Abstract

Objective:

To compare the demographics, clinical characteristics and resource utilization of patients with bipolar disorder who required frequent psychiatric interventions (FPIs) with those needing fewer interventions in the Duke Healthcare System database between 1999 and 2005.

Methods:

This retrospective analysis was conducted using electronic medical records of bipolar patients with FPIs, defined as having ≥4 clinically significant events (CSEs) in any 12-month period while in the Duke University Healthcare System. CSEs were composed of emergency room visits, inpatient hospitalizations, or a change in psychotropic medication due to psychiatric symptoms (score ≥4 on the Clinical Global Impressions–Severity scale). Data were compared between patients with and without FPIs.

Results:

Of 632 patients with bipolar disorder 52.5% were identified as having FPIs. These patients were younger and more often female and African American than those with fewer interventions (p < 0.01 for all). Patients with FPIs were generally prescribed more psychotropic and non-psychotropic medications, utilized more healthcare resources and experienced more psychiatric co-morbidities than those who did not require FPIs (p < 0.01 for all).

Limitations:

These results are from a single healthcare system and may not be generalizable to all patients with bipolar disorder. This analysis was retrospective and relied on availability of adequate information recording and coding of diagnoses by physicians.

Conclusions:

Patients with bipolar disorder who required FPIs were significantly different from those with fewer clinically defined interventions with respect to their demographic and clinical characteristics and prescribed medications.

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a serious chronic mental illness characterized by lifelong periodic mood episodes separated by periods of relative wellnessCitation1, with a 12-month incidence in the United States estimated between 1.3% and 2.0%Citation2–4. Patients with bipolar disorder also represent a significant economic burden, estimated at $7 billion in direct medical costs and $38 billion in indirect costs in the United StatesCitation5. In addition, comparisons of resource utilization between patients with bipolar disorder and age- and gender-matched patients who do not have bipolar disorder found that those with bipolar disorder used three to four times more healthcare resources, incurred four times greater costs per patient, incurred higher drug costs and required more frequent psychiatric hospitalizations, outpatient visits and emergency room (ER) visitsCitation6–8.

In patients with bipolar disorder, the extent of healthcare resource use and overall treatment costs are expected to vary depending on the severity of illness. Indeed, those with a more insidious disease course may require frequent interventions. For purposes of this analysis, frequent psychiatric intervention (FPI) was defined as four or more interventions in the previous year to address mood symptoms and was used as a surrogate marker for severity.

Various outcome measures in bipolar patients whose illness reached this stage were analyzed using the Clinical Management Research Information System (CRIS), a large clinical database developed by the Duke University Medical Center Department of PsychiatryCitation9. To assess differences in demographics, clinical characteristics and resources used, electronic medical records data were compared between patients whose conditions fit the FPI definition and those whose conditions did not.

Patients and methods

Study design and data source

This retrospective analysis evaluated data obtained from electronic medical records for all patients examined during visits to the Department of Psychiatry at Duke University Medical Center from 1999 to 2005. The catchment area is the Piedmont region of North Carolina, with 75% of the patients living within 100 miles of Duke University. Individual patient information (demographics, diagnoses, medications, hospitalizations, ER visits and clinical rating scales) is collected and stored in this repository in a longitudinal, anonymous manner that complies with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The data tables from CRIS were retrospectively reviewed by the authors, enabling a large-scale, naturalistic examination of patients with and without FPIs.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible patients were in the system for 1 or more years, had a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), diagnosis for bipolar disorder (type I or II) and received treatment from a physician. FPI terminology was derived from the DSM-IV-TR definition of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder, characterized as four or more mood episodes a yearCitation10. Compared with patients with bipolar disorder who experienced fewer annual mood episodes, this patient population was generally considered more difficult to treat, with higher morbidityCitation11,Citation12.

For this analysis, patients with FPIs experienced four or more clinically significant events (CSEs) requiring intervention in any 12-month period recorded in CRIS. A CSE was defined as an ER visit related to bipolar disorder, inpatient psychiatric hospitalization or a change in psychotropic medication associated with psychiatric symptoms (i.e., score ≥4 on the Clinical Global Impressions–Severity [CGI-S] scale). All CSEs were at least 7 days apart, and hospitalizations defined as CSEs were for separate episodes rather than successive hospitalizations for a single episode.

