Abstract

Objective:

This analysis was to assess the long-term clinical and economic implications of galantamine in the treatment of mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease (AD) in Germany.

Methods:

An economic model was developed using discrete event simulation to predict the course of AD through changes in cognition, behavioural disturbance, and function over time. It compares the costs and benefits of galantamine versus no-drug treatment and ginkgo biloba. Clinical data were mainly derived from analyses of pooled data from clinical trials. Epidemiological and cost data were obtained from literature and public data sources. Costs (2009 euros) from the perspective of the German Statutory Health Insurance were used.

Results:

The mean survival time for the model population is about 3.44 years over 10 years of simulation. Galantamine delays average time to severe stage of the disease by 3.57 and 3.36 months, compared to no-drug treatment and ginkgo biloba, respectively. Galantamine reduces time spent in an institution by 2.34 and 2.21 months versus no-drug treatment and ginkgo biloba, respectively. The use of galantamine is projected to yield net savings of €3,978 and €3,972 per patient versus no-drug and ginkgo biloba treatments. These results, however, may be limited by lack of long-term comparative efficacy data as well as data on long-term care costs based on multiple outcome measures.

Conclusion:

Compared to no-drug treatment and ginkgo biloba, galantamine therapy provides clinical benefits and achieves savings in healthcare costs associated with care for patients with mild-to-moderate AD in Germany.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder. The progression of the disease is characterised by worsening of cognition, impairment of functional ability to perform activities of daily living, and neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as mood swings, apathy, psychosis, and agitationCitation1. In the late stages of the disease, patients lose their capacity to perform the basic activities of daily living and progressing to the inevitable need for full-time care (FTC).

Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia worldwide, accounting for up to 75%, or 26 million, of patients with dementia globallyCitation2. An estimated 1 million people in Germany suffer from dementia, 65% of whom have ADCitation3. Age is the primary risk factor for the diseaseCitation4. The prevalence of AD rises with increasing age. While the disease affects 1% of 60-year-olds, its prevalence rises sharply to 30% among 85-year-oldsCitation1. With the increase in life expectancy and continued growth in both the absolute numbers and the proportion of the elderly, the prevalence of AD in Germany is expected to rise in the coming decades. To cope with this serious public health issue, the German Federal Government has included dementia as a main topic in the National Social Report on the Elderly issued by the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women, and Youth. The Bundesministerium für Gesundheit believes that despite economic pressures, it is possible for people with dementia to enjoy a decent life and obtain the best possible medical and nursing care. Therefore, the ‘Leuchtturmprojekt Demenz’, with a budget of €13 million, was initiated in 2008 to improve the evidence-based medical and care service provision for patients with dementiaCitation5.

The burden of AD is substantial for patients, their caregivers, and society itself. The annual worldwide total societal cost of treating approximately 34.4 million patients with dementia was estimated to be US$422 billion in 2009, with direct costs accounting for US$279 billion and the costs of informal care amounting to US$142 billionCitation6. As caregivers play a significant role in caring for patients with AD, the caregiver burden in AD is substantial as borne out by these data, which show informal care represents 34% of the total cost of care. The economic burden of dementia in Europe has been estimated at €55–66 billion (2003 values) annuallyCitation7. The estimated annual cost of treating AD (including both the formal and informal care) in Northern and Western Europe is €21,000 per patient. Updated cost data for AD in Germany is not available. However, a 1998 study estimated the mean annual per patient total cost of care (formal and informal) for AD in Germany to be €12,040 (1998 values)Citation7.

Current pharmacological agents used for managing symptoms of AD consist of cholinesterase inhibitors for mild-to-moderate disease and memantine for moderately severe to severe diseaseCitation8. Galantamine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, which is commonly prescribed has beneficial effects on the cognitive, functional, and behavioural symptoms in patients with mild-to-moderate AD and is well-toleratedCitation9,Citation10. These clinical benefits were confirmed in a recent assessment conducted by the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG)Citation11,Citation12. In addition, galantamine reduces caregiver burden and delays time to placement in a nursing homeCitation13,Citation14. The Assessment of Health Economics in Alzheimer's Disease (AHEAD) model is an individual Markov process model that conceptualises the disease progression in terms of need for FTC. Over the past decade, the model has been used to assess the cost effectiveness of galantamine in the treatment of AD in many countries except in GermanyCitation15–20. All of these assessments consistently indicated that galantamine delays time to FTC and contributes to overall cost savings.

Despite a large body of evidence to support the use of galantamine, there are concerns regarding the overall benefits of treatment with galantamine and other cholinesterase inhibitors. This is evident from the recent reimbursement policy issued by the German Federal Joint Committee (G-BA), stating that in order for cholinesterase inhibitors to be reimbursed under the German Statutory Health Care System, patients treated with these agents must be evaluated by their treating physicians every 6 months to ensure that they continue benefiting from the treatmentCitation21. Due to these concerns, a new economic model assessing the long-term clinical and economic implications of galantamine in the treatment of mild-to-moderate AD was developed to facilitate the ongoing assessment by the IQWiGCitation22. Instead of adopting the widely used AHEAD model, this new model was developed to incorporate newer data regarding disease progression and to conform to the updated IQWiG guidelines for cost-benefit assessmentCitation23. The objectives of the present paper are to provide the detailed information regarding the model and report the results of the cost-benefit assessment of galantamine in the treatment of mild-to-moderate AD in Germany.

