Abstract

Aim: To determine current treatment patterns for infants with cow milk allergy (CMA) and the associated resource implications and budget impact, from the perspective of the UK's National Health Service (NHS).

Methods: A computer-based model was constructed depicting current management of newly-diagnosed infants with CMA derived from patients suffering from this allergy in The Health Improvement Network (THIN) Database. The model spanned a period of 12 months following initial presentation to a general practitioner (GP) and was used to estimate the 12-monthly healthcare cost (at 2006/07 prices) of treating an annual cohort of 18,350 infants from when they initially present to their GP.

Results: Patients presenting with a combination of gastrointestinal and atopic symptoms accounted for 59% of all patients. From the initial GP visit for CMA it took a mean 2.2 months to be put on diet, although treatment varied according to presenting symptoms. A total of 60% of all infants were initially treated with soy, 18% with an extensively hydrolysed formula and 3% with an amino acid formula. A mean 9% of patients remained symptomatic on soy and 29% on an extensively hydrolysed formula. The total cost of managing CMA over the first 12 months following initial presentation to a GP was estimated to be £1,381 per patient and £25.6 million for an annual cohort of 18,350 infants.

Limitations: Patients were not randomised to treatment and resource use was not collected prospectively. Nevertheless, 1,000 eligible patients have been included in the analysis, which should be a sufficiently large sample to accurately assess treatment patterns and healthcare resource use in actual clinical practice. The diagnosis of CMA may not be secure in all cases. Nevertheless, patients were diagnosed as having CMA by a clinician and have been managed by their GP as if they had CMA.

Conclusion: CMA imposes a substantial burden on the NHS. Any strategy that improves healthcare delivery and thereby shortens time to treatment, time to diagnosis and time to symptom resolution should potentially decrease the burden this allergy imposes on the health service and release resources for alternative use.

Introduction

Cow milk allergy (CMA) is an adverse reaction to protein in cow's milk involving the immune systemCitation1. Its incidence in infancy in western industrialised countries has been estimated at 2–3%Citation2. CMA generally develops within the first few months of life and symptoms can appear either very quickly after feeding (rapid-onset) or not until 7–10 days after consuming cow milk protein (slower-onset)Citation3–5. The slower-onset reaction is more common and symptoms may include loose stools (possibly containing blood), gastro-oesophageal reflux, gagging, refusing food, irritability or colic, skin rashes and failure to thrive. This type of reaction is more difficult to diagnose because the same symptoms may occur with other health conditions. Most children will outgrow this form of allergy by the second year of life. Rapid-onset reactions come on suddenly with symptoms that can include irritability, vomiting, wheezing, swelling, hives, other itchy bumps on the skin, and bloody diarrhoea. In rare cases anaphylaxis can occur. However, this is more common with peanut, nut, and shellfish allergiesCitation2. Several tests can be used to inform a diagnosis of milk allergy, including a stool test, RAST test, skin prick test, and patch testingCitation5,6. However, these tests may yield false positives or false negatives.

Clinical nutrition preparations for infants with CMA include soy-based milk, extensively hydrolysed formulas (eHF) and amino acid formulas (AAF). The clinical properties of soy, eHF and AAF have been reviewed elsewhereCitation7–12 so are only briefly described here. Soy-based formulas contain proteins found in soybeans, but the same vitamins and minerals as those found in cow's milk-based formulasCitation7. Extensively hydrolysed formulas (eHF) contain whey- or casein-based milk proteins which have been pre-digested, making them less allergenic than the whole proteins contained in regular formulasCitation8. Elemental formulas, such as Neocate which contains 100% free amino acids and is manufactured in a milk protein-free environment, are not allergenicCitation9–11. Partially hydrolysed formulas are not recommended for use in infants with CMA since they can provoke a significant allergic reactionCitation12.

