Abstract

Objective: To estimate the clinical outcomes and costs associated with reconfiguring the management of TIA in the UK to offer patients rapid access to outpatient clinics for specialist assessment and treatment.

Methods: An economic deterministic model was run comparing two pathways – one arm representing current clinical care based on national guidelines and clinical practice and patient referral to a weekly outpatient clinic, and a revised care pathway replicating phase 2 of the EXPRESS study with patient referral to a daily outpatient clinic. The outcomes of the model were measured in terms of recurrent strokes avoided and net budget impact to secondary care.

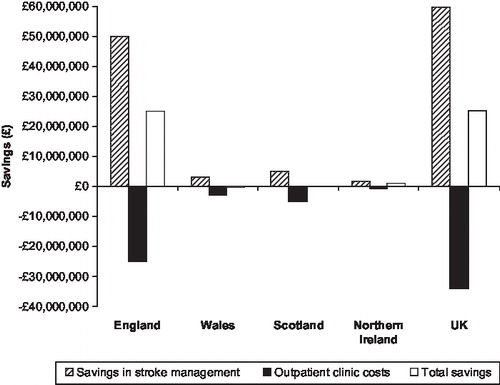

Results: Reconfiguring TIA care pathways in the UK could result in the avoidance of 8,164 recurrent stroke events. The model predicts savings of £25,573,279 for the UK healthcare system over 12 months. Annual net savings are predicted in England (£24,916,011), Scotland (£80,554) and Northern Ireland (£1,041,817). In Wales, increased costs of £450,435 are estimated.

Limitations: Using the data published from the EXPRESS study, it is not possible to model a stepwise approach to implementing the revised TIA care pathway. It is therefore assumed that it would be possible to implement the revised TIA care pathway as detailed in the EXPRESS study across the UK and achieve the reduction in recurrent stroke risk that was reported.

Conclusions: The model suggests that the reconfiguration of TIA care pathways in the UK to offer rapid access to treatment and assessment could prevent TIA-related future stroke events and potentially result in cost savings to the healthcare system.

Introduction

It is recognised that in the acute period following a transient ischaemic attack (TIA), patients are at considerable risk of a strokeCitation1. Despite this, the provision of TIA care in the UK is currently variable; weekly TIA outpatient clinics are not offered in all regions and more than half of all patients will wait more than 14 days to be assessed and treatedCitation2,3. During this time they may be at risk of experiencing a stroke – a 2004 study reported that in the week following a TIA, 8% of patients experienced a strokeCitation1.

The recent Early use of eXisting PREventative Strategies for Stroke (EXPRESS) study analysed the impact of introducing rapid assessment and treatment for patients suffering TIA or minor strokeCitation2. The prospective study was nested within the ongoing Oxford Vascular Study (OXVASC) and split into two sequential phases. In phase 1 patients presenting to their GP with suspected TIA or minor stroke were referred to a daily, appointment-based outpatient clinic. Following assessment at the clinic, treatment recommendations were faxed to the referring primary care physicians, and patients instructed to contact them as soon as possible. Patients typically experienced a 3-day delay between first event and specialist assessment, which the authors acknowledged was not representative of current care in the UK where a 14 day delay is typicalCitation3. In phase 2, patients with suspected TIA or minor stroke were sent directly to the outpatient clinic by their GP; no appointment was necessary, and treatment was initiated immediately in the clinic if the diagnosis was confirmed. The 90-day risk for recurrent stroke in the TIA population (including those referred to the outpatient clinic and those treated entirely in primary care) was 4.4% in phase 2 – reduced from 12.4% in phase 1 – demonstrating that a greater focus on early, effective management of TIA could have a significant impact on subsequent stroke rates. The authors suggested that adoption of the phase 2 care pathway nationwide could be associated with the prevention of 10,000 recurrent strokes annually following TIA or minor strokeCitation2. A follow-up publication estimated that this would be associated with savings of 290,000 hospital bed-days and £68 million in acute care costsCitation3. However, the costs to the health service that would be associated with establishing rapid-access specialist outpatient clinics were not quantifiedCitation3. In light of this, the authors carried out an evaluation to compare the clinical outcomes and cost to the health service of the care pathway outlined in phase 2 of the EXPRESS study with the current UK care pathway for patients experiencing a TIA.

A deterministic model was developed that compared two care pathways – one arm representing existing clinical practice based on national clinical guidelines and estimates of current clinical practiceCitation5,6 where patients were assumed to be referred to a weekly outpatient clinic, and a revised care pathway that replicated the treatment protocols of phase 2 of the EXPRESS study. The outcomes of the model were measured in terms of recurrent strokes avoided and net budget impact to secondary care.

