Abstract

Objectives:

To compare demographic and comorbidity profiles and healthcare costs of Medicaid patients with postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) treated with lidocaine patch 5% (lidocaine patch) versus patients not treated with the lidocaine patch. Repeat comparison for the subset of patients treated in long-term care (LTC) settings.

Methods:

Patients, age ≥18 years, with PHN diagnosis, or PHN-likely patients with herpes zoster diagnosis and ≥30 days of PHN-recommended treatment, were identified in Medicaid claims from Florida, Iowa, Missouri, and New Jersey (1999–2007). Patients had continuous eligibility 6 months before (baseline) and 12 months after (study period) the PHN index date. Patients with ≥1 claim for a lidocaine patch during the study period (n = 872) were compared to patients without a lidocaine patch claim (comparison group). Baseline characteristics, study period treatment and healthcare costs (reimbursements by Medicaid for medical services and prescription drugs) were compared between groups using univariate analyses.

Results:

PHN patients in the lidocaine patch group were older (64.5 vs. 62.2 years; p = 0.002) and had higher rates of pain-related comorbidities (e.g., back/neck pain, osteoarthritis) than comparison patients. Average PHN-related drug costs per patient were higher ($1994 vs. 1137; p < 0.0001) among lidocaine patch patients, with lidocaine patch accounting for $505 of the difference. PHN-related medical costs appeared lower in the lidocaine patch group, although not statistically significant ($983 vs. 1294; p = 0.1348). No significant differences were found in total healthcare costs ($20,175 vs. 19,124; p = 0.3720) across groups, despite higher total prescription drug costs among lidocaine patch patients. A similar pattern was observed among LTC patients.

Conclusions:

Despite higher rates of comorbidities and prescription drug costs, lidocaine patch patients had similar study period healthcare costs as comparison patients. The cost of the lidocaine patch represented a small fraction of overall costs incurred over the study period.

Limitations:

Findings are based on a Medicaid sample and may not be generalizable to all PHN patients.

Introduction

This is the first of two manuscripts examining Medicaid patients with postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). This paper provides a descriptive analysis of Medicaid patients with PHN, to better understand patient characteristics, and, more specifically, the characteristics of patients treated with lidocaine patch 5%, a leading topical treatment for PHN. The second paper (Kirson et al. Comparing health care costs of Medicaid patients with postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) treated with lidocaine patch 5% vs. gabapentin or pregabalin. pp. 482-491 of this issue) takes the analysis a step further, conducting an economic analysis of patients treated with lidocaine patch 5% compared with similar patients treated with oral gabapentin or pregabalin.

Background

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is a painful condition which affects approximately 10–20% of herpes zoster (HZ) patientsCitation1,Citation2. Age is a leading risk factor, with PHN almost 15 times more likely in patients over age 50Citation2,Citation3. Effective management of PHN can be complicated and costly, with total annualized costs associated with PHN estimated at $10,054 for commercially insured patients, and $17,972 for government-insured, low income, Medicaid patients (2001–2003)Citation4.

Lidocaine patch 5% (lidocaine patch) has been shown to be efficacious in treating patients with PHNCitation1,Citation5–9. However, there have been no detailed analyses of the use of lidocaine patch among Medicaid patients with PHN, or the subset of such patients in long-term care (LTC) settings. Given the age profile of PHN patients, analysis of older patient populations, including those treated in LTC settings, could be of clinical and policy relevance. Medicaid claims data include good coverage of the elderly population, including those treated in LTC, and afford the opportunity to examine more detailed cost information: (a) while the main source of health insurance for the elderly population in the US is Medicare, close to 9 million people in the US participated in both Medicare and Medicaid in 2005 (‘dual eligibles’), accounting for 46% of all Medicaid expendituresCitation10; (b) Medicaid coverage includes prescription drug benefits, which were not covered by Medicare prior to 2006, making prescription drug treatment observable in Medicaid data, but not Medicare; and (c) a substantial share of the elderly receive treatment in LTC settings, and Medicaid accounts for the largest share of LTC spending in the US (43% in 2002)Citation11.

The objective of this study was to develop a better understanding of the characteristics of Medicaid patients with PHN treated with the lidocaine patch, and examine how they differ from those patients not treated with lidocaine patch. More specifically, the study aimed to compare the demographic and comorbidity profile, treatment and healthcare (medical and prescription drug) costs of PHN Medicaid patients treated with lidocaine patch with those of Medicaid patients not treated with lidocaine patch. An additional goal was to examine the subset of PHN Medicaid patients treated in LTC settings. The analysis was conducted from the Medicaid payer perspective using observed actual utilization and Medicaid payment data. As such, it may inform payers regarding the pattern and management of costs associated with treating PHN patients.

