Abstract

Objective:

Medication adherence in chronic diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS) plays an important role in predicting long-term outcomes, yet existing data on adherence in employee populations are not found. The objective of this study is to compare adherence among employees treated with disease modifying treatments (DMTs) for MS in the year following treatment initiation.

Methods:

A healthcare claims database of US employees from 2001 to 2008 was used to identify patients with MS based on two or more DMT prescriptions or one DMT prescription with an MS diagnosis (ICD-9 340.xx). Employees continuously employed and with health plan coverage for 1 year following DMT initiation were eligible. Two measures were used in estimating adherence after DMT initiation: (1) persistence (the number of days from DMT initiation to the first 30-day gap in supply) and, (2) annual compliance, assessed by the medication possession ratio (MPR = number of days with a medication supply in the year divided by 365 days). Wilcoxon tests on time-to-event data and t-tests were used to compare persistence and MPR, respectively, between DMT groups. Other measures of resource utilization were also compared.

Results:

Overall, 358 employees [179 interferon [IFN]-β1a-IM (Avonex = ‘A’); 63 IFN-β1b (Betaseron = ‘B’); 20 IFN-β1a-SC (Rebif = ‘R’); 96 glatiramer acetate (Copaxone = ‘C’)] were eligible for analysis. No significant differences in age, gender, and certain job-related variables existed between cohorts. Persistence was better for ‘A’ than ‘B’ (p = 0.039), ‘C’ (p = 0.0007), and ‘R’ (p = 0.130). At 1 year, a greater proportion of ‘A’ employees were persistent (60.34%) than ‘B’ (42.86%, p = 0.016), ‘C’ (42.71%, p = 0.0052), and ‘R’ (45.00%, p = 0.190). ‘A’ also had the highest MPR (0.782) which was significantly higher than ‘C’ (MPR = 0.698, p = 0.0160) and statistically equivalent to ‘B’ (MPR = 0.705, p = 0.0576) and ‘R’ (MPR = 0.761, p = 0.7347).

* Avonex is a registered trade name of Biogen Idec Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA, USA.

† Betaseron is a registered trademark of Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc., West Haven, CT, USA.

‡ Rebif is a registered trademark of EMD Serono, Inc. Rockland, MA, USA and its affiliates.

§ Copaxone is a registered trademark of Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Petach Tikva, Israel.

Limitations:

The study has limitations characteristic of administrative claims database studies and small sample sizes. The population may not be representative of undiagnosed/untreated MS patients, those not able to maintain employment, and those not using the initial therapy.

Conclusions/relevance:

Among employees treated with ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’, and ‘R’ for MS, ‘A’ patients had significantly greater medication adherence.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory auto-immune disorder characterized by disseminated areas of demyelination and scarring in the brain and spinal cordCitation1. MS is one of the most common diseases of the central nervous systemCitation2 affecting about 2.5 million persons worldwide and from 350,000 to 500,000 in the United StatesCitation3,Citation4. The cause of MS is unknown. Diagnosis usually occurs in younger adults between the ages of 20 and 50 yearsCitation4, and women are 50% more likely to be affected than menCitation2.

MS can be treated but not cured. Treatment goals include reducing inflammation, shortening acute exacerbations, decreasing the frequency of exacerbations, relieving symptoms, and slowing the progression of both physical and cognitive disabilityCitation1,Citation5.

The use of disease modifying treatments (DMTs) is considered first-line therapy and aims to reduce the frequency and severity of relapses, and delay disease progressionCitation1,Citation5. The objective of this study is to compare adherence among DMTs within an employed MS population in the year following treatment initiation.

All DMTs are self-administered parenterally (subcutaneously [SC] or intramuscularly [IM]) by the patient and are given daily to once weekly depending on the product. Available DMTs include: interferons (IFNs) such as IFN-β1a IM (Avonex = ‘A’)Citation6, IFN-β1b (Betaseron = ‘B’)Citation7, and IFN-β1a SC (Rebif = ‘R’)Citation8 and an L-glutamic acid polymer with L-alanine, L-lysine and L-tyrosine, acetate (salt) glatiramer acetate (Copaxone = ‘C’)Citation9 (See Overview of available DMTs).

