Abstract

Background: Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a debilitating disease, accompanied by neurological symptoms of varying severity. Utilities are a key summary index measure used in assessing health-related quality of life in individuals with MS.

Objectives: To provide a systematic review of the literature on utilities of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) and secondary progressive MS (SPMS) patients and to review changes in utilities associated with the increasing neurological disability of different stages of MS, as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS).

Methods: Employing pre-defined search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria, systematic searches of the literature were conducted in EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, the Health Economic Evaluation Database (HEED), and the NHS Economic Evaluations Database (NHS/EED). Proceedings for the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR), the European Society for Treatment and Research in MS (ECTRIMS), the American Society for Treatment and Research in MS (ACTRIMS), and the Latin American Society for Treatment and Research in MS (LACTRIMS) were reviewed in addition to the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence website and the table of contents of PharmacoEconomics and Value in Health.

Results: This review identified 18 studies reporting utilities associated with health states of MS. Utilities ranged from 0.80 to 0.92 for patients with an EDSS score of 1, from 0.49 to 0.71 for patients with an EDSS score of 3, from 0.39 to 0.54 for patients with an EDSS score of 6.5, and from –0.19 to 0.1 for patients with an EDSS score of 9.

Limitations: Several of the studies reviewed relied on data from patient organizations, which may not be fully representative of the general patient populations. Additionally, the majority of the studies relied on retrospective data collection.

Conclusions: Utilities decrease substantially with increasing neurological disability. Cross-country differences are minimal with utility scores following a similar pattern across countries for patients at similar disease severity levels. This consistency in findings is noteworthy, as there is a reliable evidence base for selecting utility values for economic evaluation analyses. However, more research is needed to explore potential differences in utilities between RRMS and SPMS patients.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a debilitating disease, accompanied by neurological symptoms of varying severity, which over many years can result in chronic disability with a major impact on the quality of life and economic activity of patientsCitation1. For approximately 80% of patients, the disease progresses from an episodic disorder (relapsing-remitting MS [RRMS]) to a more progressive state (secondary progressive MS [SPMS]). RRMS is characterized by unpredictable relapses and prolonged remission, while SPMS is characterized by a continuous neurologic degeneration with or without superimposed relapses following RRMS. Once MS is in the progressive phase, it continues to worsen independently of attacks, whereas in the RRMS phase, attacks are followed by remissionCitation2. For a small group of patients, MS progresses from onset with or without occasional plateaus or temporary minor improvements (primary progressive MS [PPMS]).

MS has a substantial negative impact on the quality of life of patients, caregivers, and familiesCitation3. Relapses (as defined by the occurrence of a new neurological symptom or worsening of an old one, with an objective change in functional system scale scores, lasting at least 24 hours, without fever, and which followed a period of clinical stability or of improvement of at least 30 daysCitation4) may result in hospitalization and be associated with a level of disability that disrupts work, social, and family lifeCitation1,5–7. Even in early stages, MS can restrict professional and personal activities. Symptoms such as weakness, fatigue, and speech problems can result in depression and isolation and further contribute to a reduced quality of lifeCitation8.

Disability in MS is commonly quantified in half-point increments using a clinician-measured scale, the Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)Citation9. The EDSS, an expanded version of the Disability Status Scale (DSS), quantifies disability in a number of Functional Systems (FS) and allows neurologists to assign a Functional System Score (FSS) using a 0–10 scale. The Functional Systems are pyramidal, cerebellar, brainstem, sensory, bowel and bladder, visual, and cerebral. EDSS scores of ≤6.5 refer to people with MS who are ambulatory whereas EDSS scores of > 6.5 are defined by the impairment to ambulation. Therefore, this scale measures disease progression predominantly by focusing on deficits in ambulation, but does not assess many of the other disease aspects that significantly impact patient's quality of life.