Patients and methods

Model

The model was created to perform economic analyses from the perspective of the community of citizens insured by the German Statutory Health Insurance (SHI), as recommended by the IQWiG guidelinesCitation23. Discrete event simulation (DES)Citation24, an individual-patient simulation that conceptualises the progressive course of a disease and its management in terms of events that occur over time, was chosen for this model mainly due to its advantage of ‘memory’ that remembers every past event experienced by each individual patient throughout the course of the model and continuously updates the patient's history. This allowed the model to track relevant information regarding events experienced by a patient over the course of simulation. The model then used the information to predict the subsequent course of the disease. The other advantage of the DES model is its capability in explicit handling of the passage of time in a continuous mode rather than in a discrete scale. These advantages permit a more realistic, efficient modelling of disease progression over time based on patient characteristics and other relevant information with fewer unrealistic assumptions or oversimplifications of the course of the disease.

Model concept

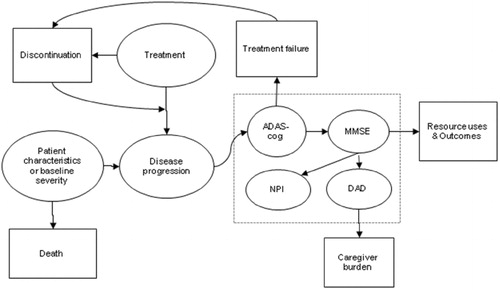

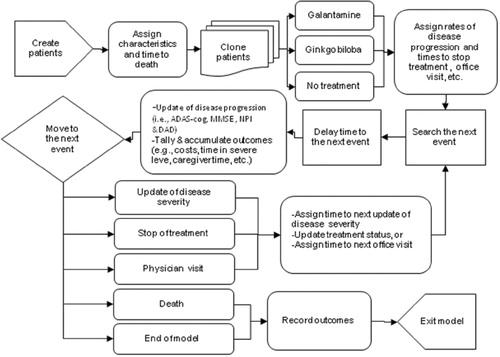

A snapshot of the model structure with key model parameters and outcomes as well as their inter-relationships is displayed in . Disease progression is influenced by baseline disease severity and treatment received and was modelled through three domains: cognition, using both the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive scale (ADAS-cog) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE); behaviour, using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) scale; and activities of daily living, using the Disability Assessment for Dementia (DAD) scale. In the present model, both ADAS-cog and MMSE scales were used for modelling the decline in cognition. This is because the source clinical trials with galantamine used ADAS-cog as the only scale for measuring cognitionCitation9,Citation10. Additionally, the prediction of rates of change in NPI and DAD scores as well as other outcomes of interest was done using the MMSE scale based on the availability of data from published literature. Therefore, ADAS-cog scores were converted into MMSE scores using a published equation throughout the simulationCitation26. The model also considered the impact of non-persistence with treatment on disease progression. Non-persistence could be initiated by patients due to any cause or by physicians due to treatment failure, defined as progression to severe stage of the disease (i.e., ADAS-cog >47). The model also measured the amount of time spent by caregivers, which is conditional on patient's DAD scores. Finally, survival time in this model was predicted based on patient's age at baseline and gender, independent of treatment and disease progression.

Model flow

A simplified schematic representation of how patients were simulated from the start to the end is displayed in . At the beginning of the simulation, 1,000 patients were created by sampling from a library of actual patient profiles obtained from two galantamine clinical trialsCitation9,Citation10. Each patient profile included a set of patient characteristics such as age, gender and baseline ADAS-cog, NPI and DAD scores. Based on each patient's age at baseline and gender, time to death was estimated and assigned to the patient. Then two identical clones of each simulated patient were created. One ‘clone’ was assigned to receive no-drug treatment, one to receive galantamine 16 or 24 mg per day, and the third clone to receive ginkgo biloba 240 mg per day. Ginkgo biloba at this dose was selected as the only pharmacological comparator in this model because it is the only treatment that receives continued coverage without the requirement for periodical evaluation under the G-BA reimbursement policy. In addition, beneficial clinical effect of ginkgo biloba was demonstrated only on a daily dose of 240 mg compared to placebo in the recent IQWiG assessmentCitation27. The cloning step simulated ideal randomisation. Duplicating patients before the treatment step ensured that variances other than the assigned treatment were not present. After cloning, the rate of disease progression and time to other relevant events, including treatment discontinuations and routine office visits, were assigned based on the treatment received.

Figure 2. Model flow. ADAS-cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; DAD, Disability Assessment for Dementia.

During the simulation, the next event for each simulated patient was identified, and the model clock was then fast-forwarded to the next event time. Before the event was processed for its associated consequences, such as updates of disease severity and treatment status, all time-dependent outcomes, including costs of care, caregiver time, time alive at each stage of the disease, and time spent in an institution, were tallied and accumulated. If the event was death or end of model time, patients were forced to exit the model after recording relevant data on model outcomes. Otherwise, patients continued the simulation by proceeding to the next event until they died or the model time horizon was reached.

Model parameters and data sources

Model settings

The base-case analyses were simulated based on 1,000 patients per treatment group for a total of 100 replications to obtain reliable results. The model time horizon and duration of treatment were set to 10 years for the base-case analyses. Costs and health benefits beyond 1 year were discounted at 5% per annum, in accordance with the current IQWiG guidelinesCitation23. Additionally, physician visits and updates of disease status were set on a 90-day cycle. In order to measure the amount of time that patients stayed alive at each specific stage of the disease and to assign proper costs of care for patients based on their disease severity, the severity evaluation was divided into five stages based on ADAS-cog and MMSE scores. Accordingly, AD was labelled as mild (ADAS-cog: 0–12; MMSE: 26–30), mildly moderate (ADAS-cog: 13–23; MMSE: 21–25), moderate (ADAS-cog: 24–35; MMSE: 16–20), moderately severe (ADAS-cog: 36–46; MMSE: 11–15), or severe (ADAS-cog: 47–70; MMSE: 0–10). Such a categorisation is similar to the categorisation based on MMSE scores used by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UKCitation28. Conversion between ADAS-cog and MMSE in the analyses was performed using a published equation (i.e., ADAS-cog = 70 − 2.33 × MMSE)Citation26.

