Abstract

Objectives:

This study examines costs for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor positive (HR+) metastatic breast cancer (mBC).

Methods:

Data were obtained from the IHCIS National Managed Care Benchmark Database from 1/1/2001 to 6/30/2006. Women aged 55–63 years were selected for the study if they met the inclusion criteria, including diagnoses for breast cancer and metastases, and at least two fills for a hormone medication. Patients were followed from the onset of metastases until the earliest date of disenrollment from the health plan or 6/30/2006. Patient characteristics were examined at time of initial diagnoses of metastases, while costs were examined post-diagnosis of metastases and prior to receipt of chemotherapy (pre-chemotherapy initiation period) and from the date of initial receipt of chemotherapy until end of data collection (post-chemotherapy initiation period). Costs were adjusted to account for censoring of the data.

Results:

The study population consisted of 1,266 women; mean (SD) age was 59.05 (2.57) years. Pre-chemotherapy initiation, unadjusted inpatient, outpatient, and drug costs were $4,392, $47,731, and $5,511, while these costs were $4,590, $57,820, and $38,936 per year, respectively, post-chemotherapy initiation. After adjusting for censoring of data, total medical costs were estimated to be $55,555 and $70,587 in the first 12 months and 18 months, respectively in the pre-chemotherapy initiation period. Post-chemotherapy initiation period, 12-month and 18-month adjusted total medical costs were estimated to be $87,638 and $130,738.

Limitations:

The use of an administrative claims database necessitates a reliance upon diagnostic codes, age restrictions, and medication use, rather than formal assessments to identify patients with post-hormonal women with breast cancer. Furthermore, such populations of insured patients may not be generalizable to the population as a whole.

Conclusions:

These findings suggest that healthcare resource use and costs – especially in the outpatient setting – are high among women with HR+ metastatic breast cancer.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the primary carcinoma diagnosis, apart from skin malignancy, and the second most common cause of cancer death among women in the United StatesCitation1. An estimated 207,090 new cases of invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed among US women during 2010Citation1, and in 6% of those cases the cancer will have already metastasizedCitation2. Once breast cancer metastasizes, it is nearly always fatal, with 1996 research illustrating that further tumor progression occurs within 5–10 years in 95–98% of casesCitation3), and with the average survival time after diagnosis of metastasis being approximately 24 monthsCitation4,Citation5. In addition to impaired survival, metastatic breast cancer is also associated with a wide range of negative quality of life factors, including decreased physical, role, and social functioningCitation6; psychological morbidityCitation7; and morbidity related to the site of metastasisCitation8–10.

The goals for treating patients with metastatic disease have traditionally been to prolong life and palliate or prevent symptoms through systemic treatment modalitiesCitation11. One important criterion for treatment selection in breast cancer depends on the hormone sensitivity of the tumor. The treatment modalities by hormonal status in turn have significant cost implications. Previous cost analyses in metastatic breast cancer have not delineated these costs by hormone status.

In postmenopausal cases, approximately 75% of breast cancers are estrogen-receptor-positive (ER+), 55% are progesterone-receptor-positive (PgR+), and 80% are either ER+ or PgR+Citation12,Citation13. The primary categories of treatment for HR+ metastatic breast cancer are endocrine therapy and chemotherapyCitation14,Citation15. In women with slowly progressive HR-positive metastatic breast cancer, endocrine therapy rather than chemotherapy is considered as the first-line treatmentCitation14,Citation15, since endocrine therapy is less toxic and associated with a longer response period and equal success at increasing survivalCitation15,Citation16. For almost two decades, the standard of care for all women with HR-positive breast cancer, in both adjuvant and first-line metastatic settings, was tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulatorCitation15,Citation17,Citation18.Third-generation aromatase-inhibitors (AIs) have replaced tamoxifen in recent years as the preferred treatment option for postmenopausal women with HR-positive advanced breast cancer, both in neo-adjuvantCitation19,Citation20 and adjuvant settingsCitation19,Citation21, and for metastatic diseaseCitation15,Citation19. Relative to tamoxifen, AIs are better at delaying the emergence of resistance to treatmentCitation22; however, locally advanced and metastatic breast cancers will eventually become resistant to any type of hormonal therapyCitation20,Citation22.

