Abstract

Objective: To describe the development and psychometric evaluation of a questionnaire assessing the ease of use that patients associate with patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) modalities.

Methods: Qualitative interviews were conducted with patients who had experience with intravenous (IV) PCA for postoperative pain management to generate items relevant to the ease of using PCA modalities. The content validity of the resulting questionnaire was examined through follow-up patient interviews, and an expert panel reviewed the questionnaire. Cognitive debriefing interviews were conducted with patients to determine the clarity and content of the instructions, items, and response scales, and the ease of completing the instrument. Psychometric evaluation was performed with patients who had undergone surgery and received IV PCA for postoperative pain management. Item and scale quality and the internal consistency reliability of the questionnaire were assessed. Construct validity was evaluated by examining the relationship between subscales of the questionnaire with patient-reported outcome measures. Known-groups validity was determined by assessing the instrument's ability to differentiate between patients with versus without an IV PCA problem. A potential limitation of this study was the exclusive sampling of patients who had experience with IV PCA.

Results: The Patient Ease-of-Care (EOC) Questionnaire included 23 items in the following subscales: Confidence with Device, Comfort with Device, Movement, Dosing Confidence, Pain Control, Knowledge/Understanding, and Satisfaction. Coefficient alpha reliability estimates were ≥0.66 for Overall EOC (includes all subscales except Satisfaction) and all EOC subscales. Construct validity was supported by the moderate relationship between the Pain Control subscale and measures of pain severity and pain interference; additional evidence of construct validity was provided by correlations of the Confidence with Device subscale, the Satisfaction subscale, and Overall EOC with measures of pain severity, pain interference, and satisfaction. Significant mean score differences were reported between participants with and without IV PCA problems for Overall EOC and for the Comfort with Device, Confidence with Device, Movement, Pain Control, and Satisfaction subscales indicating known-groups validity.

Conclusions: Results provide evidence for the reliability and validity of the Patient EOC Questionnaire as a measure of the ease of use that patients associate with PCA systems and may be useful for evaluating emerging PCA modalities.

Introduction

Effective postoperative pain management remains an issue of concern despite recent regulatory and clinical initiatives aimed at reducing the burden of pain among patients in the postoperative settingCitation1–6. Evidence suggests that 30% of patients still experience moderate-to-severe pain with intramuscular (IM) analgesia, intravenous (IV) patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), or epidural analgesia after major surgeryCitation7. Current endpoints of studies evaluating PCA methods of pain control generally focus on patient-reported measures of pain intensity and patient discontinuation ratesCitation8. However, investigations of PCA modalities suggest that knowledge and understanding of the PCA deviceCitation9–11, mobilityCitation12,13, satisfactionCitation14, and comfort with the PCA deviceCitation15 are equally important to consider.

Rosati and colleaguesCitation16 used a questionnaire to evaluate the ease of using an oral PCA device for the management of cancer pain in a pilot study (n=20). Although the questionnaire was reliable, no measures of validity were obtained, and a number of items were customized for the oral PCA system, limiting its usefulness with other PCA modalities. Another studyCitation17 used newly developed questionnaires that assess patients' satisfaction with pain relief, overall satisfaction with IV PCA, and anticipated satisfaction with transdermal analgesic delivery systems. These instruments were specifically designed to evaluate patient satisfaction with features of IV PCA or transdermal analgesic delivery systems, and therefore are also limited in their usefulness. As noted by Turk and colleaguesCitation18 and othersCitation19, there is a need to develop and test patient-reported outcome measures that may be used during the postoperative period to allow comparisons of various analgesic techniquesCitation19.

The purpose of this study was to validate a new instrument designed to reliably measure concepts related to ease of use associated with PCA.

Methods

Participants

All participants at all stages during the development and validation of the Patient Ease-of-Care (EOC) Questionnaire met the following inclusion criteria: had undergone or were scheduled to undergo orthopedic hip surgery or lower abdominal surgery, had received or were expected to receive IV PCA for postoperative pain management, were ≥18 years of age, were able to provide written informed consent to participate, and were able to speak and read English. For the qualitative interview and cognitive debriefing phases of the study, patients who had a cognitive or other impairment that would interfere with his/her ability to participate in a telephone interview (e.g. auditory or speech impairment) were excluded from study participation. For the qualitative patient interview, cognitive debriefing, and psychometric evaluation phases of the study, patients with a cognitive or other impairment that would prohibit him/her from independently reading and completing a paper-and-pencil survey (e.g. visual impairment) were excluded. All patients provided informed consent prior to study participation. In accordance with ethical practice, institutional review board approval at each institution was obtained for qualitative patient interviews, cognitive debriefing, and psychometric evaluation prior to the initiation of each phase of the study.

