Abstract

Objective: To estimate the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for abatacept and rituximab, in combination with methotrexate, relative to methotrexate alone in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods: A patient-level simulation model was used to depict the progression of functional disability over the lifetimes of women aged 55–64 years with active RA and inadequate response to a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antagonist therapy. Future health-state utilities and medical care costs were based on projected values of the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI). Patients were assumed to receive abatacept or rituximab in combination with methotrexate until death or therapy discontinuation due to lack of efficacy or adverse events. HAQ-DI improvement at month 6, after adjustments for control drug (methotrexate) response, was derived from two clinical trials. Costs of medical care and biologic drugs, discounted at 3% annually, were from the perspective of a US third-party payer and expressed in 2007 US dollars.

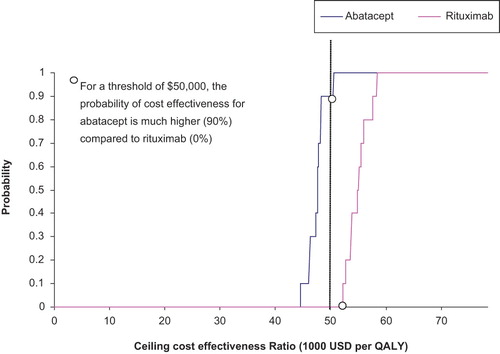

Results: Relative to methotrexate alone, abatacept/methotrexate and rituximab/methotrexate therapies were estimated to yield an average of 1.25 and 1.10 additional QALYs per patient, at mean incremental costs of $58,989 and $60,380, respectively. The incremental cost-utility ratio relative to methotrexate was $47,191 (95% CI $44,810–49,920) per QALY gained for abatacept/methotrexate and $54,891 (95% CI $52,274–58,073) per QALY gained for rituximab/methotrexate. At an acceptability threshold of $50,000 per QALY, the probability of cost effectiveness was 90% for abatacept and 0.0% for rituximab.

Conclusion: Abatacept was estimated to be more cost effective than rituximab for use in RA from a US third-party payer perspective. However, head-to-head clinical trials and long-term observational data are needed to confirm these findings.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic and progressive inflammatory disease of the joints that directly affects patients' physical functioning. Currently, the estimated prevalence of RA in the US is between 0.5 and 1.0%, whereas about 50% of patients have ‘disabled RA’ defined as Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) score > 1.0Citation1. The progression of RA can be slowed by treatment with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). DMARDs include the conventional, small-molecule drugs, the most commonly used of which is methotrexate (MTX), and biologic drugs of various classes. The tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antagonists, infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab, are biologic drugs targeted against pro-inflammatory cytokines. Anakinra, another biologic, targets interleukin-1, which is a cytokine with both immune and pro-inflammatory actions.

Two newer biologics, abatacept and rituximab, act via T cells and B cells, respectively. Abatacept is a selective co-stimulation modulator that inhibits T cell (T lymphocyte) activation. Clinical trials have shown that both abatacept and rituximab are effective in patients with active, moderate-to-severe RA despite treatment with MTXCitation2–6. In addition, trials have demonstrated that abatacept and rituximab, in combination with MTX, provide significant and clinically meaningful improvements in physical functioning in patients with moderately-to-severely active RA and an inadequate response to anti-TNFα therapiesCitation7,8.

Abatacept and rituximab are approved in the US for use in patients with moderately-to-severely active RA and an inadequate response either to MTX (abatacept) or to one or more TNFα antagonists (rituximab)Citation9,10. The acquisition costs of these and other biologic drugs are, however, substantially greater than those of traditional DMARDs. Cost-utility analysis is an accepted means of comparing alternative treatments by addressing both treatment costs and effectiveness, expressed in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gainedCitation11. Furthermore, a formal cost-effectiveness analysis is becoming increasingly important in the US to enable third parties to make informed formulary or reimbursement decisionsCitation12.

The primary objective of this analysis is to estimate the lifetime cost-utility of abatacept and rituximab from a US third-party payer perspective in patients with active RA and who have had an inadequate response to anti-TNFα therapy.

