Abstract

Objective:

To estimate, from a third-party payer's perspective, the effects of switching from escitalopram to citalopram, after the generic entry of citalopram, on hospitalization and healthcare costs among adult MDD patients who were on escitalopram therapy.

Methods:

Adult MDD patients treated with escitalopram were identified from Ingenix Impact claims database. MDD- and mental health (MH)-related hospitalization rates and healthcare costs were compared between ‘switchers’ (patients who switched to citalopram after its generic entry) and ‘non-switchers’. MDD- and MH-related outcomes were defined as having a primary or a secondary diagnosis of ICD-9-CM = 296.2x, 296.3x and ICD-9-CM = 290–319, respectively. A propensity score matching method that estimated the likelihood of switching using baseline characteristics was used. Outcomes were examined for both 3-month and 6-month post-index periods.

Results:

The sample included 3,427 matched pairs with balanced baseline characteristics. Switchers were more likely to incur an MDD-related (odds ratio [OR] = 1.52) and MH-related hospitalization (OR = 1.34) during the 6-month post-index period (both p < 0.05). Compared to switchers, non-switchers had significantly lower MDD- and MH-related hospitalization costs ($248.3 and $219.8 lower, respectively) and medical costs ($277.4 and $246.4 lower, respectively) (all p < 0.05). Although non-switchers had significantly higher MDD- and MH-related prescription drug costs, overall they had significantly lower total MDD- and MH-related healthcare costs ($109.9 and $93.6 lower, respectively; both p < 0.001). The 3-month results were consistent with these 6-month findings.

Limitations:

The study limitations included limited generalizability of study findings, inability to differentiate switching from escitalopram to citalopram due to medical reasons versus non-medical reasons, and exclusion of indirect costs from cost calculations.

Conclusions:

Compared to patients maintaining on escitalopram, switchers from escitalopram to citalopram experienced higher risk of MDD- and MH-related hospitalization and incurred higher total MDD- and MH-related healthcare costs. The economic consequences of therapeutic substitution should take into account total healthcare costs, not just drug acquisition costs.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common and chronic health conditions in the world. About 17.1 million people in the United States (US) were reported to have MDD in the year 2004, and it is projected by the World Health Organization that by the year 2020, MDD will be the second leading cause of disability after ischemic heart diseaseCitation1,Citation2. The risk of relapse and recurrence in MDD exceeds 80%, and patients may experience further episodes on average four more times during their lifetime after having had a first episodeCitation3. MDD also imposes a substantial economic burden on society and on the individuals suffering from the diseaseCitation4,Citation5, which was estimated at $83.1 billion/year in the US in 2000, with $26.1 billion resulting from direct medical costs, $5.4 billion related to suicide-related mortality costs, and $51.5 billion in workplace costsCitation5.

Antidepressants are currently the mainstay in the treatment of MDD. The most widely used medications for MDD are the second-generation antidepressants, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). SSRIs and SNRIs have been shown to be clinically better tolerated and more effectiveCitation6, and also more cost-effective in long-term MDD treatment than older antidepressants (including all tricyclics and monoamine oxidase inhibitors)Citation7–10. Other medications used to treat MDD include agents that impact the reuptake of dopamine and adjunctive use of atypical antipsychotics.

Citalopram and escitalopram are members of the SSRI family and escitalopram is the pure S-enantiomer of the racemic citalopram. An enantiomer is composed of two compounds that are non-superimposable mirror images of each other. Citalopram is a racemate that comprises a 1:1 mixture of S (+)-enantiomer (escitalopram) and an R (−)-enantiomer (R-citalopram). It is the S-enantiomer that possesses the pharmacological effect of the drug. The R-enantiomer in citalopram counteracts the activity of the S-enantiomer, which may be the underlying reason for the differences in the pharmacological and clinical effects between escitalopram and citalopramCitation11–13. Escitalopram was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for acute and maintenance treatment of MDD in adults in the year 2002Citation14; approved for acute treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder in 2003; and approved for acute and maintenance treatment of MDD in adolescents aged 12–17 in 2009. Citalopram was approved by the FDA for acute and maintenance treatment of adults with MDD in 1998 (its sole indication)Citation15.