Questionnaire development

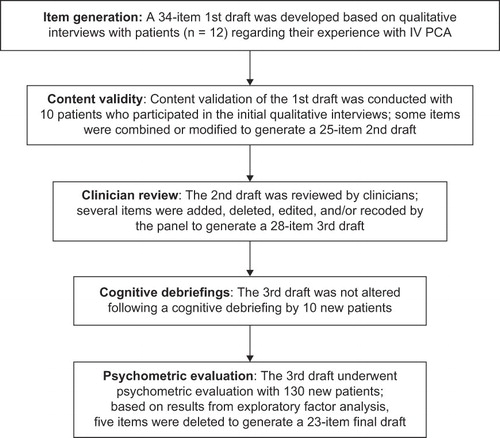

The steps involved in instrument development and testing of the Patient EOC Questionnaire, as outlined in , included qualitative interviews with patients, item generation, content validity examination, clinician review, and cognitive debriefing.

Figure 1. The development and psychometric evaluation of the Patient EOC Questionnaire followed standard questionnaire methodologies, as described by Juniper and colleaguesCitation28 and FDA patient-reported outcome draft guidanceCitation29.

The development of the instrument was based on underlying concepts (i.e. domains) that were identified and deemed important by patients with experience with IV PCA who participated in qualitative interviews. Patients who met the previously described inclusion and exclusion criteria were recruited to participate in qualitative telephone interviews regarding their experience with IV PCA, and to review and evaluate a draft questionnaire that would be developed based on these interviews. Interviews were scheduled within 7 days of discharge from the hospital and focused on patients' level of satisfaction with treatment and how easy or difficult it was for them to move around and perform certain tasks or activities. Participants were also asked demographic-related questions.

Item generation.

Items were generated through content analysis of the qualitative interviews. Two independent researchers reviewed the transcripts to identify important themes from cognitive debriefing interviews. General themes, issues, and concerns, along with direct quotes from patients, were used to generate items defining aspects of ease of PCA use and to design the initial draft of the Patient EOC Questionnaire. Items were selected based on relevance to the underlying construct, the importance to the patients, the clarity of the item and generalizability of items to patients' experiences with other PCA systems, and the contribution of the item to the overall flow of items, comprehensiveness, and clarity of the instrument. An initial draft of the Patient EOC Questionnaire was developed from this item pool.

Content validity.

To examine the content validity of the initial draft of the Patient EOC Questionnaire, patients who participated in the qualitative interviews were asked to participate in a follow-up, semi-structured telephone interview to review the draft questionnaire and rate the importance of each item. During the telephone interview, participants were asked to complete the questionnaire and rate the relevance (0 = ‘not at all relevant’ to 4 = ‘highly relevant’) and clarity of each item, as well as to comment on the response options.

Clinician review.

Based on this evaluation, the instrument was revised to form the second draft of the questionnaire and was distributed and reviewed by a group of clinicians, which included two pain medicine anesthesiologists, an orthopedic surgeon, a clinical pharmacist, a general surgeon, and two nurse researchers. The clinician review resulted in a third-draft, 28-item EOC questionnaire. This third draft was subjected to a cognitive debriefing with participation by ten new patients recruited according to the above inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Cognitive debriefing.

Cognitive debriefing interviews were conducted using the third draft of the instrument to evaluate patients' experiences, including their views on the ease with which the questionnaire could be completed, as well as the clarity and content of the instructions, items, and response scale.

Once the draft instrument was finalized, methods of scoring and rules for handling missing data were determined.