Specific disability assessment instruments can be used to evaluate physical symptoms; however, measures that focus on different aspects of physical disability domains are seldom adequate to summarize the burden of MS on the overall quality of life of patients and their familiesCitation10. These scales fall short of measuring quality of life domains that are particularly important for patients, such as mental health and vitality. Hence, a summary index measure of health-related quality of life such as health utility may better summarize the overall effects. Utility can be defined as the preference of patients, caregivers, and/or the general population for given states of healthCitation11. Utility is expressed as a value on a scale ranging from 0 (dead) to 1 (full health), sometimes allowing the expression of a value lower than 0 (for health states considered to be worse than death).

In addition to providing an important summary index measure of health-related quality of life, utilities have become essential parameters in healthcare priority settings. Economic evaluations play an ever-increasing role in resource allocation decisions, and agencies responsible for reimbursement decisions, such as the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK, recommend using utilities as the health-related quality of life component of the quality-adjusted life year (QALY) measure. Combining longevity and quality of life domains into a single outcome measure that is comparable across interventions and diseases, QALYs are the standard outcome measures in health economic evaluations. Given that health utilities are one of the key factors in calculating QALYs, they have a major impact on the results of many health technology appraisals that determine the reimbursement status of new treatments and technologiesCitation12.

Because of the increasing relevance of utilities in health economic evaluations, there has been a growing body of literature estimating the health-related quality of life of MS patients in the form of utilities. The primary objective of this study is to provide a comprehensive and systematic review of this literature by reporting the health utilities of MS patients. The secondary objective is to review how health utilities change with increasing neurological disability, as measured by the EDSS, associated with different stages of MS.

Methods

Literature search strategy

The literature search was conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, the Health Economic Evaluation Database (HEED), and the NHS Economic Evaluations Database (NHS/EED). EMBASE.com was used as the platform to search both MEDLINE and EMBASE databases. All databases were searched from January 1, 1993, to July 25, 2009. In addition, proceedings for the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR), the European Society for Treatment and Research in MS (ECTRIMS), the American Society for Treatment and Research in MS (ACTRIMS), and the Latin American Society for Treatment and Research in MS (LACTRIMS) were reviewed for potentially relevant abstracts going back 3 years (from 2005 to 2008). A search was conducted on the UK NICE website for unpublished quality of life information as a part of health technology assessment (HTA) references (latest search date: 25 July 2008). A manual search of the table of contents of PharmacoEconomics and Value in Health was also performed going back two years (latest search date: 25 July 2008). Bibliographies of review articles and potentially relevant primary studies were evaluated to obtain additional relevant references.

With the understanding that health utility information may also be provided as a part of cost-of-illness studies as well as cost-effectiveness studies, the search strategy included three sets of terms: (1) terms to search for patients with MS; (2) terms to search for cost of MS and cost-effectiveness of MS treatments; and (3) terms to search for health utilities associated with MS health states. The search terms used are listed in Appendix 1.

Abstracts identified were manually reviewed and assessed for potential inclusion in the review according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Appendix 2). Full articles of potentially relevant abstracts were obtained for final assessment. Table shells for data extraction were predefined.

Selection criteria

Studies were included if they reported health utilities associated with various MS health states. Study populations consisted of RRMS and SPMS patients, patients with relapsing forms of MS, or patients who were at risk of developing clinically definite MS. This review excluded studies with a primary patient population of PPMS patients given the dramatically different course of disease experienced in these patients. The search was limited to original research articles published in English. Studies were also excluded if they were editorials or were published before 1993.

Data extraction

An electronic data extraction form was created in Microsoft Excel. Data extraction was independently assessed by a second reviewer.

Background on the preference elicitation methods reviewed

There are a number of techniques available for valuing health states and calculating utilities. For indirectly measuring utilities, three main health utility measures exist: the EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D), the Health Utility Index Mark 3 (HUI3), and the Short Form-6D (SF-6D). The EQ-5D is a commonly used patient-based instrument for deriving utilities associated with various health conditions. The EQ-5D is a generic quality-of-life measure consisting of five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) where each dimension has three different levels of severity (1 = no problem, 2 = moderate problem, 3 = severe problem), producing a total of 243 possible health states, where higher scores of individual questions indicate more severe or frequent problemsCitation13. A tariff representing a single index value for each of the states is then applied to express the value of differences between health states in a descriptive classification to derive utilities.

