Abstract

Purpose:

To assess rates and predictors of medication nonadherence and hospitalization among patients with bipolar I disorder.

Methods:

This was a retrospective cohort analysis of Medicaid patients who were aged ≥18 years, had ≥1 inpatient or ≥2 outpatient medical claims indicating bipolar I disorder (ICD-9-CM codes 296.0x–296.1x, 296.4x–296.7x), and filled ≥1 prescription for antipsychotic medication between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2006. Patients were followed for 1 year from the date of first (index) antipsychotic prescription. Patients were required to be continuously eligible for Medicaid without dual Medicare eligibility from 1 year before (baseline) through 1 year after (follow-up) index, and were required to receive ≥1 additional antipsychotic during follow-up. Descriptive statistics and predictors of medication nonadherence (medication possession ratio <0.8) and hospitalization were generated.

Results:

A total of 9410 patients met study eligibility criteria with a mean age of 38 years; 74% were female and 75% were white. Approximately 31% and 57% had baseline diagnoses of substance abuse and other psychiatric conditions, respectively. During follow-up, roughly 60% of patients were nonadherent and 40% of patients were hospitalized for any reason (37% psychiatric-related). Multivariate analysis showed that new antipsychotic starts, younger patients, those with a baseline concomitant substance abuse diagnosis, those taking a baseline antidepressant, and those with a baseline psychiatric hospitalization had significantly higher risk of nonadherence. Baseline psychiatric hospitalization, baseline substance abuse or other psychosis diagnosis, baseline use of an anxiolytic, anticholinergic, or anticonvulsant, and nonadherence to therapy in the follow-up period were significant predictors of increased risk of hospitalization.

Limitations:

This analysis did not attempt to evaluate the complex relationships among treatment type, adherence, hospitalization, and other variables.

Conclusions:

Study results showed that the risk of nonadherence is relatively high and confirmed that nonadherence is associated with a greater risk of hospitalization.

Introduction

Bipolar disorders afflict approximately 4.4% of the adult population, or 9 million people in the United StatesCitation1,Citation2, and bipolar I disorder has a lifetime prevalence ranging from 0.4% to 1.6% in community samplesCitation3. Bipolar disorders are characterized by manic and depressive statesCitation4,Citation5. In cases of bipolar I disorder, patients experience at least one manic or mixed episode, and may also experience a major depressive episodeCitation3. Symptoms of mania include grandiose ideas, increased energy and goal directed activity, irritability, agitation, distractibility, restlessness, impulsivity, and high-risk behavior. Patients with bipolar disorder experiencing mania may also encounter racing thoughts, strange or unusual ideas, or hallucinations. Symptoms of depression include feeling worried or empty for an extended length of time, loss of interest, feeling tired, difficulty concentrating or making decisions, restlessness, irritability, changes in eating and sleeping habits, and thoughts of death and suicide. Mixed episodes are defined as cycling between symptoms of a manic episode and symptoms of a major depressive episode.

Bipolar disorders are usually initially treated with mood stabilizers, such as lithium, and anticonvulsants; however, conventional (i.e., first-generation) and second-generation antipsychotic medications may be prescribed as monotherapy or in combination with mood stabilizers or anticonvulsants when symptoms are not controlledCitation6,Citation7. Nonadherence to therapy is common when patients are required to take medications on a long-term basis and is exacerbated by conditions such as bipolar disorder, which require continued and long-term use of a drugCitation8. Factors associated with poor adherence among patients with bipolar disorder include substance abuse disorder, disease condition denial, and adverse effects of treatmentsCitation6,Citation8,Citation9. Previous studies have found that patients with bipolar disorder (including bipolar I disorder) who are nonadherent to therapy also are more likely to experience relapse of symptoms and repeated hospitalizationsCitation10–13.

Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics were first introduced in the early 1970s in depot forms of the conventional antipsychotics, such as fluphenazine and haloperidol. LAI antipsychotics are thought to improve treatment adherence among patients with psychiatric conditions through confirmed medication delivery (injection vs. oral) and increased monitoring (routine office visits vs. pharmacy refills for acquiring medication)Citation14,Citation15, but little is known about their impact on treatment adherence in patients with bipolar disorder. It has been shown that patients with schizophrenia receiving LAI antipsychotics tend to be at least as adherent as they are when receiving oral medicationsCitation16. Further, one study found that patients with schizophrenia who were previously nonadherent to oral antipsychotics may be more adherent with LAI antipsychoticsCitation17.

Limited data are available on predictors of rates of medication nonadherence and on the relationship between nonadherence and hospitalizations among patients with bipolar disorder. Moreover, to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to report the predictors of medication nonadherence and hospitalization among patients with bipolar I disorder in a Medicaid population since the introduction of the newer second-generation LAI antipsychotics.

The goals of this retrospective database study were (1) to assess rates of medication nonadherence, hospitalization, and emergency room (ER) visits among patients with bipolar I disorder by type of antipsychotic treatment received; and (2) to examine predictors of medication nonadherence and assess the relationship between nonadherence and hospitalization.

Patients and methods

Overview

This claims-based, retrospective cohort analysis included Medicaid recipients who were not dually eligible for Medicare, who had at least one inpatient or two outpatient claims indicating bipolar I disorder, and who received an antipsychotic between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2006. Study patients were required to be continuously eligible for Medicaid benefits from 1 year before study entry through 1 year after study entry, and to have filled one additional prescription for an antipsychotic during the follow-up period (to ensure a treated population). Study measures included medication nonadherence (i.e., medication possession ratio, persistence, and maximum continuous gap in treatment), hospitalizations (psychiatric and all-cause), ER visits (psychiatric and all-cause), and payments per hospitalization or ER visit (psychiatric and all-cause). Multivariate logistic regression models were used to identify predictors of nonadherence, psychiatric-related hospitalization, and all-cause hospitalization.

Data source

This study was based on the eligibility data, medical claims data, and pharmacy claims data provided in the MarketScan (a registered trade name of Thomson Reuters) Multi-State Medicaid database. This database contained information about more than 16 million individuals pooled from multiple geographically dispersed states, including patients covered by Medicaid managed-care plans. Information was available for non-dually eligible patients (83.1% of the population) regarding inpatient, outpatient, and prescription drug claims. Data were separated into core files: an eligibility file, a medical claims detail file, and a pharmacy claims detail file.

The eligibility file contained data on patient-level demographics, monthly eligibility status, and monthly dual (Medicaid and Medicare) eligibility status. Data provided in the medical claims detail file included up to 15 diagnosis and procedure codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), service start and end dates, place of service, provider type, and payments (total gross payments to all providers). The pharmacy claims detail file provided prescription dispensing dates, national drug codes, quantity of drug dispensed, days supplied, and payment information.

Patient selection and follow-up

Patients were selected if they had at least one inpatient or two outpatient medical claims indicating a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder (ICD-9-CM codes: 296.0x, 296.1x, 296.4x, 296.5x, 296.6x, 296.7x) and filled at least one prescription for an antipsychotic between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2006; had continuous Medicaid benefits eligibility through the baseline period (1 year before the index date, as defined by the first antipsychotic prescription fill date) and follow-up period (1 year after the index date); were aged 18 years or older at index date; and had at least one additional antipsychotic prescription fill during the follow-up period. Medicare and Medicaid dually eligible patients were excluded.

Patients were assigned to one of five mutually exclusive study cohorts in a hierarchical fashion based on the type of antipsychotic treatment received during the follow-up period. Hierarchical assignment was used because most patients who received LAI antipsychotics also received oral medication resulting in small sample sizes of patients who received LAI antipsychotics alone. The LAI second-generation cohort included patients who received any LAI second-generation antipsychotic without regard to other antipsychotics received. In the LAI first-generation cohort, patients received any LAI first-generation antipsychotic and did not receive a LAI second-generation antipsychotic. The oral first- and second-generation cohort included those who received both oral first- and second-generation antipsychotics and received no LAI antipsychotics. The oral second-generation only cohort included patients who received oral second-generation antipsychotics only. Last, the oral first-generation only cohort included patients who received oral first-generation antipsychotics only.