Psychometrics

The psychometric properties of the third draft of the Patient EOC Questionnaire were examined using data from a multi-site, cross-sectional study of patients who had undergone total hip replacement or lower abdominal surgery and received IV PCA for postoperative pain management. Study participants were recruited at three hospitals. Potential study participants were approached prior to their scheduled surgery to ascertain their interest in participating in the study and their eligibility for study enrollment based on the previously described inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients were asked to complete the Patient EOC Questionnaire along with four ancillary patient-reported outcome measures to examine the psychometric properties of the third draft of the Patient EOC Questionnaire. The four patient-reported outcome measures included the validated patient global assessment (PGA) of the method of pain controlCitation20, two scales (a pain severity and a pain interference scale) from the Brief Pain Inventory (BPICitation21), two patient satisfaction-related items (‘Select the phrase that indicates how satisfied or dissatisfied you are with the results of your pain treatment overall’ [6-point Likert-type scale ranging from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’] and ‘Select the phrase that indicates how satisfied or dissatisfied you are with the way your nurses responded to your reports of pain’ [6-point Likert-type scale ranging from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’) based on the work of Ware and colleaguesCitation22, and a pain management form that included a checklist of problems that patients may encounter with IV PCA. Details of these measures are provided in . Patients were given the booklet containing the patient-reported outcome measures at the time of IV PCA discontinuation or within 36 hours after discontinuation of IV PCA and prior to hospital discharge. Patients were assured of the confidential nature of their responses to instruments within the booklet. Patients also completed a brief questionnaire to provide details of their demographic and patient characteristics, including any prior experience with IV PCA. The time to ambulation following surgery was also recorded.

Table 1. Description of instruments used for construct validation of the Patient EOC Questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Psychometric analyses performed on the third draft of the Patient EOC Questionnaire were consistent with the traditional psychometric theoryCitation23. Descriptive statistics were used to present demographic characteristics. Psychometric evaluation was performed using PC SAS Version 8.02 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All statistical tests used a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05 unless otherwise noted.

Item reduction.

Distributional characteristics of individual items of the Patient EOC Questionnaire were examined, including the mean response, minimum and maximum responses (i.e. floor and ceiling effects, respectively), percent missing, and item-to-item correlations. The number of factors for the Patient EOC Questionnaire was determined using factor loadings and expert judgment and was set a priori to six (representing the six subscales used to calculate Overall EOC, which was calculated as the mean of items on those subscales and included all subscales except for Satisfaction), and eigenvalues and scree plots were used to determine the number of factors. Justification for item reduction included low item-to-Overall EOC correlations (< 0.40), inadequate factor loading (< 0.40) on any factor, or factor loading > 0.40 on more than one factor. The relative contribution of each item to the internal consistency reliability of multi-item subscales was also considered (items with Cronbach's alpha values < 0.70 were considered for deletion).

Reliability.

Reliability analyses were used to assess measurement error and the stability and consistency of the instrument. Cronbach's formula for coefficient alpha was used to estimate the internal consistency reliability of the EOC subscales and Overall EOC. Cronbach's alpha values > 0.70 were considered acceptableCitation23.

Construct validity.

To examine the construct validity of the Patient EOC Questionnaire, the pattern and magnitude of the relationship between the subscales and Overall EOC with the patient-reported outcome measures, including PGA of the method of pain control, pain severity, pain interference, satisfaction, and the number of self-reported problems due to IV PCA, and the time to ambulation were examined using Pearson product-moment correlations. Subscale-to-subscale correlations were also determined. The a priori range for r was 0.3–0.5.

To examine the known-groups validity of the Patient EOC Questionnaire, the effect of the presence or absence of IV PCA problems (as reported by patients on the pain management form) on Overall EOC and the EOC subscales was assessed using t-tests. Correlation effect sizes for differences in mean subscale and Overall EOC scores with the presence or absence of self-reported IV PCA problems were generated using Cohen's guide for social phenomenaCitation24 and the following formula: mean (absent) – mean (present)/SD (absent).

Results

Questionnaire development

A total of 15 patients were recruited to develop the initial Patient EOC Questionnaire draft, and 12 participated in qualitative interviews concerning their experience with IV PCA (; three could not be reached for participation). The mean age of the patients was 57.6 years, and the majority were female (75%) and white (83%). The majority (58%) of patients reported using IV PCA for 2 days, 25% reported using IV PCA for 3 days, and 17% reported using IV PCA for 4 days. Most patients (83%) indicated that they had used IV PCA for the first time during this hospital stay.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of patients participating in the development and psychometric evaluation of the Patient EOC Questionnaire.

Item generation.

