Abstract

Objective:

To compare psychiatric-related healthcare resource utilization (inpatient facility admissions, emergency room visits and ambulatory visits) and costs (medical, pharmacy and total healthcare costs) in patients initiated on paliperidone extended release (ER), risperidone, aripiprazole, olanzapine, ziprasidone or quetiapine.

Methods:

This exploratory, retrospective administrative claims analysis database compared patients from a large US commercial health plan who were initiated on their index oral atypical antipsychotics between January 1, 2007, and June 30, 2007. Cohorts were assigned by first antipsychotic claim and propensity score–matched by age, gender, US census division, race, household income, baseline antipsychotic use, co-morbid conditions and psychiatric-related utilization. Psychiatric-related healthcare resource utilization and costs were measured for 6 months post-initiation. Descriptive analyses compared paliperidone ER with the other cohorts.

Results:

There were 562 patients in matched paliperidone ER (n = 95), risperidone (n = 94), aripiprazole (n = 94), olanzapine (n = 89), ziprasidone (n = 95) or quetiapine (n = 95) cohorts. The paliperidone ER cohort had fewer mean psychiatric-related ambulatory visits than the risperidone cohort (p = 0.05). The paliperidone ER cohort had significantly lower mean psychiatric-related medical costs than the olanzapine, quetiapine and ziprasidone cohorts (p < 0.05) and lower total costs than the ziprasidone and olanzapine cohorts (p = 0.02). No other outcomes were significantly different.

Limitations:

Small sample sizes and short post-index observation times due to the launch of paliperidone ER in January 2007, coupled with the inherent lag time with medical claims data, limit the generalizability of the study findings.

Conclusion:

Patients treated with paliperidone ER may have psychiatric-related utilization costs that are comparable to those of patients who initiated treatment with other oral atypical antipsychotics.

Introduction

Mental illnesses can be devastating diagnoses that bring enormous burdens to patients, families and society. The personal costs are high because many of these conditions are lifelong, typically beginning in adolescence or young adulthood, and are characterized by repeated relapseCitation1–5. Distressing symptoms and impaired cognitive and psychosocial functioning interfere with family relationships and the ability to maintain employment and are linked to a high risk of suicide. Further, mental illnesses are often accompanied by psychiatric or medical co-morbidities that can add considerably to the overall illness burdenCitation1,Citation2,Citation6–16. The societal costs of mental illness in the United States (US) are also substantial, with estimated total costs of $26.1 billion for depression (in 2000 US dollars)Citation17, $62.7 billion for schizophrenia (in 2002 US dollars)Citation18 and $10–45.2 billion for bipolar disorder (in 1998 US dollars)Citation19.

Atypical antipsychotics are effective medications that can reduce the burden of illness in patients with mental illnessesCitation20. For instance, oral atypical antipsychotics are usually recommended as first-line therapy for schizophreniaCitation21; they alleviate symptoms, improve functioning and prevent relapseCitation22–28. Multiple oral atypical antipsychotics are available in the US; however, they are not interchangeable. Differences in pharmacology, tolerability, safety and efficacy are considerations for appropriate medication selectionCitation29,Citation30. Health economic outcomes, such as resource use and costs, are additional indicators of the overall value of an individual atypical antipsychotic.

As costs related to mental illness are substantial, the managed-care community is interested in analyses of data on healthcare utilization and costs because they allow managed-care providers to make informed decisions based on a payer's perspective. Typically, these analyses are performed using databases of prescription claims; however, the wide variety of patients in a database requires that patients be matched according to specific characteristics so that analytic comparisons can be made among similar populations. Propensity score matching, considered the observation study analogue of randomization, is often utilized to create treatment groups that are balanced based on a large number of baseline characteristicsCitation31 and has been found to be effective in analyzing data from retrospective databasesCitation32,Citation33.

