Abstract

Objective:

Treatment in the hospital setting accounts for the largest portion of healthcare costs for COPD, but there is little information about components of hospital care that contribute most to these costs. The authors determined the costs and characteristics of COPD-related hospital-based healthcare in a Medicare population.

Methods

Using administrative data from 602 hospitals, 2008 costs of COPD-related care among Medicare beneficiaries age ≥65 years were calculated for emergency department (ED) visits, simple inpatient admissions and complex admissions (categorized as intubation/no intensive care, intensive care/no intubation, and intensive care/intubation) in a cross-sectional study. Rates of death at discharge and trends in costs, length of stay and readmission rates from 2005 to 2008 also were examined.

Main results:

There were 45,421 eligible healthcare encounters in 2008. Mean costs were $679 (SD, $399) for ED visits (n = 10,322), $7,544 ($8,049) for simple inpatient admissions (n = 25,560), and $21,098 ($46,160) for complex admissions (n = 2,441). Intensive care/intubation admissions (n = 460) had the highest costs ($45,607, SD $94,794) and greatest length of stay (16.3 days, SD 13.7); intubation/no ICU admissions had the highest inpatient mortality (42.1%). In 2008, 15.4% of patients with a COPD-related ED visit had a repeat ED visit and 15.5–16.5% of those with a COPD-related admission had a readmission within 60 days. From 2005 to 2008, costs of admissions involving intubation increased 10.4–23.5%. Study limitations include the absence of objective clinical data, including spirometry and smoking history, to validate administrative data and permit identification of disease severity.

Conclusions:

In this Medicare population, COPD exacerbations and related inpatient and emergency department care represented a substantial cost burden. Admissions involving intubation were associated with the highest costs, lengths of stay and inpatient mortality. This population needs to be managed and treated adequately in order to prevent these severe events.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive disease characterized by airway inflammation, mucociliary dysfunction and air flow obstruction that is not entirely reversibleCitation1–3. The disease requires careful treatment and interdisciplinary management in older patients. As it progresses, substantial limitations in cognitive, social and physical activities occurCitation4. Because COPD is a systemic disease, it has extrapulmonary effects, and elderly individuals with COPD are at increased risk for cardiovascular events, depression, osteoporosis and other significant comorbiditiesCitation5.

Based on national data, it is estimated that 23.7% of US adults age 65 years and older have COPDCitation6. However, a study of Medicare managed-care plan enrollees with healthcare claims in 2004 found that 34.6% of those age 65–74 years and 48.6% of those age 75–84 years had the disease, indicating the disease represents a substantial burden to the Medicare systemCitation7. Various studies of insured populations have found COPD patients have healthcare costs that are 1.4–2.4 times higher than those of patients without the diseaseCitation7–9 and hospital care accounts for 52–70% of direct medical costsCitation3,Citation10–14. This is not surprising, since individuals with COPD experience one to three exacerbations a year and severe episodes often require inpatient treatmentCitation15,Citation16. Nationally, the rate of hospitalization for COPD in persons age 65 years and older is 11.5 per 1,000, nearly four times the rate seen for asthmaCitation17. In the study of Medicare managed-care enrollees, 56% of those with COPD were hospitalized for any reason during the year compared to only 14% of enrollees without COPD, and emergency room visits occurred 2.3 times more oftenCitation7.

Although hospitalization is the most important cost driver of healthcare costs for COPD, little is known about the components of care that most drive costs. The primary aims of this study were to describe the direct healthcare costs of COPD among Medicare beneficiaries treated in the hospital setting, including emergency department (ED) and inpatient care, and to characterize inpatient costs by type of admission. Actual hospital costs were used, rather than billed charges, in order to depict costs from the hospital perspective.

