Abstract

Objectives:

Gastrointestinal (GI) blood loss is a common medical condition which can have serious morbidity and mortality consequences and may pose an enormous burden on healthcare utilization. The purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review to evaluate the impact of upper and lower GI blood loss on healthcare utilization and costs.

Methods:

We performed a systematic search of peer-reviewed English articles from MEDLINE published between 1990 and 2010. Articles were limited to studies with patients ≥18 years of age, non-pregnant women, and individuals without anemia of chronic disease, renal disease, cancer, congestive heart failure, HIV, iron-deficiency anemia or blood loss due to trauma or surgery. Two reviewers independently assessed abstract and article relevance.

Results:

Eight retrospective articles were included which used medical records or claims data. Studies analyzed resource utilization related to medical care although none of the studies assessed indirect resource use or costs. All but one study limited assessment of healthcare utilization to hospital use. The mean cost/hospital admission for upper GI blood loss was reported to be in the range $3180–8990 in the US, $2500–3000 in Canada and, in the Netherlands, the mean hospital cost/per blood loss event was €11,900 for a bleeding ulcer and €26,000 for a bleeding and perforated ulcer. Mean cost/ hospital admission for lower GI blood loss was $4800 in Canada, and $40,456 for small bowel bleeding in the US.

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest that the impact of GI blood loss on healthcare costs is substantial but studies are limited. Additional investigations are needed which examine both direct and indirect costs as well as healthcare costs by source of GI blood loss focusing on specific populations in order to target treatment pathways for patients with GI blood loss.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a major, clinically significant medical conditionCitation1,Citation2. Blood loss can originate from either the upper GI tract (esophagus or stomach) or the lower GI tract (small or large intestines)Citation3,Citation4. GI blood loss can result in significant morbidity and mortalityCitation5 and may impose a substantial burden on healthcare resourcesCitation3. In Westernized countries, the annual incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding is estimated to be between 100 and 200 cases per 100,000 and between 20 and 30 cases per 100,000 for lower gastrointestinal bleeding and the estimated mortality rates range from 6% to 10% for upper GI bleeding and from 2% to 4% for lower GI bleeding respectivelyCitation3,Citation6–8.

Acute GI bleeding frequently results in hospitalization requiring urgent diagnostic workup and management. Various laboratory tests and diagnostic procedures such as imaging, endoscopy, enteroscopy, and colonoscopy may be required to identify the source of blood loss for appropriate management. Among patients with acute small bowel bleeding, previous research suggests that outcomes may be significantly worse with higher morbidities, longer hospital stays, and higher health expenditures compared to patients with upper GI bleedingCitation9. Additionally, in about 25% of patients with acute lower GI bleeding who undergo colonoscopy, no identifiable source of GI blood loss is found and additional diagnostic procedures are needed to help localize the source of bleedingCitation10,Citation11.

It is estimated that upper GI bleeds impose $2.5 billion in annual healthcare costs in the USCitation12. Several studies have reported that between 20% and 40% of the total costs of treatment for GI events may be attributed to the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)Citation13,Citation14. In fact, NSAIDs are among the most frequently prescribed medications in the US with more than 60 million Americans using NSAIDs which contributes to the high economic burden due to clinically significant GI events associated with the use of NSAIDsCitation15,Citation16. Although studies have been conducted to assess the economic burden associated with GI blood loss, there has been no synthesis of current evidence in this area and most of these studies have examined primarily upper GI blood loss. The purpose of this study was to systematically review current research on the impact of both upper and lower GI blood loss on healthcare resource utilization and costs in order to target treatment pathways for patients with GI blood loss.

Methods

Search strategy

The MEDLINE database was searched to identify studies published between January 1, 1990 through September 30, 2010 using key words for blood loss and combining them with search terms for measures of healthcare resource utilization and costs. The MESH headings used for economic outcomes included: economic outcome, medical resource utilization, health resource utilization, medical expenditure, and cost utility. The search strategy was supplemented with a hand-search of the bibliographies of retrieved articles and by searching MEDLINE for relevant articles published after completion of the original search.

Search terms

Study selection criteria

The search was limited to English language articles in study populations of adults at least 18 years of age and women who were not pregnant. Articles were excluded if blood loss was not likely to be of GI origin or if hemoglobin levels or blood loss had another etiology (i.e., cancer, renal disease, congestive heart failure, HIV/AIDS, anemia, trauma or surgery). A two-phase review process was used to assess relevance of publications. In phase one, the titles and abstracts identified in the search strategy were screened; in phase two, the manuscripts identified for further assessment underwent full article review and data abstraction.