In cases where the breast tumor is resistant to endocrine therapy, cytotoxic chemotherapy is an alternative treatment optionCitation14,Citation15. Chemotherapies are associated with significant negative side-effects, including fever or infection, low white blood cell or platelet count, nausea, diarrhea, malnutrition/dehydration, and hemoptysisCitation21,Citation23. In prescribing chemotherapies, it is thus necessary to weigh any potential benefits of treatment, such as increased relapse-free interval or improved survival, against the costs, in terms of both dollars spent and toxicityCitation24–26. However, no study to the authors’ knowledge has focused on estimating the total healthcare cost of managing hormone receptor positive patients on chemotherapy.

Thus, there are limited data with regard to the healthcare resource use and costs incurred by patients with HR+ metastatic breast cancer undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy treatment. The purpose of this study is to determine direct healthcare costs for post-menopausal women who have been diagnosed with HR+ mBC in two distinct phases of the natural disease progression (prior to and post-treatment with cytotoxic chemotherapy). In addition, the research will also study how these costs are distributed over time. The research will help to increase understanding of the resource implications and cost of managing postmenopausal women diagnosed with HR+ mBC.

Methods

Data for this study were obtained from the IHCIS National Managed Care Benchmark Database. The large, national database contains information on medical claims, inpatient confinements, outpatient pharmacy claims, laboratory results and membership eligibility. This retrospective database is fully de-identified and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant. The data for this study comprised medical, inpatient, and pharmacy claims with dates of service from January 1, 2001 through June 30, 2006.

The analysis focuses on postmenopausal women with mBC who were identified as being HR+. Specifically, to be eligible for inclusion, an individual had to be woman and have received at least two diagnostic claims of breast cancer (based upon receipt of an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code of 174.xx)Citation27. In addition, patients were required to have received at least two diagnostic claims of metastatic cancer (ICD-9-CM code of 196.xx–199.xx), with the first such diagnostic claim date identified as the index date. The pre-period was then defined as the 6 months prior to the index date. Third, individuals were required to be 55–63 years of age on their index date. This upper bound age restriction was selected because the IHCIS database does not contain Medicare insurance data. Therefore, restricting patients to be no older than 63 ensured that the study population consisted of only postmenopausal women with sufficient post-index follow up prior to patients being switched to Medicare insurance at age 65. Fourth, all individuals in the study received at least two claims associated with receipt of hormonal therapy (see )Citation28. Additionally, since the purpose of this research is to study healthcare costs among metastatic patients who receive hormonal therapy and then follow them over time, there were restrictions with regard to the timing of the hormonal therapy and chemotherapy. Specifically, patients with observed use of chemotherapy between the index date and the first follow-up hormone claim were removed from the study. Fifth, all patients were required to have continuous insurance coverage from a time period from the beginning of the pre-period through the end of the post-period. Finally, patients were excluded from the analyses if they were identified as having other types of cancer besides breast cancer 2–6 months before the index date, unless the individual also received a subsequent diagnosis of the same type of metastases.

Table 1. Hormonal agents.

Given this cohort, a subgroup of individuals who received chemotherapy post-index date was constructed. Chemotherapy agents considered in this analysis corresponded to medications listed in the AHFS Classification system as 10.00 (anti-neoplastic agents). For each of these agents, outpatient prescription drug use was considered if a claim was filled for any of the drugs of interest, while use at a facility was determined by examining receipt of a Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code. This subset consisted of 398 individuals. The study focuses on two distinct time periods post-index date. First, is the time period prior to receipt of chemotherapy (pre-chemotherapy initiation period). For patients who received chemotherapy this was defined as the time from index date to the day prior to first receipt of chemotherapy, while for patients who did not receive chemotherapy this time period is equal to the total time after index date for which data was available. The post-chemotherapy initiation period is thus defined as the time from initial receipt of chemotherapy through the end of the follow-up for individuals who received chemotherapy and as missing for individuals who did not receive chemotherapy. For individuals who received chemotherapy, at least one claim for hormonal therapy was required to be between the index date and date of first receipt of chemotherapy.

The primary objective of this study was to characterize the patients described above in terms of demographics and clinical characteristics, and costs. Patient characteristics include age, region of residence and type of insurance coverage. In addition, a modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), a measure of patient overall health status which omits breast cancer as condition for inclusion in the CCI, was constructed based upon the 6 months prior to the index dateCitation29.