Table 1. Overview of disease modifying treatments (DMTs) for multiple sclerosis.

Medication adherence in chronic diseases like multiple sclerosis is a key factor in predicting long-term outcomes. For the patient, adherence reflects an active decision process and involves several factors: (1) acceptance – readiness to accept the diagnosis and willingness to receive treatment, (2) persistence – the motivation to continue treatment long-term, and (3) compliance – the ability and willingness to follow the prescribed regimenCitation10,Citation11. Often non-compliant patients choose to facilitate daily life or minimize adverse effects by foregoing treatmentCitation11. Guidelines from the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) and other studies have suggested that prescriptions fills are adequate measures of medication useCitation12–14.

Adherence rates found in the literature vary widely due to differences in definitions and the measures of adherence usedCitation15. Adherence rates in patients receiving DMTs range mostly from 60 to 76% over treatment periods of 2–5 years and resemble those of other chronic disease states such as diabetes and heart failureCitation10. The majority of patients who discontinue treatment with DMTs do so within the first 2 yearsCitation10,Citation16.

Several studies have reported the reasons for non-adherence to DMTs. A recent global survey of MS patients reported that ‘forgetting to administer’ was the most common reason for non-adherence followed by ‘tired of taking injections’. Other reported reasons for non-adherence are ‘perceived lack of efficacy’ and ‘adverse effectsCitation17,Citation18.’

Data on medication adherence with disease modifying treatments (DMTs) have been published for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS), however, limited comparative data are availableCitation19,Citation20. Most available data are based on non-comparative clinical studiesCitation16,Citation21,Citation22, chart reviewsCitation23 and surveysCitation24,Citation25.

Methods

Data for this retrospective analysis was taken from the Human Capital Management Services Research Reference Database, which is fully de-identified and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) compliantCitation26. The database contains demographics, payroll, healthcare (including prescription drugs), disability, absence and workers’ compensation information for a population of over 670,000 employees and their covered dependents. The data was compiled from several large national US employers in retail, service, manufacturing, and financial industries and has been used in prior research, including research in MSCitation27. For all subjects, healthcare was provided through managed-care plans contracted by respective employers.

Employees with a diagnosis of MS were identified from medical and drug claims by any primary, secondary, or tertiary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) diagnostic code for MS (340.xx) between January 1, 2001 and June 30, 2008 and by a prescription for a DMT, or two or more DMT prescriptions without an ICD-9 diagnosis. Employees without a DMT prescription were not included. MS employees with DMT prescriptions were assigned to the ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘R’ cohorts based on the first type of therapy received, thus creating four mutually exclusive cohorts (one for each DMT). Employees taking natalizumab (Tysabri, Biogen Idec and Elan Pharmaceuticals) were not included due to sample size limitations.

Index dates were defined as the date of the patient's first DMT prescription. Patients were excluded from the study if they received more than one type of DMT during the 12 months after their index date (n = 141) in order to allow clean comparisons between cohorts of the association between use of each DMT and outcomes. Also, patients were excluded who did not have health insurance enrollment for the entire 12 months after their index date (n = 189).

Outcome measures

Three measures were used in estimating adherence after DMT initiation: (1) persistence, defined as the number of days from DMT initiation to the first 30-day gap in supply; (2) the distribution of annual medication supply, defined as the percent of each study cohort with 1, 2, 3, … , or 12 months supply of medication; and lastly, (3) annual compliance, as measured by the Medication Possession Ratio (MPR), defined as the number of days the employee had a supply of medication during the year following DMT initiation divided by the number of days in the yearCitation12 – that is, the total number of days with medication supply available in the year divided by 365.

For each DMT the following outcomes were also calculated: MS-specific medical costs (paid amounts from medical insurance claims with primary ICD-9 codes for MS), MS-specific prescription drug costs (paid amounts for the particular DMT), comorbid conditions (e.g., non-MS-specific) medical costs, non-MS-specific prescription drug costs, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)Citation28, percent of employees using specific therapies (adrenal cortical steroids, medications for overactive bladder, and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), and the percent of patients with inpatient hospital services. All outcomes were calculated during the 12 months after each subject's index date. The percent of patients with inpatient hospital services was calculated among only those subjects from health plans providing data which specify the place of service where care was provided.