Methods

Data source

The study sample was selected from a claims database for Medicaid beneficiaries in four states (Florida, Iowa, Missouri and New Jersey), covering approximately 10 million lives over the period 1999–2007. The database contains de-identified information on patients’ demographics (e.g., age and gender), monthly enrollment history, and medical and pharmacy claims. Utilization of medical services was recorded in the database with dates of service, associated diagnoses (up to 9 codes, depending on state, using the codes for International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, ICD-9-CM), performed procedures (Current Procedural Terminology, CPT), and actual payment amounts made to providers. The database also includes pharmacy claims with prescribed medications identified by National Drug Code (NDC), date of prescription fill, days of supply, quantity, and actual payment amounts.

Sample selection

Identification of PHN patients

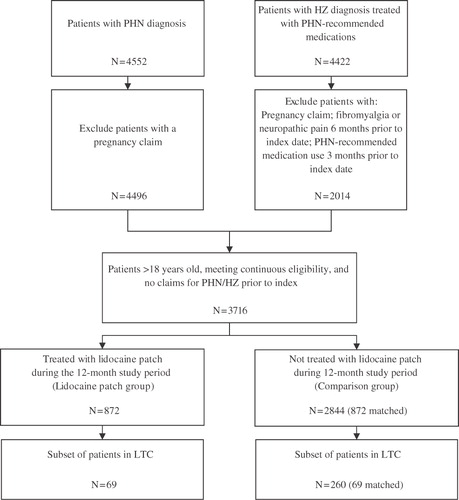

Patients were identified as having PHN if they met one of the following criteria: (1) had at least one medical claim with a PHN diagnosis (ICD-9-CM: 053.12, 053.13 or 053.19, n = 4552); or (2) had at least one medical claim with a diagnosis for HZ (ICD-9-CM: 053.0x, 053.10, 053.11, 053.2x, 053.7x, 053.8x, or 053.9x) and at least 30 days of treatment with a PHN-recommended medication beginning within 30 days of the HZ diagnosis (‘PHN-likely patients’, n = 4422). Gabapentin, pregabalin, lidocaine patch, capsaicin, duloxetine and tricyclic antidepressants were considered PHN-recommended medicationsCitation12. Given the established clinical relationship between HZ and PHNCitation13, the authors followed the existing literature and assumed that patients who had a diagnosis of HZ and were soon thereafter treated with PHN-recommended medication were, with reasonable probability, PHN patientsCitation4,Citation14. Unlike previous studies, however, only those patients who initiated treatment with PHN-recommended medication were included, rather than any form of analgesic medication. Given the nature of retrospective claims data and the clinical association between HZ and PHN, this approach balances careful sample selection and real world representativeness. It also contributes to the statistical precision of the analysis. The results of the study are qualitatively unaltered when PHN-likely patients are excluded.

As PHN treatment may be initiated within a short time following HZ diagnosis, the study index date was defined as the date of the first claim with a HZ diagnosis, with minor exceptions for which the index date was defined as the PHN diagnosis date (e.g., patients with a PHN diagnosis which precedes their HZ diagnosis). A baseline period of 6 months prior to the index date and study period of 12 months following the index date were examined. As fewer than one in 20 PHN patients still experience pain at 1 year after the HZ eruptionCitation2, a 12-month study period was deemed appropriate to capture all PHN-related utilization and costs.

Exclusion criteria, treatment groups and long-term care

To increase the likelihood that PHN-likely patients were indeed being treated for PHN, and not for other painful conditions for which the same medications may be used, they were required to have no claims for PHN-recommended medications during the 90 days prior to the index date, and no claims with diagnoses for neuropathic pain or fibromyalgia 6 months prior to the index date. Such an exclusion means that treatment was initiated only after diagnosis with PHN or HZ, and was not a direct continuation of pre-existing treatment.

In addition, patients (both PHN and PHN-likely) were excluded from the study if they: (1) were <18 years old on the index date; (2) had a pregnancy claim during baseline or study periods; or (3) did not have continuous eligibility for medical and drug benefits during the baseline and study periods.