Mothers of affected infants who are being breastfed are advised to eliminate dairy products from their diet under the close supervision of a dietician, because a strict diet must be followed to ensure adequate intake of nutrients while eliminating cow milk protein. However, in practice, this was not always done. Guidelines in many European countries, Australia and New Zealand recommend mothers of formula-fed infants to feed either a soy protein-based formula or an eHF to those > 6 months of age, but to initially feed only an eHF to those < 6 months of age. Those infants who cannot tolerate soy would generally be switched to an eHF and those who cannot tolerate an eHF would generally be switched to an AAF.

Food allergy represents an important source of patient morbidity and healthcare utilisation. Nevertheless, the literature search did not find any health economic studies on CMA, apart from previous studies conducted by the authors in Finland and AustraliaCitation13,14. The aim of this study was to determine (1) how infants with CMA are managed in clinical practice in the UK and how long it takes to achieve symptom resolution, and (2) the resource implications and budget impact of current clinical practice for managing CMA, from the perspective of the National Health Service (NHS).

Methods

The Health Independent Network Database

The Health Independent Network (THIN) database contains computerised information on 5 million anonymised patients entered by GPs from 300 general practices from across the UK using the Vision Practice Management SoftwareCitation15. The computerised information includes demographics, details from GPs' visits, specialists' referrals, other clinician visits, hospital admissions, laboratory tests and prescriptions issued by GPs, which are directly generated from the computer. The Read classification is used to code specific diagnoses, and a drug dictionary based on data from the Multilex classification is used to code drugs. The patient data within the database is representative of the entire UK population and each NHS regionCitation15.

Study population

The study population was 1,000 randomly selected infants in the THIN database who had at least one selected CMA Read code in their medical history and who were < 1 year of age at first code entry and received at least one prescription for a clinical nutrition preparation. Patients had to be registered with their practice for at least 1 year after the first code entry, otherwise they were excluded. There were no other inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval to use patients' records from the THIN database for this study was obtained from The London Multicentre Research Ethics Committee.

Study variables

Information extracted from patients' records included patients' age, sex, diagnosis, other symptoms and morbidities, and duration of symptoms. Community-based and secondary care healthcare resource use attributable to CMA over a period of 12 months following initial presentation to a GP was also extracted. Patients were stratified according to their presenting symptoms and outcomes and resource use were quantified for each symptomatic group.

Health economic modelling

A computer-based model was constructed, depicting the current management of 1,000 newly-diagnosed infants < 1 year of age with CMA over the first 12 months following initial presentation to a GP. Within the model patients were stratified according to whether they presented with eczema and gastrointestinal symptoms (GI), GI symptoms alone, eczema alone or urticaria with or without other symptoms. Unit resource costs at 2006/07 pricesCitation16–19 () were applied to the resource utilisation estimates within the model in order to estimate the mean healthcare costs and consequences of current clinical practice for CMA, from the perspective of the UK's NHS.

Table 1. Unit costs at 2006/07 prices.

Sensitivity analyses

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were undertaken using second-order Monte Carlo simulations of the patient cohort (10,000 iterations of the model) by simultaneously varying the probabilities, resource use values and unit costs within the model. The probabilities were varied randomly according to a beta distribution using the standard deviation around the mean values in the data set. The resource use estimates and unit costs were varied randomly according to a log-normal distribution using the standard deviation around the mean values in the data set. Additionally, deterministic sensitivity analyses were performed to assess how the costs and consequences of the different treatment strategies would change by varying different assumptions in the model.

Results

Patient characteristics in the THIN dataset

The incidence of GP-diagnosed CMA in the THIN database was estimated to be 1%. The majority of patients in the THIN data set obtained for this study first presented to their GP between 2001 and 2006, but there was no difference in resource use or outcomes irrespective of when they presented. At the time of presentation to a GP, the patients' mean age was 3.2 (95% CI: 3.0; 3.4) months () and 45% were female. Patients presenting to their GP with a combination of eczema and GI symptoms accounted for 59% of all patients, whereas those with urticaria and associated symptoms, such as lip swelling and hives, accounted for < 10% of all patients. A description of patients' symptoms on presentation to their GP is summarised in .