Statistical analysis

Because of the similarity between cohorts in age, gender, race, salary, and other variables, no matching or regression control was required. The mean values for continuous demographic data and MPRs were calculated and compared using t-tests. Discrete demographic variables and distributions of the medication supply by months were compared using chi-square (χCitation2) tests. Persistence was compared using Wilcoxon tests on time-to-event data, where the event of interest was the beginning of the first 30-day gap in medication supply. All costs are inflation-adjusted to July 2008 US dollars. Throughout the study, results are significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

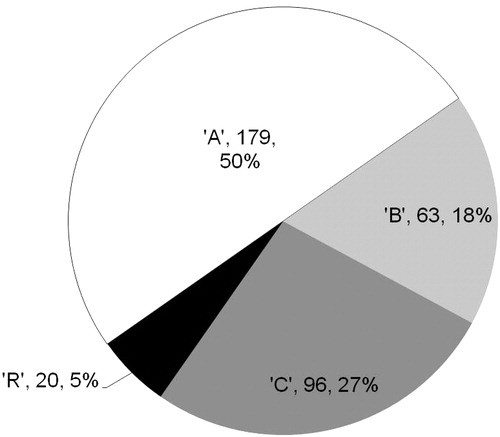

Overall, 358 employees were eligible for analysis, with half of those subjects using ‘A’ (). No significant differences in age, gender, race, salary, exempt status, or full-time/part-time status existed between cohorts (). There were statistically significant differences in tenure (length of time employed by their current employer), with the employees using ‘C’ and ‘R’ having less tenure than employees using ‘A’. Also, the ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘R’ cohorts were statistically significantly less likely to be single than the ‘A’ cohort.

Figure 1. Disease modifying treatments (DMT) used for multiple sclerosis within the 358 employee study population.

Table 2. Demographics of study cohorts by disease modifying treatments.

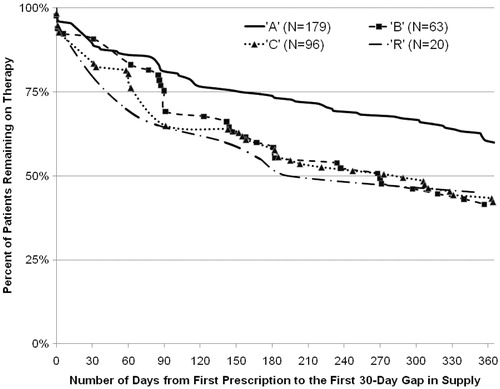

Persistence () was significantly better for ‘A’ than ‘B’ (p = 0.039) and ‘C’ (p = 0.0007) and non-significantly better than ‘R’ (p = 0.13). At 1-year, a greater proportion of ‘A’ employees were persistent (60.34%) compared with those receiving ‘B’ (42.86%, p = 0.016), ‘C’ (42.71%, p = 0.0052), or ‘R’ (45.00%, p = 0.19).

Figure 2. Medication persistence with disease modifying treatments (DMT) for persons with multiple sclerosis.

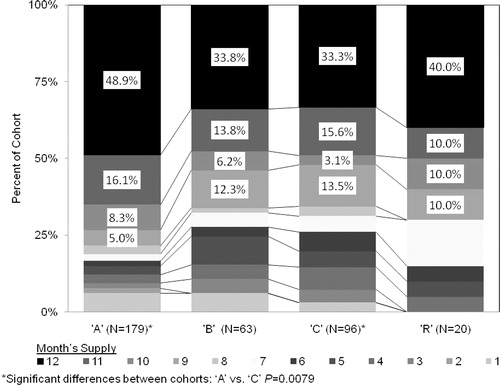

The ‘A’ cohort was most likely to have the highest number of months’ supply, with almost 50% of patients having a full year (12 months) of treatment (). Compliance, based on the MPR () was highest for ‘A’. The ‘A’ MPR of 0.782 represents approximately a 285-day supply of medication and was significantly higher than that for ‘C’ by 0.084 (30.7 more days supplied) and non-statistically significantly higher than ‘B’ and ‘R’ by 0.077 (28.1 days) and 0.021 (7.7 days), respectively.