The Health Utility Index (HUI) is also a preference-based instrument used for the purposes of deriving health utility scores. The health states in the latest version, HUI Mark 3 (HUI3), represent patient responses in eight health dimensions: vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, cognition, and painCitation14. The HUI3 does not inquire about functioning or role limitations with the understanding that these may be influenced by factors such as the physical or social environmentCitation15. There is a multiplicative multi-attribute utility function for the HUI3 system, which generates utility scores for HUI3 health states. The HUI3 scoring function is based on preference measurements obtained from a random sample of the general population in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Although not specifically developed as a utility instrument, the SF-6D is another preference elicitation instrument commonly used to derive utilities. The SF-6D health states represent physical functioning, role limitations, social functioning, pain, mental health, and vitalityCitation16. These symptom domains have been identified both by MS patients (mental health, vitality) and by MS clinicians (physical functioning, physical role limitations) as important determinants of quality of lifeCitation10. The SF-6D comes with a set of preference weights obtained from a sample of the general population in the UK to generate health utility values.

Results

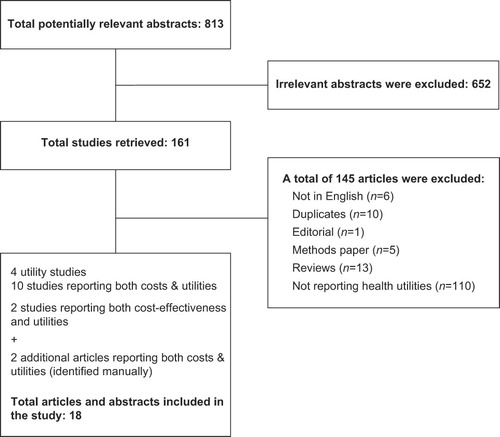

shows the flowchart for the identification of studies with reasons for exclusion. Overall, the search strategy identified 813 abstracts from studies with the potential for inclusion in this review. Based on the abstracts, 161 articles were ordered and manually reviewed. Of these 161 articles, 18 were included in this study.

The EMBASE/MEDLINE search identified 361 abstracts from studies with the potential for inclusion in this review. Based on the abstracts, 77 articles were ordered and manually reviewed. Of these 77 studies, 15 met the eligibility criteria for our study. The PsycINFO search identified 306 abstracts, 24 of which were ordered and manually reviewed. None of these studies were included because they did not meet the eligibility requirement. The NHS/EED search identified 92 studies, 31 of which were retrieved in full text and reviewed. One of these full-text articles was included. Seventeen potentially relevant abstracts were identified from HEED. One article from HEED was retrieved for detailed evaluation, but this article was not included in the final review. Eighteen abstracts from ISPOR were reviewed, and none were included. The ECTRIMS/ACTRIMS/LACTRIMS search identified 15 additional poster abstracts, none of which were included. One HTA was identified from the UK NICE website. The NICE HTA report was not included in the final review since it was a guidance report and it did not include utility findings associated with MS. Three potentially relevant abstracts were identified from the manual search of table of contents of PharmacoEconomics and Value in Health; however, these studies were not included in the final review since all three were duplicates. Two articles were identified from the manual search of bibliographies of review articles. Both of these were included in the final review.

This review identified four utility studies, 12 cost-of-illness studies reporting both costs and utilities, and two studies reporting both cost-effectiveness and utilities.

Study characteristics

Four of the included studies were from the UKCitation17–20, whereas three were from CanadaCitation21–23, two from GermanyCitation24,25, two from SwedenCitation26,27, one from AustriaCitation28, one from BelgiumCitation29, one from ItalyCitation30, one from the NetherlandsCitation31, one from SpainCitation32, one from SwitzerlandCitation33, and one from the USCitation34.