Study measures and statistical analysis

Patient demographics were recorded at study entry into the database, and all psychiatric and medical diagnoses were recorded for each visit. In addition, psychiatric and substance abuse co-morbidities and healthcare resource use (ER visits, hospitalization, outpatient visits and psychiatric and non-psychiatric medications) were recorded. In analyses comparing resource use and costs, only those attributable to bipolar disorder were considered. Daily inpatient physician assessments were equated with an inpatient length of stay (i.e., hospital days). All pertinent patient data were entered in the database. Resource use and costs were annualized and presented on a per-patient per-year basis.

Suicidality was determined by documenting suicidal thoughts, intent or behaviors (e.g., overdose, self-injurious behavior) based on the Mental Status Examination and information from the patient’s psychiatric history and the physician’s clinical notes. CGI-S scores were rated by the treating physician at each visit, and baseline severity measures were determined at the time of the initial psychiatric visit.

Between-group differences for continuous variables were analyzed using an analysis of variance model; categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. All descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were calculated using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

After examination of the full complement of study variables, a final set of the most commonly referenced variables in the database was evaluated using multivariate logistic regression models to assess their relationship with frequent interventions. The importance of each covariate for predicting this probability was measured by the magnitude of the parameter coefficient (odds ratio). The following variables were used: age (≥40 vs. <40), African American race (yes vs. no), female gender (yes vs. no), depressive disorders (yes vs. no), anxiety disorders (yes vs. no), personality disorders (yes vs. no), relationship problems (yes vs. no), substance abuse (yes vs. no), baseline CGI-S severity (≥5 vs. <5) and suicidality (yes vs. no). Statistical significance of the multivariate models was evaluated using the chi-square test. No adjustments were made for multiplicity.

A published study by Stensland et al. (2007)Citation13 provided 2004 unit costs of resources associated with bipolar disorder. Their analysis used data from the PharMetrics Integrated Outcomes Database of adjudicated medical and pharmaceutical claims for more than 6 million patients from six United States health plans. Costs of resources were inflated to 2008 unit costs using Bureau of Labor Statistics Medical Care ServicesCitation14 and Prescription Drugs Inflation RatesCitation15. The unit costs of resources are shown in . Costs for resource utilization and medications were calculated by multiplying the values for each group by the adjusted 2008 costs. No inferential statistics were computed for the cost variables.

Table 1. 2008 unit costs of psychiatric resources.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics

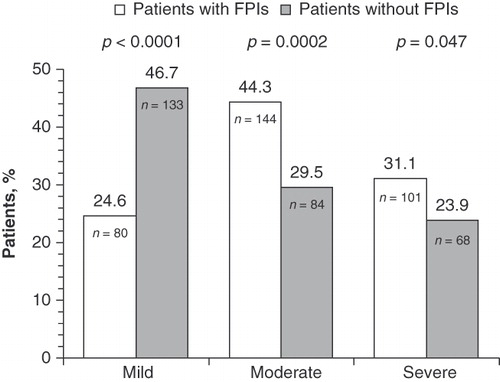

A total of 632 patients met the inclusion criteria (). The majority of the population was female (60.4%) and Caucasian (68.4%), with a mean age of 40.5 years. Of the 632 patients with bipolar disorder, 332 (52.5%) met the criteria for FPIs. The median time between CSEs for these patients was 49 (range, 7–317) days. Patients differed in their demographics and clinical characteristics based on the number of interventions required (). Those who required FPIs were younger (39.1 vs. 42.2 years; p = 0.0015) and more likely to be female (66.3% vs. 54.0%; p = 0.0016) and African American (24.5% vs. 15.4%; p = 0.0045) than patients who did not. CGI-S ratings in patients with FPIs confirmed that they had more severe illness than those without FPIs upon entry into this health system (), with a higher percentage rated as having moderate illness (44.3% vs. 29.5%; p = 0.0002) or severe illness (31.1% vs. 23.9%; p = 0.047). Moreover, a significantly higher proportion of patients who required FPIs were classified as suicidal at some point during their recorded treatment compared with those who did not (n = 208 [62.7%] vs. n = 90 [30.0%]; p < 0.0001) ().