Methods

This retrospective, cross-sectional, observational study of healthcare costs and utilization was conducted using administrative data from the Premier Perspective Database (Premier, Inc., Charlotte, NC, USA). The database contains de-identified data from 602 acute care hospitals in the US, including hospital and patient demographic characteristics, diagnosis and procedure codes, costs, and drugs dispensed. The database contains both billed charges and costs; in this analysis, cost data were used in order to most accurately reflect actual hospital costs. Because actual costs can be more or less than billed charges, they provide a very useful perspective to hospital administrators and clinical audiences. Costs in the Premier database are determined at the local level. Approximately three-quarters of the hospitals provide actual costs and the remainder report costs estimated using Medicare cost-to-charge ratios. Costs include fixed costs such as room and board, labor, and variable costs such as supplies, medications, etc.

Study design and criteria

Outcomes were evaluated for three types of encounters: ED visits, simple inpatient admissions, and complex inpatient admissions. The primary outcomes evaluated were cost, length of stay (LOS), mortality at discharge and rates of inpatient readmission and repeat ED visits within 60 days. Encounters were required to meet the following criteria: (1) occurred January 1, 2005 to September 30, 2008, (2) had a primary discharge diagnosis of COPD, (3) the patient was ≥65 years of age at the time of service, and (4) Medicare was listed as the payor. A diagnosis of COPD was identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for chronic bronchitis (491.xx), emphysema (492.xx), or unspecified chronic airway obstruction (496.xx). Encounters were excluded if the record contained a secondary diagnosis code for respiratory cancer, cystic fibrosis, fibrosis due to tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, pneumoconiosis, pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary tuberculosis or sarcoidosis.

A simple inpatient admission was defined as an admission that did not involve intubation or an intensive care (ICU) stay. A complex inpatient admission was defined as one that involved an ICU stay or intubation. A stay in a general, surgical or medical intensive care ward was counted as an ICU stay; stays in a cardiac or other specialty intensive care unit were not counted in order to ensure that the admissions counted were primarily related to COPD and not a cardiac condition. Intubation was identified using ICD-9-CM procedure codes, CPT codes or standard charge codes available in the Premier data set. Complex admissions were categorized as (1) intubation/no ICU, (2) ICU/no intubation or (3) ICU/intubation.

For each ED visit and admission, a patient comorbidity score was calculated using the Dartmouth-Manitoba adaptation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index, an algorithm that is based on diagnosis codes in administrative data for 19 morbidities and is predictive of 1-year mortality riskCitation18,Citation19. The Charlson score (range of 0–33) was calculated after excluding COPD codes, since COPD was the disease of interest. Additional comorbidity variables were created based on secondary diagnosis codes for asthma, cardiovascular disease, depression, lower respiratory tract infection, and upper respiratory tract infection. Respiratory and non-respiratory drugs dispensed were identified using standard charge codes.

Analysis

Mean costs (medical, pharmacy and total) for each encounter type were calculated. Mortality at discharge and length of stay (LOS) for inpatient admissions also were calculated. In addition, rates of inpatient readmissions and repeat ED visits were calculated. The latter outcomes were calculated at the patient level, but for all other analyses, the unit of analysis was the encounter. In assessing readmission rates, the first ED visit or inpatient admission during the year was designated as the index event. For privacy protection purposes, the Premier dataset contained month but not day of service for each encounter. A sequencing variable created at the institutional level designates the temporal order of encounters when multiple encounters occur in the same month. In this analysis, readmissions and repeat ED visits were defined as encounters with any diagnosis that occurred after the COPD-related index event, either in the same month or the month following; thus the follow-up period ranged from 30 to 60 days. However, rates of readmissions and repeat ED visits for 2005, 2006 and the first half of 2007 were based only on subsequent encounters occurring in the month following the index event due to unavailability of a sequencing variable for that time period; this precluded determination of the temporal order of encounters occurring within the month of the index event.

The study presents descriptive data for 2008 and summary data for 2005 to 2008. To compare costs across years and account for inflation, costs in 2005–2007 were adjusted to 2008 levels using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index (US Department of Labor). Counts and percentages were determined for categorical variables and mean ± SD (standard deviation) were determined for continuous variables. Inferential statistical testing was not performed since this is a descriptive study of costs; comparisons between groups of patients or categories of healthcare utilization are not being made. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC, USA).