Patient population characteristics in terms of disease type and severity were similar among the majority of the included studies (). Thirteen studies included a mixed patient population consisting of both RRMS and SPMS patients. Two studies included only RRMS patientsCitation19,34, whereas one study included only SPMS patientsCitation20. Two studies did not report whether patient populations consisted of RRMS, SPMS, or both types of patients. A considerable portion of patients in the study samples did not know or did not answer the question regarding the type of MS, reflecting the difficulty in defining the disease course and conversion from RRMS to SPMS. The majority of studies that reported the neurological disability distributions of their patient populations included patients with moderately severe disease with EDSS scores between 4 and 6. With a mean EDSS score of 2.7, the disease severity of the patient population in the study by Prosser et al was significantly lower (less disabled) than the rest of the studiesCitation34.

Table 1. Summary of included study characteristics.

The percent of MS patients receiving disease-modifying drugs varied significantly and ranged from approximately 21% of the study population in the UKCitation19 to about 52% in SpainCitation32. Approximately 36% of patients in the Netherlands received disease-modifying drugs as compared to 38% of patients in SwitzerlandCitation33, 39% of patients in GermanyCitation24, and 40% in AustriaCitation28. Between 40% and 50% of patients in BelgiumCitation29, ItalyCitation30, and SwedenCitation26,27 reported that they were on disease- modifying drug treatment.

Fourteen studies used EQ-5D as the main preference elicitation instrument to derive utilities. One study compared EQ-5D to SF-6D and HUI3Citation23. Two studies used the HUICitation21,22. The study by Prosser et al used the preference elicitation software, U Titer II, to derive utilities with the standard gamble methodCitation34. In all studies where the EQ-5D was used, the answers received from patients were translated into utilities via a scoring algorithm established with the UK general population by using the time trade-off techniqueCitation35. All studies reported community-based preference scores except for one that also reported patient preferences.

All 14 studies that used EQ-5D as the primary preference elicitation instrument collected information on patient preferences for various MS states using postal surveysCitation17,18,20,22,24–33. The remaining four studies relied on clinic-based data collection techniquesCitation19,21,23,34. The majority of included studies did not report whether proxy respondents took part in the data collection process. Only one of the studies that relied on mail-in surveys explicitly stated that all information collected in the postal survey was either self-reported or reported by a proxy respondentCitation22.

Comparison of preference elicitation instruments

The study by Fisk et al evaluated the practical application and psychometric properties of three health utility measures by using self-assessed versions of SF-6D, HUI3, and EQ-5D to derive utilities of MS health statesCitation23. Their study demonstrated that all three instruments were generally feasible and reliable and were able to distinguish between the groups of mildly, moderately, severely, and very severely disabled patients. However, HUI3 demonstrated highest concordance with the EDSS across the full range of neurological disability even though EDSS is not likely to fully reflect health impairments in other domains.

Health utilities

Sixteen studies reported health utilities by EDSS scores (). Health utilities ranged from 0.80 to 0.92 for patients with an EDSS score between 0 and 1. For EDSS 2 patients, health utilities ranged from 0.68 to 0.84 whereas they ranged from 0.49 to 0.71 for EDSS 3 patients. They ranged from 0.56 to 0.71 for EDSS 4 patients, from 0.52 to 0.97 for EDSS 5 patients, from 0.38 to 0.54 for EDSS 6.5 patients, and from 0.27 to 0.45 for EDSS 7 patients. Patients with an EDSS score between 8 and 9 had health utilities ranging from –0.19 to 0.70. Although EDSS categories varied considerably among included studies, a clear inverse relationship between health utilities and EDSS scores was observed.

Table 2. Health utilities by EDSS scores.