Compared to other second-generation antidepressants (e.g., citalopram, fluoxetine, venlafaxine, and duloxetine), escitalopram had better adherence and was associated with lower urgent-care utilization and lower total healthcare costsCitation16. Results from randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that escitalopram 10–20 mg/day was highly efficacious in the treatment of acute MDD among adult patients aged 18–65Citation17–19. Several studies have found that compared to citalopram, escitalopram was more efficacious (p < 0.05), had a faster onset of action (p < 0.05), and a better symptomatic control of depression and anxiety (as measured by the change in the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale [MADRS] inner tension item)Citation18,Citation20–26. Escitalopram is also well tolerated, with lower discontinuation rate and superior response rates compared to citalopram. For example, results from a pooled analysis comparing efficacy of equivalent doses of escitalopram and citalopram showed that a significantly greater number of patients responded to escitalopram (≥50% decrease from baseline in MADRS total score; p = 0.009) and had higher remission rates (MADRS total score ≤ 12; p = 0.044)Citation24. Additionally, cost-effectiveness studies comparing escitalopram with citalopram have generally shown that citalopram was dominated by escitalopram and that the use of escitalopram was associated with favorable economic outcomesCitation27–30. For example, Sullivan et al. showed that escitalopram was associated with lower expected treatment costs ($3,891 [95% CI: $2,486–$5,161] vs. $3,938 [95% CI: $2,529–$5,219]). Effectiveness as measured by quality-adjusted life years was slightly higher for escitalopram (0.341 [0.184–0.479]) compared with citalopram (0.340 [0.183–0.477])Citation30.

Due to increasing healthcare costs, switching patients to cheaper generic alternatives from branded products is one of the cost-cutting measures adopted by healthcare systems. This is often encouraged by the use of step-edits, prior authorizations, and tiered co-payment benefit designsCitation31. Generic substitution can occur in two ways: substitution with the same compound and substitution with a different compound within the same class after it becomes generic (i.e., therapeutic substitution). In both cases, because the generic drug and substituted drug may have different efficacy and safety profiles, the intention of lowering drug costs by switching from a branded medication to a generic medication may be at the risk of not maintaining the therapeutic efficacy and thus may lead to higher healthcare utilization and costs over the long termCitation31–36. For example, several case studies have reported recurrences of symptoms and new adverse events after generic substitutions with the same compoundCitation33,Citation34. In addition, a recent study on therapeutic substitution revealed that patients who were switched from one brand SSRI to a different generic SSRI incurred more urgent-care utilization and higher MDD-related medical costs ($151; p < 0.05) compared to those who remained on the brand SSRICitation36. The current study aims to investigate the economic consequences of a therapeutic substitution of escitalopram with citalopram.

Generic versions of citalopram became available on October 28, 2004, which may have led to switching MDD patients from escitalopram to citalopram, owing to lower drug costs. Because citalopram and escitalopram are chemically related, payers may assume that they provide similar clinical benefits and that the lower acquisition cost of generic citalopram will lead directly to reduction in overall treatment costs. However, citalopram and escitalopram are different medications and are not bioequivalent. Substitution of escitalopram with citalopram is considered therapeutic substitution. Patients who responded well to escitalopram and were then switched to citalopram may experience suboptimal outcomes due to the therapy interruption. The present study evaluates the economic outcomes of MDD patients who were treated with escitalopram and were switched to citalopram following the expiration of its patent exclusivity.

Methods

Data source

A retrospective data analysis was conducted using administrative claims data from the Ingenix Impact National Managed Care Database, a data source with the combined claims of more than 45 health plans representing approximately 30 million covered lives in 2007 in the US. The database contains enrollment records, medical claims (type of service, ICD-9 diagnosis code, CPT procedure code, standardized payments) and prescription drug claims (NDC code, days of supply, dose strength, and standardized payments). This study included all medical and pharmacy claims for enrollees during the time frame between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2007. The starting date of the data sample is January 1, 2003 because escitalopram received FDA approval for the treatment of MDD in August 2002. The dataset included information on mental carve-out eligibility, which indicates whether mental health services were covered by another health plan, thereby permitting the study sample to be limited to patients with complete mental service records (i.e., patients with no mental carve-out service), and therefore avoid underestimating the true economic burden of depression.