Model population

This model carries a library of actual patient profiles from 1,595 patients enrolled in the two galantamine clinical trials (i.e., USA-1 and USA-10 trials)Citation9,Citation10. Baseline demographic characteristics were similar in the two trials. Enrolees in the USA-1 trial had a mean age of 75 years, 62% were females, and the mean psychiatric scores were 25 for the ADAS-cog, 11 for the NPI, and 71 for the DAD scalesCitation9. Enrolled patients in the USA-10 trial had a mean age of 77 years, 64% were females, and the mean scores were 29 for the ADAS-cog, 12 for the NPI, and 66 for the DAD scalesCitation10. Because the USA-10 trial did not collect DAD scores at baseline and USA-1 trial did not collect NPI scores at baseline, these scores were imputed using a regression equations derived from the USA-10 and USA-1 data, respectively. The main advantage of using actual patient data for creation of simulated patients is that the model population would closely resemble patients in actual life.

Because the trial population was not representative of individuals with AD in Germany, where more than 70% of the patients are female and almost 65% are ≥80 years old compared to 63% female and 36% with age 80 years or older among the trial population, the age and gender distributions of patients with AD in Germany as reported on the website of the German Federal Health MonitoringCitation29 were used to assign sampling weights to the patient profiles. This ensured that the simulated model population was representative of patients in Germany in terms of age and gender. As galantamine is not licensed in Germany for patients in the severe stage of the disease, patients with MMSE ≤10 (equivalent to ≥47 based on ADAS-cog scale) were excluded from the analyses.

Disease progression

Decline in ADAS-cog

For patients receiving no-drug treatment, the model predicted ADAS-cog scores based on a quadratic equation obtained from a prospective study by Stern and colleaguesCitation30. The equation is as follows: ADAS-cog (it) =6.040 + 1.329Xi − 0.005Xi2 + (0.032 + 0.037Xi − 0.00047XiCitation2) × T, where ADAS-cog(it) is the predicted score on the cognitive function for patient i at time t, X is the ADAS-cog score at time 0 for patient i, and T is the time, in months, since the first score was obtained.

For patients treated with galantamine, their ADAS-cog scores are predicted based on whether patients respond to the treatment or not. The efficacy data for galantamine were obtained from internal analyses of data pooled from six different clinical trials for galantamineCitation9,Citation10,Citation25,Citation31–33. Changes in ADAS‐cog during the study period were estimated based on response status. The criteria for responders used in the analyses were defined as change in ADAS‐cog score ≤0 at the end of study period and being stable or improved on global, functional, or behavioural assessment. The proportions of patients responding to treatments and the rates of change in ADAS‐cog scores based on response status are shown in . During the simulation, these efficacy data were applied only during the first year of treatment. Continued treatment after 1 year was assumed to serve as a maintenance function only and have no further benefits. Therefore, prediction of ADAS‐cog scores following the first year of treatment was simulated using two approaches. If patients remained on treatment, the same quadratic equation from Stern and colleaguesCitation30 was employed, but the ADAS‐cog score at the end of 1 year was used as the baseline score in the equation. If patients stopped treatment at any time point, their ADAS‐cog score increased linearly over a period of 1.5 monthsCitation34 following treatment discontinuation to a level that was equivalent to their identical twin who received no‐drug treatment from the start of the model up to that time point.

Table 1. Model parameters and data sources.

The same approach was used to predict ADAS‐cog scores for patients treated with ginkgo biloba. Data used to predict change in ADAS‐cog scores during the first year of treatment were obtained from a randomised, placebo‐controlled, double-blind clinical trial in which the efficacy of ginkgo biloba 240 mg per day for 26 weeks versus placebo was assessed based on 513 subjects with ADCitation35. Patients receiving ginkgo biloba showed an average decline in ADAS-cog scores of 1.3 over the trial duration (). As the study did not report the efficacy data by response status, the mean rate of change was applied to all patients treated with ginkgo biloba during the first year of treatment.

Update of DAD and NPI

The model predicts the rate of decline in DAD and NPI scores based on MMSE scores. Data used to estimate the rates of decline in DAD and NPI scores were obtained from the pooled data of galantamine trials ()Citation9,Citation10,Citation25,Citation31–33. During the simulation, patients’ DAD and NPI scores were updated based on the rates of decline and the duration of time that had elapsed since the last update. It was assumed that DAD and NPI scores stayed the same if patients experience no decline in cognitive function.