Figure 1. Baseline CGI-S ratings at first visit for patients who required FPIs vs. those who did not require FPIs. CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions–Severity; FPIs, frequent psychiatric interventions. N = 610 (FPIs, n = 325; no FPIs, n = 285).

Table 2. Comparison of baseline demographics, medication use and suicidality in patients with or without FPIs.

Patients with FPIs also used more psychiatric resources than those without FPIs, including mean ER visits per patient (2.2 vs. 0.5 visits; p = 0.0001), mean hospitalization days (5.5 vs. 1.7 days; p = 0.0001) and mean outpatient visits per patient (24.4 vs. 11.0 visits; p = 0.0001) (). As expected, patients with FPIs were prescribed a significantly higher mean number of psychotropic (2.9 vs. 2.3; p < 0.0001) and non-psychotropic (2.5 vs. 1.9; p = 0.0025) medications per psychiatric visit. Specific medication classes prescribed were statistically different between patients with or without FPIs and are summarized in .

Table 3. Concomitant medications with statistically significant use in patients with or without FPIs*.

Co-morbidities

Patients with FPIs had a significantly higher percentage of psychiatric co-morbidities than those with fewer interventions (). The most common psychiatric co-morbidities that were more prevalent in patients with FPIs were anxiety disorders (40.4% vs. 25.7%; p < 0.0001), depressive disorders (38.6% vs. 23.7%; p < 0.0001) and personality disorders (31.9% vs. 10.0%; p < 0.0001). In addition, a significantly higher proportion of patients in this subgroup were diagnosed with a substance abuse or dependence disorder (39.8% vs. 28.0%; p = 0.0019). In patients needing FPIs compared with those needing fewer interventions, the most common substance abuse disorders were related to alcohol (24.4% vs. 17.7%; p = 0.0387) and cocaine (18.1% vs. 10.3%; p = 0.0057) ().

Table 4. Psychiatric and substance abuse co-morbidities that were statistically significant in patients with and without FPIs*.

Cost analysis

Mean direct 12-month psychiatric per-patient costs for patients with FPIs were more than double those for patients with fewer interventions ($11,414 vs. $4790, respectively) (). The largest percentage of total direct psychiatric costs was attributable to inpatient hospitalizations in patients with FPIs (43.7% of total direct costs). Psychiatric medication costs were the second-largest cost component (26.1%), followed by psychiatric outpatient visits (18.2%) and psychiatric ER visit costs (12.0%). In patients with fewer interventions, psychiatric medication costs were the largest cost component (42.8%), followed by inpatient psychiatric hospitalization (31.4%), psychiatric outpatient visits (19.6%) and psychiatric ER visits (6.2%). For psychiatric medication costs, antipsychotics were the highest cost driver in patients with FPIs compared with patients without FPIs ($1165 vs. $626), followed by anticonvulsants ($1081 vs. $850).

Table 5. Annual per-patient direct psychiatric medical and pharmacy costs in patients with and without FPIs.

Predictors of frequent psychiatric interventions

Multivariate logistic analysis demonstrated that several patient characteristics were associated with FPIs (). When only demographics were included in the model, females were 1.595 times more likely to require interventions than males (p = 0.005) and African Americans were 1.564 times more likely to require FPIs than non-African Americans (p = 0.033). However, when all factors were included in the model, gender and race were not statistically significant. Patients with a personality disorder and those with relationship problems were 2.675 (p < 0.0001) and 2.818 (p = 0.0034) times more likely to require FPIs, respectively. Patients exhibiting a high degree of suicidality were 2.561 (p < 0.0001) times more likely to require FPIs than those without demonstrated suicidal tendencies.

Table 6. Variables associated with FPIs (multivariate analysis).

Discussion

This study evaluated a patient population with bipolar disorder and clinically defined FPIs. As described previously, FPIs were used as a surrogate for disease severity. Given the nosological limitations of ‘rapid-cycling’ as a course descriptor for bipolar disorderCitation16–18, a bipolar patient population with functionally defined FPIs was studied. Compared with rapid-cycling patients, patients in the current study did not necessarily meet all the specified criteria for ‘rapid-cycling’. Approximately 50% of the total bipolar population evaluated in this retrospective review were classified as requiring FPIs.