Consistent with prior research, costs were measured as the allowed payments by the health plan to the providerCitation30. As such, deductible, co-insurance, and other cost sharing are not included in the measure of costs, allowing for more consistent comparisons across patients, data sources and geographic areas. All medical costs were converted to 2006 values using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI)Citation31. Total costs were subdivided into inpatient, outpatient, emergency room, and pharmacy (chemotherapy and other prescription drug) costs. As with resource utilization, unadjusted costs were examined in the first 6, 12, and 18 months pre-and post-chemotherapy initiation. In addition, costs were also adjusted to account for censoring using the method proposed by LinCitation32. Specifically, a weighted ordinary least squares regression model is fitted for those who have complete data over the time period of interest, where the weight is the inverse of the probability of not being censored at the end of each time interval, and is calculated from a logistic regression model. The multivariate analyses uses patient age, region of residence, modified Charlson score in the 6 months pre-index date, and year of index date as covariates.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all individuals. The number and percent of patients are presented for categorical variables while means and standard deviations are presented, at a minimum, for continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 120,406 patients were identified with breast cancer between January 1 2001 and June 30 2006. Of these, 17,828 were identified as having metastatic disease, 5,407 were aged 55–63 years at index date, and 1,689 were hormonal positive. Of these patients, 1,323 had continuous insurance coverage over the time period of interest. Excluding patients with evidence of other types of cancers resulted in the final sample of 1,266 women.

lists the patient characteristics of HR+ metastatic breast cancer patients. Mean age of patients was 59 years (SD: 2.57). The mean modified CCI score was 2.1, based upon the 6 months prior to the index date. In this database, individuals were followed for an average of slightly more than 2 years post-identification with metastatic breast cancer, with the mean number of days pre-chemotherapy initiation equal to 584 and the mean number of days post-chemotherapy initiation equal to 433.

Table 2. Characteristics of study population.

presents unadjusted healthcare costs per patient year both pre- and post-chemotherapy initiation. The average annual costs were $69,210 (±$84,273) pre-chemotherapy and $117,757 (±$93,893) post-chemotherapy initiation. Outpatient costs were the largest component of costs both pre- (68.97%) and post- (49.10%) chemotherapy initiation. Prescription drug costs were 7.96% of pre-chemotherapy costs and 31.66% of post-chemotherapy initiation costs.

Table 3. Unadjusted healthcare costs per patient-year.

In addition to examining costs on an annual basis, unadjusted costs for the 6, 12, and 18 months pre-and post-chemotherapy initiation were also examined. These results, presented in , revealed that after 1 year the mean pre-chemotherapy initiation total medical costs were $48,879 while the mean total medical costs 1 year post-chemotherapy initiation were $82,182. The largest share of costs occur in the first 6 months post-metastases diagnoses and first 6 months post-chemotherapy initiation. Costs were generally found to be higher post-chemotherapy initiation, with the largest increases in costs found among chemotherapy and outpatient costs. For example, the mean outpatient costs were $36,788 in the first 12 months of the pre-chemotherapy initiation time period, while such costs after a similar duration post-chemotherapy initiation were $43,163. In the pre-chemotherapy initiation period, the largest components of total medical costs were outpatient (73.82% after 6 months, 75.24% after 12 months, and 75.13% after 18 months), inpatient (17.59% after 6 months, 15.28% after 12 months, and 14.81% after 18 months), and prescription drug costs (8.18% after 6 months, 9.06% after 12 months, and 9.65% after 18 months). In the post-chemotherapy initiation period, chemotherapy costs represented 27.86%, 26.45%, and 26.38% of total medical costs after 6, 12, and 18 months, respectively.

Table 4. Unadjusted healthcare costs 6-month, 12-month and 18-month time periods.