Treatment discontinuation

In this model, patients could stop treatment for any one of three reasons: reaching the end of the treatment duration (i.e., 10 years in the base-case analysis); progression to the severe stage of the disease (i.e., ADAS-cog ≥47); or other reasons. Patients who stopped galantamine or ginkgo biloba were assumed to lose all treatment benefits over the course of 1.5 monthsCitation34. Discontinuation for other reasons was applied for galantamine using pooled data from galantamine clinical trials and their extended studies with 4 years of follow-upCitation9,Citation10,Citation25,Citation31–33 and for ginkgo biloba using 1-year (2009) data from Insight Health Patient Tracking, a German claims database covering 10% of pharmacy prescriptions and dispensing for the statutory health insured patients. Risk of treatment discontinuation for patients on ginkgo biloba was very high during the first year of treatment, especially during the first 3 months. The annual risk of discontinuation after the first year for the ginkgo biloba group was derived from the last 3 months of the data and was assumed to remain constant over time. The risk of discontinuation for patients on galantamine was much lower than that for patients receiving ginkgo biloba and stable over a 4-year time interval. Thus, its average annual risk was assumed to remain constant over time. The risks of treatment discontinuation for galantamine and ginkgo biloba are listed in .

Survival

Survival is predicted based on patient's gender and age at baseline. A Gompertz function for each gender was fitted using mortality data from the 2006 German Life TableCitation36 among the population aged 40 years and older (). Furthermore, to account for the adverse impact of AD on survival, a hazard ratio of 2.1 obtained from a published studyCitation37 was applied to obtain the final survival time for each patient.

Costs

Direct medical costs considered in the analyses included treatment for AD, physician visits, and long-term-care insurance. All cost inputs used 2009 vales as shown in . Daily treatment costs of €4.18 for galantamine was based on a weighted cost of 83% of the patients receiving a daily dose of 16 mg and 17% 24 mg/dayCitation38,Citation39. Daily treatment cost of €2.20 for ginkgo biloba was estimated based on a daily dose of 240 mgCitation40. All patients were assumed to have an office visit every quarter to renew the prescription. Neurologist visits in Germany were on reimbursed with an average lump sum payment of €31.40 per quarter. This fee covered basic services such as physical examination, consultation, and prescriptions. The payment was made once per patient per quarter, independent of the actual number of visitsCitation41.

The monthly costs of long-term-care insurance () by location of care and disease severity were based on the data from the 2009 Federal Ministry of HealthCitation42. The location of care based on disease severity was determined using data from Kulp and colleagues ()Citation43. In the base-case analyses, patients who were institutionalised were assumed to claim benefits from long-term-care insurance coverage. For patients remaining at home or in the community, only a certain proportion of patients required long-term care, depending on their severity level (). Data from Gräßel and colleagues were used to determine the proportion of AD patients remaining at home who would require claims from the long-term-care insurance cover based on their disease severityCitation44.

Caregiver time

Caregiver time was predicted based on patients’ DAD scores. Data used for this prediction were obtained from a study by Feldman and colleaguesCitation45. In this study, caregiver time was measured as the total time spent assisting patients on all DAD domains and categorised into ‘paid’ and ‘informal’ time (i.e., time spent by family members, friends, or other non-paid carers). Based on the study, the amount of caregiver time increased as patient's ability to perform activities of daily living decreased. In the present model, only costs associated with ‘paid’ time were considered. Data from this study were fitted to a polynomial equation using DAD scores as the independent variable (i.e., caregiver hours per 2 weeks = −0.0002 × DAD3 + 0.0335 × DAD2 − 2.3358 × DAD + 59.4). Estimates of the cost of caregiver time were based on a rate of €5.50 per hour obtained from a German cost-effectiveness studyCitation46.

Analyses

Model outcomes, including survival, time alive at each severity stage, time spent institutionalised, caregiver time, and related costs, were calculated for each treatment group. As stated in the IQWiG guidelines, economic evaluation in a health technology assessment in Germany focuses on ensuring that there is efficiency in managing a specific therapeutic area rather than the entire healthcare systemCitation23. Thus, this analysis did not include quality-adjusted life-years but relied on other clinical outcomes, including time spent in institutional care or in severe stage of the disease.

Extensive one-way sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the impact of a specific parameter on the model outcomes. Subgroup analyses, based on disease severity, were also conducted to examine the way results varied across patient groups with different severities. In order to account for uncertainties from multiple key parameters, probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed by simultaneously varying the following parameters: (1) proportion of patients on galantamine responding to treatment, (2) changes in ADAS-cog scores over the first year of treatment, (3) risks of treatment discontinuation, (4) proportion of patients living at home categorised by disease severity, (5) monthly costs for long-term-care insurance based on severity, and (6) hazard ratio of death for AD.

For some of the parameters included in the probabilistic sensitivity analyses, standard errors were available from the parameter source data and thus used to measure parameter uncertainty. Where a standard error was not available for a selected parameter, we used 25% of the mean as an assumed standard error. It was assumed that parameters on continuous variables were normally distributed and categorical variables beta distributed. In both cases, the mean and standard errors were used to estimate the distribution of each selected parameter.

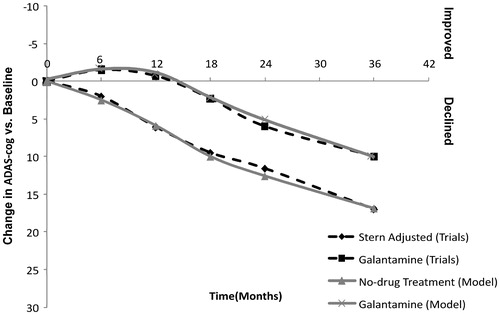

Model validation

Before carrying out the base-case analyses, technical validations were performed. These involved checking the results for accuracy and logical consistency. Furthermore, analyses were conducted to compare the model results against the trial results. In these validation analyses, changes in ADAS-cog scores over 3 years from baseline were compared to those observed in the galantamine trials. As shown in , the validation results indicate that the model closely predicts the changes in cognitive function observed in the trials for patients treated with placebo and galantamine.