The initial draft of the questionnaire included 34 items organized into seven areas associated with acute pain management systems: Mobility Limitations (6 items), Quality of Pain Control (4 items), Fears and Concerns (8 items), Control/Self-Efficacy (4 items), Problems with Device (5 items), Education (4 items), and Satisfaction (3 items). Items were formatted as statements and were scored on a 6-point Likert scale with the following response options: 0 = ‘not at all,’ 1 = ‘a little bit,’ 2 = ‘somewhat,’ 3 = ‘quite a bit,’ 4 = ‘a great deal,’ and 5 = ‘a very great deal.’

Content validity.

Ten of the original 15 recruited patients agreed to participate in a follow-up, semi-structured telephone interview to evaluate the content validity of the initial draft of the questionnaire; two of the 12 patients who participated in the initial qualitative interviews could not be reached. Mean ratings of relevance for each item ranged from 2.1 to 3.9. None of the items were rated as irrelevant (i.e. a score of 0 or 1) by more than 50% of the participants. Nearly all patients indicated that the items were clear and easy to understand and none of them reported difficulty with the response categories; however, patients did indicate that several of the items were redundant; hence, items were combined or modified as appropriate.

The content validation from the ten patients resulted in a revised second-draft, 25-item Patient EOC Questionnaire.

Clinician review.

Following review by clinicians, several modifications and minor wording edits were further made based on their feedback, including the addition of 3 reverse items (‘the device was difficult to use,’ ‘the beeps from the device made me worry that the device was not working properly,’ and ‘I used more pain medication than if a nurse or doctor had provided it regularly’), addition of an item to address annoyance with beeps from the device (‘the beeps from the device bothered/annoyed me’), and deletion of a satisfaction item (‘I like being responsible for giving myself pain medication’). Additionally, the response options for items on the Satisfaction subscale were modified so that responses ranged from 0 = ‘extremely dissatisfied’ to 5 = ‘extremely satisfied’; higher scores on the Satisfaction subscale indicated greater patient satisfaction with the pain management delivery system. The result was a third-draft, 28-item Patient EOC Questionnaire that consisted of seven subscales designed to evaluate PCA systems from the perspective of the patient.

Cognitive debriefing.

The third draft of the Patient EOC Questionnaire was subjected to a cognitive debriefing in ten new patients recruited approximately 36–48 hours following surgery, while the patients were using IV PCA, or prior to hospital discharge, and their demographic information was collected. The demographic characteristics of nine of the ten patients participating in the cognitive debriefing are given in . The mean age of these patients was 60 years; the majority of the patients were female (67%) and white (67%). All of the patients indicated that they had previously undergone hip replacement, and 56% reported that they had prior experience with IV PCA. Overall, patients reported that the instrument and response options were clear and easy to understand. Based on these findings, no changes were made to the third-draft, 28-item EOC questionnaire prior to psychometric evaluation and validation.

Psychometrics

A total of 130 patients participated in the psychometric evaluation of the Patient EOC Questionnaire (). Patients were primarily female (71.5%) and white (74.6%), and had a mean age of 49.0 years. The majority of patients (86.9%) were ambulatory 1 day after surgery. Patients reported pain (17.7%), itching (16.9%), and swelling/bruising (14.6%) where the IV catheter was inserted, difficulty locating the dosing button (9.2%), pump malfunction (6.2%), and infiltration (4.6%). Less than half (40%) of patients reported that they had prior experience with IV PCA.

In general, patients used the full range of responses for items on the Patient EOC Questionnaire. Mean (standard deviation [SD]) scores for the items ranged from 2.63 (1.40) to 4.82 (0.74); the mean (SD) scores for items that were retained in the questionnaire following item reduction are given in . While floor effects were minimal (0.8–20.9%), ceiling effects were particularly high for several items, which all had a maximum response option of ‘not at all,’ indicating that the majority of patients did not experience the worries or difficulties described in these items. Items with high ceiling effects included the following: ‘The device was difficult to use,’ 92.3%; ‘I had soreness/irritation on my skin where the device was attached,’ 86.6%; ‘I was worried that a nurse or doctor was not monitoring how much pain medication I was taking,’ 84.6%; ‘The beeps from the device made me worry that the device was not working properly,’ 83.7%; and ‘My pain control was interrupted because of problems with the device,’ 83.1%.

Table 3. Mean (SD) scores, final factor loadings, and internal consistency reliability for items and/or subscales of the Patient EOC Questionnaire after item reduction*.