Figure 3. Percent of study cohorts by number of months supply of disease modifying treatments for multiple sclerosis.

Table 3. Comparative data by disease modifying treatments.

The persistence, MPR, and months supply of the combined group of ‘B’, ‘C’, and ‘R’ users (BCR) were calculated and compared with ‘A’. The ‘A’ cohort's persistence (median > 365 days) was significantly longer than that of BCR (median 281 days, p < 0.0001); the MPR for BCR (0.707) was significantly lower than the MPR for the ‘A’ (0.782, p = 0.010); and 81.6% of the ‘A’ population had at least 8 months of medication, compared with 69.3% for BCR (p = 0.0069).

Additional analysis

Other comparative data () found MS Drug costs for the ‘R’ cohort were 27–33% greater than for the other therapy cohorts (p < 0.001 for each comparison), and MS disease-specific medical costs were 1.4 to 2.1 times higher for employees on ‘C’ than all other therapies (p > 0.05 for each comparison). While the non-MS drug costs were nearly all similar (‘A’ = $1,334, ‘B’ = $1,351, ‘C’ = $1,999 [p = 0.033 vs. ‘A’], and ‘R’ = $1,163), the mean non-MS (other conditions) medical costs for ‘R’ ($8,936) were 3.4 to 4.7 times greater (p > 0.05 for each comparison) than that of all of the other agents (‘A’ = $2,600; ‘B’ = $1,902; and ‘C’ = $2,305).

Discussion

A patient's medication acceptance, persistence and compliance are important in order to obtain the full benefits of DMTs. Persistence at 12 months and adherence to treatment, as measured by MPR, were greatest for patients treated with ‘A’ in this retrospective comparative study.

To ensure the comparability of the cohorts, this study excluded subjects who used a second DMT during the 12 months following their initial use. An examination of all employees that initiated therapy found that the percentages of employees who were excluded due to second DMT (those who may have switched) during the 12 months following their initial use, were 17% for ‘A’, 25% for ‘B’, 38% for ‘C’, and 68% for ‘R’. All pair-wise comparisons between these percentages are statistically significant (p < 0.02).

Findings of lower discontinuation rates in ‘A’ users are supported in the literature. In a recent study, significantly more patients remained on ‘A’ over the 1-year trial period (86.6 vs. 79.7% for ‘B’, 60.9% for ‘C’, and 83.2% for ‘R’ [overall p = 0.0364]) than any other treatmentCitation19. A small telephone survey of patients using DMTs found that the rate of discontinuation ranged (without significant differences) from 28.2% for ‘C’ (mean length of use pre-discontinuation: 9.14 months) to 34.4% for ‘A’ (mean 19.2) to 40.5% for ‘B’ (mean 22.3 months); ‘R’ was commercially unavailable at the timeCitation24.

Additionally, ‘A’ was different than the other three DMTs when they were viewed together (as a combined BCR). In fact, persistence with ‘B’, ‘C’, and ‘R’ seemed to converge with each other and diverge from the persistence of ‘A’ at about 90 days. Median persistence for ‘A’ was more than 365 days, but for BCR, the median was only 281 days (p < 0.0001).

Similarly, Reynolds et al.Citation20 found that ‘A’ users’ time to discontinuation, the ‘complement’ of persistence, was significantly greater than ‘B’, and non-significantly greater than ‘R’ and ‘C’. Reynolds also found that at 6, 12, and 18 months, the prevalent use of ‘A’ was significantly higher than ‘B’, and non-significantly higher than ‘C’ and ‘R’Citation20.

As in the current study, Reynolds also found that MPR was highest for ‘A’. Specifically, the ‘A’ MPR was significantly higher than that of ‘B’, ‘C’, and ‘R’ 1–6 months after start of index treatment, significantly higher than the MPR of ‘B’ and ‘C’ 7 to 12 months after, and significantly higher than the MPR of ‘C’ 12–18 months after the start of the index treatmentCitation20.