Results

Base-case analyses

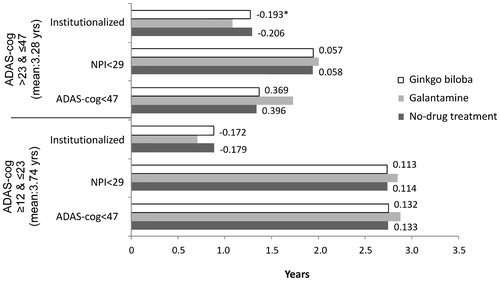

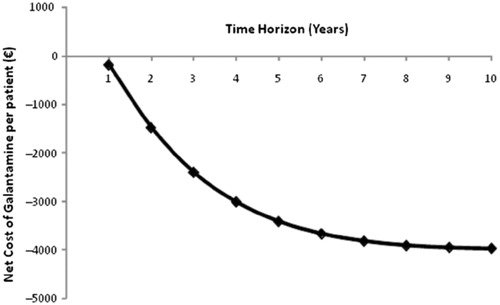

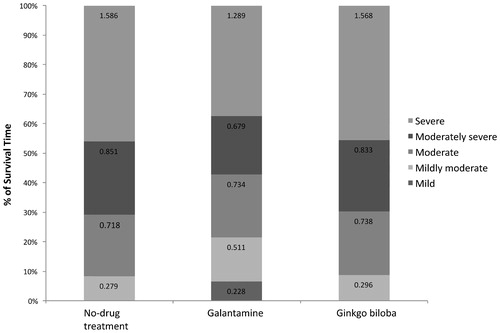

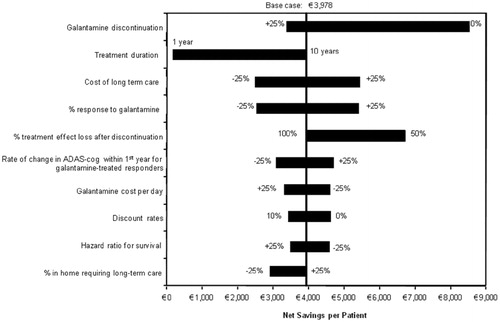

At the start of simulation, model patients had a mean age of 81 years, and mean scores of 27 on ADAS-cog, 11 on NPI, and 66 on DAD scales. The base-case analysis shows that the average survival time for the model population is 3.44 years (discounted) over 10 years of simulation. The survival time alive relative to severity stage for each treatment group is shown in . Galantamine delays time to severe stage of the disease and reduces time spent institutionalised. Compared to patients receiving no-drug treatment and ginkgo biloba, patients treated with galantamine on average stay 3.57 and 3.36 months longer, respectively, with ADAS-cog scores below 47 (i.e., not in severe stage of the disease), and 1.62 and 1.56 months longer, respectively, with NPI scores below 29, which has been identified as the threshold for serious behavioural disturbances ()Citation47. Moreover, time spent in institutional care for patients on galantamine is 2.34 months shorter than those receiving no-drug treatment and 2.21 months shorter than those who received ginkgo biloba. Galantamine also reduces caregiver time by 113 hours compared to both no-drug treatment and ginkgo biloba (). The gains in clinical benefits from the use of galantamine are projected to yield net savings of €3,978 compared to no-drug treatment and net savings of €3,972 compared to ginkgo biloba (), which mainly results from the reduction in long-term-care insurance cost.

Figure 4. Survival by disease severity based on ADAS-cog scores (mean survival: 3.442 years). ADAS-cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive scale.

Table 2. Base-case results (per patient over 10 years).

Subgroup analyses

The disease severity outcomes for patients with ADAS-cog scores 12–23 (mild to mildly moderate) and 24–46 (moderate to moderately severe) at baseline are shown in . Similar to the base-case results, galantamine remains more effective across all patient groups in delaying disease progression and reducing time spent in institutional care compared to no-drug treatment strategy and ginkgo biloba. The incremental gains of galantamine relative to other comparators are not so much different between different severity groups. The overall net savings resulting from use of galantamine relative to no-drug treatment and ginkgo biloba are also similar between patient groups, with slightly greater net savings in patients with moderate to moderately severe AD. Additional analyses were conducted to see the impact of patient's age on the amount of net savings that could result from the use of galantamine. The results show net per-patient savings of €7,278 compared with no-drug treatment and €7,256 compared with ginkgo biloba if patients who are ≤60 years old are considered. In the case of patients between the ages of 61 and 70 years, the net savings per patient are €6,908 compared with no-drug treatment and €6,914 compared with ginkgo biloba.

Sensitivity analyses

Changes in net savings resulting from the use of galantamine over a 10-year period relative to no-drug treatment strategy are displayed in . The results indicate that the net savings are greatly dependent on the length of period considered by decision makers. Changes in net savings tend to level off as the time horizon increases. This is because the model population has a relatively short life expectancy. In addition to model time horizon, model parameters with a significant impact on the net savings when compared with no-drug treatment strategy include treatment discontinuation, duration of treatment, percentage of responders to galantamine, level of decrement in treatment effect after discontinuation, and mean change in ADAS-cog scores during the first year of treatment (). The results of the one-way sensitivity analyses based on the comparison of galantamine versus ginkgo biloba are very similar to those seen in .

Figure 7. Results of univariate sensitivity analyses (compared to no-drug treatment). ADAS-cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive scale.