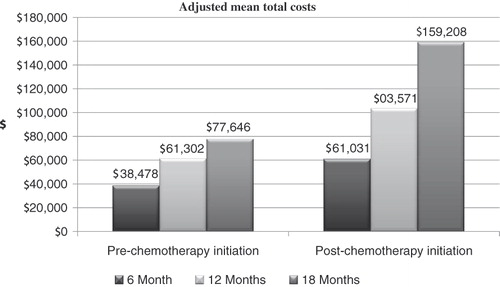

presents total costs in pre-and post-chemotherapy initiation period after adjusting for censoring of data. Total healthcare costs increased over time in both the pre- and post-chemotherapy initiation periods. After adjusting for censoring of data, total medical costs were higher in both the pre-and post-chemotherapy initiation time periods compared to unadjusted costs. Specifically, after 12 months adjusted costs were $61,302 (±$18,646) in the pre-chemotherapy initiation period and $103,572 (±$17,045) in the post-chemotherapy initiation period, compared to un-adjusted costs of $48,879 (±$51,433) and $82,182 (±$65,542) in the pre- and post-chemotherapy initiation periods, respectively.

Discussion

This descriptive analysis examined the patient characteristics, and costs for postmenopausal women with mBC who are HR+. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the among the first studies to examine costs in postmenopausal HR+ mBC patients. In addition, costs were examined both pre-and post-chemotherapy initiation.

One finding from this study was that the majority of patients (69%) with mBc did not receive chemotherapy. This finding is consistent with a treatment algorithm that suggests that hormonal therapy be applied first and chemotherapy used only if such hormonal therapy ceases to be effectiveCitation33. Furthermore, research has compared the effectiveness of the hormonal therapy tamoxifen to chemotherapy or chemotherapy plus tamoxifenCitation34. Results indicate that, at a median follow-up of 5 years, tamoxifen was significantly more effective than chemotherapy for postmenopausal womenCitation34. Results also showed that the chemotherapy added to tamoxifen was not more effective than use of tamoxifen alone in postmenopausal womenCitation34. In contrast, more recent research has shown that letrozole treatment with the chemotherapy agent trastuzumab is more effective in the treatment of mBC, compared to letrozole aloneCitation35.

Post-initial diagnosis of metastases, the average duration of follow-up was approximately 2 years (719.72 days). This duration is shorter than might be expected in this cohort, given that research has found a median survival time associated with metastatic breast cancer of 51 monthsCitation36. Of course, the database constructed here does not measure survival, so such comparisons should be viewed cautiously. In addition, by construction, women were not followed past age 65 due to limitations in information regarding their Medicare insurance coverage. For patients who were treated with chemotherapy, the mean period of time between diagnosis of metastases and initiation of chemotherapy was approximately 1 year (331.87 days; SD = 321.10 days). This finding suggests that chemotherapy is generally not being used as first-line therapy for these patients.

Previous research has also examined costs associated with a diagnosis of mBC. For example, Rao et al.Citation37 identified total healthcare costs to be approximately $34,000 a year after adjusting for inflation to 2006 dollars, while this study estimates total medical costs to be $43,614 in the first year post-diagnosis of metastases. These costs differences may be explained, at least partially, by the difference in cohorts. Specifically, the Rao study focused on mBC in general, while this study focuses on a cohort of hormone-positive, postmenopausal women. In the current study, the outpatient costs were found to be the largest component of total medical costs. However, this finding is in contrast to previous research that has found that inpatient costs were accounted for over 50% total costs associated with metastatic breast cancer in CanadaCitation38. Furthermore, in the current study, chemotherapy costs were found to account for approximately one-third of total medical costs. This finding is consistent with earlier research which has found that approximately 30% of total costs for treatment of postmenopausal metastatic breast cancer can be attributed to chemotherapyCitation39.

Results of this research also indicated that both the pre- and post-chemotherapy initiation time periods, the largest share of costs occur in the first 6 months. This finding is consistent with previous research from a 4-year longitudinal study that has shown that costs of breast cancer declined after years 1 to 2, with the exception of women with stage II breast cancerCitation40. The timing of costs suggests aggressive treatment at time of initial diagnosis of metastases as well as when it is decided that chemotherapy will be initiated may be utilized. As such, it would appear to be misleading to extrapolate long-term cost and resource implications from shorter term data in a linear fashion. This finding may help healthcare providers and managed-care organizations help to plan resource allocation over time. In addition, results indicate that there are differences between unadjusted costs and cost estimates that have been adjusted for the incompleteness of follow-up data. This result is not surprising given the large body of literature that has documented the importance of controlling for censoring of data when examining medical costsCitation41–46. As a result, naive analyses based solely upon summary statistics may result in misleading conclusions.