The sample of antipsychotic users with bipolar I disorder was randomly split, and 50% of the population was used to conduct the analyses reported here. The remaining 50% was used in a separate analysis to validate the regression equations developed in this analysis, and results of that analysis will be presented in a separate publication.

Study measures

Patient demographics that were assessed included age (as of the index date), sex, and geographic region. Concomitant diagnoses of substance abuse (ICD-9-CM codes 303.xx–305.xx and V654.2), other psychotic conditions including dementia and schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM codes 290.xx–299.xx, excluding 296.0x, 296.1x, and 296.4x–296.7x), and selected concomitant medications (i.e., antidepressants, anticholinergics, mood-stabilizing agents [e.g., lithium], and anxiolytics) were assessed in the baseline period. A medication that could be considered both a mood stabilizer and an anticonvulsant (e.g., divalproex and carbamazepine) was classified as an anticonvulsant. Charlson comorbidities and the Deyo–Charlson Comorbidity scoreCitation18,Citation19, a measure of the overall burden of comorbidity on a patient, were also measured over the 12 months before the index date. The number of days of any antipsychotic treatment during baseline and the number of new starts were evaluated, with new starts defined as patients who did not receive any antipsychotic in the first 9 months (275 days) of the baseline (preindex) period.

Three alternative measures of medication adherence were assessed in the follow-up period. The medication possession ratio (MPR) was defined as the number of ambulatory days the patient received antipsychotic medication divided by the number of ambulatory days remaining in the period (i.e., from the index date through the follow-up period) after the first antipsychotic was dispensed. Patients with a MPR less than 0.8 were defined as nonadherent to therapy. Persistence was defined as the number of days between the first and last day receiving an antipsychotic divided by the number of days remaining in the period after the first antipsychotic was dispensed. Last, maximum gaps in therapy were defined as the maximum number of consecutive days between antipsychotics.

Psychiatric and all-cause hospitalizations were evaluated at the individual level (i.e., whether or not the patient had one or more hospitalizations) and at the overall level (i.e., the percentage of patients with one or more hospitalizations). Psychiatric hospitalizations were defined as all hospitalizations with a primary or secondary ICD-9-CM diagnosis in the range 290.xx–319.xx, whereas all-cause hospitalizations included all hospitalizations regardless of the diagnosis.

Similarly, the percentages of patients with one or more psychiatric and all-cause ER visits were studied in the follow-up period. Psychiatric visits were defined as all ER visits with a primary or secondary ICD-9-CM diagnosis in the range 290.xx–319.xx, whereas all-cause ER visits included all ER visits regardless of the diagnosis. Payments per visit for both psychiatric-related and all-cause hospitalizations and ER visits were also assessed.

Data analyses

Descriptive analyses were reported by treatment cohort on all demographic and clinical characteristics. Unadjusted analyses of medication nonadherence during the follow-up period were reported overall and by antipsychotic treatment cohort. Bivariate analyses of hospitalizations, ER visits, and payments for hospitalizations and ER visits were also reported by level of nonadherence (MPR <0.8 vs. MPR ≥0.8).

Multivariate logistic regressions were used to identify potential predictors of nonadherence and hospitalization (all-cause and psychiatric-related). Predictors included in the nonadherence model included patient age, concomitant diagnoses, use of concomitant medications, newly starting antipsychotic treatment, and antipsychotic cohort. Predictors in the models for hospitalizations included patient age, concomitant diagnoses, baseline psychiatric-related hospitalization, use of concomitant medications, newly starting antipsychotic treatment, and level of nonadherence. Interaction terms were not investigated. Significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