Table 2. Characteristics of CMA patients in the data set.

Treatment of CMA

Treatment of CMA varied according to presenting symptoms. The number of patient pathways for each symptomatic group ranged from as little as one for those presenting with anaphylaxis to as many as 16 for those presenting with a combination of eczema and GI symptoms.

It took a mean 2.2 (95% CI: 2.0; 2.3) months from initially seeing a GP before a patient received their first prescription for a first clinical nutrition preparation (). During that time, some patients received prescriptions for GI drugs and/or topical dermatologicals and/or an antihistamine. Additionally, 75% of patients with anaphylaxis were prescribed an Epipen ().

Table 3. Clinician visits (95% confidence limits in parentheses).

Table 4. Prescribed treatments to CMA patients in the THIN data set.

Soy was the first choice of treatment for the majority of infants (). However, 56% of infants in the THIN data set were < 6 months of age at the start of their treatment and contrary to guidelinesCitation20, 76% of them were initially prescribed soy by their GP, whereas 21% were initially treated with an eHF and 3% with an AAF. Patients' initial diet is summarised in .

Patients were considered to be intolerant to a particular formula if symptoms persisted and the diet was subsequently changed by a GP or specialist. A mean 9% of patients in the data set were intolerant to soy and 29% were intolerant to an eHF (). However, a mean 20% of patients were intolerant to a whey-based eHF and a mean 32% to a casein-based eHF. In particular, patients presenting with GI symptoms were more likely to be intolerant to a casein-based eHF whereas those with dermatological symptoms (i.e. eczema or urticaria) were more likely to be intolerant to a whey-based eHF.

Table 5. Intolerance to different clinical nutrition preparations, stratified by presenting symptoms.

Of the 9% of patients who were intolerant to soy, 89% were switched to an eHF and the remainder to an AAF. Of the 29% of patients who were intolerant to an eHF, 28% were switched to soy, 28% to an AAF and 45% were switched to another eHF.

In all, 42% of all patients were seen by a hospital clinician (), who changed the clinical nutrition preparation in 5% of patients taking soy, 3% of those taking an eHF and < 1% of those taking an AAF. Additionally, specialists started prescribing a clinical nutrition preparation for 17% of patients who were not using a formula.

Time to treatment, symptom resolution and diagnosis

It took a mean 2.2 (95% CI: 2.0; 2.3) months from initially seeing a GP before a patient received their first prescription for a first clinical nutrition preparation (). Moreover, the time to symptom resolution from the initial GP visit was a mean 2.9 (95% CI: 2.8; 3.0) months. However, this varied from 3.4 (95% CI: 3.3; 3.5) months for those initially treated with an eHF to 2.6 (95% CI: 2.5; 2.7) months for those initially treated with an AAF (). It took a mean 3.6 (95% CI: 3.4; 3.7) months from the first GP visit before a diagnosis of CMA was made (i.e. 1 month after the symptoms had resolved). Patients underwent very few blood tests or skin prick tests, suggesting that GPs were using symptom resolution as a surrogate marker for making a clinical diagnosis of CMA. GPs diagnosed CMA in 86% of cases and specialists in the remainder.

Table 6. Time to treatment, symptom resolution and diagnosis (95% confidence limits in parentheses).

Clinician visits

Patients had a mean 18.2 (95% CI: 17.5; 18.9) visits for CMA over the first 12 months from initial presentation (). However, patients who remained on their initial diet had fewer GP visits (17–19 visits) compared to those whose diet was changed (> 20 visits). Of the 42% of patients who saw a hospital clinician, 43% were paediatricians and 47% were accident and emergency clinicians. Visits to paediatric specialties and nurses made up the remainder. The mean waiting time for a referral to a paediatrician was 3.7 (95% CI: 3.5; 3.9) months. Patients had a mean 7.6 (95% CI: 7.1; 8.0) GP visits before seeing a hospital clinician ().