As with any research, the finding presented here should be interpreted within the context of the limitations of the study's design. First, this analysis was conducted using an administrative claims database and included only patients with medical and prescription benefit coverage. As such, these results may not generalize well to other populations. Second, it is less rigorous to rely on claims databases rather than upon formal diagnostic assessments for identifying patients for inclusion or exclusion in the analyses. For example, identification of breast cancer and metastases relied exclusively on ICD-9-CM codes, while identification women as postmenopausal relied on age restrictions and receipt of hormonal therapy. In addition, the use of such medical claims data precludes the use of patient assessments; as a result, the analysis cannot examine quality of life, functioning or any clinical outcomes. Finally, this study is purely descriptive in nature and does not control for the impact of any patient characteristics, such as severity of cancer or duration of disease, on resource utilization or costs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study findings suggest that healthcare resource use and costs – especially in the outpatient setting – are high among women with HR+ metastatic breast cancer. In addition, a large share of these costs are incurred in the initial 6-month post-identification with metastases as well as in the initial 6 months post-initiation on chemotherapy.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Support for this study was provided by Amgen.

Declaration of financial relationships:

M.L. has disclosed that she was compensated by Amgen for her work on this research. B.B. and S.G. have disclosed that they are employees of Amgen and R.B. has disclosed that he was employed by Amgen during the time of his work on this research.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Patricia Platt for providing technical writing and editing for the manuscript.

References

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Overview. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2009. Available at http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/overviewguide/breast-cancer-overview-key-statistics. [Last accessed 12 September 2010]

- Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al. (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2005, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005/, based on November 2007 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2008. [Last accessed 27 November, 2009]

- Greenberg PA, Hortobagyi GN, Smith TL, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with complete remission following combination chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:2197-2205

- Gennari A, Conte P, Rosso R, et al. Survival of metastatic breast carcinoma patients over a 20-year period. Cancer 2005;104:1742-1750

- Giordano SH, Buzdar AU, Smith TL, et al. Is breast cancer survival improving? Cancer 2004;100:44-52

- Osoba D, Slamon DJ, Burchmore M, et al. Effects on quality of life of combined trastuzumab and chemotherapy in women with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20:3106-3113

- Grabsch B, Clarke DM, Love A, et al. Psychological morbidity and quality of life in women with advanced breast cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Palliat Support Care 2006;4:47-56

- Facchini G, Caraglia M, Santini D, et al. The clinical response on bone metastasis from breast and lung cancer during treatment with zoledronic acid is inversely correlated to skeletal related events (SRE). J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2007;26:307-312

- Pavlakis N, Schmidt R, Stockler M. Bisphosphonates for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;3:CD003474

- Fassett DR, Couldwell WT. Metastases to the pituitary gland. Neurosurg Focus 2004;16:E8

- Morrow M, Goldstein L. Surgery of the primary tumor in metastatic breast cancer: closing the barn door after the horse has bolted? J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2694-2696

- Nadji M, Gomez-Fernandez C, Ganjei-Azar P, et al. Immunohistochemistry of estrogen and progesterone receptors reconsidered: experience with 5,993 breast cancers. Am J Clin Pathol 2005;123:21-27

- Possinger K. Fulvestrant: a new treatment for postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive advanced breast cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2004;5:2549-2558

- NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer, v2.2008. Available at http://www.nccn.org. [Last accessed 3 November 2009]

- Beslija S, Bonneterre J, Burstein H, et al. Second consensus on medical treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2007;18:215-225

- Wilcken N, Hornbuckle J, Ghersi D. Chemotherapy alone versus endocrine therapy alone for metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;2:CD002747

- Lin NU, Winer EP. Advances in adjuvant endocrine therapy for postmenopausal women. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:798-805

- Jazaeri AA, Maxwell GL, Rice LW. Hormones and human malignancies. In: Hoskins WJ, Perez CA, Young RC, et al., Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology, 4th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004:17

- Rugo HS. The breast cancer continuum in hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer in postmenopausal women: evolving management options focusing on aromatase inhibitors. Ann Oncol 2008;19:16-27