The number of missing responses for individual items was < 5% for all items. With respect to item-to-item correlations, no single item was highly correlated with another item measuring the same concept (r< 0.80 for all correlations).

Final Patient EOC Questionnaire.

Based on the psychometric evaluation results, 5 items were deleted from the third draft of the questionnaire: exploratory factor analysis of subscales that contributed to Overall EOC indicated that three items (‘My pain level was controlled,’ ‘The beeps from the device reassured me that it was working properly,’ and ‘I used more pain medication than if a nurse or doctor had provided it regularly’) did not have adequate factor loading on any factor (factor loadings ≤0.40 for all) and were deleted; one item (‘The device was difficult to use’) was deleted due to high ceiling effects (92.3% of patients reported ‘not at all’); one item (‘I used less pain medication than if a nurse or doctor had provided it regularly’) was deleted because it limited the Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the Quality of Pain Control subscale (i.e. the Quality of Pain Control subscale Cronbach's alpha coefficient increased from 0.53 to 0.66 when this item was deleted). Although 5 items had high ceiling effects, only 1 of the items was deleted because it also demonstrated highly skewed distribution. The other items were retained based on their performance in terms of response distribution and the potential to detect differences with respect to ease of care in a larger sample size. In addition, results showed that a number of items loaded more heavily on a subscale other than the one initially proposed.

The final factor loadings appear in . Factor loadings were ≥0.48 for all items, with the exception of ‘I had soreness/irritation on my skin where the device was attached’ (factor loading = 0.327). This item can potentially differentiate ease of use between PCA systems.

The final Patient EOC Questionnaire consists of 21 items (not including the two satisfaction items) sorted into six subscales, which were named to better reflect the item groupings and the conceptual domains represented by the measure: Confidence with Device, Knowledge/Understanding, Comfort with Device, Movement, Dosing Confidence, and Pain Control. Subscales are each scored separately as the mean of items comprising that scale. Higher scores represent better ease of care for patients using the delivery system. An Overall EOC score is calculated as the mean of the subscale scores for Confidence with Device, Comfort with Device, Movement, Dosing Confidence, Pain Control, and Knowledge/Understanding. Satisfaction is designed to capture the patient's satisfaction with the process and outcome of care (i.e. EOC and pain control). As such, it is not included in the Overall EOC score. Higher scores on the satisfaction subscale indicate greater patient satisfaction with the pain management delivery system. A 60% rule is used to handle missing data. That is, if more than 40% of responses are missing for any given subscale, a subscale score is not calculated (i.e. the subscale is considered missing). The total scale score is computed by taking the mean across all subscale scores; all subscale scores must be present to compute a total scale score. This scoring algorithm is such that each subscale or construct is equally represented in the total score.

Instrument performance.

Distribution characteristics of subscales after item reduction identified by exploratory factor analysis indicated that mean (SD) subscale scores ranged from 3.34 (1.29) for Pain Control to 4.63 (0.67) for Confidence with Device (). In terms of ceiling and floor effects, less than 55% reported a maximum response on any subscale, and less than 2% reported a minimum response. Overall EOC and Satisfaction were significantly correlated (r=0.51; p< 0.001), and all correlations between the subscales and Overall EOC were significant, ranging from r=0.29 to 0.64 (p< 0.05 for all) (). The internal consistency reliability was adequate, as all subscales and Overall EOC had a Cronbach's alpha value ≥0.70, with the exception of the Pain Control subscale (Cronbach's alpha = 0.66) ().

Table 4. Pearson product-moment correlations between subscales and Overall EOC with patient-reported outcome measures and subscale-to-subscale correlations.

Correlations between the subscales and the patient-reported outcome measures indicated that the subscales on the Patient EOC Questionnaire were correlated with clinically relevant measures (). Correlations between the Pain Control subscale and BPI items (r=–0.43 to –0.28; p< 0.01 for all) indicated a moderate relationship between this subscale and the two ancillary measures of pain severity and pain interference. In addition, Overall EOC scores were significantly correlated with all BPI pain severity and pain interference items (r=–0.29 to –0.19; p< 0.05 for all), except BPI pain interference with sleep (r=–0.11). The Confidence with Device, Movement, Pain Control, and Satisfaction subscales and Overall EOC were significantly correlated with responses to satisfaction with pain treatment overall (p< 0.05 for all).