All included studies reported low utility values associated with MS health states. The study by Jones et al showed that MS patients reported significantly lower utility values compared to people without MSCitation22. After adjusting for age, sex, education, marital status, social assistance, and a number of medical conditions other than MS, the overall HUI3 score for MS patients was 0.58 as compared to 0.84 for the general population. Therefore, the mean difference in overall utility scores between respondents with and without MS was 0.25.

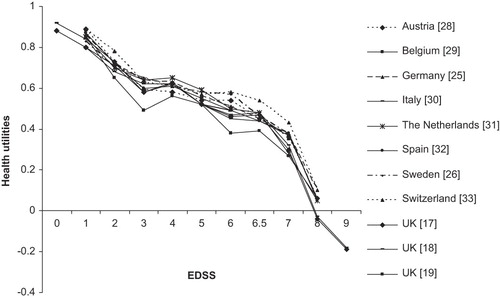

When utilities associated with similar EDSS categories were compared between countries with EQ-5D as the preference elicitation method, it was clear that utilities followed a similar pattern across countries, illustrating a similar correlation between neurological disability and quality of life irrespective of location ().

Figure 2. Health utilities by EDSS scores reported in studies using EQ-5D as the preference elicitation instrument. EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale.

Only one study reported utilities by disease type. The study by Orme et al showed that the health utility of SPMS patients was 0.045 points lower than it was for RRMS patientsCitation17. Twelve studies reported the utility loss associated with a relapse (). The utility loss associated with a relapse varied significantly and ranged from 0.029 in Sweden26 to 0.8 in Switzerland and the UKCitation19,33. The study by Orme et al showed that receiving treatment was not significantly associated with an improvement in utility valuesCitation17.

Table 3. Health utility loss due to a relapse.

The study by Forbes et al stratified utility values by postal ambulation scale score (indication of current level of ambulation on a postal ambulation scale based on the scale of McAlpine and Compston)Citation36 and showed that unrestricted patients (able to walk unaided for unlimited distances) had a mean utility score of 1.0, whereas patients who could walk up to 500 meters (m) unaided had a mean utility score of 0.620Citation20. The mean utility score was 0.643 for patients who were able to walk up to 250 m unaided, 0.369 for patients who could walk indoors with assistance, 0.015 for wheelchair-dependent patients, and –0.260 for patients who were restricted to bed.

One study compared health utilities reported by MS patients and community responders. While the MS patients were from a clinic setting, the community responders consisted of residents of a large apartment complex in San Diego, CA. The study by Prosser et al showed that patients assigned higher utilities (better health) for both MS health states and treatment states than community respondentsCitation34. The ratings became more disparate as health states worsened. For an EDSS score of 2.5, mean utilities were 0.08 higher for patients than for community responders. This difference in mean utilities was 0.04 for EDSS 3.5, 0.15 for EDSS 5, 0.09 for EDSS 6, and 0.21 for EDSS 8 with higher utility values coming from the patients. The utilities obtained from community responders correspond to those from other studies that used health status instruments to generate utility weights based on community preferences.

Discussion

This systematic review of the literature identified 18 studies. The majority of the studies were from Europe whereas four were from North America, not necessarily reflecting the predominance of studies in countries with a high prevalence of MSCitation37, but perhaps demonstrating the greater emphasis on research related to utilities in countries with advanced health technology appraisal requirements. This review highlighted the severity of impairment expressed by people with MS by showing that MS had a significant impact on the health utility of patients. There was a dramatic decrease in utility associated with an increase in disease severity as measured by EDSS scores. Some countries showed significant variations in utility scores associated with different severity levels: In Belgium, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland, for instance, utility scores decreased dramatically from above 0.8 to less than 0.1 with increasing disease severityCitation29. At very high EDSS scores, patients in the UK reported health utility values that were worse than deathCitation17,18. When the same preference elicitation instruments were used, cross-country differences were minimal, with utility scores following a similar pattern across countries for patients at similar severity levels. This consistency in the findings is noteworthy since it may not only indicate the robustness of the reported estimates, but also result in consistent findings when utility values from different settings are selected for health economic evaluation analyses.