Two researchers (D.P., X.L.) independently reviewed and graded the abstracts utilizing a modified Cochrane Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) criteriaCitation17,Citation18 to assess article quality. There was about 85% concordance between the two researchers in reviewing the abstracts and discordant quality assessments were resolved through additional discussion.

Data extraction

One of the researchers (X.L.) independently read and extracted outcome data from all eligible studies using a standard form. For each study, the following data were extracted: study design, sample size, country where the research was conducted, setting, time frame, and source of GI bleeding. During abstraction, the table was reviewed for accuracy, completeness, and adherence to review methodology. Once abstraction was complete, the evidence table and original articles were independently reviewed by a second investigator (DP). Inclusion in the systematic review was based on a combination of the article’s relevance to the study objective, whether it met inclusion criteria, and whether it was methodological sound.

Results

Study selection

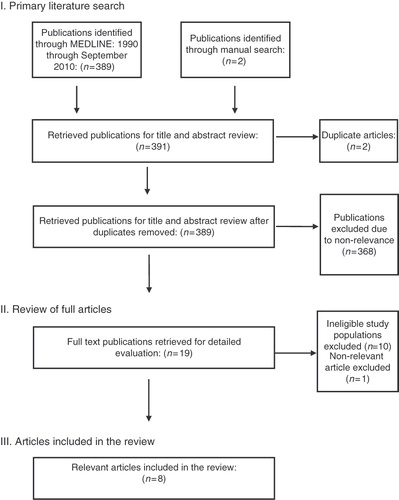

The initial search identified 389 articles including two articles identified by manual search and two duplicates (see ). Of the 389 articles selected, 368 articles were excluded due to non-relevance to the topic. The remaining 19 articles underwent full text review. Eleven of the articles were excluded due to ineligible study populations (n = 10) or non-relevance (n = 1). A total of eight articles were included in this review.

Study characteristics

summarizes major characteristics of the studies included in the review. Five studies examined upper GI blood lossCitation5,Citation19–21,Citation23, one assessed lower GI blood lossCitation22, one compared small bowel blood loss to colonic and upper GI blood lossCitation9, and the most recent study compared upper and lower GI blood lossCitation24. All but one study included patients who were over 50 years of ageCitation9,Citation19–24. In the study including younger individuals, 92% of the patients were less than 65 years of age and 13% were less than 35 years of ageCitation5.

Table 1. Summary of study characteristics and research design of included studies.

Six of the studies included small sample sizes (<160 patients)Citation9,Citation19–23 whereas the two most recent studies included larger study populationsCitation5,Citation24. Cryer et al. studied 9033 patients with upper GI blood loss and 579,018 patients with no record of GI blood loss who were enrolled in a large, US managed healthcare planCitation5. Whelan et al. also included a larger sample of 367 patients (lower GI blood loss = 187 and upper GI blood loss = 180)Citation24.

Four of the studies included were from the USCitation5,Citation9,Citation19,Citation24, three from CanadaCitation20–22, and one from the NetherlandsCitation23. Seven of the studies included patients from clinical settings, either a single medical center or several academic or community hospitals. Identification of patients with GI bleeding was based on administrative databases and/or medical records. All studies included patients with GI bleeding. Cryer et al. also compared resource utilization and costs of patients with upper GI bleeding to resource utilization and costs of patients with no upper GI bleeding from the same health planCitation5.

Health resource use

summarizes the major findings on the impact of upper and lower GI blood loss on resource utilization and costs. All of the studies evaluated resource utilization related to medical care. When assessing healthcare resource utilization, seven of the eight studies limited their assessments to resources used during hospitalization. In addition to health resource utilization during hospitalization, one study investigated other sources of medical resource utilization such as office-based visits, outpatient visits, and prescription medication useCitation5.

Table 2. Summary of studies included in the review.

Hospital resource utilization assessment varied among the different studies. In general, studies showed that hospital resource use for patients with upper or lower GI blood loss was substantial. The duration of hospitalization ranged from 4.3 to 18.2 days, with small bowel bleeding incurring the longest hospital stays (18.2 days) and upper GI bleeding associated with the shortest hospitalization (4.3 days). Endoscopy procedures were commonly conducted with 42–81% of patients undergoing these procedures during their admission. Blood transfusions were frequently provided and mean units of blood transfused ranged from 1.64 to 6 units. Laboratory tests such as complete blood counts (CBC) and coagulation profiles were performed during hospitalization and, in one study, about seven complete blood counts (CBC) and one coagulation profile was performed per patientCitation22. Between 3 and 10% of patients also underwent surgery during hospitalization.