With respect to known-groups validity (), there was a significant difference in mean subscale scores between those who reported the presence versus the absence of IV PCA problems for the Comfort with Device, Confidence with Device, Movement, Pain Control, and Satisfaction subscales and for Overall EOC (p< 0.05 for all) with effect sizes ranging from 0.59 to 1.29, indicating that the subscales and Overall EOC were able to distinguish between individuals who differed on a key clinical indicator.

Table 5. Known-groups validity: analysis of the Patient Overall EOC and subscale scores compared with the presence/absence of self-reported IV PCA problems.

Discussion

The Patient EOC Questionnaire captures the multidimensional components of patient experiences and perceptions associated with the use of a PCA modality for self-management of pain. Instrument construction was based on respondent qualitative data elicited from patients who received PCA for postoperative pain management and, as such, included concepts relevant to their experiences and deemed important. Empirical examination of the Patient EOC Questionnaire demonstrated evidence of internal consistency reliability and validity. All reliability estimates (Cronbach's alpha values) were ≥0.70 for all subscales, with the exception of Pain Control (Cronbach's alpha = 0.66). This lower estimate may be because the scale included only 2 items, since generally as the number of items on a scale increases, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient increases as well. Correlations between all EOC subscales and Overall EOC were significant (p< 0.05 for all), confirming that all of the subscales contributed to the Overall EOC score without presenting redundancy. Although the Confidence with Device subscale was slightly more strongly correlated to Overall EOC compared with the other subscales, results indicated that concepts measured by the subscales contributed to Overall EOC and that no single subscale drove the Overall EOC score. In addition, the correlation between Overall EOC and Satisfaction (0.51; p< 0.001) suggested that ease of use is associated with patient satisfaction.

With respect to construct validity, all of the initial a priori expectations regarding relationships between Overall EOC and ancillary measures could not be tested because the final subscales were modified based on psychometric evaluation. However, several important patterns and relationships consistent with a priori expectations were demonstrated. In particular, the Pain Control subscale was significantly correlated with BPI measures of pain severity and pain interference (ranging from r=–0.43 to –0.29; p< 0.01 for all) and PGA of the method of pain control (r=0.34; p< 0.001). While the BPI scales were originally developed to assess pain associated with chronic diseases (particularly cancer pain), they have also been used to assess acute postoperative pain, including pain following coronary artery bypass graft surgeryCitation25,26 and pain following different surgery incision typesCitation27. Our findings are consistent with expectations that the quality of pain control would be at least moderately correlated with average pain severity and PGA of the method of pain control. The correlation between Overall EOC and the Satisfaction subscale items concerning patients' ratings of their pain treatment overall was also moderate (r=0.20; p< 0.05). While this correlation may seem modest, it should be noted that the correlation between Overall EOC and PGA of the method of pain control was much stronger (r=0.47; p< 0.001), suggesting that an evaluation of the method of pain control may be associated with patients' perceived ease of use. Overall EOC also correlated significantly with other validated measures of BPI pain severity and pain interference. As expected, strong inter-correlations were not found between all of the subscales, indicating that some of the subscales for the Patient EOC Questionnaire are independent of one another and measure discrete conceptual domains of PCA use and experiences. Further, EOC subscales did not correlate strongly with specific measures of the BPI, the PGA of the method of pain control, and the satisfaction items. Various subscales for the EOC instrument are not measuring the same concepts; however, moderate to low correlations were found between the EOC subscales and items and subscales from other pain measures, which show some degree of covariation. Together, these data indicate that the Patient EOC Questionnaire may be able to assess items relevant to patients' postoperative pain management experiences (e.g. pain control, patient mobility, and overall ease of care) and is correlated with clinical measures (e.g. PGA of the method of pain control, pain severity, and satisfaction with pain control). Further analysis is warranted to determine the clinical significance of these statistically significant correlations.

The Patient EOC Questionnaire also demonstrated known-groups validity with regard to the presence or absence of IV PCA self-reported problems (p< 0.05 for all) for Overall EOC and all EOC subscales (with the exception of the Knowledge/Understanding and Dosing Confidence subscales), suggesting that the instrument may be able to distinguish responses on this important clinical indicator. Because the Patient EOC Questionnaire was developed through patient-generated data from experiences of those who used IV PCA for the management of acute postoperative pain, it was possible to capture the critical indicators of greatest importance to those users.