Although the study by Orme et al suggested that type of disease (such as SPMS and RRMS) had an effect on the quality of life of people with MSCitation17, there was a paucity of evidence to infer on potential differences in health utilities between RRMS and SPMS patients when taking into account EDSS score. The majority of the included studies suggested that the variation in health utilities appears to be primarily explained by the severity of disability and potentially because generic instruments may have low coverage of quality of life domains relevant to people with MS. Additionally, many studies relied on patients to classify their disease course, which as many studies noted, was a difficult task for patientsCitation29. There is also increasing discussion among MS clinical experts that the classification between RRMS and SPMS is artificial and these types of disease are simply part of the full spectrum of MS. Utilities were hence not analyzed by disease course in most studies. However, it is essential to note that more research is urgently needed to investigate the potential differences (or lack thereof) in health utilities between SPMS and RRMS patients, as this classification continues to form the basis of economic evaluations of disease modifying treatments used in MS.

Another important finding was that health utilities decreased significantly during relapses. However, the decrement in utility values associated with a relapse varied across studies. This variability may be because the effect of a relapse was not the same at different levels of disease severity. As the study by Kobelt et al suggested, it is possible that exacerbations had a stronger impact on patients with limited disability and relapsing diseaseCitation38. Another factor that could potentially contribute to this variability is the different recall periods used in the studies. The majority of studies asked the patients to rate the relapse within the last 3–6 months; however, a large number of patients were unsure or did not answer the question regarding relapse occurrence, indicating the difficulty for patients to define an exacerbation or to remember the eventCitation26. Therefore, a number of studies did not report the proportion of patients who experienced relapses in addition to the severity and duration of relapses. Given these methodological inconsistencies, as the study by Orme et al stated, the utility loss associated with a relapse cannot be accurately estimated based on the available information and a longitudinal study would be required to determine the total utility loss associated with a relapseCitation17.

There are a number of limitations with this review. In the majority of the included studies, the study samples came from patient organizations (organizations that provide support services to patients with MS), which were most likely not fully representative of the general patient population. Indeed, most studies acknowledged that there was a slight over-representation of patients with moderate and severe disease with EDSS scores between 4 and 6. As the study by Kobelt et al indicatedCitation29, it is possible that patients joining associations were often more advanced in their disease, since it may take a number of years from diagnosis to active involvement in such associations and the need to exchange experiences with other patients. However, it is important to note that this review was not likely to be biased by this over-representation since, where possible, health utilities were reported by EDSS scores instead of providing the mean value for each study.

The majority of the included studies relied on retrospective data collection. This design potentially affected the reliability of the findings in the included studies. Given the importance of the interviewing technique, the study protocol, and the design of questionnaires in utility assessment studies, it is difficult to assess whether bias was introduced in assessing the quality-of-life domains of MS patients and, if even it was, how it affected the findingsCitation39. Additionally, due to the nature of the postal questionnaire studies, respondents in most of the studies were self-selected and a ‘volunteer effect’ might apply to this review; the effect of self-selection on the results reviewed in this study is not known.

All included studies that reported utilities associated with MS health states based their analyses on choice-based methods such as standard gamble and time trade-off, which are techniques favored by health economistsCitation40. This choice of valuation is important because different techniques have been shown to generate different values for the same health statesCitation41. Most studies employed the EQ-5D as the preference elicitation tool. However, there is emerging literature that suggests that the EQ-5D may have low coverage of quality-of-life domains relevant to people with MSCitation42. It is likely that an alternative instrument to the EQ-5D, such as the HUI3which covers more quality-of-life domains relevant to people with MS, would provide different utility values in the included studiesCitation17. The HUI3 assesses neurological function in addition to emotional health and also incorporates patients' perspectives of their health status. As the study by Fisk et al showed, the HUI3 demonstrated the highest concordance with EDSS scores across the full range of neurological disability associated with MSCitation23. Their study concluded that only the HUI3 consistently performed well as a clinically relevant measure for pharmacoeconomic studies of MS treatments.