Methods

A deterministic model evaluated a current care pathway and a proposed revised care pathway for patients experiencing TIA over 1 year from a NHS perspective. Although NHS budgets are typically planned over 3 years, a 1-year time frame was used for clarity. It is expected that any clinical benefits associated with the revised care pathway would likely be seen within 90 days of the initial TIA event and would therefore be realised within the 1-year model time frame.

All costs were in GBP and standardised to 2007–2008 prices by use of the NHS hospital and community health services inflation indexCitation4. Given the 1-year time frame of the model no discounting rate was applied.

TIA care pathways

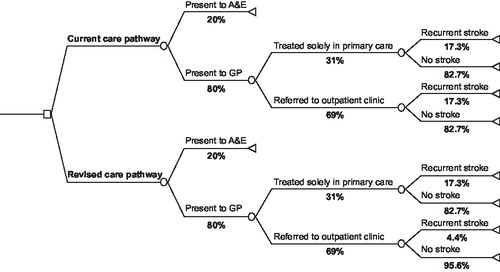

The model consisted of a current care and a revised care pathway. Each care pathway considered the number of TIA patients who presented to their GP, the proportion of these who were referred to the outpatient clinic, the outpatient clinic costs, the risk of TIA-related recurrent stroke and the cost of managing clinical outcomes (). Care given in the outpatient clinic in the current care pathway represented existing practice based on national clinical guidelines and estimates of current clinical practiceCitation5,6. The care provided by the outpatient clinic in the revised care pathway was based on the treatment protocols set out in phase 2 of the EXPRESS studyCitation2.

Table 1. Default inputs.

The number of patients experiencing TIA was calculated using an assumed annual TIA incidence of 0.19% (as reported by Gibbs et al 2001Citation7) for the given population in each model scenario. Patients experiencing a TIA were assumed to either present to their GP or directly to A&E (). Of the patients who presented to their GP, it was assumed 69% were referred to the weekly outpatient clinic, while 31% of patients were assumed to be treated solely in primary care. This is based on the referral rate reported in the EXPRESS studyCitation2. Subsequently, only patients who presented to primary care following a TIA were included in the model. Patients who presented directly to secondary care were excluded from the model as it was assumed that their care pathway would not be altered by changes in the availability of the outpatient clinic.

Figure 1. Care pathway overview. This figure is an illustrative diagram of the patient flow through the model. The difference between the current and the revised care pathways is given by: where NCLINIC is the number of clinics, STAFF the staffing costs per clinic, PATCOST the combined medical and diagnostic cost per patient, PATCLINIC the average number of patients visiting each clinic, TIAGP the number of TIA patients presenting to their GP, 0.089 the differential in the risk of stroke between the two model arms (assuming a 69% referral rate) and STROKECOST the cost of stroke.

All TIA patients in the current care pathway were assumed to have a 90-day risk of recurrent stroke of 17.3%, as reported by Coull et al 2004Citation1. This figure is taken from a prospective cohort study of patients experiencing TIA who presented either to their GP or secondary care. It is noted that in reality there may be a differential risk of recurrent stroke depending on where a patient presents, however these data were not available. The 90-day risk of recurrent stroke for patients experiencing TIA who were referred to the phase 2 outpatient clinic in the EXPRESS study was not reported in the original publication. Therefore the total study population 90-day risk of 4.4% – reported in the entire TIA population in phase 2 of the EXPRESS study - was used for the revised care pathwayCitation2. This assumption is conservative as the rate of recurrent stroke would be expected to be lower in those referred to the outpatient clinic than those treated entirely in primary care. Patients who were treated entirely in primary care in the revised care pathway (i.e. not referred to the outpatient clinic) were assumed to experience the same risk of recurrent stroke as patients in the current care pathway (i.e. 17.3%). Although the risk of recurrent stroke is greatest in the first week after a TIA, this risk remains over an extended time-frame. It is therefore considered reasonable that stroke risk was measured in terms of the 90-day risk of stroke as reported in the EXPRESS studyCitation2.

The secondary care cost of managing each acute stroke event was assumed to be £7,306.67 (inflated from the 2004–2005 cost). This is the cost reported in a population-based study by Luengo-Fernandez et al of 346 patients, who had either a first-ever or recurrent stroke during the study period. The study determined the initial secondary care cost of acute stroke in the UK from a NHS perspective, including hospitalisation, subsequent length of stay and acute care costsCitation8. This value was used in both care pathways as it was assumed that changes in TIA management would not affect either the severity of recurrent stroke or provision of care given for one.