In the current study, the ‘R’ cohort's MS drug costs were significantly higher than the other DMTs. Given the longer duration and higher MPR for ‘A’ compared to the other agents, it is not surprising that the ‘A’ cohort's costs were non-significantly higher than ‘B’ and ‘C’. In the Reynolds study the MS drug costs were significantly higher in all groups compared to ‘A’ usersCitation20. The non-MS drug costs were significantly higher for the ‘C’ users than the ‘A’ users, and the other between-group comparisons were all non-significant.

Multiple analyses of compliance and persistence have shown that adherence to DMTs can be positively influenced by increased and ongoing support from the healthcare team, addressing among others, injection-related issues such as adverse reactions, administration difficulties, and injection frequencyCitation10,Citation29. Injection site reactions (ISR) are one of the most common adverse events leading to treatment discontinuationCitation10. Recently released findings show that at the first assessment, significantly fewer ‘A’ patients experienced ISRs (13.4 vs. 57.7% for ‘B’ [p < 0.0001], 30.4% for ‘C’ [p = 0.056], 67.9% for ‘R’ [p < 0.001]), necrosis (0.0 vs. 5.7% for ‘B’ [p = 0.0279], 0.0% for ‘C’ [p = NS], 6.0% for ‘R’ [p = 0.0201]) and lipoatrophy (1.2 vs. 8.9% for ‘B’ [p = 0.0210], 13.0% for ‘C’ [p = 0.0322], 10.3% for ‘R’ [p = 0.0093])Citation19. Additionally, no ‘A’ patients missed a dose in the 4 weeks prior to the first assessment due to ISRs (vs. 5.7% for ‘B’ [p = 0.044], 4.3% for ‘C’ [p = NS], and 7.1% for ‘R’ [p = 0.011]).

Evidence across multiple chronic disease states suggests that simpler regimens result in greater adherence. Studies have shown that single daily doses are better than multiple daily doses and that once weekly dosing results in significantly better compliance than daily dosingCitation30,Citation31. All three results of the current study would support this finding with once weekly ‘A’ preferred over other multi weekly DMTs. Similarly, Tremlett and Oger'sCitation23 comparative survey of 798 respondents treated with DMTs, found that patients treated with ‘A’ were significantly less likely to miss any injections in the last 4 weeks (21%) compared to patients treated with ‘R’ (32%; p = 0.0172), ‘B’ (51%; p < 0.0001) or ‘C’ (51%; p < 0.0001)Citation23.

The current study has revealed additional employment-related findings which may warrant further investigation in the future. The mean tenure for all cohorts ranged from 6.1 to 9.8 years, and suggests that some accommodations may have been made by their employers, or alternatively, these subjects might be among the 15–30% of subjects able to maintain employmentCitation32,Citation33. Only 90% of the ‘R’ cohort was employed full-time while over 96% of the other DMT cohorts’ employees were full-time.

Across all DMTs, the use of cortical steroids was over 40%. ‘R’ patients were also the most likely to have an inpatient hospitalization (15%), compared with ‘A’ (8%), ‘B’ (6%), and ‘C’ (5%), although the differences among DMTs were not statistically significant. Whether these findings are linked to the overall effectiveness of individual DMTs remains to be determined. However, the likelihoods of inpatient hospitalizations found in this study are not inconsistent with recent ‘real-world’ studies which found ‘A’ patients have the least number of inpatient hospitalizations and ER visits over follow-up compared to ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘R’ patientsCitation34.

Unlike some of the models based on clinical trial data, this real-world observational study compared all four available DMTs and allowed for interesting insights into the treatment of MS in managed-care populations of employees. This study also suggests areas of research such as dosing frequency, ease of administration, and modes of medication delivery that can be pursued to improve therapy effectiveness by increasing treatment adherence in patients with MS.

Limitations

While this study adds to the body of evidence about persistence and compliance among employees with MS treated with DMTs, it has the same limitations characteristic of database studies using administrative claims. For example the availability of MS severity classification and MS stage or type would have allowed the study to control for a potential source of bias between cohorts. In addition, this population may not be representative of MS patients who have not been diagnosed or treated, those treated with other therapies, or those not able to maintain employment. Had these kinds of patients been treated with DMTs and included in the study, their outcomes may have been different than the outcomes found herein. Additionally, because the study focused on adherence and persistence with the initial therapy, further research may be warranted on the events after product discontinuation. Furthermore, the small sample size suggests that results may be interpreted with caution. For example, while the persistence was not significantly different between ‘A’ and ‘R’ (p = 0.1288) in the current study, this may be attributable to the small ‘R’ sample size (n = 20) and low power. Observationally, the graph in shows the ‘R’ line to be lower than all other agents until about day 300 (10 months), at which point it is still lower than the ‘A’ line and clustered around the ‘B’ and ‘C’ therapies.