The remaining patients (n = 3716) were separated into two mutually exclusive treatment groups, based on study-period use of lidocaine patches:

Lidocaine patch group – patients with ≥1 prescription for a lidocaine patch during the study period (n = 872);

Comparison group – patients with no claims for a lidocaine patch prescriptions during the study period (n = 2844).

Accounting for composition of PHN type

Given the descriptive nature of the study, no attempt was made to account for baseline differences across treatment groups. However, patients with neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia or PHN-recommended medication use prior to the index date were excluded from the PHN-likely cohort, but not from the cohort of patients directly identified as having PHN. Therefore, differences in the composition of PHN type (i.e., PHN vs. PHN-likely) across treatment groups could impact the baseline comparison. To ensure that differences in baseline comorbidities, treatment and resource use were not due to the sample selection criteria, lidocaine patch patients were matched to comparison group patients (1 : 1) on PHN type and type of diagnosis on index date (PHN or HZ).

The sample selection process is summarized in .

Baseline characteristics

Patient characteristics were compared between the lidocaine patch and comparison groups over the 6-month baseline period, including demographics (age, gender), baseline rates of selected comorbidities and general baseline severity measures (Charlson Comorbidity IndexCitation15,Citation16, medication use and healthcare resource utilization).

Study period resource utilization and costs

Medical services were categorized as inpatient, emergency department (ED), long-term care (LTC) or outpatient/other using a combination of provider type, provider specialty, service type, category of service, claim type and procedure code variables. The precise definitions were adjusted to match state-level differences in Medicaid coding practices. All services not categorized under LTC, inpatient, or ED were labeled as outpatient/other. PHN-related resource use and costs were identified using claims associated with an ICD–9–CM code for PHN or HZ. Prescription drug utilization was identified in the pharmacy claims using a combination of National Drug Codes, brand name and generic name. PHN-related prescription drugs included PHN-recommended medication, analgesic medications (including hydroxyzine, promethazine, anxiolytics, opioids, skeletal muscle relaxants and NSAIDs), antiviral therapy (only antivirals specific to herpes) and corticosteroids.

Average per-patient costs (overall and PHN-related) were calculated during the 12-month follow-up period. Medical costs (e.g., inpatient, emergency department, etc.) and prescription drug costs were summed separately. Total healthcare costs were calculated as the sum of medical and drug costs. Cost analyses were conducted from the Medicaid payer’s perspective (i.e., costs were defined as payments to providers by Medicaid), and do not include any adjustments for manufacturer rebates, as those are not observable in the database.

All costs were inflated to 2007 US dollars, the most recent year of available claims, using the Consumer Price Index for Medical Care.

Statistical analyses

Lidocaine patch patients were compared to comparison group patients using univariate analyses. Categorical variables (e.g., rates of comorbidities) were compared using McNemar tests for matched pairs; continuous variables (e.g., costs, Charlson Comorbidity Index) were compared using bias-corrected bootstrapping to account for their skewed distributionCitation17–19.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). p-Values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Prior to matching on PHN type, the study sample consisted of 872 lidocaine patch patients and 2844 comparison group patients, with a higher proportion of PHN-likely patients in the lidocaine patch group (38.6 vs. 31.3%; p < 0.0001). However, even after matching on PHN type, there remained significant baseline differences between lidocaine patch and comparison group patients (): lidocaine patch patients were, on average, more than 2 years older (64.5 vs. 62.2; p = 0.0024), had higher baseline use of lidocaine patch (10.1 vs. 1.3%; p < 0.0001), gabapentin (14.2 vs. 9.4%) and other analgesic medication (79.6 vs. 73.7%; p = 0.0041), and were more likely to have an ED visit (46.4 vs. 41.1%; p = 0.0242). A similar pattern was apparent among the subset of patients in LTC, though statistical precision was reduced due to small sample size.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics* of Medicaid patients with postherpetic neuralgia.

Baseline rates of comorbidities were generally higher among lidocaine patch patients, including low back pain (19.4 vs. 13.5%; p = 0.0010), other spinal and neck pain (18.6 vs. 12.0%; p = 0.0001) and osteoarthritis (11.7 vs. 8.7%; p = 0.0386). Among patients in LTC, the lidocaine patch group had higher rates of migraines/headaches (13.0 vs. 2.9%; p = 0.0348).