The purpose of this analysis is to compare psychiatric-related healthcare resource utilization (inpatient facility admissions, emergency room visits and ambulatory visits) and costs (medical, pharmacy and total healthcare costs) over a 6-month time period among patients in a large US healthcare plan who have had at least one pharmacy claim for paliperidone extended release (ER), risperidone, aripiprazole, olanzapine, ziprasidone or quetiapine using propensity score matching.

Methods

Data source

This retrospective claims analysis used medical and pharmacy data and enrolment information to compare outcomes for patients treated with paliperidone ER versus patients treated with aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone or ziprasidone. Data were from a proprietary administrative claims database affiliated with a large US commercial healthcare plan. The regions covered by the plan were New England (CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT), Mid-Atlantic (NJ, NY, PA), East North Central (IL, IN, MI, OH, WI), West North Central (IA, KS, MN, MO, ND, NE, SD), South Atlantic (DC, DE, FL, GA, MD, NC, SC, VA, WV), East South Central (AL, KY, MS, TN), West South Central (AR, LA, OK, TX), Mountain (AZ, CO, ID, MT, NM, NV, UT, WY) and Pacific (AK, CA, HI, OR, WA).

The plan provided fully insured coverage for professional (e.g., physician), facility (e.g., hospital) and outpatient prescription services. Medical claims included multiple diagnosis codes recorded with the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes; procedures recorded with ICD-9-CM procedure codes, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes; service site codes; facility revenue codes; and health plan–paid and patient-paid costs. After services were provided, approximately 6 months were required for complete medical data in the administrative claims database.

Pharmacy claims data provided National Drug Code, dosage form, drug strength, fill date, number of days’ supply and health plan–paid and patient-paid costs. Typically, pharmacy claims were added to the research database within 6 weeks of dispensing. Patient-related socioeconomic data included race, ethnicity and household income category. These patient data were derived from a match conducted by the healthcare plan against a marketing database maintained for a large segment of the US population; the match included health plan members enrolled in November 2005. Approximately 30% of the race data were collected directly from public records (e.g., driver's license records), while the remaining data were based on sophisticated algorithms using enhanced geocoding (e.g., address and census block data enhanced by onomastic rules). Household income was populated either by self-report or through predictive modeling. Sources for the self-reported economic measures included national surveys and consumer product registrations. Predicted household incomes were generated by modeling such factors as age, occupation, home ownership and median income from the block group census data.

Inclusion criteria

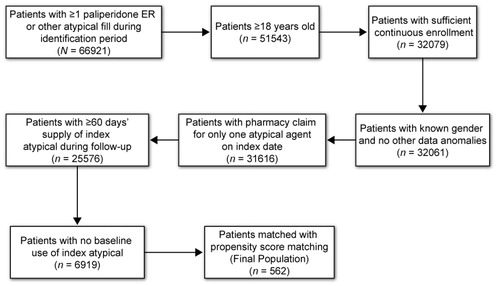

Patients included in this analysis were at least 18 years old, were commercial health plan members and had at least one pharmacy claim for oral paliperidone ER, aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone or ziprasidone between January 1, 2007, and June 30, 2007. All patients also had to be continuously enrolled in the healthcare plan for 6 months before (baseline) and after (follow-up) the index date (i.e., first observed prescription fill date; medication was defined as the index antipsychotic), had to have a minimum 60-day supply of their index antipsychotic during the follow-up period and had to have no pharmacy claims for their index antipsychotic during the baseline period. Patients were assigned to cohorts based on their index antipsychotic. Thus, patients were initiated on their index treatment but were not necessarily new to atypical antipsychotic treatment. A total of 562 patients met all criteria for study inclusion ().

Variables identified for this analysis

Patient variables identified from the study population included patient characteristics (age, gender, race, income), baseline co-morbidities, antipsychotic use and resource utilization and costs. Baseline co-morbidities were derived from the Clinical Classifications Software maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and QualityCitation34. Co-morbid conditions identified included anxiety disorders, heart disease, hypertension and alcohol-related disorders. Patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or episodic mood disorders were identified as having at least one medical claim with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM 295.xx) or episode mood disorder (296.xx) any time from 18 months before their index dates (continuous enrollment for the year before the beginning of the baseline period was not required) through their follow-up periods.