Results

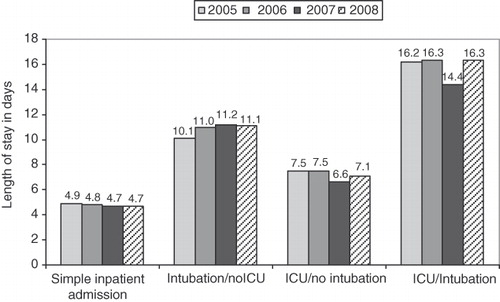

In 2008, 45,421 encounters met inclusion criteria. Of total encounters, 22.7% were ED visits, 56.3% were simple inpatient admissions and 5.4% were complex inpatient admissions (). The majority of complex admissions, 72.9%, involved intensive care but not intubation. The mean age of patients was 76 years and 57.2% were female (). Patients with an inpatient admission were approximately 1 year older and had a higher Charlson comorbidity score than patients with an ED visit. The mean Charlson comorbidity score was 0.46 (SD 0.81) for ED visits, 1.54 (1.63) for simple inpatient admissions, and 2.01 (1.85) for complex admissions. A total of 72.2% of simple hospital admissions and 84.4% of complex admissions for COPD had a secondary diagnosis of cardiovascular disease, compared to only 29.7% of ED visits. Lower respiratory tract infection was most commonly present in complex admissions (43.0% of admissions involving intensive care and intubation). The hospitals had a mean bed size of 361. Nearly one-third of all inpatient admissions occurred in teaching hospitals, compared to one-fourth of ED visits.

Figure 1. Contribution of each utilization category to total encounters, costs and deaths at discharge, 2008.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients by utilization category in 2008*.

Cost, length of stay and mortality

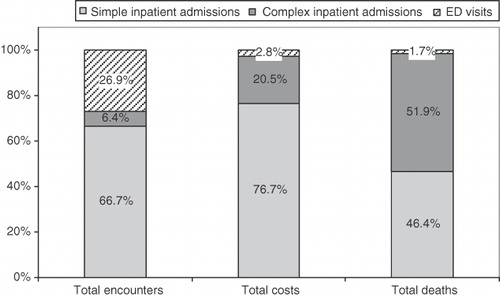

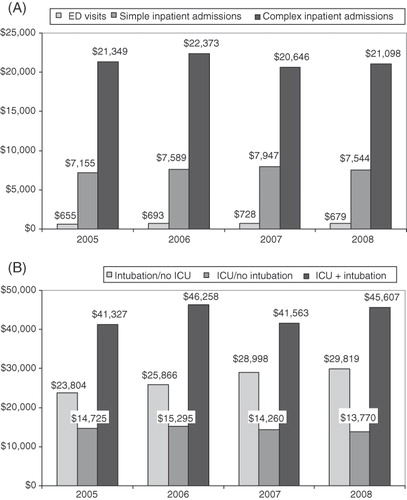

The mean cost of ED visits was $679 (SD $399) (). Simple admissions had a mean cost of $7,544 ($8,049) and LOS of 4.7 days (SD 3.4). The average LOS for complex admissions was nearly twice as long, 9.1 (9.2) days and mean cost was nearly three times higher ($21,098 [$46,160]). Complex admissions involving an intubation procedure were particularly costly. The mean cost of an ICU/no intubation admission was $13,770 ($12,825), whereas an ICU/intubation admission was $45,607 ($94,794) and an intubation/no ICU admission was $29,819 ($44,328). The increased cost for complex admissions involving intubation was partly driven by a higher mean length of stay. This was 16.3 (13.7) days for ICU/intubation admissions and 11.1 (11.3) days for intubation/no ICU admissions, compared to only 7.1 (6.0) days for admissions with ICU care but not intubation. Intubation/no-ICU admissions were also relatively expensive because the majority of these admissions involved a cardiac care unit stay (cardiac care unit was not included in the ICU variable in order to ensure that ICU admissions were attributable to COPD and not to a coronary condition). Medications accounted for 5.7% of the cost of ED visits, 10.6% of the cost of simple inpatient admissions and 10.9% of the costs of complex admissions. For all encounters combined, respiratory medications account for approximately 35% of total medication costs. Simple inpatient admissions and complex admissions were associated with a death rate of 1.1% and 12.9%, respectively. The highest mortality occurred with intubation/no ICU admissions (42.1%), followed by ICU/intubation (33.0%) and ICU/no intubation (12.9%). About half of the 202 intubation/no ICU admissions involved care in a cardiac unit, which may partly explain the higher mortality among these admissions.