The results of probabilistic sensitivity analyses suggest that the differences in total cost between galantamine and no-drug treatment strategy could vary from a net expense of €871 to a net saving of €9,846 per patient, with a mean net savings of €2,842. Only 0.22% of the 1,000 replications indicate that galantamine would incur a greater expense than no-drug treatment strategy. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses revealed similar results in comparison to ginkgo biloba, ranging from a net expense of €807 to a net saving of €9,654 per patient, with a mean saving of €2,905. Only 0.17% of the 1,000 replications show that use of galantamine would result in a greater expense than ginkgo biloba.

Discussion

The present analyses predict that compared to no-drug treatment and ginkgo biloba, treatment with galantamine in patients with mild-to-moderate AD reduces overall costs of care, delays reaching severe stage of the disease, and delays time to require institutional care. These predicted clinical and economic benefits could be even greater if only younger patients were considered in the model. This is because more patients would progress to the severe stage of the disease due to a longer life expectancy, which allows a greater amount of time alive with severe disease to be avoided by galantamine. Since the mean age of the model population in the base-case analyses is 81 years, most of them died within 2–3 years of entering the model before they progressed to the severe stage of the disease. This may explain the reason for slower rate of increased savings as the model time horizon exceeds the third year and reaches its maximum at about 10 years. In addition, the shorter survival time of the model population in the base-case analyses also explains why the net clinical benefits and savings are similar between different severity groups, as seen from the results of the subgroup analyses. When considering only patients with age less than 60 years, the net savings per patient resulting from the use of galantamine versus no-drug treatment in patients with mild to mildly moderate disease are €1,501 (€7,893 vs. 6,392) greater than in patients with moderate to moderately severe disease. Similar results were observed when compared with ginkgo biloba.

Although the one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses indicate that the amount of net savings could vary substantially, it is almost certain that galantamine remains a superior treatment option compared with no-drug treatment strategy and ginkgo biloba in terms of delaying disease progression and reducing the overall costs of care in Germany. In the current analyses, the model outcomes between no-drug treatment and ginkgo biloba are similar because more than 60% of the patients receiving ginkgo biloba discontinued the treatment within first 3 months and more than 80% of the patients stopped the treatment by the end of the first year. From the published and public domain data gathered for this study, the reasons for the high rate of non-persistence of treatment with ginkgo biloba are not clear. The dominance of galantamine over ginkgo biloba persists even if perfect adherence was assumed since a net savings of €2,571 per patient can still be expected based on this scenario.

The cost effectiveness of galantamine in the treatment of mild-to-moderate patients with AD has been evaluated in both AHEAD and NICE modelsCitation15,Citation16,Citation28. These two models used the concept of need for FTC and modelled disease progression in three possible health states: pre-FTC, FTC, and death. The delay in time to FTC after treatment with galantamine was predicted in the AHEAD model to be approximately 2.5–3.18 months compared to no-drug treatment strategy over a 10-year time horizon and to be approximately 1.5 months over a 5-year timeframe in the NICE model. Although the need for FTC is not modelled as an outcome in the present model, the analyses shows that galantamine reduces the time spent in institutional care by about 2.4 months over the 10-year time horizon compared to a no-drug treatment strategy. This estimate is similar to the results predicted in both AHEAD and NICE models. Despite the similarity in clinical benefits, the estimated incremental costs associated with the use of galantamine relative to no-drug treatment in the present analyses are different from those estimated in the NICE and AHEAD models. Both models, especially the NICE model, predicted that galantamine would increase the overall costs of care for patients with AD compared to the no-drug treatment strategy. Several factors may have contributed to the observed inconsistencies such as differences in cost structures and data between the UK and Germany, different model time horizons used, and differences in methods used to model disease progression and capture potential economic benefits associated with treatments. With the capabilities provided by DES, disease progression in the present model is simulated based on a series of continuous scales – ADAS-cog, MMSE, NPI, and DAD – unlike NICE and AHEAD models that dichotomised disease progression into pre-FTC and FTC. The approach used in the present analyses allows the costs to be measured on a finer gradient, enabling the potential economic benefits of galantamine to be fully captured.

A recent economic study assessing the cost effectiveness of donepezil in the treatment of mild-to-moderate AD was also conducted using a DESCitation48. Both models have a similar structure in terms of how disease progression is simulated over time, but are different in country of interest for the analysis (UK vs. Germany), comparators, primary outcome measures (quality-adjusted life-years versus disease-specific outcomes such as time spent in institutional care), and data used. Despite these differences, both models predict similar clinical and economic benefits for the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of patients with mild-to-moderate AD compared to no-drug treatment strategy. In the analyses conducted by Getsios and colleaguesCitation48, donepezil increased time alive with MMSE scores above 10 (i.e., equivalent to ADAS-cog scores below 47) by about 3–6 months and reduced time alive with NPI scores above 29 by about 1–2 months and time spent in institutional care by about 2–3 months when compared with a no-drug treatment strategy. These outcomes are very close to the clinical benefits of galantamine predicted in the current evaluation. Moreover, both models predict net savings resulting from the use of cholinesterase inhibitors when compared to no-drug treatment strategy.