As previously stated, Rosati and colleaguesCitation16 used a questionnaire to evaluate the ease of using an oral PCA device for the management of cancer pain, and although evidence of reliability was presented, the validity of the questionnaire was not assessed. A separate study by Gan and colleaguesCitation17 used two questionnaires to evaluate patients' satisfaction with pain relief, their overall satisfaction with IV PCA, and their expected satisfaction with transdermal analgesic delivery systems; however, the psychometric properties of the questionnaires were not evaluated. Rothman and colleaguesCitation20 showed that the patient global assessment of the method of pain control was significantly associated with patient-reported outcomes of pain intensity and satisfaction ratings and provided evidence of its validity; however, that measure is not intended to assess the ease of using postoperative methods of pain control. To the best of our knowledge, evidence for the development and validation of a questionnaire similar to the Patient EOC Questionnaire has not been presented.

A potential limitation of this study was the exclusive sampling of patients who were administered IV PCA. Ideally, more PCA modalities (e.g. epidural PCA) would have been included in the development of this questionnaire, which is designed to assess the EOC associated with any postoperative PCA system. However, we believe the core elements of the Patient EOC Questionnaire are useful for evaluating the EOC of any PCA modality. In addition, all patients completed the Patient EOC Questionnaire and ancillary measures within a specified window (i.e. at the time of IV PCA discontinuation or within 36 hours after discontinuation of IV PCA, prior to hospital discharge). While it would have been ideal for all patients to complete the questionnaire at the time of IV PCA discontinuation, the time frame within which all questionnaires were completed was relatively short, thereby minimizing problems related to patient recall. All patients who participated in the study underwent either orthopedic or abdominal surgery, and may not be representative of all postoperative patients who receive PCA treatment. However, the development and testing strategy of this study followed standard questionnaire methodologiesCitation28, followed the FDA guidance for the development of patient-reported outcome measuresCitation29, and involved careful statistical analyses for determining construct and known-groups validity. Although the instrument was constructed to evaluate PCA systems, the development and psychometric evaluation processes included only patients who received IV PCA. Additional studies are necessary to determine the reliability and validity of the Patient EOC Questionnaire in patients undergoing various surgical procedures and in patients using emerging PCA delivery systemsCitation30.

Given the current state of postoperative pain care and the scarcity of patient-reported outcome measures that evaluate patients' ease of use with analgesic modalities, there is a need for comprehensive tools, such as the Patient EOC Questionnaire, for evaluating current and emerging PCA systems. The Patient EOC Questionnaire offers a way to measure multiple dimensions of patients' perceptions and experiences with PCA that may not be captured by other instruments. The questionnaire can be used in analgesic clinical trials and other studies of postoperative pain control to evaluate the benefits of PCA in the armamentarium of treatment modalities for pain management. Additionally, this instrument has potential for use with performance improvement activities in both evaluations of the relative contributions of emerging technologies to patient care and in value analysis and resource management initiatives.

Conclusion

With emerging PCA technologies and delivery systems being introduced into hospital settings, instruments to measure ease of use would be particularly useful for conducting product evaluations, measuring patient acceptance and satisfaction with care, and rating the ease with which devices and drug delivery systems can be used. Future PCA research must be expanded to measurement outcomes beyond pain control to include a patient-centered focus on all aspects of pain management that are of concern to patients, such as confidence with PCA modalities, knowledge and understanding of PCA modalities, comfort with PCA modalities, and movement. The current study provides strong evidence for the reliability and validity of the Patient EOC Questionnaire. Additional studies are necessary to determine whether the questionnaire is also a valuable tool for comparing and contrasting experiences with other PCA modalities.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Interest: This study was supported by Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. G.H. has disclosed that she is an employee of United BioSource Corporation; J.R.S. has disclosed that he is an employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; W.W.N. has disclosed that she is an employee of Johnson & Johnson; S.V. has disclosed that she is an employee of Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Services, LLC; W.H.O. has disclosed that he is an employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; D.J.H. has disclosed that he was an employee of Johnson & Johnson at the time this research was conducted; R.P. has disclosed that she is on the Speakers' Bureau for Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, and King Pharmaceuticals.

A portion of the results included in this manuscript was presented at the 25th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Pain Society, May 3–6, 2006.