Materials and methods

Model description

A previously developed probabilistic patient-level simulation model was applied in this study to compute the progression of functional disability over timeCitation13. A similar modeling approach has been employed in other cost-utility evaluationsCitation14–16. The model simulates the progression of functional disability over the lifetimes of a hypothetical cohort of 10,000 women 55–64 years of age with moderately-to-severely active RA and an inadequate response to TNFα antagonists. Women 55–64 years are prominently represented among patients with RACitation17 and this age and gender category has been the base-case population in other similar CU modeling studiesCitation13,18. Functional disability is expressed in terms of the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) scoreCitation19, which ranges from 0, representing no limitation in activities of daily living, to 3, representing complete inability to perform these activities. The model simulates progression of HAQ-DI score over intervals of 3 months (the model cycle time), when treatment decisions are made (continuation or discontinuation of current therapy) and health-state utilities and costs are computed. Health-state utilities, mortality, and medical-care costs (other than for study drug treatment) are assumed to depend on HAQ-DI scores. A 3-month cycle was chosen primarily based on a need for a data update or decision point flexible within a shortest time interval. Patients are assumed to receive either abatacept or rituximab in combination with MTX, or MTX monotherapy, on a lifelong basis or until therapy discontinuation due to lack of efficacy or side-effects. The model permits discontinuation of treatment due to failure to attain clinically meaningful improvement (user-specified) in RA symptoms to occur at 3 or 6 months following therapy initiation.

Parameter estimates

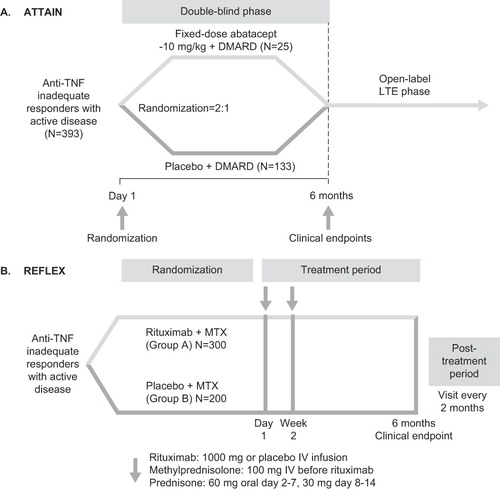

The data sources for on-biologic HAQ-DI scores were the 6-month ATTAIN (Abatacept Trial in Treatment of Anti-TNF Inadequate Responders)Citation7 and REFLEX (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Efficacy of Rituximab in RA)Citation8 trials. The designs of these trials are shown in .

At model entry, each patient in the cohort was randomly assigned an initial value for HAQ-DI score by sampling (with replacement) from the actual distribution of HAQ-DI values at baseline in the ATTAIN trial. Since the characteristics of patients entering the ATTAIN and REFLEX trials were similar (, p< 0.05 for all), it was assumed that the HAQ-DI distribution in REFLEX was the same as in ATTAIN. The baseline distribution of HAQ-DI scores and other parameter estimates are presented in .

Table 1. Characteristics of patients at baseline in the ATTAIN and REFLEX trials*.

Table 2. Estimates of clinical parameters used in the cost-utility model.

Disease progression with MTX monotherapy was assumed to be represented by an annual increase in HAQ-DI of 0.065, a value derived from the Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Study (ERAS)Citation13,14. The initial response to abatacept/MTX or rituximab/MTX treatment (i.e., the proportional change from baseline in HAQ-DI score at 6 months) was derived from the ATTAIN and REFLEX trials. To account for the differences between trials in the control (MTX) treatment response, a method proposed by Choi et al and applied by other authorsCitation15 was used to adjust response rates of the biologic treatment group in different trials to the same scaleCitation20,21. This:

where

and where ‘response’ is the proportional change from baseline in HAQ-DI at 6 months; EBiol B is the ‘net efficacy’ (net drug effect of biologic drug B in trial B after adjusting for the MTX effect in trial B), representing the normalized probability of achieving a response with each drug after subtracting the effect of MTX; and RBiol B, RMTX A, RMTX B represent, respectively the unadjusted response rates of biologic B, MTX in trial A, and MTX in trial B. After adjustments for MTX response, the relative mean (SD) HAQ-DI improvements at month 6 were –25% (0.337) and –22% (0.316), respectively in the abatacept and rituximab trials (). For patients remaining on active therapy beyond 6 months, the percentage improvement in the HAQ-DI seen at 6 months was assumed to persist over time.

Patients were assumed to discontinue abatacept or rituximab if treatment failed to achieve a > 0.5 point reduction in HAQ-DI at month 6. Rates of discontinuation for reasons other than lack of efficacy (e.g., adverse events, patient choice) were assumed to be the same based on the observations from the ATTAIN trialCitation16. For those discontinuing therapy, HAQ-DI was assumed to return to a value equal to that with MTX only.