Table 2. Cost and characteristics of hospital-based care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 2008.

Respiratory medication use

Use of respiratory and non-respiratory is shown in . The most common class of respiratory medications dispensed during ED visits and admissions was oral/IV corticosteroids (66.3% of all encounters), followed by antibiotics (59.3%) and the short-acting anticholinergic ipratropium (44.4%). Controller medications were dispensed in less than 2% of ED visits and approximately 12–30% of hospitalizations. The most common controller medications used during simple and complex inpatient admissions were inhaled corticosteroid plus long-acting β-adrenergic agonist combination (dispensed in 30.3% and 31.1% of simple and complex admissions, respectively), followed by long-acting anti-cholinergics (26.7% and 30.9%) and inhaled corticosteroids (11.6% and 13.6%).

Table 3. Utilization of respiratory and non-respiratory medications in COPD-related emergency department visits and inpatient admissions.

Readmissions

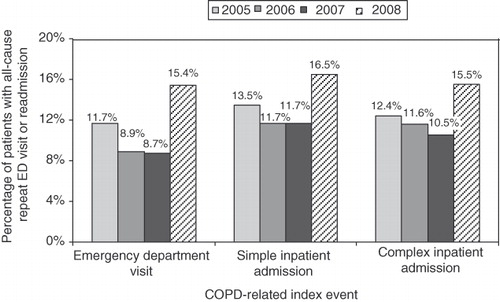

Altogether, 15.4% of patients with an initial ED visit in 2008 had a repeat ED visit. A similar percentage of hospitalized patients (15.5–16.5%) had a readmission with any discharge diagnosis within 60 days ().

Table 4. Rates of repeat emergency department visits and hospital readmissions, 2008.

Trends over time

The mean cost per encounter, adjusted for inflation, increased or decreased modestly for most types of encounters between 2005 and 2008, including simple admissions and all complex admissions combined (). However, the cost of intubation/no ICU admissions increased by 25.3% and the cost of ICU/intubation admissions increased by 10.4% during this time period. Between 2005 and 2008, LOS increased slightly for intubation/no ICU admissions, but trends in LOS were relatively flat for other types of inpatient admissions and for ED visits (). Trends in readmissions are shown in . Rates of readmission and repeat ED visits occurring in the month following the index event month were relatively stable from 2005 to 2006; higher rates seen in 2007 and 2008 are likely due to the additional capture of repeat encounters that occurred in the index event month; these encounters were captured for the last half of 2007 and for 2008.

Figure 2. Mean cost ($US) of emergency department visits and inpatient admissions, 2005–2008, adjusted to 2008 dollars. (A) Emergency department visits, simple admissions and complex admissions. (B) Complex admissions by type.

Figure 4. Rates of repeat emergency department visit or inpatient readmission within 60 days, 2005–2008. Rates in 2005 through first half of 2007 are based on encounters in the month following the index event month; rates in last half of 2007 and in 2008 are based on encounters in the index event month (post-index event) and the following month.