Outpatient clinic costs

The outpatient clinic costs comprised medication, diagnostic testing and staffing costs. Medication and diagnostic test costs were calculated on a per patient basis; staffing costs were calculated on a per clinic basis.

How medications are handled may vary across the UK, with treatments initiated following a TIA being prescribed either by primary care practitioners or in the outpatient clinic. It was therefore conservatively assumed that the outpatient clinic in the current care pathway would not incur any medication costs. For the revised care pathway, based on phase 2 of the EXPRESS study, drug costs were included for 4-week courses of antiplatelet, anticoagulant and blood pressure lowering medications issued in the outpatient clinic. Prescription rates were based on those reported in phase 2 of the EXPRESS studyCitation2. A one-off 300 mg dose of aspirin given immediately to every patient upon arrival at the outpatient clinic in phase 2 of the EXPRESS study was also taken into considerationCitation2. The cost of the medications were taken from the British National FormularyCitation9.

To reflect current clinical practice, the diagnostic tests performed at the outpatient clinic in the current care pathway were based on the NHS Implementing the National Stroke Strategy imaging guideCitation5. This states that approximately 50% of suspected TIA patients require a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan and 80% will require scanning of the arteries around the throat (patients were assumed to receive a Doppler ultrasound).

Diagnostic tests performed in the outpatient clinic in the revised care pathway were based upon phase 2 of the EXPRESS study, where all patients received a computerised tomography (CT) scan, Doppler ultrasound and electrocardiogram (ECG)Citation2. Patients were also assumed to receive a blood test upon arrival at the outpatient clinic in both the current and the revised care pathways. The cost of all diagnostic tests were taken from the NHS reference costsCitation10.

The staff in the outpatient clinic for both care pathways were assumed to consist of a neurologist, two nurses, two radiologists, a sonographer and a hospital porter. Staff in the current care pathway were assumed to work in a weekly half-day clinic for 4 hours a weekCitation2. In the revised care pathway, staff were assumed to work in a Monday to Friday half-day outpatient clinic for 20 hours a weekCitation2. In the absence of other data, the hourly rate for the hospital porter was taken from the NHS careers websiteCitation11; the hourly rates for all other staff members were taken from the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU)Citation4.

It was assumed within the model that space for an outpatient clinic would be available for daily use. Building overhead costs such as rent and amenities were therefore not included.

Scenarios

The model was run with five different scenarios to estimate the impact of reconfiguring the TIA care pathway for the populations of England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the UK as a whole. It was assumed that, on average, each Primary Care Trust (PCT)/Council Board/Health Board would require one outpatient clinic to service the local population. Therefore, the number of clinics for each scenario was 152 for England, 22 for Wales, 32 for Scotland and 4 for Northern Ireland. The total numbers of clinics for each country were summed to give the number of clinics for the UK as a whole (i.e. 210).

For all scenarios both pathways were run in parallel over 1 year and their outcomes, in terms of number of recurrent strokes avoided and net budget impact, were compared.

Sensitivity analyses

A series of 1-way sensitivity analyses were performed on a base-case scenario of the UK population to evaluate the effect of varying certain key model assumptions (). To test the plausible range of the model results, the key assumptions in the model were adjusted to test a best-case and a worst-case scenario. The range of values analysed for TIA incidence was the lowest and highest rates as reported by Gibbs et al 2001Citation7. Referral rates from GP to outpatient clinic were varied between 50% (based on every other patient being referred) and the ideal scenario of all patients being referred. For outpatient clinics, it was assumed that the lowest number would be one per PCT (or local equivalent), and the highest if every general hospital in the UK (286 in total) provided a clinic. The range of values analysed for risk of recurrent stroke for the current care pathway was taken from an estimate of 10% higher or lower than the risk for the whole population reported by Coull et al 2004Citation1. The range of values for risk of recurrent stroke for the revised care pathway was varied between 1.24%, reported by Lavallée et al 2007 following the introduction of a 24-hour emergency clinic for the assessment and treatment of TIA in ParisCitation12, and 12.4% as reported in phase 1 of the EXPRESS study for the TIA populationCitation2. The range of values for the cost of acute stroke management was taken from an estimate of 10% higher or lower than the cost reported by Luengo-Fernandez et al 2006Citation7. In addition, the base-case assumption is that there will be no additional building and overhead costs associated with establishing a daily outpatient clinic. A scenario was therefore run where an additional 50% was included in staffing costs to account for any additional facility costs which may arise.