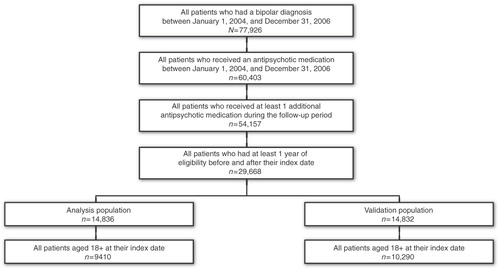

We initially identified 77,926 patients with at least one inpatient or two outpatient diagnoses of bipolar I disorder between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2006, with 60,403 receiving at least one antipsychotic during that period. Of those, 29,668 had at least one additional antipsychotic claim during the follow-up period and were eligible for benefits from 1 year before through 1 year after index. The sample was then evenly split, with 14,834 patients randomly selected for this analysis population, and the remainder used for a separate validation analysis to evaluate the regressions created (results will be presented in a separate publication). In the analysis population, the 9410 patients who were 18 years or older at their index date were retained for the final study sample (.

Over 80% of patients were in the oral second-generation only cohort (81%), with almost 10% in the oral first- and second-generation cohort, 4% in the LAI first-generation cohort, 2% in the oral first-generation only cohort, and 2% in the LAI second-generation cohort (). Average patient age (38 years) and the proportion of female patients (74%) were similar across study cohorts. The LAI antipsychotic cohorts included higher percentages of males and blacks than the oral medication cohorts. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (27%) and diabetes mellitus (14%) were the most prevalent comorbidities, whereas the mean (±standard deviation [SD]) Charlson score was relatively low (0.7 ± 1.2) and consistent across cohorts, likely reflecting the young age of the study population.

Table 1. Baseline and demographic characteristics of patients with bipolar I disorder.

Almost 31% and 57% of patients had substance abuse and other psychosis diagnoses in the baseline period, respectively, with rates of other psychoses considerably higher among those receiving LAI antipsychotics compared with those receiving oral medications only. In the baseline period, approximately 76% of patients received concomitant antidepressants, 63% received anticonvulsants, and 69% received mood stabilizers or anticonvulsants. Almost 40% of all study patients were newly starting antipsychotic therapy, with higher rates of new starts in the oral medication cohorts. Last, 36% of patients had a psychiatric-related hospitalization in the baseline period, with the highest rate in the LAI second-generation cohort (58%) and the lowest rate in the oral first-generation only cohort (21%).

Unadjusted analyses of medication nonadherence in the 12-month follow-up period found that the mean (±SD) MPR was 0.63 (±0.29) across all cohorts and that roughly 60% of patients were characterized as nonadherent to their medication, based on a MPR <0.80 (). By medication types, mean MPRs ranged from 0.57 for the oral first-generation only cohort to 0.74 for the LAI second-generation cohort, whereas nonadherence rates (MPR <0.80) ranged from 47% in the LAI second-generation cohort to 61% in the oral second-generation only cohort. Across all study cohorts, mean persistence was 0.85, ranging from 0.79 for the oral first-generation only cohort to 0.94 for the LAI second-generation cohort. The mean (±SD) maximum consecutive gap in treatment was 50.0 (±62.1) days overall, and the average maximum gaps ranged from 42.6 days for the LAI second-generation cohort to 58.7 days for the oral first- and second-generation cohort.

Table 2. Medication adherence in the follow-up period in patients with bipolar I disorder.