Sample selection

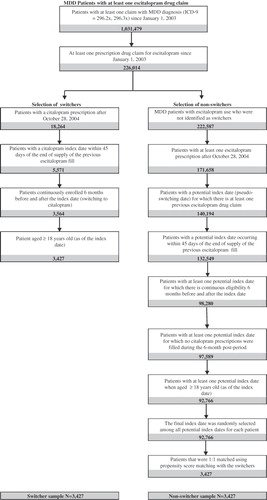

Adult MDD patients treated with escitalopram were identified in the database. They were required to have (1) at least one claim with MDD diagnosis (ICD-9-CM = 296.2x, 296.3x) since January 1, 2003 and (2) at least one prescription drug claim for escitalopram since January 1, 2003. These patients were then classified into two groups: patients who remained on escitalopram (non-switchers) and those who switched to generic citalopram (switchers), which is defined as citalopram prescribed after its generic entry (i.e., after October 28, 2004). Selection of switchers was based on the following criteria: (1) patients with a citalopram prescription after October 28, 2004; the first prescription fill date of citalopram (index date) must be within 45 days of the end of supply of the previous escitalopram fill; (2) continuously enrolled 6 months prior to the index date and 6 months after; and (3) age ≥18 years old (as of the index date).

The remaining MDD patients fulfilling the following criteria were classified as non-switchers: (1) having at least one escitalopram prescription fill after October 28, 2004; with at least one prescription fill date of escitalopram (potential index date) falling within 45 days of the end of supply of the previous escitalopram fill; (2) continuous eligibility 6 months before and after the potential index date; (3) no citalopram prescriptions were filled during the 6-month period after the potential index date; and (4) age ≥18 years old (as of the potential index date). Because there may be multiple potential index dates for a patient, the final index date was randomly selected among all potential index dates for each patient in the non-switcher group.

This study did not differentiate whether patients switched from escitalopram to citalopram due to medical reasons or non-medical reasons because the claims data had limited information to allow identification of reasons for switching. However, because all the switching in this study occurred after the date when citalopram became generic, it was assumed that the switching occurred due to lower drug acquisition cost of citalopram instead of medical reasons. The discussion section addresses how this assumption might impact the study results.

Propensity score matching

To reduce selection bias and ensure balanced baseline characteristics between the two study groups, switchers and non-switchers were matched 1:1 using propensity scoring technique (i.e., the likelihood of switching) estimated from a logistic regression model. The predicted value of switching was the propensity score assigned to each patient. The variables included in the regression were: (1) demographics (age, gender, and region); (2) insurance type (stratified by commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare); (3) mean length of escitalopram treatment prior to index date; (4) comorbidity profile, including Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index and individual comorbidities; and (5) healthcare resource utilization, total healthcare costs, total MH healthcare costs, and total MDD-related healthcare costs at baseline.

Outcomes

The outcomes measured in this study included urgent-care resource utilization and healthcare costs. Urgent-care resource utilization included both hospitalizations and emergency room (ER) visits. Hospitalizations were evaluated using both rate of hospitalization and number of hospitalization days. Similarly, ER visits were evaluated using the rate of any ER visit and number of ER visits. Healthcare costs were broken down into prescription drug costs, medical costs (which included urgent- and non-urgent-care related costs), and total costs, which consisted of the prescription drug and medical costs. All costs were adjusted to 2007 US dollars using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index.