The results of this study suggest bipolar patients requiring FPIs can be distinguished by several important characteristics. In this database, patients with FPIs were more likely to be younger, to be African American and to be female. Their disease was more severe as measured by baseline CGI-S ratings, use of psychotropic and non-psychotropic medications, psychiatric co-morbidities and concurrent substance abuse. In addition, patients with FPIs exhibited more suicidal thinking and behavior than patients without FPIs. Additionally, the multivariate analysis suggests that suicidality, relationship problems and personality disorders are also significantly associated with FPIs. Although race and gender were initially significant predictors of FPIs, they were not significant predictors when co-morbidities, baseline CGI-S and suicidality were included in the multivariate model.

Based on substantial evidence that bipolar disorder is associated with significant impairment to functioning and well-beingCitation19, healthcare resource use and cost were examined. A better understanding of these variables in patients with bipolar disorder may be helpful for healthcare payers and others interested in disease management and cost containment. Cost-based estimates of the disease burden are useful because the unit of analysis is comparable across different illnesses and the cost estimates are comprehensive.

The resource use observed in this analysis indicates the number of days of acute bipolar illness and the extent of the associated disability, particularly in patients requiring FPIs. On average, within a 12-month time frame, this subgroup experienced approximately 2.2 ER visits, 5.5 days of hospitalization and more than 24 outpatient visits. The direct per-patient 12-month healthcare cost for bipolar patients with FPIs was in excess of $11,000 – more than twice the cost for patients without FPIs. The average per-patient cost observed in this analysis is similar to that found in previous cost studies of bipolar disorderCitation8,Citation13,Citation20,Citation21. The majority of total direct costs for patients with bipolar disorder requiring FPIs resulted from inpatient hospitalization.

Several limitations of this work should be noted. First, these results are from a single healthcare system and therefore may not be generalizable to all patients with bipolar disorder. Differences in healthcare plans and patient characteristics must be considered before attempting to extrapolate these findings to other settings and patient populations. Furthermore, this analysis was retrospective and relied on adequate information recording and coding of diagnoses subject to physician judgment. As a consequence, results reported here represent an approximation of both disease classification and disease burden. Finally, any resource utilization outside the Duke system was not captured in this analysis. However, most patients received the majority of their healthcare services within the Duke system.

Cost data from the PharMetrics database may not reflect the cost of patients who have no private health insurance, and socio-economic status was not considered for this analysis. Additionally, costs for psychiatric co-morbidities were assessed at the final visit. Costs for co-morbid medical conditions were not readily available, so this comparison and comparisons of total healthcare costs (including all co-morbidities) could not be made.

This was the authors’ most homogenous and recent source of cost data. Identification of cost data for bipolar disorder is difficult because psychiatric care is not included in many available databases. However, this database contains information across more than 30,000 de-identified patients who have experienced more than 200,000 qualified clinical visits. As such, it provides a naturalistic, ‘real world’ insight into characteristics of persons with bipolar disorder who require FPIs. Additionally, patient visits are tracked over time, enabling large-scale, naturalistic examination of patient progress over long periods. A future goal is to continue to build a model using a longitudinal psychiatric database to identify a bipolar patient profile. Clinicians may use this profile for their patients with bipolar disorder to avoid FPIs.

Conclusion

Patients with bipolar disorder who were identified in this analysis as requiring FPIs were significantly different from those requiring fewer interventions on assessments of demographic and clinical characteristics, psychiatric co-morbidities, resource utilization and medication type. These data suggest patients with bipolar disorder with FPIs have distinguishing characteristics and require significant psychiatric intervention. The work described here may facilitate the prospective identification of this particular subpopulation, and cost–benefit analyses can be conducted to improve patient outcomes and reduce overall healthcare costs.

Transparency

Declaration of funding:

This analysis was supported by funding from Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, Titusville, NJ, USA. Duke University Behavioral Health Informatics was contracted by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Services, LLC, to access and analyze the data provided in this manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships:

J.T.H. is a full-time employee of Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development, LLC, and a Johnson & Johnson stockholder. N.T., C.C., R.D. and L.A. have disclosed that they are full-time employees of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and Johnson & Johnson stockholders. W.M. has disclosed that at the time of this analysis he was a full-time employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. B.B. and K.G. have disclosed that they have no conflicts of interest to report.