Mortality was assumed to be a function of gender, age, and HAQ-DI valueCitation13. Similarly, health-state utility values were assumed to depend on HAQ-DI score, based on the relationship between HAQ-DI and the EQ-5D Weighted Health Index for patients with RACitation13,22.

Costs were from the perspective of US third-party payers and were expressed in 2007 USD. Costs of study drug acquisition, administration, and monitoring, and costs of medical care (determined by HAQ-DI score) were based on product labelingCitation9, wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) prices and the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS)Citation13. Abatacept treatment cost was estimated at $20,614 (drug acquisition $18,100, administration cost $2,324, monitoring $190) in the first year, and $19,146 (drug acquisition $16,807, administration cost $2,158; monitoring $181) in each of the subsequent years. Patients weighing < 60 kg were assumed to receive two vials (500 mg) per infusion; 60–100 kg, three vials (750 mg); and > 100 kg, four vials (1 g). The distribution of RA patients by body weight (< 60 kg, 23.5%; 60–100 kg, 65.7%; > 100 kg, 10.8%) was estimated using data from the US Third National Health and Nutrition examination Survey (NHANES III)Citation13. The cost of abatacept was assumed to be $450/250 mg vial, with 14 IV infusions in the first year on therapy and 13 per year thereafterCitation13. The cost of each 30-minute infusion was assumed to be $166 based on the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS)Citation13. The costs for routine monitoring for patients receiving abatacept or rituximab were assumed to $190 (including baseline) in the first year, and $181 in each of the subsequent yearsCitation13

Rituximab treatment cost was estimated at $21,264 (drug acquisition $19,964, administration cost, $1,110, monitoring $190) in the first year, and $21,255 (drug acquisition $19,964, administration cost $1,110, monitoring $181) in each of the subsequent years, assuming two courses of rituximab per yearCitation10,23. The cost of the first hour infusion was assumed to be $166, and $37 for the next half-hour based on the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS)Citation13. The annual cost of treatment with MTX was assumed to be $600, based on assumed dose of 15 mg weeklyCitation13. Costs and outcomes were discounted at 3% annuallyCitation24.

Analyses

The model was developed using MS Excel spreadsheets with Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) codes to run all calculations and simulations. Monte Carlo simulationCitation25–27 was employed to estimate trends in HAQ-DI values over patients' lifetimes. First-order (or ‘random walk’) simulations were performed by running each patient in the hypothetical cohort through the model one at a time. Outcomes for the cohort as a whole were obtained by summing the measures of interest across all patients. Means and 95% CI values for QALYs and costs were generated. Cost utility was expressed in terms of the incremental cost per QALY gained with abatacept or rituximab in comparison with MTX alone.

Second-order simulations (to account for parameter uncertainty) were performed by running the model for 100 samples of 1000 patients each. Three key model parameters – the percentage change in the HAQ-DI at 6 months with biologic therapy, the health-state utility value by HAQ-DI interval, and the total cost of all other direct medical care services by HAQ-DI interval – were allowed to vary stochastically in these simulations, based on assumed normal probability distributions. The distribution of health-state utilities within each HAQ category was assumed to be normal, based on visual inspection of the plotted data. The probability that abatacept or rituximab would be cost effective at various willingness-to-pay thresholds was displayed in cost-utility acceptability curves. A cost-utility threshold of $50,000 is generally accepted for the USCitation28.

Deterministic sensitivity analyses were undertaken by varying selected assumptions and parameter estimates for abatacept and rituximab for which probability distributions were not available. These included: no discontinuation of biologic therapy for lack of efficacy or other reasons; the odds ratio (OR) for mortality associated with each 1-point increase in HAQ-DI score; the expected rate of disease progression (i.e., annual increase in HAQ-DI); and the threshold for a clinically meaningful improvement in HAQ-DI score (i.e., –0.25 and –0.75 vs. –0.50). Demographic categories other than women 55–64 years of age were also examined.

Results

Relative to MTX monotherapy, abatacept/MTX was estimated to yield an average of 1.25 additional lifetime QALYs per patient, at a mean incremental cost of $58,989 (). Rituximab/MTX was estimated to yield an average of 1.10 additional QALYs per patient relative to MTX, at a mean incremental cost of $60,380. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio relative to MTX monotherapy was $47,191 (95% CI $44,810–49,920) per QALY gained for abatacept/MTX and $54,891 (95% CI $52,274–58,073) per QALY gained for rituximab/MTX.

Table 3. Outcomes and costs per patient with abatacept and rituximab versus methotrexate.