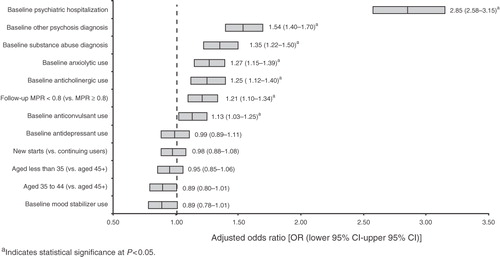

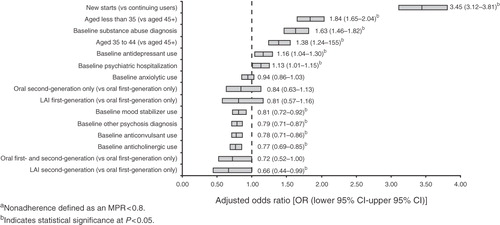

Based on multivariate logistic regression, the significant predictors of an increased risk of nonadherence included newly starting antipsychotic treatment, younger patient age, baseline substance abuse diagnosis, baseline psychiatric hospitalization, and baseline antidepressant use (). In contrast, patients who received LAI second-generation antipsychotics or both oral first- and second-generation antipsychotics (vs. oral first-generation medications only) had a lower likelihood of nonadherence. Other significant predictors of a lower risk of nonadherence included a baseline diagnosis of other psychosis and baseline use of a mood stabilizer, anticholinergic, or anticonvulsant.

Figure 2. Adjusted odds of medication nonadherence among patients with bipolar I disorder treated with antipsychotic medicationsa. LAI, long-acting injectable; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; MPR, medication possession ratio.

Overall, nearly 67% of patients had an ER visit for any reason during the follow-up period (), whereas 29% of patients had a psychiatric-related ER visit. Patients classified as nonadherent were more likely to have an ER visit for any reason (73 vs. 57%) or to have a psychiatric-related ER visit (32 vs. 25%) than those classified as adherent. The mean (±SD) payments were $158 (±$218) per all-cause ER visit and $256 (±$416) per psychiatric-related ER visit (data not shown). Almost 40% of all patients were hospitalized for any reason during the follow-up period, whereas 37% of patients were hospitalized with a psychiatric-related diagnosis. Patients who were classified as nonadherent were more likely to be hospitalized for any reason (42 vs. 37%) or have a psychiatric-related admission (38 vs. 35%) than those classified as adherent. The mean (±SD) payments were $6986 (±$10,374) per all-cause hospitalization and $6916 (±$10,288) per psychiatric-related hospitalization (data not shown).

Table 3. Percentage of hospitalizations and emergency room visits in the follow-up period in patients with bipolar I disorder.

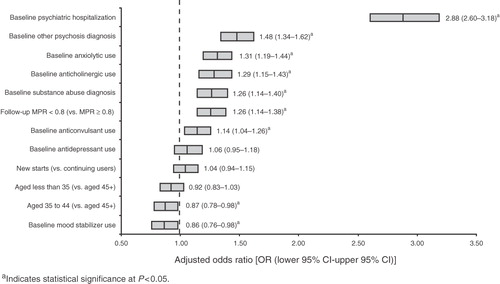

Based on multivariate logistic regression, the significant predictors of an increased risk of all-cause and psychiatric-related hospitalization included a baseline psychiatric hospitalization; baseline substance abuse or other psychosis diagnosis; baseline use of an anxiolytic, anticholinergic, or anticonvulsant; and nonadherence to therapy in the follow-up period (p < 0.05) ( and ). There were no significant predictors of a decreased risk of psychiatric-related hospitalization, but patients aged 35–44 years (vs. those older than 45 years) and those with baseline use of a mood stabilizer were significantly less likely to have an all-cause hospitalization (p < 0.05).

Discussion

This retrospective analysis of multistate Medicaid data found that adherence to antipsychotic treatment was relatively poor, with almost 60% of patients being nonadherent (MPR <0.8) to antipsychotic therapy. The analysis identified several predictors for a higher risk of antipsychotic nonadherence, including newly starting therapy, younger age, baseline concomitant substance abuse diagnosis, baseline antidepressant use, and baseline psychiatric hospitalization. Conversely, those with a baseline diagnosis of other psychoses; baseline use of a mood stabilizer, anticholinergic, or anticonvulsant; and those receiving LAI second-generation or oral first- and second-generation antipsychotics together were found to have a significantly lower likelihood of nonadherence to therapy. Hospitalizations were found to be fairly common over the 1-year follow-up period, with approximately 40% of patients being hospitalized. Significant predictors of an increased risk of psychiatric-related or all-cause hospitalization included baseline substance abuse or other psychosis diagnoses; baseline anxiolytic, anticholinergic, or anticonvulsant use; baseline psychiatric hospitalization; and nonadherence to antipsychotic therapy in the follow-up period.