Although the use of the proxy version of mail-in surveys was not specifically stated in the majority of the studies, it is possible that bias may have been introduced in higher disease severity levels. This is mainly due to different informants generating different values for the same health states with patients assigning higher utilities for health states when compared to community respondentsCitation43. Similarly, the only study that reported both patient and community-based utilities for MS health states showed that patients tend to assign higher utilities (better health) to an impaired health state they have experienced as compared with respondents who have not experienced the health stateCitation34.

All of the included studies utilized generic preference-based measures using data on health-related quality of life that have been obtained from patients and then scored using values obtained from members of the general population. As reviewed in the article by BrazierCitation40, there has been debate in the literature as to whether patient values should be used to score these states instead of using values from the general public. This is an important distinction because patients tend to give higher values (better health) to the same health states as compared to the general public, mainly due to the fact that patients tend to adjust to their health states.

Conclusions

This review highlighted the debilitating impact of MS on the quality of life of patients. Utilities decrease substantially with increasing neurological disability and the variation in health utilities appears to be mainly explained by the severity of the disability, as measured by EDSS scores. Although there were methodological and reporting-related inconsistencies in health utilities associated with relapses, utilities appear to decrease during relapse phases of the disease. This review highlighted the need for more research in the MS health utility area. Particularly, given the relevance of the RRMS/SPMS classification in economic evaluation analyses, there is a clear need to investigate the impact of different types of MS on health utilities.

Transparency

Declaration of funding:

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company.

Declaration of financial/ other relationships:

J. B. and A. D. are full-time employees of Eli Lilly and Company. H. N. and R. F. are employees of the United BioSource Corporation who were paid consultants to Eli Lilly and Company in connection with the development of this systematic review and manuscript.

The JME peer reviewers 1 and 2 have not received an honorarium for their review work on this manuscript. Both have disclosed that they have no relevant financial relationships.

References

- De Judicibus MA, McCabe MP. The impact of the financial costs of multiple sclerosis on quality of life. Int J Behav Med 2007;14:3-11.

- Vollmer T. The natural history of relapses in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2007;256:S5-13.

- Aronson KJ. Quality of life among persons with multiple sclerosis and their caregivers. Neurology 1997;48:74-80.

- Schumacher GA, Beebe G, Kibler RF, Problems of experimental trials of therapy in multiple sclerosis: report by the panel on the evaluation of experimental trials of therapy in multiple sclerosis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1965;22:552-568.

- Yorkston KM, Johnson K, Klasner ER, Getting the work done: a qualitative study of individuals with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 2003;25:369-379.

- McCabe MP, De Judicibus M. The effects of economic disadvantage on psychological well-being and quality of life among people with multiple sclerosis. J Health Psychol 2005;10:163-173.

- Stolp-Smith KA, Atkinson EJ, Campion ME, Health care utilization in multiple sclerosis: a population-based study in Olmsted County, MN. Neurology 1998;50:1594-1600.

- Ford HL, Gerry E, Johnson MH, Health status and quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 2001;23:516-521.

- Miltenburger C, Kobelt G. Quality of life and cost of multiple sclerosis (Provisional record). Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2002;104:272-275.

- Rothwell PM, McDowell Z, Wong CK, Doctors and patients don't agree: cross sectional study of patients' and doctors' perceptions and assessments of disability in multiple sclerosis. Br Med J 1997;314:1580-1583.

- Drummond M, Sculpher M, Torrance G, Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes, 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- NICE. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. [online]. 2008. Available from URL: http://www.nice.org.uk/media/B52/A7/TAMethodsGuideUpdatedJune2008.pdf [Accessed 2008 January 29].