Cost-utility acceptability curves are presented in . At a threshold of $70,000 per QALY, the probability that both biologics would be cost effective was unity. Conversely, at a threshold of $30,000 per QALY, neither abatacept nor rituximab would be likely to be cost effective. However, at a threshold of $50,000 per QALY, the probability of cost effectiveness was 0.90 for abatacept and 0.0 for rituximab.

In the deterministic sensitivity analyses, shown in , only ‘no therapy discontinuation’ (Scenario 1) and age > 85 years (Scenarios 14 and 21) changed (increased) the cost-utility ratio by more than 10% in both biologics; a threshold for a clinically meaningful improvement in HAQ-DI of –0.25 (Scenario 6) increased the cost-utility ratio by more than 10% for rituximab but not abatacept. With minor exceptions (women ≥75 years and men 18–34 years), none of the 95% CI intervals of the cost-utility ratios of abatacept and rituximab overlapped.

Table 4. Sensitivity analyses on key model assumptions and parameter estimates.

Discussion

In this analysis, lifetime treatment with abatacept was estimated to have lower treatment costs and greater improvement in HAQ-DI score, when compared with rituximab. The lifetime CU ratios of $47,191 per QALY gained for abatacept/MTX and $54,891 per QALY gained for rituximab/MTX versus MTX are generally in the same range as CU ratios in other modeling studies. An incremental cost of $43,041 per QALY gained for abatacept/MTX versus MTX was reported by Vera-Llonch et al for lifetime treatment of women 55–64 years of age with moderately-to-severely active RA and an inadequate response to MTXCitation13; the corresponding value for women with an inadequate response to anti-TNFα drugs was $45,979Citation16. Spalding and Hay reported CU ratios for TNFα inhibitors as first-line agents (again for US women, 55–60 years of age)Citation18. Incremental CU ratios were $63,769, $89,772, and $409,523 per QALY gained for adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab/MTX, respectively, versus MTX monotherapy. Wong et al reported a lifetime CU ratio of $30,500 per QALY gained for infliximab/MTX versus MTX monotherapyCitation29. All of these CU estimates considered direct medical costs, and excluded indirect costs.

Numerous cost-effectiveness or cost-utility analyses of the biologic anakinraCitation30 and the anti-TNFα drugsCitation14,15,18,20,29,31–36 have been reported. Some of these were true cost-effectiveness analyses – Choi et al expressed costs as treatment costs and effects in terms of ACR responseCitation20,21 – but most were cost-utility analyses, in which the ‘effects’ were expressed in terms of QALYs. In some analyses, Markov, i.e. transition state, models were developed, in which patients were assumed to periodically transition from one categorical disability state to another. In these models, disability states were defined by HAQCitation29,32,34 or DAS scoreCitation33 categories. In other analyses, disability was treated as continuous variable (HAQ score) sampled periodically, typically over 6-month intervalsCitation14,15,35,36. Models of abatacept treatmentCitation13, including the current one, are examples of this type of probabilistic HAQ-trend simulation model.

This analysis is methodologically comparable to previous cost-utility analyses of abatacept in patients with an inadequate response to MTX or anti-TNFα drugsCitation13,16, based on efficacy data from the AIM and ATTAIN trialsCitation3,7. The current analysis differs in that it compares abatacept and rituximab, using adjusted responses from their respective clinical trials. In this, as in other probabilistic patient simulation models and in Markov models, HAQ scores were translated into utilities via the relationship between HAQ-DI score and quality of life, measured in this and other cases with the EQ-5DCitation13,14,32,34–36 and elsewhere with the Health Utility IndexCitation15,18. Efficacy and medical costs were also dependent on HAQ-DI scores. Using different measures of cost, efficacy, and utility in the model may have yielded different results. However, the same assumptions were made for both abatacept and rituximab, so that the relative ranking of their incremental CU ratios compared to MTX is less likely to be affected than the absolute values.

The CU model assumed that patients who discontinued abatacept due to lack of efficacy or other reasons would continue to be treated with MTX alone. This assumption may be appropriate in the short term for this patient population (non-responders to conventional DMARDs and TNFα antagonists), though it is unrealistic over patients' lifetimes. Nonetheless, this assumption avoids equally unrealistic assumptions regarding treatment algorithms and their efficacy in these patients. Current guidelines do not address treatment algorithms in patients discontinuing abatacept or rituximabCitation37. As there are no clinical trials directly comparing abatacept and rituximab, an incremental cost-utility ratio for these two agents was not calculated. Instead, incremental cost-utility ratios for each biologic relative to MTX were computed, using a formula that adjusted efficacy of the biologics to the same reference MTX group. As previous authors have noted, such incremental CU ratios do not directly compare one biologic agent with anotherCitation18, but are useful in ranking them relative to MTX.