Analyzing hospital resource use by source of blood loss, Prakash et al.Citation9 found that patients with acute small bowel bleeding required a significantly greater number of diagnostic procedures (p < 0.001), blood transfusions (p < 0.001), and had longer hospitalizations (p < 0.05) compared to patients experiencing colonic or upper GI bleeding.

GI blood loss was also associated with additional healthcare resource utilization unrelated to the hospitalization for the GI blood loss. Cryer et al. reported that 84.5% of patients had ambulatory visits and about 80% of patients had prescription refills related to upper GI bleeding during 12 months following the admission date of the first hospitalization for the upper GI bleeding eventCitation5. They also found that about 39% of patients underwent additional diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and that approximately 54% of patients had laboratory tests related to upper GI bleeding during the 12-month follow-up periodCitation5. When compared to the patients without upper GI bleeding, patients with upper GI bleeding experienced significantly higher (p < 0.0001) 12-month health-resource utilizationCitation5.

Healthcare costs

also summarizes findings on the impact of upper or lower GI blood loss on costs. Hospital costs for GI blood loss were substantial. In the Netherlands, mean hospital costs per blood loss event was €11,900 for a bleeding ulcer and €26,000 for a bleeding and perforated ulcer (1 euro = 1.14 US$)Citation23. In Canada, mean costs per hospital admission was 2953 Canadian dollars (1997 Canadian $) for upper GI blood lossCitation21 and about 4800 Canadian dollars for lower GI blood lossCitation22. In the USA, mean costs per hospital admission for upper GI blood loss ranged from US$3180 to US$8990Citation9,Citation19. Prakash and colleagues found that the cost of small bowel bleeding incurred much higher hospital costs than colonic bleeding ($40,456 vs. 9732) or upper GI bleeding ($40,456 vs. 8990) (1998 US$)Citation9.

Cryer et al. reported that the mean inpatient upper GI-related cost for the 12-month period following a GI hospitalization was $12,259 (1999–2003 US$). They also reported that the upper GI-related costs, 12 months following hospital admission for GI bleeding, were $1221 for ambulatory visits, $195 for emergency room visits, and $558 for medicationCitation5. In addition, Cryer et al. reported that patients with upper GI bleeding experienced significantly greater total healthcare expenditures during the 12-month period following the initial upper GI bleeding hospitalization as compared to the patients without upper GI bleeding. The total healthcare costs incurred over the hospitalization and the subsequent 12 months was $20,405 for patients who were hospitalized for upper GI bleeding, compared to $3652 for patients without upper GI bleedingCitation5. For those patients with upper GI bleeding, the majority of total healthcare costs were due to inpatient hospitalizations (64% of total costs) and ambulatory services (20% of total costs)Citation5.

Several studies also examined healthcare resource utilization or costs by patient subgroups. Age was examined in relation to healthcare resource utilization since older age is associated with upper GI blood loss and approximately 40% of upper GI blood loss patients are 60 years of age or olderCitation5. Marshall et al.Citation20,Citation21 found that older age was a predictor of total increased cost as well as length of hospital stay. Whelan et al. also reported that age was significantly associated with a difference in rates of upper versus lower GI bleeding with lower GI bleeding patients more likely to be older (p < 0.001) and female (p = 0.01) but did not note any differences in patterns of resource utilizationCitation24. Comay et al. reported that, in addition to older age, comorbidities, particularly coronary artery disease, were independent predictors of increased cost (p < 0.05, R2 = 0.109)Citation22.

Discussion

The small number of studies that met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review demonstrates that there is limited literature on the impact of GI bleeding on healthcare resource utilization and costs. Our review suggests that both upper and lower GI blood loss have a substantial impact on health resource use and healthcare costs, particularly among older patients.

The majority of the studies included in this review focused on healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with hospitalization for a GI bleed. While future studies should consider other sources of health resource use and costs, the findings suggest that hospitalizations and their associated costs are a major consequence of upper or lower GI blood loss. Additionally, one study that explored costs beyond those related to hospitalizations found that, while hospitalizations contributed a large proportion to total healthcare costs, substantial costs were accrued through the costs of prescription medication as well as outpatient and emergency room visits in the year immediately following hospitalizationCitation5.