As with other models, the present model has several limitations. Despite the availability of long-term data regarding the benefit of galantamine in nursing home placementCitation49, efficacy data regarding the impact of galantamine on cognitive function were based on trials with shorter follow-up periods. Consistent with many other modelling studies in this therapeutic areaCitation48, continued treatment after 1 year was assumed to have a maintenance function only and no further treatment benefits in terms of delaying disease progression were assumed. All clinical benefits of treatment were assumed fully lost within 6 weeks following treatment discontinuationCitation34,Citation48. In addition, comparisons with ginkgo biloba are subject to a great uncertainty as no head-to-head trial data are available. Future direct or indirect comparative data between galantamine and ginkgo biloba would further improve these analyses and provide results that are more robust. Nevertheless, it should be noted that a recent systematic review indicated that most of the recent clinical trials showed no significant differences in cognition and activities of daily living between ginkgo biloba and placebo suggesting that the clinical benefits of ginkgo biloba in patients with dementia remain uncertainCitation50. Thus, based on the existing data, it is reasonable to conclude that the results of the present analyses are robust despite the lack of direct comparative data between galantamine and ginkgo biloba. Other limitations concerned the prediction of ADAS-cog, DAD, and NPI scores based on calculated values. Although the results of this study are similar to those reported in different studies, incorporation of other relevant factors may have further enhanced the accuracy of prediction in disease progression. In addition, the data for costs of long-term care insurance were based entirely on the level of severity as defined by MMSE ranges and not behavioural and functional scores. However, it may be argued that behavioural symptoms are often issues more for the nursing home placement of AD patientsCitation51. Similarly, the data for caregiver time are entirely based on DAD scores. These outcomes may be more accurately predicted for each individual patient if other relevant patient characteristics would have been incorporated or were available. In addition, the data used to estimate caregiver time may not be representative as they are not completely based on German populations. New data for caregiver time collected from representative German populations would be likely to further improve the accuracy of our estimates. The costs of long-term care insurance are reimbursed in Germany based on levels of care, which were assumed equivalent irrespective of the severity stage of the disease based on MMSE scores. Finally, in order to achieve a refined gradient of costs, the costs of care were linearly interpolated into five severity ranges. Such assumptions and interpolations of the data cannot be evaluated based on the available data and thus may have introduced a level of uncertainty in the estimates.

Conclusion

The present analyses suggest that galantamine not only improves clinical benefits in terms of delaying disease progression and reducing time spent institutionalised, but also achieves savings in healthcare costs associated with the care of patients with mild-to-moderate AD in Germany. The potential cost savings could be substantially increased if galantamine is used to treat patients of an even younger age and those with less severe AD than is the current practice. These results, however, may be limited by lack of long-term comparative efficacy data as well as data on long-term care costs based on multiple outcome measures. The estimates of these analyses appear robust despite some of the limitations of the study. It is expected that collection of long-term clinical and cost data based on different relevant factors will likely enhance the cost-effectiveness evaluation for galantamine.

Transparency

Declaration of funding:

This work was supported in part by a grant from Janssen-Cilag.

Declaration of financial/other relationships:

S.G., L.H. and R.W. have disclosed that they are employees of United BioSource Corporation, a consultancy that has funding for this study. M.G. has disclosed that she is an employee of Janssen-Cilag, Neuss, Germany.

References

- Cummings JL. Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:56–67

- Alzheimer's Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2009, London 2009

- Mahlberg R, Gutzmann H. Diagnostik von Demenzerkrankungen. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 2005;102:A2032–2039

- Forsyth E, Ritzline PD. An overview of the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of Alzheimer disease. Phys Ther 1998;78:1325–1331

- BMG. Available at: http://www.bmg.bund.de/cln_110/nn_1168278/SharedDocs/Standardartikel/DE/AZ/D/Glossarbegriff-Demenz.html. Accessed 5 December 2008

- Wimo A, Winblad B, Jönsson L. The worldwide societal costs of dementia. Alzheimers Dement 2009;6:98–103

- Jönsson L, Wimo A. The cost of dementia in Europe: a review of the evidence, and methodological considerations. Pharmacoeconomics 2009;27:391–403

- Cummings JL. Treatment of Alzheimer's disease: current and future therapeutic approaches. Rev Neurol Dis 2004;1:60–69

- Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Wessel T, et al. Galantamine in AD: a 6-month randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a 6-month extension. The Galantamine USA-1 Study Group. Neurology 2000;54:2261–2268

- Tariot PN, Solomon PR, Morris JC, et al. A 5-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of galantamine in AD. The Galantamine USA-10 Study Group. Neurology 2000;54:2269–2276

- Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG). Cholinesterasehemmer bei Demenz, Abschlussbericht, Auftrag A05-19A, 07.02.2007, www.iqwig.de

- Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG). Aktualisierungsrecherche zum Bericht A09-19A (Cholinesterasehemmer bei Demenz). Rapid Report, Auftrag A09-03, 12.10.2009, www.iqwig.de

- Sano M, Wilcock GK, van Baelen B, et al. The effects of galantamine treatment on caregiver time in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;18:942–950

- Feldman HH, Pirttila T, Dartigues JF, et al. Treatment with galantamine and time to nursing home placement in Alzheimer's disease patients with and without cerebrovascular disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;24:479–488

- Caro JJ, Getsios D, Migliaccio-Walle K, et al. Assessment of health economics in Alzheimer's disease (AHEAD) based on need for full-time care. Neurology 2001;57:964–971

- Ward A, Caro JJ, Getsios D, et al. Assessment of health economics in Alzheimer's disease (AHEAD): treatment with galantamine in the UK. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;18:740–747

- Migliaccio-Walle K, Getsios D, Caro JJ, et al. Economic evaluation of galantamine in the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease in the United States. Clin Ther 2003;25:1806–1825

- Caro JJ, Salas M, Ward A, et al. Assessment of Health Economics in Alzheimer's Disease. Economic analysis of galantamine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, in the treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease in the Netherlands. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2002;14:84–89