The results of this analysis rely on the assumption that trends in HAQ-DI score and rates of discontinuation of biologic treatment observed over 6 months in the ATTAIN and REFLEX trials can be extrapolated to the community setting and sustained over the long term. It has been noted that the outcomes of randomized clinical trials for some biologics (specifically, leflunomide and anti-TNFα agents) are better than seen in RA patients in the communityCitation38. Very-long-term studies of abatacept and rituximab have not been carried out, but extensions of clinical trials have provided data up to 5 years for abataceptCitation39–42. These extension studies have provided encouragement that the treatment effects of abatacept are maintained over time. The improvements in the signs and symptoms of RA, in physical function, and in quality of life seen in the double-blind trials were maintained at 5-year follow-upCitation39,40,42, and examination of radiographic data at 2 years suggested that abatacept may have an increasing disease-modifying effect on structural damage over timeCitation41. There are less data available for rituximab. However, data from a 6-month extension of patients who took part in three earlier randomized trials of rituximab indicated that, after an additional course, clinically meaningful improvements in HAQ-DI were sustained, with no new adverse eventsCitation43. A 6-month open-label extension of the REFLEX trial showed that rituximab continued to inhibit the progression of structural joint damage at week 56Citation44. In addition, patients who respond to an initial course of rituximab also respond to later retreatmentCitation23. These extension studies also support the long-term dosing frequencies assumed in the model, which were monthly for abatacept and biannually for rituximab. Hence, patients in the extension studies of abatacept received abatacept every 4 weeksCitation39,40. Dosing of rituximab was at 6-month intervals in the extension studies,Citation23,43 and most patients required retreatment after 6 monthsCitation23. However, long-term observational studies will be necessary to validate these assumptions and determine outcomes in clinical practiceCitation45.

Conclusion

In conclusion, abatacept was estimated to be more cost effective in relation to MTX than rituximab for RA from the perspective of a US third-party payer, based on a threshold of $50,000. These findings were based on two comparable randomized controlled trials. Head-to-head trials and long-term, observational studies will be necessary to verify the results from this analysis.

Acknowledgment

Declaration of interest: This study was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (BMS), Plainsboro, NJ, USA. All authors are employed by BMS Company. The authors are grateful to Julia Vishnevetsky, in collaboration with SCRIBCO, for medical writing assistance. Some of this work was presented at the Annual European Congress of Rheumatology (EULAR), June 14, 2008, Paris, France.

References

- Kvien TK. Epidemiology and burden of illness of rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoeconomics 2004;22(Suppl 1):1-12

- Kremer JM, Dougados M, Emery P, Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with the selective costimulation modulator abatacept: twelve-month results of a phase iib, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2263-2271

- Kremer JM, Genant HK, Moreland LW, Effects of abatacept in patients with methotrexate-resistant active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 20 2006;144:865-76

- Emery P, Fleischmann R, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, The efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate treatment: results of a phase IIB randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1390-1400

- Mease PJ, Revicki DA, Szechinski J, Improved health-related quality of life for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis receiving rituximab: Results of the Dose-Ranging Assessment: International Clinical Evaluation of Rituximab in Rheumatoid Arthritis (DANCER) Trial. J Rheumatol 2008;35:20-30

- Schiff M, Keiserman M, Codding C, Efficacy and safety of abatacept or infliximab vs placebo in ATTEST: a phase III, multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1096-1103

- Genovese MC, Becker JC, Schiff M, Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1114-1123

- Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: Results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2793-2806

- Orencia [package insert]: Bristol-Myers Squibb, 2008.