- EuroQol Group. EQ-5D: A standardised instrument for use as a measure of health outcome. [online]. Available from URL: http://www.euroqol.org/ [Accessed 2008 8 December].

- Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance G, The Health Utilities Index system for assessing health-related quality of life in clinical studies. Ann Med 2001;33:375-384.

- Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance G, Multiplicative multi-attribute utility function for the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3) system: a technical report: McMaster University, 1998.

- The University of Sheffield, Department of Health Economics and Decision Science. About the SF-6D. [online]. 2008. Available from URL: http://www.shef.ac.uk/scharr/sections/heds/mvh/sf-6d [Accessed 2008 8 December].

- Orme M, Kerrigan J, Tyas D, The effect of disease, functional status, and relapses on the utility of people with multiple sclerosis in the UK. Value Health 2007;10:54-60.

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, Costs and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in the United Kingdom (Brief record). Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:S96-104.

- Parkin D, Jacoby A, McNamee P, Treatment of multiple sclerosis with interferon (beta): an appraisal of cost-effectiveness and quality of life. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68: 144-149.

- Forbes RB, Lees A, Waugh N, Population based cost utility study of interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Br Med J 1999;319:1529-1533.

- Grima DT, Torrance GW, Francis G, Cost and health related quality of life consequences of multiple sclerosis (Provisional record). Multiple Sclerosis 2000;6:91-98.

- Jones CA, Pohar SL, Warren S, The burden of multiple sclerosis: a community health survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:1.

- Fisk JD, Brown MG, Sketris IS, A comparison of health utility measures for the evaluation of multiple sclerosis treatments. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:58-63.

- Kobelt G, Lindgren P, Smala A, Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. An observational study in Germany. HEPAC Health Economics in Prevention and Care 2001;2:60-68.

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, Costs and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in Germany. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:534-544.

- Berg J, Lindgren P, Fredrikson S, Costs and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in Sweden. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:S75-85.

- Henriksson F, Fredrikson S, Masterman T, Costs, quality of life and disease severity in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study in Sweden. Eur J Neurol 2001;8:27-35.

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, Costs and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in Austria. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7: 514-523.

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, Costs and quality of life for patients with multiple sclerosis in Belgium. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:S24-33.

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, Costs and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in Italy. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:S45-54.

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis in The Netherlands. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:S55-64.

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, Costs and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in Spain. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:S65-74.

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, Costs and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in Switzerland. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:S86-95.

- Prosser LA, Kuntz KM, Bar-Or A, Patient and community preferences for treatments and health states in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2003;9:311-319.

- Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, A Social Tariff for EuroQol: Results from a UK General Population Survey. York, UK: Center for Health Economics, University of York, 1995.

- McAlpine D, Compston N. Some aspects of the natural history of disseminated sclerosis. QJM 1952;21:135-167.

- Atlas of MS Database. Global Prevalence of MS [online]. 2009. Available from URL: http://www.atlasofms.org/index.aspx [Accessed 2009 March 11].

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis in Europe: method of assessment and analysis (provisional record). Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:S5-13.

- Coughlin SS. Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol 1990;43:87-91.

- Brazier J. Valuing health states for use in cost-effectiveness analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:769-779.

- Dolan P, Sutton M. Mapping visual analogue and standard gamble utilities. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:1519-1530.

- Gruenewald DA, Higginson IJ, Vivat B, Quality of life measures for the palliative care of people severely affected by multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler 2004;10:251-255.

- Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Cost Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Appendix 1. Search limits and terms

Search Limits

i. 1993 to July 25, 2009

Search terms

i. Quality-adjusted life years

ii. Utilities

iii. Quality of life

iv. Health related quality of life

v. Health status

vi. Time trade off

vii. Standard gamble

viii. Visual analogue scale

ix. Multiple sclerosis

x. Myelitis, transverse

xi. Demyelinating diseases

xii. Encephalomyelitis

xiii. Device

xiv. Neuromyelitis optica

xv. Myelooptic neuropathy