The authors would like to thank Nancy K. Leidy, PhD, United BioSource Corporation; Eugene Viscusi, MD, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA; and Ming Zhang, PhD, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC for their assistance in the design of the Patient EOC Questionnaire, and Carmela Benson, MS, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC for reviewing this paper. Editorial assistance was provided by Ashley O'Dunne, PhD, of MedErgy and funded by Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

References

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Practical guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting. Park Ridge, IL, 2003

- American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain. Glenview, IL, 2003

- American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Pain Management, Acute Pain Section. Anesthesiology 1995;82:1071-1081

- Gordon DB, Dahl JL, Miaskowski C, American Pain Society recommendations for improving the quality of acute and cancer pain management: American Pain Society Quality of Care Task Force. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1574-1580

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Pain Assessment and Management: An Organizational Approach. Oakbrook, IL: JCAHO, 2000

- Rathmell JP, Wu CL, Sinatra RS, Acute post-surgical pain management: a critical appraisal of current practice. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2006;31:1-42

- Dolin SJ, Cashman JN, Bland JM. Effectiveness of acute postoperative pain management: I. Evidence from published data. Br J Anaesth 2002;89:409-423

- Lehmann KA. Recent developments in patient-controlled analgesia. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;29:S72-89

- Chen PP, Chui PT, Ma M, Gin T. A prospective survey of patients after cessation of patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg 2001;92:224-7

- Chen HH, Yeh ML, Yang HJ. Testing the impact of a multimedia video CD of patient-controlled analgesia on pain knowledge and pain relief in patients receiving surgery. Int J Med Inform 2005;74:437-445

- Chumbley GM, Ward L, Hall GM, Salmon P. Pre-operative information and patient-controlled analgesia: much ado about nothing. Anaesthesia 2004;59:354-358

- Wu CL, Cohen SR, Richman JM, Efficacy of postoperative patient-controlled and continuous infusion epidural analgesia versus intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with opioids: a meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2005;103:1079-1088

- Wu CL, Rowlingson AJ, Partin AW, Correlation of postoperative pain to quality of recovery in the immediate postoperative period. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005;30:516-522

- Bainbridge D, Martin JE, Cheng DC. Patient-controlled versus nurse-controlled analgesia after cardiac surgery – a meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth 2006;53:492-499

- Sawaki Y, Parker RK, White PF. Patient and nurse evaluation of patient-controlled analgesia delivery systems for postoperative pain management. J Pain Symptom Manage 1992;7:443-453

- Rosati J, Gallagher M, Shook B, Evaluation of an oral patient-controlled analgesia device for pain management in oncology inpatients. J Support Oncol 2007;5:443-448

- Gan TJ, Gordon DB, Bolge SC, Allen JG. Patient-controlled analgesia: patient and nurse satisfaction with intravenous delivery systems and expected satisfaction with transdermal delivery systems. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:2507-2516

- Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Burke LB, Developing patient-reported outcome measures for pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2006;125:208-215

- Liu SS, Wu CL. The effect of analgesic technique on postoperative patient-reported outcomes including analgesia: a systematic review. Anesth Analg 2007;105:789-808

- Rothman M, Vallow S, Damaraju CV, Hewitt DJ. Using the patient global assessment of the method of pain control to assess new analgesic modalities in clinical trials. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:1433-1443

- Daut RL, Cleeland CS, Flanery RC. Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain 1983;17:197-210

- Ware JE Jr., Snyder MK, Wright WR, Defining and measuring patient satisfaction with medical care. Eval Program Plann 1983;6:247-263

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988

- Mendoza TR, Chen C, Brugger A, The utility and validity of the modified brief pain inventory in a multiple-dose postoperative analgesic trial. Clin J Pain 2004;20:357-362

- Mendoza TR, Chen C, Brugger A, Lessons learned from a multiple-dose post-operative analgesic trial. Pain 2004;109:103-109

- Ochroch EA, Gottschalk A, Augoustides JG, Pain and physical function are similar following axillary, muscle-sparing vs posterolateral thoracotomy. Chest 2005;128:2664-2670

- Juniper E, Guyatt G, Jaeschke R. How to develop and validate a new health-related quality of life instrument. In: Spilker B, ed. Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven, 1996

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Guidance for Industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Silver Springs, MD: FDA, 2006

- Heitz JW, Witkowski TA, Viscusi ER. New and emerging analgesics and analgesic technologies for acute pain management. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009;22:608-617