Given that four cohorts were compared, adjustment of p-values for multiple testing may deserve consideration, however, when this was attempted for the MPR outcomes, it was not clear that such an adjustment would alter the qualitative results. The Dunnett t-testCitation35 for comparing the MPR of ‘B’, ‘C’, and ‘R’ to that of ‘A’ with a multiple testing adjustment found that MPR values of ‘A’ and ‘C’ were significantly different (p < 0.05). On the other hand, when ‘A’ was compared with the combined group of ‘B’, ‘C’, and ‘R’ users as described above, this ‘two-cohort’ MPR comparison was statistically significant and would not be affected by the multiple comparison phenomenon. Additionally, the present study finding that the ‘A’ cohort performed as well or better than the other cohorts in all three adherence metrics (MPR, persistence, and months supplied) is an indication that adjustments for multiple testing would not qualitatively change the conclusions of the study.

Despite limitations, the study cohorts had no significant differences in age, gender, and certain job-related variables, and thus, the study represents an important addition to the literature, corroborating and adding to prior studiesCitation19,Citation20,Citation23 that also indicated significantly better adherence results for ‘A’.

Conclusions

Among employees treated with ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’ or ‘R’ for MS, ‘A’ patients had significantly greater medication adherence. The potential for realizing the full clinical benefit of DMT treatment depends considerably on patient compliance and persistence. Future research is needed to determine the impact of adherence on patient outcomes, costs and productivity.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Financial support for this study was provided by Biogen Idec, Inc, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

N.L.K. and I.A.B. have disclosed that they are employed by HCMS Group, a company that received funding from Biogen Idec to conduct this research. K.R. has disclosed that she is employed by Biogen Idec. R.A.B. has disclosed that he is an employee of the JeSTARx Group, a company that received funding from Biogen Idec for its role in this research.

Acknowledgments

For assistance with reviews of the data and drafts of this manuscript, the authors would like to thank James E. Smeeding, RPh, MBA, President of the JeSTARx Group, and Harold H. Gardner, MD, President of HCMS for their contributions. The authors would also like to acknowledge Conny Burkett, RPh, Partner, Paradigm Consulting, Inc., for assistance with the editing and summarization of the clinical aspects of the different therapies.

Notes

* Avonex is a registered trade name of Biogen Idec Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA, USA.

† Betaseron is a registered trademark of Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc., West Haven, CT, USA.

‡ Rebif is a registered trademark of EMD Serono, Inc. Rockland, MA, USA and its affiliates.

§ Copaxone is a registered trademark of Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Petach Tikva, Israel.

* Avonex is a registered trade name of Biogen Idec Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA, USA.

† Betaseron is a registered trademark of Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc., West Haven, CT, USA.

‡ Rebif is a registered trademark of EMD Serono, Inc. Rockland, MA, USA and its affiliates.

§ Copaxone is a registered trademark of Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Petach Tikva, Israel.

References

- Porter R & Kaplan J, editors. Merck Manual online: Multiple Sclerosis. Available at http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec16/ch222/ch222b.html. Accessed October 21, 2009

- Multiple Sclerosis International Federation: Epidemiology. Available at http://www.msif.org/en/. Accessed October 21, 2009

- Joy JE, Johnston RB, eds. Multiple Sclerosis: Current Status and Strategies for the Future Committee on Multiple Sclerosis. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2004. Available in part at: http://books.nap.edu/execsumm_pdf/10031.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2008

- Multiple Sclerosis Foundation: Epidemiology. Available at http://www.msfocus.org/who-gets-multiple-sclerosis.aspx. Accessed October 21, 2009

- Miller JR. The importance of early diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Pharm 2004;10(Suppl B):S4-11