All outcomes were measured during the 6-month study period and were broken down into all-cause, mental health (MH)-related, and MDD-related. All-cause outcomes included utilization and costs for any reason or any prescription drug use during the pre-defined study period. MH-related utilization and costs were defined as those with a primary or a secondary diagnosis of ICD-9-CM = 290–319. MH-related prescription drugs included first and second-generation antidepressants, typical and atypical antipsychotics, anti-anxiety agents, hypnotics, psychotherapeutics, and neurological agents. MDD-related utilization and costs were defined as those with a primary or a secondary diagnosis of ICD-9-CM = 296.2x and 296.3x while MDD-related prescription drugs included all antidepressants (including the adjunctive use of atypical antipsychotics).

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics, including demographics, length of escitalopram treatment prior to index date, comorbidities, healthcare utilization, and healthcare costs, were measured over the 6-month baseline period. Baseline characteristics and all outcomes were compared descriptively between the two groups using Wilcoxon signed rank tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Conditional logistic regression was used to adjust matched switcher and non-switcher pairs and compare the likelihood of experiencing a hospitalization or ER visit. Both unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR) were reported. Unadjusted OR was estimated based on conditional logistic regression analysis that controls for the matched pairs while adjusted OR was estimated based on conditional logistic regression analysis that controls for the matched pairs and the corresponding urgent-care utilization during the 6-month baseline period.

Sensitivity analysis

Propensity score matching created samples of switchers and non-switchers with balanced baseline characteristics and allowed valid direct comparison of urgent-care utilization and healthcare costs between the two cohorts in the post-index study period. In order to further test the robustness of the results, two sets of sensitivity analyses were performed. First, a difference-in-difference (DID) analysis was used to study the changes in costs from baseline to the 6-month post-index period between the two cohorts. Similar statistical analyses as described above were conducted. As a second set of sensitivity analyses, all the analyses were repeated measuring the outcomes for a 3-month post-index period, to evaluate the immediate impact of switching on healthcare utilization and costs. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 226,014 patients were identified in the database with an MDD diagnosis who initiated escitalopram since January 1, 2003. Among these patients, 3,427 patients met the inclusion criteria for the switchers group and 92,766 patients met the inclusion criteria for the non-switchers. The final sample size consisted of 3,427 pairs of 1:1 matched switchers and non-switchers based on propensity score. summarizes the sample counts by selection criteria.

Overall, the mean age of the final sample cohort was 45.1 years, the proportion of males was 26.5%, and the mean length of escitalopram treatment prior to the index date was 372 days. No significant differences were observed between the propensity-score matched switchers and non-switchers in terms of baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidity profiles, baseline healthcare utilization, and costs ().

Table 1. Comparison of baseline characteristics between propensity score-matched switchers and non-switchers*.

Urgent-care resource utilization

During the 6-month post-index period, the unadjusted rates of urgent-care visits and hospitalizations were significantly higher among switchers. Switchers were more likely to have an MDD-related urgent-care utilization than non-switchers (odds ratio [OR] = 1.43; p = 0.0016) or a MH-related urgent-care utilization (OR = 1.27; p = 0.0035) (). Switchers also had higher rates of hospitalization related to any cause (OR =1.18; p = 0.0326), MDD-related hospitalization (OR = 1.52; p = 0.0035), and MH-related hospitalization (OR = 1.43; p = 0.0007). The rate of MDD-related (p = 0.2743) and MH-related (p = 0.5066) ER visits did not differ significantly between the two cohorts.

Table 2. Comparison of urgent-care utilization between propensity-score matched switchers and non-switchers.

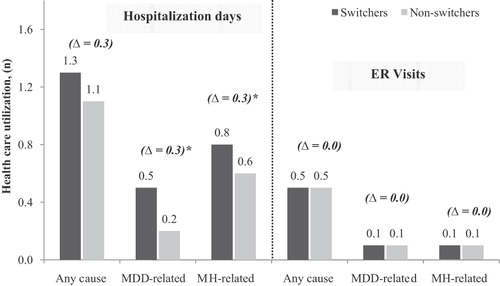

The results were similar after controlling for the corresponding urgent-care utilization during the 6-month baseline period (). Switchers were more likely to have MDD-related (OR = 1.35; p = 0.0337) and MH-related urgent-care utilization (OR = 1.23; p = 0.0325). Particularly, they were more likely to have an MDD-related (OR = 1.52; p = 0.0181) and MH-related hospitalization (OR = 1.34; p = 0.0209). Switchers also had significantly more MDD-related (0.3; p = 0.0184) and MH-related (0.3; p = 0.0080) hospitalization days compared to non-switchers (). No significant differences in the number and rates of ER visits were observed between switchers and non-switchers.