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis, data from 602 US hospitals were used to identify costs of hospital-based care for COPD, as well as LOS, mortality at discharge, and readmission rates, in a population of Medicare enrollees 65 years of age and older. Using hospital costs rather than billed charges, the study found a mean cost in 2008 of $679 for ED visits, $7,544 for simple inpatient admissions and $21,098 for complex admissions (requiring ICU or intubation). These are similar to mean costs reported by Stanford and colleagues, based on data from 218 US hospitals, of $571 for ED visits in 2001, or $762 in 2008 dollars; $5,997 for simple admissions in 2001, or $8,003 in 2008 dollars; and $16,428 for complex admissions, or $21,924 in 2008 dollarsCitation20. Of interest, reported costs of the present study, derived from actual hospital cost data, are substantially higher than the costs reported by researchers who applied Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates to national utilization dataCitation21. In that study, derived costs were $237 and $2,361 for COPD-related ED visits and hospitalizations, respectively, in 1994, or $409 and $4,074 after adjustment to 2008 dollars. This disparity highlights the value of understanding costs from the hospital perspective, as well as the third-party payor perspective. The present study found that admissions involving intubation, with or without intensive care, were the most expensive admissions. Intubation might simply serve as a marker of disease severity, and greater disease severity would be expected to require more costly care. For example, a prior population-based study found the median annual cost of hospitalization in patients with severe COPD was approximately 2.5 times higher than that of patients with moderate diseaseCitation12. Costs of ED visits and simple admissions in 2005–2008 remained relatively stable across years, while costs for complex admissions involving intubations increased substantially, even though LOS did not increase proportionately.

Much of the hospital-based care for COPD is for treatment of exacerbations, which occur an average of one to three times a year in patients with moderate-to-severe diseaseCitation15,Citation16. In this study, oral/IV corticosteroids, which are a common treatment for exacerbations of COPD, were dispensed in more than 85% of inpatient admissions and 54% of ED visits in 2008. This suggests that a large portion of the care captured in this analysis was for treatment of exacerbation events. In addition to being costly, exacerbations are associated with adverse long-term consequences, including an accelerated decline in lung function and reduced quality of lifeCitation22,Citation23. Previous research has shown that having an exacerbation is also a predictor of subsequent exacerbationsCitation23. Thus, preventing exacerbations and readmissions is a primary concern in managing COPD patients. Adequate maintenance pharmacotherapy, which requires both medication access and patient adherence, has been shown to reduce exacerbations and may reduce costs as well. In a study of Medicare beneficiaries with COPD (conducted before the advent of Medicare Part D), prescription drug coverage, a conduit for access, was associated with 29% lower spending on physician services and 23% lower spending on hospitalizations (although the latter finding was not statistically significant)Citation3. The present study findings indicate that repeat ED visits and hospital readmissions remain a challenge. For the calendar year 2008, rates of readmission within 60 days were 15.5–16.5%. This is similar to the 15% 60-day readmission rate reported previously by Stanford et al.Citation20. Examining a longer time period, Soriano and colleagues found a 24.3% readmission rate within a year of dischargeCitation24.

Inpatient mortality also remains substantial for patients with COPD. The rate of mortality at discharge in this study was 10.3% for admissions requiring intensive care and/or intubation, close to the rate for the same types of admissions reported by Stanford for 2000–2001 (10.4%)Citation20. A study with longer follow-up reported that 13.2% of the COPD reference group died within a year of dischargeCitation24.

The present study has some limitations. First, although the database used was relatively large, comprising inpatient data from more than 600 hospitals, unique patients could not be followed across different hospitals, and this may have resulted in an underestimate of readmissions and repeat ED visits. Also, because data capture was more complete in the second half of 2007 and in 2008 than in earlier periods, the readmission rates in 2005–2006 and 2007–2008 are not comparable. Secondly, the hospitals in the Premier database represent all regions of the United States, but are primarily not-for-profit hospitals, thus the data may not be generalizable to other types of hospital. Thirdly, administrative databases, while useful for capturing costs, diagnoses, and procedures, do not contain behavioral and clinical data, such as smoking status and spirometry test results. This prevents ascertainment of disease severity and other risk factors that may impact findings. It also was not possible to review paper or electronic medical records of patients to verify diagnoses, treatments and encounters. Finally, the present study examined only costs and utilization associated with COPD-related inpatient admissions and ED visits; outpatient care, outpatient pharmacy and long-term oxygen therapy were not evaluated, nor were non-COPD-related utilization and costs examined. An advantage of the present study is the capture of standardized actual costs incurred by hospitals, as opposed to billed charges, permitting analysis from the hospital perspective.