Baseline use of any typical or atypical antipsychotic was defined as at least one pharmacy claim for any typical or atypical antipsychotic. Baseline use of risperidone, olanzapine, ziprasidone or quetiapine was defined as at least one pharmacy claim for one of those specific antipsychotics. Baseline atypical antipsychotic switching, adherence and persistence were all based on the first observed atypical antipsychotic in the baseline period for patients who had any atypical antipsychotic use in the baseline period. Baseline switching was defined as at least one pharmacy claim for a different antipsychotic with no subsequent fills of the baseline antipsychotic during the baseline period. Baseline adherence to antipsychotic drug therapy was measured by a medication possession ratio (MPR; days’ supply of baseline antipsychotic during baseline ÷ number of days during baseline period). Baseline persistence was defined as the number of days from the first fill of the baseline antipsychotic through the run-out date of the last observed fill of the baseline antipsychotic before the index date; baseline atypical antipsychotic adherence, persistence and switching were set to 0.0 for patients who had no baseline atypical antipsychotic.

Psychiatric-related utilization and direct costs (in 2007 US dollars) were based on three sources: (1) medical claims with primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 290.xx-319.xx (); (2) outpatient pharmacy claims for oral atypical antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, anxiolytics and hypnotics or (3) CPT codes for psychiatric drug management (90862) or medical visits for therapy and evaluation (90804–90809, 90810–90815, 90816–90822, 90823–90829, 99510). Total healthcare costs were the sum of medical plus pharmacy costs. Healthcare costs during the follow-up period were derived from patient-paid and health plan-paid costs. The cost analyses are presented as the mean costs incurred by each patient over the 6-month period. Utilization outcomes included psychiatric-related inpatient facility admissions, emergency room visits and ambulatory visits (office visits, outpatient facility visits). [Codes and medications are available from the corresponding author.]

Table 1. ICD-9 codes used for the resource utilization and costs analysis.

Propensity score matching

Patients were assigned to treatment cohorts based on the index antipsychotic paliperidone ER, aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone or ziprasidone and matched using propensity score matching using a program available in Stata (version 9). Propensity scores were estimated with conditional logistic regressions incorporating therapy predictors as independent variables and cohort (e.g., paliperidone ER vs. another oral atypical antipsychotic) as the outcome. Patients in the paliperidone ER cohort were matched to patients in the other atypical antipsychotic cohorts in pairs (e.g., one regression-matched paliperidone ER and aripiprazole patients, another matched paliperidone ER and risperidone patients and so on) to obtain five pairs of 1:1 matched cohorts. Nearest-neighbor matching was employed, using age, gender, US census division, race, household income, baseline antipsychotic use (i.e., use of any traditional antipsychotic; use of non-index oral atypical antipsychotic; use of any antidepressant, mood stabilizer, anxiolytic or hypnotic), baseline oral atypical antipsychotic adherence and persistence, baseline switch between oral atypical antipsychotics, baseline co-morbid conditions, ≥1 primary schizophrenia diagnosis in 18 months before index date or 6-month follow-up period and baseline psychiatric-related utilization (number of psychiatric-related inpatient stays, emergency room visits and ambulatory visits).

Propensity score regression model fit was tested with Hosmer–Lemeshow and receiver operating characteristic statistics. After propensity score matching, comparisons of covariates and of baseline variables not used as covariates in the propensity score regressions (e.g., all-cause and psychiatric-related cost measures) were conducted between each of the five pairs of matched cohorts to confirm the comparability of cohorts. These comparisons were evaluated using paired t-tests to compare continuous covariates, and McNemar chi-square tests were used to compare categorical covariates. For each of the five propensity score regressions, the Hosmer–Lemeshow statistics showed good model fit, with p-values between 0.4142 and 1.000. The receiver operating characteristic statistics were also high for each model, indicating good model fit, with values between 0.7574 and 0.8170. Further, very few significant differences were seen between pairs of cohorts in the comparisons of covariates and other baseline variables (e.g., income of $30,000–49,999 between paliperidone ER vs. quetiapine and paliperidone ER vs. olanzapine; mean age between paliperidone ER vs. risperidone) that were not critical to the equitability of the cohort. Outcomes were compared between the propensity score–matched index antipsychotic cohorts. The outcomes for the paliperidone ER cohort were compared with those for each of the other cohorts using paired t-tests for continuous outcomes and McNemar chi-square tests for categorical outcomes.