Healthcare cost of patient management

The 12-monthly NHS cost following initial presentation to a GP was estimated to be £1,381 (95% CI: £1,115; £1,649) per patient, although this varied according to the presenting symptoms.

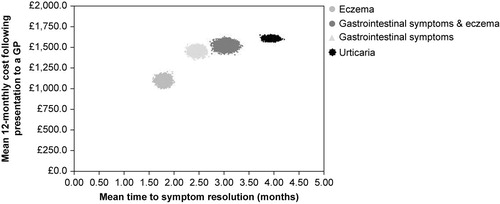

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses highlighted the differences in cost and time to symptom resolution between the different symptomatic groups ().

Figure 1. Distribution between mean costs and time to symptom resolution. (n =10,000 iterations of the model) for each symptomatic group.

GP visits were the primary cost driver, accounting for 44% of the 12-monthly cost. Clinical nutrition preparations accounted for up to a further 38% of the cost. Outpatient visits and hospital admissions accounted for a further 9% and 6%, respectively (). Additionally, 33% of the 12-monthly cost was attributable to the cost from the time of initial presentation to a GP up to the time a diagnosis of CMA was written in the patients' case notes, which was estimated to be £462 (95% CI: £424; £500). In total, 52% of this ‘diagnosis cost’ was accounted for by a mean seven GP visits per patient.

Table 7. Mean 12-monthly costs (£ at 2006/07 prices) per infant following presentation to a GP, stratified according to presenting symptoms.

Budget impact

There were 734,000 live births in the UK in 2006Citation21. By assuming the incidence of CMA to be 2.5%Citation2, it was estimated that there are 18,350 infants with new-onset CMA in the UK per annum. The NHS cost of managing 18,350 infants over the first 12 months following initial presentation to a GP was estimated to be £25.6 million and result in 336,575 (95% CI: 333,675; 339,474) visits to a GP, 12,443 (95% CI: 11,992; 12,894) outpatient visits and 1,203 (95% CI: 919; 1,483) hospital admissions. This varied according to the incidence of patients in each symptomatic group (). Notwithstanding this, the estimated ‘diagnosis cost’ for this cohort of 18,350 infants was estimated to be £8.5 million.

Table 8. Resource implications of managing 18,350 infants with new-onset CMA in the UK per annum.

Sensitivity analyses

Deterministic sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the model is relatively robust and that the only parameter that could potentially change the results is the number/frequency of GP visits and the incidence of CMA.

It was found that patients had a mean 4.2 GP visits for CMA over a period of a mean 2.2 months before they were started on a clinical nutrition preparation. Over the remaining 9.8 months of the year, patients had a mean 14.0 GP visits for CMA, which equated to one GP visit every 3 weeks. Sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the NHS cost of managing 18,350 infants over the first 12 months following initial presentation to a GP could be reduced by 26% (from £25.6 million to £19.0 million) if the frequency of GP visits was reduced from once every 3 weeks to once every 12 weeks following the start of a clinical nutrition preparation.

The study assumed the incidence of CMA to be 2.5%Citation2. However, many clinicians argue that this is an underestimate and that the incidence is more likely to be 8%. Sensitivity analysis estimated that if the incidence of CMA was 1% there would be 7,340 infants with new-onset CMA in the UK per annum costing the NHS £10.2 million over the first 12 months following initial presentation to a GP. However, if the incidence was 8%, there would be 58,720 infants with new-onset CMA in the UK per annum costing the NHS £81.9 million over the first 12 months following initial presentation to a GP.