Conclusion

This study describes the hospital costs of COPD treatment in the ED and inpatient setting in a population of Medicare enrollees. Changes in COPD treatments as well as the advent of Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage warranted an updated assessment of hospital-based costs of care, which are a major driver of the total costs of medical care for patients with COPD. These costs remain substantial and have not decreased in recent years, in spite of the availability of newer treatments that can reduce exacerbations and the improved access to prescription drugs provided by Medicare Part D coverage. Hospitalizations in COPD patients that require intensive care or intubation are especially costly and associated with higher mortality. Additional research that focuses on patients in the ICU or intubation setting and their treatment history and comorbidity factors would be valuable, as well as evaluation of how undertreatment of COPD and patient adherence to therapy may impact on the costs of hospital-based care and readmission rates.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).

Declaration of financial/other relationships

A.A.D. has disclosed that he is an employee of GSK and owns company stock; M.S. and A.O.D. have disclosed that they are employees of Xcenda, LLC, a company that received funding from GSK to conduct this research. P.R. has disclosed that she has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Judith Hurley, MS, Hurley Health and Medical Communications, provided medical writing services, which were financially compensated by GSK.

References

- Celli BR, MacNee W. ATS/ERS Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 2004;23:932-946

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. Gig Harbor, WA: Medical Communications Resources, Inc.; December 2009. URL: www.goldcopd.com

- Stuart B, Doshi JA, Briesacher B, et al. Impact of prescription coverage on hospital and physician costs: a case study of Medicare beneficiaries with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Ther 2004;26:1688-1699

- Center on an Aging Society. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A chronic condition that limits activities. Data Profile 2002;6:1-6

- Gelberg J, McIvor RA. Overcoming gaps in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in older patients: new insights. Drugs Aging 2010;27:367-375

- Chi MJ, Lee CY, Wu SC. The prevalence of chronic conditions and medical expenditures of the elderly by chronic condition indicator (CCI). Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2010; published online 7 May 2010, doi:10.1016/j.archger.2010.04.017

- Menzin J, Boulanger L, Marton J, et al. Economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a Medicare population. Respir Med 2008;102:1248-1256

- Grasso ME, Weller WE, Shaffer TJ, et al. Capitation, managed care, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:133-138

- Mapel DW, Hurley JS, Frost FJ, et al. Health care utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A case-control study in a health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2653-2658

- Foster TS, Miller JD, Marton JP, et al. Assessment of the economic burden of COPD in the U.S.: a review and synthesis of the literature. COPD 2006;3:211-218

- Halpern MT, Stanford RH, Borker R. The burden of COPD in the U.S.A.: results from the Confronting COPD Survey. Respir Med 2003;97(Suppl C):81-89

- Hilleman DE, Dewan N, Malesker M, et al. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of COPD. Chest 2000;118:1278-1285

- Marton JP, Boulanger L, Friedman M, et al. Assessing the costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the state Medicaid perspective. Respir Med 2006;100:996-1005

- Miller JD, Foster T, Boulanger L, et al. Direct costs of COPD in the U.S.: an analysis of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data. COPD 2005;2:311-318

- Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, et al. Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:1608-1613

- Strassels SA, Smith DH, Sullivan SD, et al. The costs of treating COPD in the United States. Chest 2001;119:344-352

- National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Morbidity and Mortality: 2007 Chartbook on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Diseases. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-383

- Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1075-1079

- Stanford RH, Shen Y, McLaughlin T. Cost of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the emergency department and hospital. Treat Respir Med 2006;5:343-349

- Ward MM, Javitz HS, Smith WM, et al. Direct medical cost of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the U.S.A. Respir Med 2000;94:1123-1129

- Donaldson GC, Seemungal TAR, Bhownmik A, et al. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2002;57:847-852

- Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Paul EA, et al. Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:1418-1422

- Soriano JB, Kiri VA, Pride NB, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids with/without long-acting beta-agonists reduce the risk of rehospitalization and death in COPD patients. Am J Respir Med 2003;2:67-74