The authors believe that this is the first large database analysis to evaluate predictors of medication nonadherence and hospitalization among patients with bipolar I disorder in a Medicaid population since the introduction of the newer LAI second-generation antipsychotics. The results of this analysis are comparable to those reported in other database studies evaluating similar adherence measures among patients with bipolar disorders; however, these studies did not include LAI second-generation antipsychotics (only one study included LAI first-generation medications) and were not specific to bipolar I disorder, as described below.

Hassan et al. reported that the overall mean MPR for oral second-generation antipsychotics (olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine) and oral first-generation antipsychotics was 0.63, the same as the current analysis reports, despite slight differences in treatment cohorts. They did not report overall adherence rates based on MPR, but they found that adherence was higher in users of second-generation antipsychotics than in users of first-generation antipsychoticsCitation6. In another study of veterans with bipolar disorder in the Veterans Affairs National Psychosis Registry, Sajatovic et al. found 52% were fully adherent (MPR ≥0.8) to oral first- and second-generation antipsychotics, but this study did not consider the effects of LAI antipsychoticsCitation20. A database study of commercially insured patients with bipolar disorder reported only 15.8% were adherent (MPR ≥0.8) to first- and second-generation antipsychotics combinedCitation21, which is considerably lower than the rate found in the current analysis; however, that study analyzed all patients with bipolar disorder in a commercial population, had a younger average patient age, and did not include only ambulatory days in creating the MPR.

In addition to describing rates of nonadherence with oral antipsychotics, a few previous studies have identified important predictors of nonadherence. Similar to the results of the current analysis, Sajatovic et al. found that younger age and comorbid substance abuse were associated with increased risk of nonadherenceCitation22. They found that minority ethnicity and homelessness, variables that were not included in the current model, were also associated with higher rates of nonadherence. Additionally, past studies have presented odds ratio estimates for nonadherence as a predictor of hospitalization among patients with bipolar disorders receiving oral antipsychotics. Similar to findings in the current analysis, Lage et al. found that in a commercial population, a MPR ≥0.75 was associated with a lower risk of all-cause hospitalization (OR: 0.85) and a MPR ≥0.80 was associated with lower risk of psychiatric hospitalization (OR: 0.80)Citation21. A second commercial database study found patients with bipolar disorder with a MPR ≥0.75 had a significantly lower risk of all-cause (OR: 0.72) and psychiatric-related (OR: 0.76) hospitalizationCitation10. Gianfrancesco et al. found that predictors of psychiatric hospitalizations in commercially insured patients with bipolar disorder showing predominantly manic or mixed symptoms were disease severity, presence of other psychoses, substance abuse, and switching from a previous antipsychoticCitation23.

This analysis was subject to several limitations. Bipolar I disorder diagnoses were not verified by medical chart reviews. Other variables (e.g., family involvement, living situation, denial of illness), which have been shown to affect medication adherence, could not be assessed because they were unavailable in claims databases. Additionally, findings from the current analysis may not apply to non-Medicaid populations or to those dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. This analysis may overestimate adherence because treated days could not be confirmed among patients receiving oral therapies; information was available only for the prescriptions filled, not medications actually taken. Moreover, because medication cohorts were created in a hierarchical fashion, adherence to LAI antipsychotic therapy may also reflect the influence of oral medications. Similarly, patients in the LAI second-generation cohort had the highest unadjusted hospitalization rate (data not shown), suggesting that this type of medication is often administered to patients requiring hospitalization and possibly those with previously poor adherence. Although the requirement in the current analysis that patients remain eligible for Medicaid benefits during the study period was necessary for tracking, it may have biased this sample to include patients more likely to remain adherent. Finally, this analysis was cross-sectional and did not attempt to evaluate the complex nature of the relationships among treatment type, adherence, hospitalization, and other variables; future work to disentangle this interaction is warranted.