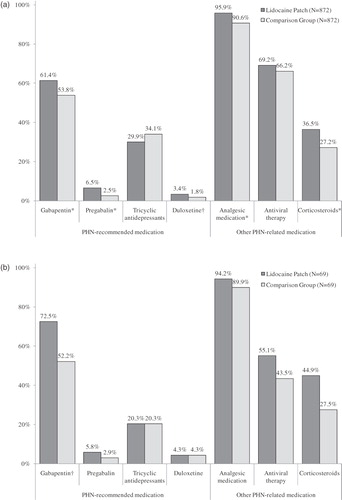

Study period treatment

During the study period 48.4% of patients in the lidocaine patch group recorded a drug claim for lidocaine patch prior to a claim for any other PHN-recommended medication. and describe study period medication use for all patients and LTC patients, respectively. Compared with patients in the comparison group, lidocaine patch patients were more likely to receive gabapentin, pregabalin, duloxetine, analgesic medication and corticosteroids during the 12-month study period. Similar patterns of results were observed for patients in LTC, though usually not statistically significant.

Figure 2. Study period treatment. (a) All Medicaid patients with postherpetic neuralgia. (b). LTC Medicaid patients with postherpetic neuralgia. *p < 0.01; †p < 0.05; significance levels based on McNemar tests for matched pairs. Medications with <1% utilization rates were omitted; analgesic medication includes: hydroxyzine, promethazine, anxiolytics, opioids (including tramadol), skeletal muscle relaxants and NSAIDs (including combinations, indomethacin and COX-2 inhibitors); antiviral therapy includes only antivirals specific to herpes.

Study period healthcare resource utilization and costs

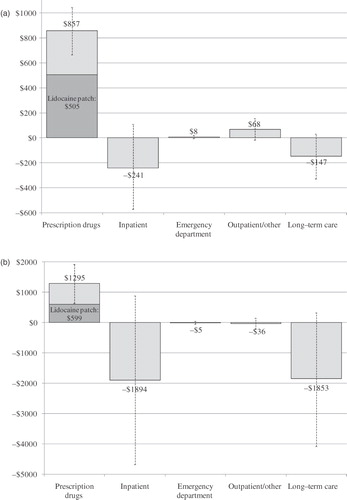

reports healthcare resource utilization during the 12-month study period, both overall and PHN-related. Costs are reported in . On average, total direct costs were $20,175 among lidocaine patch patients, compared with $19,124 for comparison group patients (difference: $1051; p = 0.372). Total prescription drug costs were higher among lidocaine patch patients ($7658 vs. 6198; difference: $1461; p < 0.0001), consistent with higher rates of prescription drug use found in . However, total medical costs appeared to be nominally lower in the lidocaine patch group ($12,516 vs. 12,926; difference: −$410; p = 0.7077).

Table 2. Study period healthcare resource utilization.

Table 3. Mean per-patient study period healthcare costs.

Differences in mean PHN-related costs are reported in (all patients) and 3b (LTC). PHN-related drug costs were $857 higher in the lidocaine patch group ($1994 vs. 1137; p < 0.0001), of which $505 are attributable directly to the cost of the lidocaine patch. However, total PHN-related healthcare costs were only $546 higher ($2977 vs. 2431; p = 0.0188). PHN-related medical costs appeared lower in the lidocaine patch group, though not statistically significant ($983 vs. 1294; p = 0.1348). Overall, PHN-related costs accounted for just under 15% of total healthcare costs. In the lidocaine patch group, lidocaine patch costs represented 2.5% of total healthcare costs ($20,175) during the study period.

Figure 3. Differences in mean PHN-related costs. (a) All Medicaid patients with PHN. (b) LTC Medicaid patients with PHN. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals; costs were compared using bias-corrected bootstrapping. PHN-related costs were calculated over the 12-month study period and inflated to 2007 US dollars using the CPI for medical care. Differences in mean costs were defined as mean per-patient costs in the lidocaine patch group minus mean per-patient costs in the comparison group.

At a per-patient cost of over $52,000 during the 12-month study period, the economic burden associated with LTC patients was approximately 2.5 times higher than the average for all patients. Again, while total prescription drug costs were higher among lidocaine patch patients ($8660 vs. 5790; p = 0.0355), there was no significant difference across treatment groups in total direct costs ($52,244 vs. 52,473; p = 0.9808). PHN-related medical costs were $3787 lower in the lidocaine patch group ($1526 vs. 5313; p = 0.0353), more than offsetting higher PHN-related prescription drug costs ($2276 vs. 981; p = 0.0002). Total PHN-related costs were $2492 lower among LTC lidocaine patch patients ($3802 vs. 6294; p = 0.1615).