- Avonex PI. Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/ucm086060.pdf. Accessed May 26 2010

- Betaseron PI. Available at http://berlex.bayerhealthcare.com/html/products/pi/Betaseron_PI.pdf?WT.mc_id=www.berlex.com. Accessed September 23 2009

- Rebif PI. Available at http://www.mslifelines.com/_assets/pdf/Rebif_PI.pdf?source=external. Accessed September 23 2009

- Copaxone PI. Available at http://www.copaxone.com/pdf/prescribinginformation.pdf. Accessed September 23 2009

- Costello K, Kennedy P, Scanzillo J. Recognizing nonadherence in patients with multiple sclerosis and maintaining treatment adherence in the long term. Medscape J Med 2008;10:225. Epub 2008 September 30

- Cohen BA. Adherence to disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2006;Suppl:32-37

- Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA, et al. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health 2007;10:3-12

- Steiner J, Prochazka A. The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: methods, validity, and applications. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:105-116

- Choo P, Rand C, Inui T, et al. Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records, and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to anti-hypertensive therapy. Med Care 1999;37:846-857

- Klauer T, Zettl UK. Compliance, adherence, and the treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2008;255(Suppl 6):87-92

- Lafata JE, Cerghet M, Dobie E, et al. Measuring adherence and persistence to disease-modifying agents among patients with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2008;48:752-757

- Portaccio E, Zipoli V, Siracusa G, et al. Long-term adherence to interferon beta therapy in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol 2008;59:131-135. Epub 2007 November 30

- Ross AP. Tolerability, adherence, and patient outcomes. Neurology 2008;71:S21-23

- Beer K, Muller M, Hew-Winzeler A, et al. An evaluation of adverse skin reactions in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2009;15:S238-239

- Reynolds MW, Stephen R, Seaman C, et al. Persistence and adherence to disease modifying drugs among patients with multiple sclerosis. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:663-674

- Fraser C, Morgante L, Hadjimichael O, et al. A prospective study of adherence to glatiramer acetate in individuals with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs 2004;36:120-129

- Río J, Porcel J, Téllez N, et al. Factors related with treatment adherence to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2005;11:306-309

- Tremlett HL, Oger J. Interrupted therapy. Stopping and switching of the β-interferons prescribed for MS. Neurology 2003;61:551-554

- Daugherty KK, Butler JS, Mattingly M, et al. Factors leading patients to discontinue multiple sclerosis therapies. J Am Pharm Assoc 2003;45:371-375

- Turner AP, Williams RM, Sloan AP, et al. Injection anxiety remains a long-term barrier to medication adherence in multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol 2009;54:116-121

- The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Fact Sheet. U.S. Department of Labor, Employee Benefits Security Administration, December 2004. Available at http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/newsroom/fshipaa.html. Accessed February 29 2008

- Brook RA, Rajagopalan K, Kleinman NL, et al. Absenteeism and health benefit costs among employees with multiple sclerosis. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:1469-1476

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-383

- Devonshire V, Cassidy DD, Popelar L. Adherence to disease-modifying therapy—recognizing barriers and offering solutions: a roundtable discussion. In: Ross AP, Editor in MS Counseling Points. Ridgewood, NJ: Delaware Media Group, LLC, 2007:3:1-12. Available at http://www.iomsn.org/pdf/CPMS0702.final.pdf. Accessed May 26 2010

- Saini SD, Schoenfeld P, Kaulback K, et al. Effect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseases. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:e22-33

- Cramer JA, Lynch NO, Gaudin AF, et al. The effect of dosing frequency on compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy in postmenopausal women: a comparison of studies in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. Clin Ther 2006;28:1686-1694

- Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, et al. The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study: methods and sample characteristics. Mult Scler 2006;12:24-38

- Vogenberg FR, Holland JP, Liebeskind D. Employer benefit design considerations for the era of biotech drugs. J Occup Environ Med 2007;49:626-632

- Stephenson JJ, Kamat SA, Cai Q, et al. Economic impact of disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis patients in a managed care setting. Value Health 2009;12:A192

- SAS Institute Inc., SAS/STAT 9.2 User's Guide, Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2008