhu Y, Hospitalization during long-term treatment with long acting risperidone. Poster presented at: 2004 Institute on Psychiatric Services’ Scientific Program, October 6-10, 2004, Atlanta, GA.

- Llorca P-M, Devos E, Eerdekens M, Re-hospitalization rates with long-acting risperidone are lower than those reported for other antipsychotics. Poster presented at: the XXII Biennial Meeting of the Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologium, June 23-27, 2002, Montreal, Canada.

- Haycox A. Pharmacoeconomics of long-acting risperidone: results and validity of cost-effectiveness models. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23(Suppl 1):3-16.

- Edwards NC, Locklear JC, Rupnow MF, Cost effectiveness of long-acting risperidone injection versus alternative antipsychotic agents in patients with schizophrenia in the USA. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23(Suppl 1):75-89.

- Chue PS, Heeg B, Buskens E, Modeling the impact of compliance on the costs and effects of long-acting risperidone in Canada. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23(Suppl 1):62-74.

- Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Groqq A, Partial compliance and risk rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:886-91.

- ABILIFY (aripiprazole) [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Rockville, MD: Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc., 2007.

- ZYPREXA (olanzapine) [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company, 2007.

- SEROQUEL (quetiapine) [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca, 2007.

- RISPERIDAL (risperidone) [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen, LP, 2007.

- GEODON (ziprasidone) [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer, Inc., 2007.

- Hosalli P, Davis JM. Depot risperidone for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;4:CD004161.

- Taylor DM, Young CL, Mace S, Early clinical experience with risperidone long-acting injection: a prospective, 6-month follow-up of 100 patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:1076-83.

- Muirhead D, Harvey C, Ingram G. Effectiveness of community treatment orders for treatment of schizophrenia with oral or depot antipsychotic medication: clinical outcomes. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006;40:595-605.

- Byerly MJ, Nakonezny PA, Lescouflair E. Antipsychotic medication adherence in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2007;30: 437-52.

- Kane JM. Strategies for improving compliance in treatment of schizophrenia by using a long-acting formulation of an antipsychotic: clinical studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(Suppl 16):34-40.

- Keith SJ, Kane JM. Partial compliance and patient consequences in schizophrenia: our patients can do better. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:1308-15.

- Olivares JM, Rodriguez-Martinez A, et al; e-STAR Study Group. Cost-effectiveness analysis of switching antipsychotic medication to long-acting injectable risperidone in patients with schizophrenia: a 12- and 24-month follow-up from the e-STAR database in Spain. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2008;6:41-53.

- Olivares JM, Peuskens J, Pecenak J, Clinical and resource-use outcomes of risperidone long-acting injection in recent and long-term diagnosed schizophrenia patients: results from a multinational electronic registry. Curr Med Res Opin 2009; Jul 15 [Epub ahead of print].

- Olivares JM, Rodriguez-Morales A, Diels J, Long-term outcomes in patients with schizophrenia treated with risperidone long-acting injection or oral antipsychotics in Spain: results from the electronic Schizophrenia Treatment Adherence Registry (e-STAR). Eur Psychiatry 2009;24:287-96.

- Gefvert O, Eriksson B, Persson P, Pharmacokinetics and D2 receptor occupancy of long-acting injectable risperidone (Risperdal Consta) in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2005;8:27-36.