Conclusion

In this large Medicaid population, we found that the risk of nonadherence was lower among older patients; continuing antipsychotic users; those without a baseline substance abuse diagnosis or baseline use of antidepressant; those receiving a baseline mood stabilizer, anxiolytic, anticholinergic, or anticonvulsant; and those receiving LAI second-generation or oral first- and second-generation antipsychotics together. Further, after adjusting for baseline and demographic characteristics, the findings of the current analysis confirm that nonadherence is associated with a greater risk of hospitalization. By identifying factors associated with nonadherence among varying medication types and exploring the relationship between nonadherence and hospitalization, the results of this analysis may help to identify patient characteristics that are associated with increased risk of nonadherence and hospitalization for patients with bipolar I disorder. These results may be useful to formulary decision makers and to physicians who treat these patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which provided funding to Boston Health Economics, Inc, for the study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

K.L., J.M., and J.K. received research funding from Johnson & Johnson Research and Development, LLC. E.M. and J.C.C. are employees of the sponsor, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and Johnson & Johnson shareholders. S.A. was an outcomes research fellow at Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, when the analysis was conducted.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Lauren Rodriguez at Boston Health Economics, Inc, for assistance with the manuscript.

This work was presented in part at the 15th Annual International Meeting of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research; May 15–19, 2010; Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

References

- Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Wang PS. Prevalence, comorbidity, and service utilization for mood disorders in the United States at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2007;3:137-158

- Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:543-552

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, 1994

- National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar disorder. National Institutes of Health 2009; Available at: URL: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/bipolar-disorder/index.shtml. Accessed March 16, 2010

- Buckley PF. Update on the treatment and management of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. CNS Spectr 2008;13(Suppl 1):1-10

- Hassan M, Madhavan SS, Kalsekar ID, et al. Comparing adherence to and persistence with antipsychotic therapy among patients with bipolar disorder. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:1812-1818

- Moller HJ, Nasrallah HA. Treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(Suppl 6):9-17

- Berk L, Hallam KT, Colom F, et al. Enhancing medication adherence in patients with bipolar disorder. Hum Psychopharmacol 2010;25:1-16

- Scott J, Pope M. Nonadherence with mood stabilizers: prevalence and predictors. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:384-390

- Hassan M, Lage MJ. Risk of rehospitalization among bipolar disorder patients who are nonadherent to antipsychotic therapy after hospital discharge. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2009;66:358-365

- Scott J, Pope M. Self-reported adherence to treatment with mood stabilizers, plasma levels, and psychiatric hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:1927-1929

- Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK. Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:805-811

- Depp CA, Moore DJ, Patterson TL, et al. Psychosocial interventions and medication adherence in bipolar disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2008;10:239-250

- Love RC. Strategies for increasing treatment compliance: the role of long-acting antipsychotics. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2002;59(Suppl 8):S10-S15

- McEvoy JP. Risks versus benefits of different types of long-acting injectable antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:15-18

- Keks NA, Ingham M, Khan A, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone v. olanzapine tablets for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Randomised, controlled, open-label study. Br J Psychiatry 2007;191:131-139

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Ascher-Svanum H. Treatment of schizophrenia with long-acting fluphenazine, haloperidol, or risperidone. Schizophr Bull 2007;33:1379-1387

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-383

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613-619

- Sajatovic M, Bauer MS, Kilbourne AM, et al. Self-reported medication treatment adherence among veterans with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:56-62

- Lage MJ, Hassan MK. The relationship between antipsychotic medication adherence and patient outcomes among individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder: a retrospective study. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2009;8:7

- Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow FC, et al. Treatment adherence with antipsychotic medications in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2006;8:232-241

- Gianfrancesco FD, Sajatovic M, Rajagopalan K, et al. Antipsychotic treatment adherence and associated mental health care use among individuals with bipolar disorder. Clin Ther 2008;30:1358-1374