Results

Patient demographics and characteristics

The study population comprised 562 patients. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age across the entire study population was 43.5 (13.9) years; 62.3% of patients were female and 76.9% of patients with non-missing values for race/ethnicity were Caucasian (). The majority of the patients came from the South Atlantic region (36.5%). One hundred patients (17.8%) had a primary schizophrenia diagnosis, and 425 (75.6%) had a primary episodic mood disorder diagnosis (data not shown). The most prevalent co-morbid conditions were anxiety (25.8%), heart disease (25.8%) and hypertension (21.7%) (). Additional data on baseline antipsychotic use, adherence and resource utilization are outlined in .

Table 2. Baseline patient demographics.

Table 3. Baseline clinical characteristics and resource utilization.

Psychiatric-related utilization and medical cost comparisons

Psychiatric-related resource utilization is shown in . The paliperidone ER cohort had fewer ambulatory visits, on average, than the risperidone cohort (4.6 [5.8] vs. 6.9 [10.1]; p = 0.05). There were no other significant differences in utilization.

Table 4. Psychiatric-related utilization outcomes: paliperidone ER cohort versus atypical antipsychotic cohorts.

Mean psychiatric-related medical costs (in 2007 US dollars) during the 6-month follow-up period ranged from $753 to $2,019 per patient (). Patients in the paliperidone ER cohort had significantly lower mean psychiatric-related medical costs ($753) than those in the olanzapine ($2,019; p = 0.01), quetiapine ($1,832; p = 0.03) and ziprasidone ($1,817; p = 0.01) cohorts. Mean psychiatric-related pharmacy costs ranged from $2,145 to $2,963. Mean pharmacy costs were significantly lower for the quetiapine ($2,145; p = 0.01) and risperidone ($2,250; p = 0.05) cohorts than for the paliperidone ER cohort (). Total psychiatric-related healthcare costs ranged from $3,510 to $4,800. Total costs were significantly lower for patients in the paliperidone ER ($3,510) cohort than for those in the ziprasidone ($4,559; p = 0.04) and olanzapine ($4,800; p = 0.02) cohorts ().

Table 5. Mean psychiatric-related costs per patient over 6 months.

Discussion

This exploratory study of pharmacy claims data compared psychiatric-related utilization and costs over 6 months among patients enrolled in a large national healthcare plan, who started treatment with oral atypical antipsychotics, specifically paliperidone ER, risperidone, aripiprazole, olanzapine, ziprasidone or quetiapine. With increasing emphasis on healthcare cost containment, resource utilization and cost analyses provide payers, formulary decision makers and other healthcare professionals with another drug selection parameter.

Psychiatric-related utilization in the paliperidone ER cohort was similar to that in other cohorts. However, mean psychiatric-related medical costs were significantly lower in the paliperidone ER cohort than in the olanzapine, quetiapine and ziprasidone cohorts. Further, overall psychiatric-related healthcare costs were significantly lower in the paliperidone ER cohort than in the olanzapine and ziprasidone cohorts.