Discussion

This is the largest study ever undertaken in CMA and is based on 1,000 patients presenting to their GP and being followed-up for 1 year. Distribution of symptoms in this large cohort of patients is different to that previously reported, as is the intolerance rates to soy and eHF. The differences may be due to previous estimates being derived from studies undertaken in secondary care involving a sub-group of patients who had been referred to specialists, smaller sample sizes (typically 20–30 patients) and shorter periods of follow-up (typically 2–3 months). Moreover, it is widely perceived by clinicians that many infants remain symptomatic with eHF. However, apart from one unpublished clinical audit which showed that 58% of infants on a whey-based eHF remained symptomatic (personal communication: Dr J Sinclair, Starship Children's Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand), there have been no studies assessing the treatment patterns of a large cohort of infants with CMA.

GPs play a far more instrumental role in the management of CMA in the UK than was previously thought. In the majority of cases, CMA was diagnosed by GPs and treatment was started by them. Moreover, 56% of infants in the data set were < 6 months of age at the start of their treatment and contrary to guidelinesCitation20, 76% of them were initially prescribed soy by their GP. Only 42% of patients saw a hospital clinician, but the diet was only changed by specialists in 8% of pre-treated patients. Additionally, specialists started prescribing a clinical nutrition preparation in 17% of referred patients who were not using a formula.

The advantages of using the THIN database is that the treatment patterns observed in this study reflect actual clinical practice. However, this naturalistic approach does have its limitations. Patients were not randomised to treatment and resource use was not collected prospectively. Nevertheless, 1,000 eligible patients have been included in the analysis, which should be a sufficiently large sample to accurately assess treatment patterns and healthcare resource use in actual clinical practice. The majority of patients were not evaluated by allergy specialists and the diagnosis of CMA may not be secure in all cases. Nevertheless, the patients have been diagnosed as having CMA by a clinician and have been managed by their GP as if they had CMA. Moreover, this is a reflection of actual clinical practice, and all patients became symptom-free during the year of follow-up after receiving a clinical nutrition preparation. Consequently, the estimates of healthcare resource use and corresponding costs in this analysis have been derived from actual cases and perceived cases of CMA. Notwithstanding this, the incidence of CMA in the THIN database is consistent with other studiesCitation2, suggesting that CMA was not over-diagnosed in this population.

CMA imposes a substantial burden on NHS resources in the UK. Many factors contribute to this burden including: the high number of GP visits (mean 18.2 visits per patient), the number of GP visits before initiating a diet (mean 4.2 visits per patient), the time taken to (1) prescribe a clinical nutrition preparation (mean 2.2 months after initially seeing a GP), (2) resolve symptoms (mean 2.9 months from the initial GP visit) and (3) make a diagnosis (mean 3.6 months from the initial GP visit). Reducing the frequency of GP visits could potentially reduce the burden of CMA on the UK's NHS.

The aim of the study was to stratify patients according to their presenting symptoms and not according to their treatment. Hence, the model only considers the cost of NHS resource use for the ‘average patient’ and no attempt has been made to stratify costs according to whether a patient received soy or a casein- or whey-based eHF formulation or an AAF. Also excluded are the costs incurred by parents and indirect costs incurred by society as a result of parents taking time off work. The analysis excluded changes in quality of life and improvements in general well-being of sufferers and their parents as well as parents' preferences. Also excluded are changes in patients' behaviour. Consequently this study may have underestimated the burden that CMA imposes on society as a whole.

The authors have also estimated the budget impact of managing CMA in FinlandCitation13, AustraliaCitation14, the Netherlands, South Africa, and the US. Based on these experiences, the authors concluded that it is difficult to generalise the findings from this study to other countries because treatment patterns for CMA vary between all six countries, including the clinicians who manage CMA sufferers, referral patterns, diagnostic procedures and prescribing patterns. For example, GPs are primarily involved in managing CMA in the UK, whereas it is a combination of GPs and youth healthcare doctors in the Netherlands, key opinion leaders at tertiary referral centres in Finland and paediatricians at secondary care centres in Australia, the US and South Africa. In the UK any physician can prescribe an AAF, whereas only a paediatrician would do so in South Africa or the Netherlands. Moreover, while clinical nutrition preparations were the key cost driver in Australia, primary care clinician visits were the primary cost driver in the UK, whereas it was tertiary care clinician visits in FinlandCitation13.