Acknowledgments:

The authors wish to acknowledge the writing and editing assistance provided by Matthew Grzywacz, PhD, and ApotheCom (funding supported by Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC) in the development and submission of this manuscript. The authors also wish to acknowledge Earle Bain, MD, for his significant contributions to the early stages of this work. Dr Bain is a former employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and is currently an employee of Abbott Laboratories, Inc.

The study data have been presented at the following congresses:

Society of Biological Psychiatry Annual Meeting, May 17–19, 2007, San Diego, CA; International Conference on Bipolar Disorder, June 7–9, 2007, Pittsburgh, PA; US Psychiatry and Mental Health Congress Annual Meeting, October 11–14, 2007, Orlando, FL; Institute on Psychiatric Services Annual Meeting, October 2--5, 2008, Chicago, IL, USA.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry 2002;159(4Suppl):1-50

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994;51:8-19

- Kessler RC, Rubinow DR, Holmes C, et al. The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar I disorder in a general population survey. Psychol Med 1997;27:1079-1089

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:1205-1215

- Wyatt RJ, Henter I. An economic evaluation of manic-depressive illness—1991. Soc Psych Psychiatric Epidemiol 1995;30:213-219

- Bryant-Comstock L, Stender M, Devercelli G. Health care utilisation and costs among privately insured patients with bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord 2002;4:398-405

- Stender M, Bryant-Comstock L, Phillips S. Medical resource use among patients treated for bipolar disorder: a retrospective, cross-sectional, descriptive analysis. Clin Ther 2002;24:1668-1676

- Gardner HH, Kleinman NL, Brook RA, et al. The economic impact of bipolar disorder in an employed population from an employer perspective. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1209-1218

- Gersing K, Krishnan R. Clinical computing: Clinical Management Research Information System (CRIS). Psychiatr Serv 2003;54:1199-1200

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. Text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000:427-428

- Coryell W, Endicott J, Keller M. Rapidly cycling affective disorder: demographics, diagnosis, family history, and course. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:126-131

- Kupka RW, Luckenbaugh DA, Post RM, et al. Comparison of rapid-cycling and non-rapid-cycling bipolar disorder based on prospective mood ratings in 539 outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1273-1280

- Stensland MD, Jacobson JG, Nyhuis A. Service utilisation and associated direct costs for bipolar disorder in 2004: an analysis in managed care. J Affect Dis 2007;101:187-193

- United States Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Databases. Consumer Price Index—Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers: Medical Care Services. http://data.bls.gov/PDQ/servlet/SurveyOutputServlet?years_option=all_years&output_view=data&periods_option=all_periods&output_format=text&reformat=true&request_action=get_data&initial_request=false&data_tool=surveymost&output_type=column&series_id=CWUR0000SAM2. Last accessed November 2009

- United States Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Databases. Consumer Price Index—Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers: Prescription drugs. http://data.bls.gov/PDQ/servlet/SurveyOutputServlet?years_option=all_years&output_view=data&periods_option=all_periods&output_format=text&reformat=true&request_action=get_data&initial_request=false&data_tool=surveymost&output_type=column&series_id=CWUR0000SEMA. Last accessed November 2009

- Coryell W, Solomon D, Turvey C, et al. The-long term course of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:914-920

- Koukopoulos A, Sani G, Koukopoulos AE, et al. Duration and stability of the rapid-cycling course: a long-term personal follow-up of 109 patients. J Affect Disord 2003;73:75-85

- Maj M, Pirozzi R, Formicola AM, et al. Reliability and validity of four alternative definitions of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1421-1424

- Revicki DA, Matza LS, Flood E, et al. Bipolar disorder and health-related quality of life: review of burden of disease and clinical trials. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23:583-594

- Guo JJ, Keck PE Jr, Li H, et al. Treatment costs and health care utilisation for patients with bipolar disorder in a large managed care population. Value Health 2008;11:416-423

- Eaddy M, Grogg A, Locklear J. Assessment of compliance with antipsychotic treatment and resource utilisation in a Medicaid population. Clin Ther 2005;27:263-272