Although various studies assessed atypical antipsychotic costs in the treatment of mental illnessesCitation35–42, few have included paliperidone ER (approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, December 2006). Edwards et al.Citation36 reported on the clinical and economic outcomes of oral atypical antipsychotics. The clinical outcomes with oral antipsychotics did not vary significantly. Economic outcomes, however, did vary; paliperidone ER was associated with savings in direct medical costs compared with risperidone, quetiapine, olanzapine, ziprasidone and aripiprazoleCitation36. Another cost-effectiveness study evaluated paliperidone ER, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, aripiprazole and ziprasidone in patients with schizophrenia for a 1-year period. Results suggested improved clinical outcomes and lower total healthcare costs with paliperidone ER than with other oral atypical antipsychoticsCitation42. These analyses differed from the current study in many aspects, making comparisons difficult. Interestingly, however, the modeling study by Edwards et al.Citation36 predicted paliperidone ER use could result in lower medical costs compared with the other oral atypical antipsychotics. The current study actually found lower medical costs associated with paliperidone ER treatment versus treatment with olanzapine, quetiapine and ziprasidone. However, future analyses with larger populations of patients observed for longer periods of time would be needed to confirm these findings.

Several limitations of the current study analysis must be noted. Given the exploratory nature of this analysis, no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons and multiplicity, and paired t-tests were used to determine statistical significance. Patients were required to have a minimum 60-day supply of medication, and it was not known whether patients took their medications as prescribed. Also, a patient's medication patterns before and after the index date were not identified or analyzed, as this analysis only examined resource utilization and costs 6 months after the index date. Sample medications provided by physicians are not identified in claims data. The data on race and income were from 2005, and 44–49% of these data were missing, which may have influenced the results. Additionally, because of the strict criteria of this analysis, the limited sample sizes and short post-index observation times (attributable to the launch of paliperidone ER in January 2007) and the inherent lag time with medical claims data, the study population was small and may have limited the generalizability of the findings. Because of the difficulty in tracking patients with mental illnesses over time, the primary diagnosis for this analysis was broadly defined; this may have created heterogeneity in the study design, limiting the ability to determine the mental conditions for which the medications were prescribed. Additional analyses should be performed to focus on comparing patients with the same primary diagnosis. Last, because the identification period was immediately after the launch of paliperidone ER in the US, the patients in the paliperidone ER cohort might have been switched to paliperidone ER after a treatment failure with another atypical antipsychotic. Patients initiated on paliperidone ER treatment shortly after product launch may have shared characteristics (e.g., more severe illness) that differed from those of patients initiated on paliperidone ER treatment at a later time, leading to concerns about selection bias. Nevertheless, the oral atypical antipsychotic cohorts were propensity score matched on use of baseline antipsychotics and antipsychotic therapy outcomes, mitigating the concerns about bias due to differences in baseline illness severity between patients in the paliperidone ER cohort and those in other cohorts.

Conclusion

The results from this exploratory analysis suggest that patients who initiated treatment with paliperidone ER may have psychiatric-related utilization costs comparable to those of patients using other oral atypical antipsychotics. Also, the paliperidone ER cohort may incur lower psychiatric-related costs than the olanzapine or ziprasidone cohorts. Future studies with larger sample sizes and longer study durations are needed to confirm these outcomes.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This analysis was supported by funding from Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, Titusville, NJ, USA.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

R.H. and F.C. have disclosed that they were contracted by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Services, LLC, to access and analyze the data. J.M.P. and R.D. have disclosed that they are employees of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and that they are Johnson & Johnson stockholders.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the writing and editing assistance provided by Matthew Grzywacz, PhD, Mariana Ovnic, PhD and ApotheCom in the development and submission of this manuscript.

References

- Keeping Care Complete: International Caregivers Survey. Woodbridge, VA: World Federation for Mental Health, 2006

- Sajatovic M. Bipolar disorder: disease burden. Am J Manag Care 2005;11:S80-84

- Lieberman JA, Perkins D, Belger A, et al. The early stages of schizophrenia: speculations on pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches. Biol Psychiatry 2001;50:884-897

- Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depress Anxiety 1998;7:3-14

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003;289:3095-3105

- McMorris BJ, Downs KE, Panish JM, et al. Workplace productivity, employment issues, and resource utilization in patients with bipolar I disorder. J Med Econ 2010;13:23-32

- Keeping Care Complete: International Psychiatrists Survey. Woodbridge, VA: World Federation for Mental Health, 2008