Figure 2. Comparison of hospitalization days and number of ER visits between propensity-score matched switchers and non-switchers. Healthcare utilization was measured over the 6-month post-index period.*p < 0.05; p-values based on Wilcoxon signed rank tests; MDD = major depressive disorder; MH = mental health.

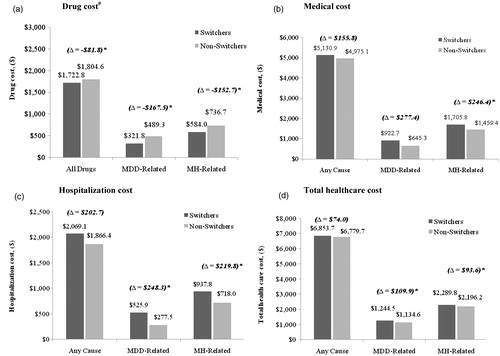

Healthcare costs

Prescription drug costs were significantly lower for switchers compared to non-switchers (). The total prescription drug cost was $81.8 lower, the MDD-related cost was $167.5 lower, and the MH-related prescription drug costs were $152.7 lower (all p < 0.0001). However, switchers incurred higher total MH-related medical costs ($1,705.8 vs. $1,459.4; p = 0.0235) compared to non-switchers (). Total all-cause medical cost was $155.8 higher, and MDD-related cost was $277.4 higher, although not statistically significant.

Figure 3. Comparison of healthcare costs between propensity-score matched switchers and non-switchers. Healthcare costs were measured over the 6-month post-index period. #Excluding prescriptions for the index therapy (escitalopram or citalopram). *p < 0.05; p-values based on Wilcoxon signed rank tests; MDD = major depressive disorder; MH = mental health.

The increase in the total medical costs in the switchers group was primarily driven by an increase in the hospitalization costs (). Compared to non-switchers, switchers incurred higher MDD-related ($525.9 vs. $277.5; p = 0.0216) and higher MH-related ($937.8 vs. $718.0; p = 0.0114) hospitalization costs. All-cause hospitalization cost was also higher for switchers, although the difference was not statistically significant. Overall, compared to non-switchers, switchers incurred $109.9 significantly higher total MDD-related ($1,244.5 vs. $1,134.6; p < 0.0001) and $93.6 higher total MH-related healthcare costs ($2,289.8 vs. $2,196.2; p < 0.0001) in the 6-month post-index period. Total all-cause health costs were comparable between the two groups ().

Sensitivity analysis

Difference-in-difference analysis

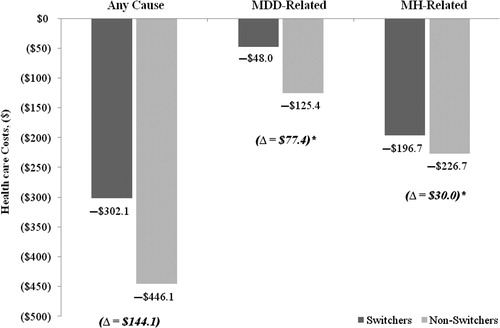

Results from the difference-in-difference analysis were consistent with findings from the previous analysis. Switchers had lower MDD-related and lower MH-related prescription costs (both p < 0.0001), which were offset by an increase in the medical costs. Compared to non-switchers, switchers had $276.9 higher medical costs related to any cause (p = 0.1733), $243.9 higher MDD-related medical costs (p = 0.0297), and $181.0 higher MH-related medical costs (p = 0.0485). Switchers also had $144.1 higher total healthcare costs related to any cause (−$302.1 vs. −$446.1; p = 0.8428), $77.4 higher total healthcare costs related to MDD (–$48.0 vs. −$125.4; p < 0.0001), and $30 higher total healthcare costs related to MH (–$196.7.0 vs. −$226.7; p < 0.0001) ().