Results

The model predicted that for the five identified scenarios recurrent stroke events would be avoided with the implementation of the revised care pathway for patients experiencing TIA. Annually a total of 6,839 recurrent stroke events could be avoided in England, 401 in Wales, 690 in Scotland and 236 in Northern Ireland (). Across the UK as a whole, 8,164 recurrent stroke events could be avoided each year. In turn this could be associated with a predicted annual saving of nearly £60 million in management costs of acute stroke.

Table 2. TIA-related recurrent strokes avoided for patients presenting to GP.

The model predicts that, nationally, these savings may offset the costs of establishing the outpatient clinics (annual net savings for the UK = £25,646,695; ()). Net savings were also observed in England (£24,977,501), Scotland (£86,752) and Northern Ireland (£1,043,935). In Wales, annual costs of £446,827 were estimated ().

Table 3. Net budget impact in all scenarios.

Across the UK as a whole, the model suggests that the cost of the outpatient clinics in the revised care pathway could be £34,004,959 more than those in the current pathway. This is largely attributable to a 500% increase in staffing costs due to the assumption that a weekly outpatient clinic in the current care pathway would now be open Monday to Friday in the revised care pathway. By comparison, diagnostic and medication costs accounted for a small proportion of the rise in the revised care pathway costs. Diagnostic test costs were £9,705,965 in the current care pathway and £11,445,364 in the revised care pathway, whilst medication costs in the revised care pathway amounted to £1,672,122. The increase in outpatient clinic costs may be offset by the potential saving of £59,651,654 in acute management costs for recurrent stroke which would result in a total net saving over one year ().

The sensitivity analyses found that the annual number of strokes avoided was most sensitive to alteration of the risk of recurrent stroke in the revised care pathway (). For example, when the risk of recurrent stroke reported during phase 1 of the EXPRESS study was used in the revised care pathway (12.4%), 3,101 recurrent strokes were avoided. Alteration of the incidence of TIA and the GP to clinic referral rate also led to changes in the number of strokes avoided, with a 100% referral rate resulting in 11,832 recurrent strokes avoided.

Table 4. Results of one-way sensitivity analyses.

The sensitivity analysis showed the model to be robust and potential savings were observed in all analyses except where a high risk of recurrent stroke in the revised care pathway was used (12.4%), and in the worst-case scenario (where a low rate of referral from GP to clinic, a high number of clinics, low risk of recurrent stroke in the current care pathway, a high risk of recurrent stroke and additional facility costs in the revised care pathway were assumed).

Discussion

The model developed has demonstrated that reconfiguration of TIA care pathways across the UK to ensure rapid assessment and treatment could result in considerable cost savings and the potential avoidance of over 8,000 TIA-related strokes annually. The impact of such a change could be wide-ranging. As well as the short-term costs considered by the model, the healthcare system could see additional savings due to avoidance of long-term costs associated with ongoing care of stroke patients. Furthermore, the overall burden of disease could be reduced with fewer people suffering directly, or indirectly, from TIA-related stroke.

The scenarios considered assumed that one TIA outpatient clinic per PCT (or local equivalent) would be sufficient to provide for the local population. In England this would mean one clinic for approximately every 332,500 people – a population that would be estimated to have an annual TIA incidence of around 630, equivalent to the clinic assessing seven patients each week based on the referral rates assumed in the model. The authors consider this to be a manageable presentation rate that could enable effective management of patients within the clinic, especially if the clinic was available 5 days a week. While having a clinic open for 4 hours daily, seeing one or two patients, may seem a wasteful use of resources, it may be necessary in order to achieve the improved outcomes postulated as rapid access to assessment and treatment following a TIA is key to reducing the risk of recurrent stroke. The model suggests that the redistribution of current staff that would be required to provide the clinic could be associated with considerable benefit to patients.

It is important to note that the reconfiguration of TIA care pathways was not cost saving for all scenarios. However, despite the fact that savings were not seen in Wales, the reconfiguration of TIA care pathways could still be considered a valuable use of resources due to the 401 strokes that could be avoided each year. This is especially true if long-term costs are taken into account.

Considering the UK as a whole, the model demonstrates that the costs of running the outpatient clinics could greatly increase with the implementation of the revised care pathway. This is largely due to the 500% increase in staffing costs associated with running a daily clinic, suggesting that, in practice, a challenge in establishing the revised care pathway may be ensuring the availability of, and funding for, sufficient staff. In practice it may be that some clinical staff (e.g. consultant neurologist and radiographers) would not be present in the clinic at all times but would, instead, remain in their department but be ‘on call’ to the outpatient clinic. However, the model has taken a conservative approach that assumes staffing costs for all hours that the outpatient clinic is open would be attributed to the clinic itself.