- Garfield FB, Getsios D, Caro JJ, et al. Assessment of Health Economics in Alzheimer's Disease (AHEAD): treatment with galantamine in Sweden. Pharmacoeconomics 2002;20:629–637

- Getsios D, Caro JJ, Caro G, et al. Assessment of health economics in Alzheimer's disease (AHEAD): galantamine treatment in Canada. Neurology 2001;57:972–978

- Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss (G‐BA). Arzneimittelrichtlinie – Anlage III: Übersicht über Versorgungseinschränkungen und –ausschlüsse in der Arzneimittelversorgung durch die Arzneimittelrichtlinie und aufgrund anderer Vorschriften (§ 34 Abs. 1 Satz 6 und Abs. 3 SGB V), 19.02.2010

- Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss (G‐BA). Ergänzungsauftrag zur Nutzenbewertung von Cholinesterasehemmern zur Behandlung der Alzheimer Demenz. 18.12.2009, http://www.g-ba.de/downloads/39-261-1075/2009-12-17-IQWiG-Cholinesterasehemmern.pdf

- Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG). Allgemeine Methoden zur Bewertung von Verhältnissen zwischen Kosten und Nutzen. Version 1.0, 12.10.2009, www.iqwig.de

- Caro JJ. Pharmacoeconomic analyses using discrete event simulation. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23:323–332

- Wilcock GK, Lilienfeld S, Gaens E. Efficacy and safety of galantamine in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: multicentre randomised controlled trial. Galantamine International-1 Study Group. Br Med J 2000;321:1445–1449

- Caro J, Ward A, Ishak K, et al. To what degree does cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease predict dependence of patients on caregivers? BMC Neurol 2002;2:6

- Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG). Ginkgohaltige Präparate bei Alzheimer Demenz. Auftrag A05-19B, Abschlussbericht. 29.09.2008, www.iqwig.de

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine (review) and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. MidCity Mace, London, November 2006. Available at: www.nice.org.uk. Accessed 9 December 2008

- Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. Available at: http://www.gbe-bund.de/. Accessed 15 November 2009

- Stern RG, Mohs RC, Davidson M, et al. A longitudinal study of Alzheimer's disease: measurement, rate, and predictors of cognitive deterioration. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:390–396

- Wilkinson D, Murray J. Galantamine: a randomized, double-blind, dose comparison in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:852–857

- Rockwood K, Mintzer J, Truyen L, et al. Effects of a flexible galantamine dose in Alzheimer's disease: a randomized, controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;71:589–595

- Brodaty H, Corey-Bloom J, Potocnik FCV, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of galantamine prolonged- and immediate-release formulations in the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2005;20:120–132

- Aronson SM, Baelen B van, Kershaw P. Greater benefits for patients receiving sustained vs. interrupted treatment with galantamine. The 9th International Conference on Alzheimer's Disease and Related Diseases, Philadelphia, USA, July 17–22, 2004

- Schneider LS, DeKosky ST, Farlow MR, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of two doses of ginkgo biloba extract in dementia of the Alzheimer's Type. Curr Alzheimer Res 2005;2:541–551

- German Life Table 2006. Available at: http://www.mortality.org/hmd/DEUTNP/STATS/mltper_1x1.txt. Accessed 15 October 2009

- Fitzpatrick AL, Kuller LH, Lopez OL, et al. Survival following dementia onset: Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci 2005;229:43–49

- IMS Health, IMS Disease Analyzer, Jan 2008 – Dec 2008 JC data on file. IMS Health Deutschland. http://www.imshealth.de/sixcms/detail.php/307, letzter Zugriff 20.01.2010

- Lauer-Taxe Online, www.lauer-fischer.de. Accessed 20 October 2009

- Schwabe U, Paffrath D (Hrsg.). Arzneiverordnungsreport 2008. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2008:305–317

- Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung.Einheitlicher Bewertungsmaßstab, Stand 01.01.2009, http://www.kbv.de/ebm2010/ebmgesamt.htm. Accessed 4 November 2009

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. www.bmgs.de. Accessed 27 October 2009

- Kulp W, Graf v.d. Schulenburg J-M. Pharmakoökonomische Aspekte der Behandlung von Demenz-Patienten. Pharmazie unserer Zeit 2002;31:410–416

- Gräßel E, Donath C, Lauterberg J, et al. Demenzkranke und Pflegestufen: Wirken sich Krankheitssymptome auf die Einstufung aus? Gesundheitswesen 2008;70:129–136

- Feldman HH, Van Baelen B, Kavanagh SM, et al. Cognition, function, and caregiving time patterns in patients with mild‐to-moderate Alzheimer disease: a 12-month analysis. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2005;19:29–36

- Teipel SJ, Ewers M, Reisig V, et al. Long-term cost-effectiveness of donepezil for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007;257:330–336

- Tun SM, Murman DL, Long HL, et al. Predictive validity of neuropsychiatric subgroups on nursing home placement and survival in patients with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;15:314–327

- Getsios D, Blume S, Ishak KJ, et al. Cost effectiveness of donepezil in the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: a UK evaluation using discrete-event simulation. Pharmacoeconomics 2010;28:411–427

- Feldman HH, Pirttila T, Dartigues JF, et al. Treatment with galantamine and time to nursing home placement in Alzheimer's disease patients with and without cerebrovascular disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;24:479–488

- Birks J, Grimley Evans J. Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; CD003120

- Weyerer S. Altersdemenz. Robert-Koch-Institut (RKI) (ed.) Gesundheitsberichtserstattung des Bundes – Heft 28. 15.11.2005, www.rki.de