- Rituxan [package insert]: 2008

- Kobelt G. Thoughts on health economics in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66(Suppl 3):iii35-39

- Drummond MF, Schwartz JS, Jonsson B, Key principles for the improved conduct of health technology assessments for resource allocation decisions. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2008;24:244-258

- Vera-llonch M, Massarotti E, Wolfe F, Cost-effectiveness of abatacept in patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:535-541

- Brennan A, Bansback N, Reynolds A, Conway P. Modelling the cost-effectiveness of etanercept in adults with rheumatoid arthritis in the UK. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:62-72

- Bansback NJ, Brennan A, Ghatnekar O. Cost effectiveness of adalimumab in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:995-1002

- Vera-Llonch M, Massarotti E, Wolfe F, Cost-effectiveness of abatacept in patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1745-1753

- Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:778-799

- Spalding JR, Hay J. Cost effectiveness of tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors as first-line agents in rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoeconomics 2006;24:1221-1232

- Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY. The dimensions of health outcomes: the health assessment questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheumatol 1982;9:789-793

- Choi HK, Seeger JD, Kuntz KM. A cost-effectiveness analysis of treatment options for patients with methotrexate-resistant rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:2316-2327

- Choi HK, Seeger JD, Kuntz KM. A cost effectiveness analysis of treatment options for methotrexate-naive rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2002;29:1156-1165

- Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 1997;35:1095-1108.

- Thurlings RM, Vos K, Gerlag DM, Tak PP. Disease activity-guided rituximab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: the effects of re-treatment in initial nonresponders versus initial responders. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:3657-3664

- Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, Recommendations of the Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA 1996;276:1253-1258

- Halpern EF, Weinstein MC, Hunink MG, Gazelle GS. Representing both first- and second-order uncertainties by Monte Carlo simulation for groups of patients. Med Decis Making 2000;20:314-322

- Goldie SJ. Chapter 15: Public health policy and cost-effectiveness analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2003;102-110

- Stinnett AA, Paltiel AD. Estimating CE ratios under second-order uncertainty: the mean ratio versus the ratio of means. Med Decis Making 1997;17:483-489

- Doan QV, Chiou CF, Dubois RW. Review of eight pharmacoeconomic studies of the value of biologic DMARDs (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. J Manag Care Pharm 2006;12:555-569

- Wong JB, Singh G, Kavanaugh A. Estimating the cost-effectiveness of 54 weeks of infliximab for rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med 2002;113:400-408

- Clark W, Jobanputra P, Barton P, Burls A. Technology assessment report commissioned by the HTA programme on behalf of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence: the clinical and cost-effectiveness of anakinra for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in adults. 2003; http://eprints.bham.ac.uk/32/1/Clark_W,_Anakinra.pdf

- Jobanputra P, Barton P, Bryan S, Burls A. The effectiveness of infliximab and etanercept for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2002;6:1-110

- Kobelt G, Jönsson L, Young A, Eberhardt K. The cost-effectiveness of infliximab (Remicade) in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in Sweden and the United Kingdom based on the ATTRACT study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:326-335

- Welsing PM, Severens JL, Hartman M, Modeling the 5-year cost effectiveness of treatment strategies including tumor necrosis factor-blocking agents and leflunomide for treating rheumatoid arthritis in the Netherlands. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:964-973

- Kobelt G, Lindgren P, Singh A, Klareskog L. Cost effectiveness of etanercept (Enbrel) in combination with methotrexate in the treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis based on the TEMPO trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1174-1179

- Brennan A, Bansback N, Nixon R, Modelling the cost effectiveness of TNF-alpha antagonists in the management of rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Registry. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1345-1354

- Wailoo AJ, Bansback N, Brennan A, Biologic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis in the Medicare program: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:939-946

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:762-784

- Wolfe F, Michaud K. Towards an epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis outcome with respect to treatment: randomized controlled trials overestimate treatment response and effectiveness. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44(Suppl 4):iv18-22

- Genovese MC, Schiff M, Luggen M, Efficacy and safety of the selective co-stimulation modulator abatacept following 2 years of treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:547-554

- Kremer JM, Genant HK, Moreland LW, Results of a two-year follow-up study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who received a combination of abatacept and methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:953-963

- Genant HK, Peterfy CG, Westhovens R, Abatacept inhibits progression of structural damage in rheumatoid arthritis: results from the long-term extension of the AIM trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1084-1089

- Westhovens R, Kremer JM, Moreland LW, Safety and efficacy of the selective costimulation modulator abatacept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving background methotrexate: a 5-year extended phase IIB study. J Rheumatol 2009;36:736-742

- Keystone E, Fleischmann R, Emery P, Safety and efficacy of additional courses of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: an open-label extension analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3896-38108

- Keystone E, Emery P, Peterfy CG, Rituximab inhibits structural joint damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitor therapies. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:216-221

- Pincus T, Yazici Y, van Vollenhoven R. Why are only 50% of courses of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents continued for only 2 years in some settings? Need for long-term observations in standard care to complement clinical trials J Rheumatol 2006;33:2372-2375