It should also be recognised that staffing costs are largely independent of the number of patients attending the clinic and therefore increasing the referral rate to the clinic would not substantially increase the total costs of the clinic, but may increase the number of strokes avoided. In fact, as demonstrated by the sensitivity analyses, increasing the referral rate to the outpatient clinic to 100% would result in an increase in the number of strokes avoided to 11,832, which would increase the savings associated with the revised care pathway. Although a referral rate of 100% may be unrealistic, this indicates that any increase in the referral rate could ultimately have economic benefits.

The results of the model suggest that greater access to rapid assessment and treatment for those experiencing TIA, coupled with a greater awareness of the symptoms of TIA and the necessity for rapid treatment, could ultimately result in long-term savings to the healthcare system. The necessity for increasing healthcare professional awareness of TIA and its management has been recognised in other studies. For example in the SOS-TIA study by Lavallée et al 2007, an educational leaflet was sent to family doctors, neurologists and ophthalmologists in Paris in conjunction with the opening of a 24-hour emergency clinic for the assessment and treatment of TIACitation12.

The authors recognise that parameters within the model may need to be adjusted in order to assess accurately the local budget impact of reconfiguring the care pathway for patients experiencing TIA. One factor that would need to be established locally would be the number of clinics required to serve the population. To do this the geographical spread and demographics of the local population would need to be considered, particularly since TIA incidence across the UK has been reported to vary from 0.122% in North East Thames to 0.25% in YorkshireCitation7. In addition, local clinical practice would need to be reviewed in order to estimate the impact of reconfiguration.

The intention of the study was to estimate the potential impact of the reconfiguration of TIA care pathways in the UK, and the results rely on the key assumption that the clinical results reported in the EXPRESS study can be replicated in other clinics nationwide. The authors do not consider the revised care pathway modelled to be a definitive structure of care for patients with TIA; rather that it represents a framework of how care could be reconfigured and suggest the results of the model could act as an incentive for potential adoption of the revised care pathway. While further research is required to establish the benefits that would be achieved with stepwise improvements towards more rapid assessment and treatment of patients experiencing TIA, the authors suggest that incremental changes towards the care pathway outlined in phase 2 of the EXPRESS study could potentially have economic, as well as clinical, benefits.

Conclusion

TIAs may be warnings of future cerebrovascular events and could represent an opportunity to prevent recurrent stroke through rapid access to assessment and treatment. The model demonstrates that reconfiguration of TIA management in the UK to take advantage of this opportunity could reduce the incidence of future stroke events, and potentially result in cost savings to the healthcare system.

Acknowledgement

Declaration of interest: This work was supported by GE Healthcare.

A.J.B. and J.M. have disclosed that they are employees of Medaxial Limited, London UK; DJ has disclosed that he is an employee of GE Healthcare, Pollards Wood, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire UK.

References

- Coull AJ, Lovett JK, Rothwell PM, on behalf of the Oxford Vascular Study. Population based study of early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke: implications for public education and organisation of services. BMJ 2004;328:326–329.

- Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al; on behalf of the Early use of Existing Preventive Strategies for Stroke (EXPRESS) study. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet 2007;370:1432–1442.

- Luengo-Fernandez R, Gray AM, Rothwell PM. Effect of urgent treatment for transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on disability and hospital costs (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet 2009;8:235-243.

- Curtis L. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2008. Canterbury: Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) University of Kent, 2008.

- Department of Health. Implementing the National Stroke Strategy – an imaging guide. London, UK: Department of Health, May 2008.

- Department of Health. National Stroke Strategy. London, UK: Department of Health, December 2007.

- Gibbs RGJ, Newson R, Lawrenson R, . Diagnosis and initial management of stroke and transient ischemic attack across UK health regions from 1992 to 1996: experience of a national primary care database. Stroke 2001;32:1085-1090.

- Luengo-Fernandez R, Gray AM, Rothwell PM. Population-based study of determinants of initial secondary care costs of acute stroke in the United Kingdom. Stroke 2007;37:2579-2587.

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. [56] edn. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2008.

- Department of Health. NHS reference costs (Trust and PCT, 2006–2007). Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_082571 . Accessed February 2009.

- NHS pay – agenda for change – pay rates. Available at: http://www.nhscareers.nhs.uk/details/Default.aspx?Id=766 . Accessed February 2009.

- Lavallée PC, Mesequer E, Abboud H, . A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (SOS-TIA): feasibility and effects. Lancet 2007;6:953-960