Figure 4. Comparison of changes in total healthcare costs from baseline to the post-index period between propensity-score matched switchers and non-switchers. Change represents the difference between the 6-month post-index period costs and the average 6-month costs for the baseline period. *p < 0.05; p-values based on Wilcoxon signed rank tests; MDD = major depressive disorder; MH = mental health.

3-month results

Overall, the 3-month results were consistent with the 6-month findings. Compared to non-switchers, switchers had significantly higher rates of MDD-related (4.4% vs. 2.5%) and MH-related urgent-care utilization (7.6% vs. 5.6%) (both p < 0.001). They also had significantly higher MDD-related and MH-related hospitalization costs during the 3-month study period, significantly higher MDD-related medical costs ($543.1 vs. $314.8), and MH-related medical costs ($968.9 vs. $746.4), and significantly higher total MDD-related healthcare costs ($721.7 vs. $594.9) and MH-related healthcare costs ($1,283.5 vs. $1,156.6) ().

Table 3. Comparison of 3-month healthcare costs between propensity-score matched switchers and non-switchers.

Discussion

Adult MDD patients who were switched from escitalopram to generic citalopram had significantly higher urgent-care utilization and higher MH-related and MDD-related healthcare costs over the 6-month study period, compared to patients who continued treatment with escitalopram. The increases in healthcare utilization and costs were primarily driven by increases in hospitalization. The differences in hospitalization cost between switchers and non-switchers accounted for approximately 90% of the differences in total MDD- or MH-related medical costs. Although prescription drug costs were significantly reduced by switching to generic citalopram, the reduction was more than offset by higher medical costs among switchers. The findings suggest that at least some patients who were switched from brand escitalopram to generic citalopram may have experienced suboptimal clinical outcomes that required additional hospitalization and other medical services. Therefore, despite the savings in pharmacy costs, the switching eventually led to higher total mental healthcare costs for payers.

The increase in medical costs may result from the suboptimal effects (e.g., reduced response or increased adverse reactions) of generic citalopram among at least some of the switchers. Several studies have shown that escitalopram demonstrated higher efficacy (e.g., change in MADRS score from baseline) compared to citalopramCitation22–25. A recent meta-analysis by Cipriani et al.Citation 26 showed that escitalopram had better efficacy (measured by 50% reduction in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale or MADRS scores from baseline) and acceptability (assessed by discontinuation due to lack of efficacy or side effects) compared to other generic SSRIs. Reduced acceptability with generic SSRIs could result in reduced treatment adherence and increase in MDD relapse and MDD-related costsCitation37,Citation38. Hence, determination of whether a therapeutic substitution is appropriate should be made on the basis of the empirical assessment of comparative treatment effectiveness and not just based on drug costsCitation31. For patients who responded well to escitalopram, therapeutic switching to citalopram causes unnecessary interruption in the continuity of treatment, which oftentimes leads to negative clinical outcomes, such as intolerance of or non-response to the new treatment. This will inevitably require more medical resources to be devoted to help switchers cope with the negative clinical outcomes and may also require switching back to escitalopram in order to maintain the clinical stability. It is also worth mentioning that patients’ perceptions, though not available in the claims data, are also likely to affect treatment outcomes and thus resource utilization and healthcare costs. It is possible that a higher proportion of switchers held positive beliefs about citalopram compared to non-switchers. Therefore, they may have responded better to citalopram compared to non-switchers.

This study's findings are consistent with those of a previous study that compared the effects of switching from escitalopram to an alternative generic SSRI due to non-medical reasonsCitation36. The study results indicated that patients switching to generic SSRI had significantly increased rates of all-cause and MH-related urgent-care hospitalization compared to those who were maintained on escitalopram (OR = 1.15 and 1.34, respectively). Switchers were also reported to have incurred $222 higher MDD-related medical costs compared to those patients that continued using escitalopram. Thus, patients who achieved stable response on one drug and then were switched to a different drug may lose the original response because the drug to which they were switched might not be as efficacious and may also suffer from unnecessary adverse reactions due to differences in tolerability profiles.