Conclusion

CMA imposes a substantial burden on the NHS. Any strategy that can improve healthcare delivery and thereby shorten the time to treatment, time to symptom resolution and time to diagnosis should potentially decrease the burden CMA imposes on the UK's NHS and release healthcare resources for alternative use within the system.

Transparency

Declaration of funding: This study was sponsored by SHS International Ltd, Liverpool, UK and Nutricia Ltd, Trowbridge, UK.

Declaration of financial/other relationships:E.S., E.N. and J.F.G. have disclosed that they are employees of Catalyst Health Economics Consultants, Northwood, UK, which received financial support from the sponsor for this study. G.L. has disclosed that he has no relevant financial relationships.

The JME peer reviewers 1 and 2 have not received an honorarium for their review work on this manuscript. Both have disclosed that they have no relevant financial relationships.

Acknowledgements: None.

References

- Hill DJ, Firer MA, Shelton MJ, Manifestations of milk allergy in infancy: clinical and immunological findings. J Pediatr 1986;109:270-276.

- Action Against Allergy. Available at http://www.actagainstallergy.co.uk.

- Høst A, Halken SA. A prospective study of cow milk allergy in Danish infants during the first 3 years of life. Clinical course in relation to clinical and immunological type of hypersensitivity reaction. Allergy 1990;45:587-596.

- Bishop J, Hill DJ, Hoskings CS. Natural history of milk allergy: clinical outcome. J Pediatr 1990;116:862-867.

- Hill DJ, Duke AM, Hosking CS, Clinical manifestations of cow's milk allergy. The diagnostic value of skin tests and RAST. Clin Allergy 1998;18:481-490.

- Walker-Smith JA. Diagnostic criteria for gastrointestinal food allergy in childhood. Clin Exp Allergy 1995;25:20-22.

- Osborn DA, Sinn J. Soy formula for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;3:CD003741.

- Seppo L, Korpela R, Lonnerdal B, A follow-up study of nutrient intake, nutritional status, and growth in infants with cow milk allergy fed either a soy formula or an extensively hydrolyzed whey formula. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:140-145.

- de Boissieu D, Matarazzo P, Dupont C. Allergy to extensively hydrolyzed cow milk proteins in infants: identification and treatment with an acid-based formula. J Pediatr 1997;131:744-747.

- Hill DJ, Heine RG, Cameron DJS, The natural history of intolerance to soy and extensively hydrolyzed formula in infants with multiple food protein intolerance (MFPI). J Pediatr 1999;135:118-121.

- Kanny G, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Flabbee J, Use of an amino-acid-based formula in the treatment of cow's milk protein allergy and multiple food allergy syndrome. Allerg Immunol 2002;34:82-84.

- Moneret-Vautrin DA, Hatahet R, Kanny G. Protein hydrolysates: hypoallergenic milks and extensively hydrolyzed formulas. Immuno-allergic basis for their use in prevention and treatment of milk allergy. Arch Pediatr 2001;8: 1348-1357.

- Guest JF, Valovirta E. Modelling the resource implications and budget impact of new reimbursement guidelines for the management of cow milk allergy in Finland. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:1167-1177.

- Guest JF, Nagy E. Modelling the resource implications and budget impact of managing cow milk allergy in Australia. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:339-349.

- The Health Improvement Network (THIN) Database. EPIC London, 2007.

- Department of Health. NHS Reference costs 2005/06. Available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/

- Netten A, Curtis L. Unit costs of health and social care 2006. University of Kent, 2006.

- Drug Tariff. Available at http://www.drugtariff.com

- British National Formulary. Available at http://www.bnf.org

- CMO's Update 37. Department of Health January 2004. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Lettersandcirculars/ CMOupdateDH_4070172.

- Office for National Statistics. Available at http://www.statistics.gov.uk/default.asp.