- Smith I, Chua S. Medical treatment of early breast cancer. IV: neoadjuvant treatment. BMJ 2006;332:223-224

- ATAC Trialists’ Group. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer 2003;98:1802-1810

- Rau KM, Kang HY, Cha TL, et al. The mechanisms and managements of hormone-therapy resistance in breast and prostate cancers. Endocr Relat Cancer 2005;12:511-532

- Ring A, Dowsett M. Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance. Endocr Relat Cancer 2004;11:643-658

- Yanagitani N, Shimizu Y, Kaira K, et al. Pulmonary toxicity associated with vinorelbine-based chemotherapy in breast cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 2008;35:1619-1621

- Philippin-Lauridant G, Thureau S, Ouvrier MJ, et al. Fatal hemoptysis in a patient with breast cancer treated with bevacizumab and paclitaxel. Ann Oncol 2008;19:1977-1978

- Erban JK, Lau J. On the toxicity of chemotherapy for breast cancer – the need for vigilance. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:1096-1097

- Welch HG, Fisher ES. Diagnostic testing following screening mammography in the elderly. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998;90:1389-1392

- Dang, C. Hormonal therapy: current status in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Continuing medical information. Available at http://www.cancernetwork.com/display-cme/article/10165/62333. [Last accessed September 20, 2010]

- D’Hoore W, Sicotte C, Tilquin C. Risk adjustment in outcome assessment: the Charlson comorbidity index. Methods Inf Med 1993;32:382-387

- Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Zhang HF, et al. Health care costs of adults treated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder who received alternative drug therapies. J Manag Care Pharm 2007;13:561-569

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Databases, tables & calculators by subject: Inflation and Prices. Available at http://www.bls.gov/data/#prices [Last accessed September 20, 2010]

- Lin DY. Linear regression analysis of censored medical costs. Biostatistics 2000;1:35-47

- Susan G. Komen Foundation. Recommended Treatments for Metastatic Breast Cancer. Available at http://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/RecommendedTreatmentsforMetastaticBreastCancer.html [Last Accessed September 20, 2010]

- Boccardo F, Rubagotti, A, Amoroso D, et al. Chemotherapy versus tamoxifen versus chemotherapy plus tamoxifen in node-positive, oestrogen-receptor positive breast cancer patients. An update at 7 years of the 1st GROCTA (Breast Cancer Adjuvant Chemo-Hormone Therapy Cooperative Group) trial. Eur J Cancer 1992;28:673-680

- Huober J, Fasching P, Paepke S, et al. Letrozole in combination with trastuzumab is superior to letrozole monotherapy as first line treatment in patients with hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (MBC) – Results of the eLEcTRA trial. Cancer Res 2009;69: Abstract nr 4094

- Giordano SH, Buzdar AU, Kau SC, Hortobagyi GN. Improvement in breast cancer survival: results from M. D. Anderson Cancer Center protocols from 1975–2000. Presented at ASCO, 2002 Abstract No: 212

- Rao S, Kubisiak J, Gilden D. Cost of illness associated with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2004;83:25-32

- Wai ES, Trevisan CH, Taylor SCM, et al. Health system costs of metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001;65:233-240

- Cocquyt V, Moeremans K, Annemans L, et al. Long-term medical costs of post-menopausal breast cancer therapy. Ann Oncol 2003;14:1057-1063

- Legorreta AP, Brooks RJ, Leibowitz AN, et al. Cost of breast cancer treatment: a 4-year longitudinal study. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:2197-2201

- Lin DY, Feuer EJ, Etzioni R, et al. Estimating medical costs from incomplete follow-up data. Biometrics 1997;53:419-434

- Bang H, Tsiatis AA. Estimating medical costs with censored data. Biometrika 2000;87:329-343

- Baser O, Gardiner JC, Bradley CJ, et al. Longitudinal analysis of censored medical cost data. Health Econ 2006;15:513-525

- Raikou M, McGuire A. Estimating medical care costs under conditions of censoring. J Health Econ 2004;23:443-470

- O'Hagan A, Stevens JW. On estimators of medical costs with censored data. J Health Econ 2004;23:615-625

- Young TA. Estimating mean total costs in the presence of censoring: a comparative assessment of methods. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23:1229-1242