Driven by cost containment considerations, healthcare systems have adopted a variety of policies designed to encourage physicians and patients toward lower-cost drugs, including use of generic drugs when they become available. However, therapeutic substitution may undermine the original goal of cost saving, and instead, may increase cost of medical services and total healthcare costsCitation31,Citation36. The results from this study further support the argument that therapeutic substitution due to lower drug costs of generic medications may lead to increased healthcare utilization and total healthcare costs from the payer's perspective. Therefore, considerations of therapeutic substitution should be based on the clinical effects of the drugs instead of drug costs only. Patients who have received a therapy for a long time and responded well should continue that therapy instead of being switched to another low-cost therapy.

This study has several limitations in addition to the general ones associated with claims analysis. First, there may be unobserved confounding factors between patients maintained on escitalopram versus those who were switched to generic citalopram. However, in order to minimize selection bias, propensity score matching and regression methods were used, controlling for numerous patient baseline characteristics observable in claims data. As shown in the analysis, the baseline characteristics of the two study groups were well balanced after propensity score matching. Second, the study would ideally include patients who switched due to non-medical reasons only, but there was not enough information in the claims data to identify the reasons for switching. However, switching from escitalopram to citalopram due to medical reasons may be rare, especially after the generic citalopram became available. Inclusion of patients who switched due to medical reasons would have underestimated the actual differences between switchers and non-switchers because this group of patients would have had better outcomes in the study period if citalopram was the right treatment. Third, because of the limited information available in administrative claims data, this study was not able to examine the reasons for higher post-switching healthcare utilization and costs among switchers. Finally, indirect costs (e.g., costs associated with work productivity loss and caregivers’ time) were not included in the analysis of cost outcomes and may underestimate the costs presented.

Conclusion

This large retrospective claims data analysis suggests that compared to adult MDD patients maintained on escitalopram, patients who were switched from escitalopram to generic citalopram experienced higher risk of MDD-related and mental health-related hospitalization and incurred higher MDD-related and mental health-related healthcare costs. The study also suggests that savings in drug costs may be more than offset by the increase in medical costs among switchers.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Forest Laboratories, Inc.

Declaration of financial/other interests

A.P.Y., J.X., A.B., K.P., E.Q.W., and R.B.-H. have disclosed that they are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a company that received funding from Forest Laboratories, Inc. to conduct this study. S.B. and M.H.E. have disclosed that they are employees of Forest Laboratories, Inc.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy's Educational Conference in San Antonio, Texas, October 7–9, 2009.

References

- The National Survey on Drug Use and Health Report: Depression among adults, November 2005 Available at: http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k5/depression/depression.pdf Accessed on October 1, 2009

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349:1498-1504

- Judd LL. The clinical course of unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54:989-91

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003;289:3095-105

- Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:1465-75

- Weilburg JB. An overview of SSRI and SNRI therapies for depression. Manag Care 2004;13:25-33

- Panzarino PJ, JrNash DB. Cost-effective treatment of depression with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Am J Manag Care 2001;7:173-184

- Frank L, Revicki DA, Sorensen SV, et al. The economics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in depression: a critical review. CNS Drugs 2001;15:59-83

- Peveler R, Kendrick T, Buxton M, et al. A randomised controlled trial to compare the cost-effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and lofepramine. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:1-134, iii

- Revicki DA, Simon GE, Chan K, et al. Depression, health-related quality of life, and medical cost outcomes of receiving recommended levels of antidepressant treatment. J Fam Pract 1998;47:446-52

- Cipriani A, Santilli C, Furukawa TA, et al. Escitalopram versus other antidepressive agents for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD006532

- Kasper S, Sacher J, Klein N, et al. Differences in the dynamics of serotonin reuptake transporter occupancy may explain superior clinical efficacy of escitalopram versus citalopram. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2009;24:119-25

- Sánchez C, Bøgesø KP, Ebert B, et al. Escitalopram versus citalopram: the surprising role of the R-enantiomer. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:163-76