- Baillargeon J, Binswanger IA, Penn JV, et al. Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: the revolving prison door. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:103-109

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord 2003;73:123-131

- Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Grochocinski VJ, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals in a bipolar disorder case registry. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:120-125

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:1205-1215

- McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Soczynska JK, et al. Medical comorbidity in bipolar disorder: implications for functional outcomes and health service utilization. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:1140-1144

- Folsom DP, Hawthorne W, Lindamer L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:370-376

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:617-627

- Naismith SL, Longley WA, Scott EM, et al. Disability in major depression related to self-rated and objectively-measured cognitive deficits: a preliminary study. BMC Psychiatry 2007;7:32

- Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA 2003;289:3135-3144

- Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:1465-1475

- Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:1122-1129

- Begley CE, Annegers JF, Swann AC, et al. The lifetime cost of bipolar disorder in the US: an estimate for new cases in 1998. Pharmacoeconomics 2001;19:483-495

- Simpson GM. Atypical antipsychotics and the burden of disease. Am J Manag Care 2005;11:S235-241

- Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1-56

- Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT Jr, Kane JM, et al. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:441-449

- Lasser RA, Bossie CA, Gharabawi GM, et al. Remission in schizophrenia: results from a 1-year study of long-acting risperidone injection. Schizophr Res 2005;77:215-227

- Beasley CM Jr, Sutton VK, Hamilton SH, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine in the prevention of psychotic relapse. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23:582-594

- Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner R. A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2002;346:16-22

- Leucht S, Barnes TR, Kissling W, et al. Relapse prevention in schizophrenia with new-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1209-1222

- Pigott TA, Carson WH, Saha AR, et al. Aripiprazole for the prevention of relapse in stabilized patients with chronic schizophrenia: a placebo-controlled 26-week study. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:1048-1056

- Meltzer HY, Bobo WV, Nuamah IF, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of oral paliperidone extended-release tablets in the treatment of acute schizophrenia: pooled data from three 6-week, placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69:817-829

- Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, et al. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:31-41

- Lieberman JA, Hsiao JK. Interpreting the results of the CATIE study. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:139

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DR. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41-55

- Jing Y, Kim E, You M, et al. Healthcare costs associated with treatment of bipolar disorder using a mood stabilizer plus adjunctive aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine or ziprasidone. J Med Econ 2009;12:104-113

- Kim E, Maclean R, Ammerman D, et al. Time to psychiatric hospitalization in patients with bipolar disorder treated with a mood stabilizer and adjunctive atypical antipsychotics: a retrospective claims database analysis. Clin Ther 2009;31:836-848

- HCUP CCS. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). December 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp

- Vera-Llonch M, Delea TE, Richardson E, et al. Outcomes and costs of risperidone versus olanzapine in patients with chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders: a Markov model. Value Health 2004;7:569-584

- Edwards NC, Pesa J, Meletiche DM, et al. One-year clinical and economic consequences of oral atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:3341-3355

- Chen L, McCombs JS, Park J. The impact of atypical antipsychotic medications on the use of health care by patients with schizophrenia. Value Health 2008;11:34-43

- Bounthavong M, Okamoto MP. Decision analysis model evaluating the cost-effectiveness of risperidone, olanzapine and haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia. J Eval Clin Pract 2007;13:453-460

- Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries D, et al. A comparison of olanzapine and risperidone on the risk of psychiatric hospitalization in the naturalistic treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Ann Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;3:11

- Furiak NM, Ascher-Svanum H, Klein RW, et al. Cost-effectiveness model comparing olanzapine and other oral atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2009;7:4

- Barbui C, Lintas C, Percudani M. Head-to-head comparison of the costs of atypical antipsychotics: a systematic review. CNS Drugs 2005;19:935-950

- Geitona M, Kousoulakou H, Ollandezos M, et al. Costs and effects of paliperidone extended release compared with alternative oral antipsychotic agents in patients with schizophrenia in Greece: a cost effectiveness study. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2008;7:16