Discussion

Multiple studies have established the substantial costs associated with HZ and PHN, including direct costs due to prescription medication and medical resource utilization, indirect costs associated with work-loss and disability, and reduced quality of life due to debilitating painCitation4,Citation14,Citation20–22. While retrospective analyses of claims data have been used to estimate the costs associated with PHN patients, including the US Medicaid populationCitation4,Citation14, no study, to the authors’ knowledge, has examined the economic profile of PHN Medicaid patients treated with lidocaine patch 5%. Moreover, no study has examined the subset of PHN patients treated in LTC settings, a group which is of considerable relevance given the demographic profile of PHN patients.

To better describe PHN Medicaid patients treated with the lidocaine patch, this study has contrasted them with PHN Medicaid patients not treated with the lidocaine patch. As such, the study design compared PHN patients potentially treated with the full universe of PHN treatments (lidocaine patch group) with PHN patients not receiving lidocaine patch (comparison group). One would expect the lidocaine patch group, as constructed, to include more severe patients, on average, either in terms of PHN severity, or in terms of associated comorbidities. Therefore, it is not surprising that lidocaine patch patients were older and had higher baseline rates of comorbidities and medication use. Note, however, that PHN severity was not directly observable in the data. As the goal of the study was not to ascertain the economic value of one treatment or another, but, rather, to describe the PHN patients treated with lidocaine patch, no attempt was made to control for underlying differences between treatment groups. Therefore, the reported results should be viewed as descriptive, and caution should be used in their interpretation. Matching on PHN type and index date diagnosis was used to eliminate possible bias introduced by the sample selection process, not to account for clinical baseline differences.

A high degree of concomitant medication use during the study period was observed among PHN patients in both treatment groups. This pattern likely understates concomitant drug utilization, however, as over the counter medication use (and associated out-of-pocket costs) were not captured in the database. Consistent with higher rates of baseline comorbidities and treatment, patients in the lidocaine patch group were more likely to receive gabapentin, pregabalin, duloxetine and analgesic medication during the 12-month study period ( and ).

By construction, PHN patients in the comparison group were not treated with lidocaine patch 5%, contributing to significantly higher prescription drug costs in the lidocaine patch group. However, the costs associated with lidocaine patch treatment accounted for only a small fraction of the overall costs incurred by PHN patients in the lidocaine patch group. Moreover, despite higher rates of baseline comorbidities and higher study period drug costs than comparison-group patients, lidocaine patch patients had similar total healthcare costs. While not statistically significant, the point estimates for total medical costs and for PHN-related medical costs appeared lower in the lidocaine patch group. As this study is descriptive, further research is necessary to determine whether treatment with lidocaine patch is statistically associated with medical cost savings. A similar pattern was observed among LTC patients, with higher overall drug costs coupled with seemingly lower overall medical costs. For PHN-related costs, however, the difference was both substantively and statistically significant, with LTC lidocaine patch patients incurring $3787 (p = 0.0353) less in PHN-related medical costs over the 12-month study period, more than offsetting higher PHN/HZ-related drug costs.

At a per-patient cost of approximately $20,000 over a 12-month period, total healthcare costs estimated for PHN Medicaid patients in this study are consistent with results previously reported among the Medicaid populationCitation4,Citation14. Previous studies, however, did not estimate resource utilization and costs specifically for PHN patients treated with lidocaine patch, nor for the subset of patients treated in LTC setting.

The study findings should be interpreted in the context of the study sample selection criteria. The study sample was drawn from a pool of Medicaid beneficiaries in four states. While multiple published studies have made use of these and similar Medicaid claims dataCitation23–27, the findings for this sample may not be generalizable to the overall population of patients with PHN. In addition, utilization and costs captured in the study only reflect Medicaid claims, and do not capture Medicare claims for dual eligible patients. With approximately 50% of the study sample aged 65 and up, it is possible that per-patient costs are underestimated in this study. As lidocaine patients were approximately 2 years older, on average, cost underestimation may vary somewhat across treatment groups.

Conclusion

Despite higher rates of comorbidities and prescription drug costs, lidocaine patch patients had similar study period healthcare costs as comparison group patients. The cost of lidocaine patch represented a small fraction of overall costs incurred over the study period.