- Guideline watch: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder, 2nd edn. Available at: http://www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/pracGuideTopic_7.aspx. Accessed on October 1, 2009

- Celexa package insert, available at http://www.frx.com/pi/celexa_pi.pdf. Accessed on October 1, 2009

- Wu EQ, Greenberg PE, Yang E, et al. Treatment persistence, healthcare utilisation and costs in adult patients with major depressive disorder: a comparison between escitalopram and other SSRI/SNRIs. J Med Econ 2009;12:124-35

- Burke WJ, Gergel I, Bose A. Fixed-dose trial of the single isomer SSRI escitalopram in depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:331-36

- Lepola UM, Loft H, Reines EH. Escitalopram (10-20 mg/day) is effective and well tolerated in a placebo-controlled study in depression in primary care. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;18:211-17

- Murdoch D, Keam SJ. Spotlight on escitalopram in the management of major depressive disorder. CNS Drugs 2006;20:167-70

- Baldwin DS, Reines EH, Guiton C, et al. Escitalopram therapy for major depression and anxiety disorders. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:1583-92

- Baldwin DS. Escitalopram: efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of depression. Hosp Med 2002;63:668-71

- Gorman JM, Korotzer A, Su G. Efficacy comparison of escitalopram and citalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder: pooled analysis of placebo-controlled trials. CNS Spectr 2002;7:40-4

- Lam RW, Andersen HF. The influence of baseline severity on efficacy of escitalopram and citalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder: an extended analysis. Pharmacopsychiatry 2006;39:180-84

- Lepola U, Wade A, Andersen HF. Do equivalent doses of escitalopram and citalopram have similar efficacy? A pooled analysis of two positive placebo-controlled studies in major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;19:149-55

- Moore N, Verdoux H, Fantino B. Prospective, multicentre, randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy of escitalopram versus citalopram in outpatient treatment of major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2005;20:131-37

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:746-58

- Fantino B, Moore N, Verdoux H, et al. Cost-effectiveness of escitalopram vs. citalopram in major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007;22:107-15

- Wade AG, Toumi I, Hemels ME. A probabilistic cost-effectiveness analysis of escitalopram, generic citalopram and venlafaxine as a first-line treatment of major depressive disorder in the UK. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:631-42

- Sørensen J, Stage KB, Damsbo N, et al. A Danish cost-effectiveness model of escitalopram in comparison with citalopram and venlafaxine as first-line treatments for major depressive disorder in primary care. Nord J Psychiatry 2007;61:100-8

- Sullivan PW, Valuck R, Saseen J, et al. A comparison of the direct costs and cost effectiveness of serotonin reuptake inhibitors and associated adverse drug reactions. CNS Drugs 2004;18:911-32

- Greenberg PE. Does generic substitution always make sense? J Med Econ 2008;11:547-53

- Blier P. Brand versus generic medications: the money, the patient and the research. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2003;28:167-8

- Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Patterson B, et al. Symptom relapse following switch from Celexa to generic citalopram: an anxiety disorders case series. J Psychopharmacol 2007;21:472-6

- Mofsen R, Balter J. Case reports of the reemergence of psychotic symptoms after conversion from brand-name clozapine to a generic formulation. Clin Ther 2001;23:1720-3171

- Borgheini G. The bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of generic versus brand-name psychoactive drugs. Clin Ther 2003;25:1578-92

- Lauzon V, Kaltenboek A, Yu AP, et al. The economic impact of generic switching for patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) treated with escitalopram or a patented SSRI. Presented at ISPOR 14th Annual International Meeting. Value Health 2009;12:A179

- Panzer PE, Regan TS, Chiao E, et al. Implications of an SSRI generic step therapy pharmacy benefit design: an economic model in anxiety disorders. Am J Manag Care 2005;11:S370-9

- McLaughlin TP, Eaddy MT, Grudzinski AN. A claims analysis comparing citalopram with sertraline as initial pharmacotherapy for a new episode of depression: impact on depression-related treatment charges. Clin Ther 2004;26:115-24