PHN is an extremely painful condition which affects a significant share of HZ patients. Healthcare resource use and costs associated with treating PHN patients are substantial, especially among patients treated in LTC settings. Improved disease management and treatment of PHN may lead to possible savings. This study presents suggestive evidence that treatment with lidocaine patch may be associated with medical cost savings, but further research is necessary to substantiate that finding.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Endo Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

N.Y.K., H.G.B., R.W., E.K., and J.I.I. have disclosed that they are employees of Analysis Group, a company under contract with Endo Pharmaceuticals to conduct this study. R.A.P., R.H.B-J., and K.H.S. have disclosed that they are employees of Endo Pharmaceuticals.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Stephen Camper of Endo Pharmaceuticals, Inc. for his assistance in manuscript preparation and review.

Material from this study was presented as a poster at the American Pain Society’s 29th annual scientific meeting, Baltimore, MD, May 6–8, 2010, under the title: ‘Descriptive profile of Medicaid patients with postherpetic neuralgia treated and untreated with lidocaine patch 5%’.

References

- Dubinsky RM, Kabbani H, El-Chami Z, et al. Practice parameter: treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: an evidence-based report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2004;63:959-965

- Stankus SJ, Dlugopolski M, Packer D. Management of herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Am Fam Physician 2000;61:2437-2444, 2447-2448

- Kost RG, Straus SE. Postherpetic neuralgia – pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. N Engl J Med 1996;335:32-42

- Dworkin RH, White R, O’Connor AB, et al. Health care expenditure burden of persisting herpes zoster pain. Pain Med 2008;9:348-353

- Rowbotham MC, Davies PS, Verkempinck C, et al. Lidocaine patch: double-blind controlled study of a new treatment method for post-herpetic neuralgia. Pain 1996;65:39-44

- Galer BS, Rowbotham MC, Perander J, et al. Topical lidocaine patch relieves postherpetic neuralgia more effectively than a vehicle topical patch: results of an enriched enrollment study. Pain 1999;80:533-538

- Galer BS, Jensen MP, Ma T, et al. The lidocaine patch 5% effectively treats all neuropathic pain qualities: results of a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, 3-week efficacy study with use of the neuropathic pain scale. Clin J Pain 2002;18:297-301

- Dworkin RH, Schmader KE. Treatment and prevention of postherpetic neuralgia. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:877-882. Epub 2003, Mar 13. Review

- Dworkin RH, Backonja M, Rowbotham MC, et al. Advances in neuropathic pain: diagnosis, mechanisms, and treatment recommendations. Arch Neurol 2003;60:1524-1534. Review

- Holahan J, Miller DM, Rousseau D. Dual eligibles: Medicaid enrollment and spending for Medicare beneficiaries in 2005. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Issue Brief, February 2009

- O’Brian E, Elias R. Medicaid and long-term care. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, May 2004

- Tyring S. Management of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;57:s136-142

- Gnann JW, Whitley RJ. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med 2002;347:340-346

- Dworkin RH, White R, O’Connor AB, et al. Healthcare costs of acute and chronic pain associated with a diagnosis of herpes zoster. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1168-1175

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-383

- Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis J. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1075-1079

- Rascati KL, Smith MJ, Neilands T. Dealing with skewed data: an example using asthma-related costs of Medicaid clients. Clin Ther 2001;23:481-498

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall, 1993

- SAS Institute. Jackknife and Bootstrap Analyses. http://support.sas.com/kb/24/982.html

- Gauthier A, Breuer J, Carrington D, et al. Epidemiology and cost of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in the United Kingdom. Epidemiol Infect 2009;137:38-47. Epub 2008, May 9

- Rothberg MB, Virapongse A, Smith KJ. Cost-effectiveness of a vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:1280-1288

- Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2008;57:1-30

- Faught E, Duh MS, Weiner JR, et al. Nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs and increased mortality: findings from the RANSOM Study. Neurology 2008;71:1572-1578. Epub 2008, Jun 18

- Faught RE, Weiner JR, Guérin A, et al. Impact of nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs on health care utilization and costs: findings from the RANSOM study. Epilepsia 2009;50:501-509. Epub 2008, Oct 3

- Wu EQ, Shi L, Birnbaum H, et al. Annual prevalence of diagnosed schizophrenia in the USA: a claims data analysis approach. Psychol Med 2006;36:1535-1540. Epub 2006, Aug 15

- Yu AP, Ben-Hamadi R, Birnbaum HG, et al. Comparing the treatment patterns of patients with schizophrenia treated with olanzapine and quetiapine i the Pennsylvania Medicaid population. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:755-764

- Yu AP, Atanasov P, Ben-Hamadi R, et al. Resource utilization and costs of schizophrenia patients treated with olanzapine versus quetiapine in a Medicaid population. Value Health 2009;12:708-715