Given the high costs of hospitalization for patients with GI bleeding, economic benefits may be gained from successful management of patients with GI bleeding. While hospitalization for GI blood loss may be due to various reasons, as previously mentioned, use of NSAIDs is a major contributor since the use of NSAIDs substantially increases the risk of GI complicationsCitation25–27. Current recommendations for NSAIDs use is therefore important to assist in preventing avoidable hospitalizations associated with GI blood loss. Based on current recommendations, should an NSAID be needed (and the patient is at low risk for toxicity), the lowest effective dose of the least expensive agent should be considered as first line therapyCitation28. For patients who are at high risk of GI bleeding, use of COX-2 inhibitors or concomitant use of NSAIDS with gastroprotective agents has been recommendedCitation29.

The findings from this review that small bowel bleeding incurs about three times the hospital costs compared to colonic and upper GI bleeding indicates a need for better awareness, identification, prevention, and management of this condition. Moreover, the site of bleeding is not always clear in a significant proportion of patients who present with GI bleedingCitation24. It is therefore important to accurately identify early the source of bleeding, when possible, in order to reduce the number of procedures, costs, length of stay, and discomfort to the patients.

Our results suggest that studies examining the impact of GI blood loss on economic outcomes are currently limited. Except for two studies published in 2010Citation5,Citation24, all the other studies were more than 5 years old and the data used for each of the studies were not recent, with the latest data from 2003. There are several areas that future studies on the economic impacts of upper or lower GI blood loss should address. Most of the studies included in this review only examined direct healthcare resource utilization and costs incurred during hospitalization for a GI blood loss event. Only one study demonstrated that significant costs were accrued after the index hospitalizationCitation5. Furthermore, studies included in this review varied by sample size, were mainly limited to clinical settings with one or several participating sites, and differed by country of origin. Study findings may therefore be difficult to generalize to other populations. The one study which included members of a managed-care planCitation5, had findings limited to a commercially insured population and results therefore may not be generalizable to members of other health plans or publicly insured or uninsured populations.

There are several limitations in this review which should be addressed. First, we only searched for articles in PubMed and references indexed only in other databases may have been missed. Second, only articles in English were included and relevant references published in other languages may have been excluded. Previous research, however, has found that restricting reviews to English language publications does not introduce systematic biasCitation30. Finally, while direct comparisons of included studies may be limited due to differences in healthcare delivery systems and currencies between countries, the current review demonstrates that the impact of upper or lower GI blood loss on healthcare utilization and costs are substantial.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first review to summarize the literature on the impact of both upper and lower GI blood loss on healthcare resource utilization and costs. Substantial healthcare utilization and costs were associated with hospitalizations for both upper and lower GI bleeding. As a result of the vast numbers of patients who take NSAIDs and the clinically significant GI events associated with NSAIDs use, these complications remain a significant public health concern. Additional economic studies are warranted which assess direct and indirect costs of upper and lower GI blood loss and healthcare resource utilization by source of blood loss and for different populations to further an understanding of the effect of preventive use and changes in prescribing practices.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

D.R.P. was a paid consultant to Pfizer in connection with the development of this manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

X.L. and A.R.A, are full-time employees of Pfizer, Inc. and J.J.J. was a pre-doctoral fellow at Pfizer, Inc until May 2009, at the time when the study was initiated.

Acknowledgments

There is no assistance in the preparation of this article to be declared.

References

- Velayos FS, Williamson A, Sousa KH, et al. Early predictors of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and adverse outcomes: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:485-90

- Quirk DM, Barry MJ, Aserkoff B, et al. Physician specialty and variations in the cost of treating patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology 1997;113:1443-8

- Longstreth GF. Epidemiology of hospitalization for acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 1995;90:206-10

- Cagir B. Lower GI bleeding, surgical treatment. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/195246-overview. Accessed 11/12/2010

- Cryer BL, Wilcox CM, Henk HJ, et al. The economics of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a US-managed care setting: a retrospective claims-based analysis. J Med Econ 2010;3:70-7

- Wilcox C M, Cryer BL, Henk HJ, et al. Mortality associated with gastrointestinal bleeding events: comparing short-term clinical outcomes of patients hospitalized for upper GI bleeding and acute myocardial infarction in a US managed care setting. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2009;2: 21-30

- Wilcox CM, Clark WS. Causes and outcome of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding: the Grady Hospital experience. South Med J 1999;92:44-50

- Yavorski RT, Wong RK, Maydonovitch C, et al. Analysis of 3,294 causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding military medical facilities. Am J Gastroenterol 1995;90:568-73

- Prakash C, Zucherman GR. Acute small bowel bleeding: a distinct entity with significantly different economic implications compared with GI bleeding from other locations. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;58:330-5

- Zuckerman GR, Prakash C. Acute lower intestinal bleeding. Part I: clinical presentation and diagnosis. Gastrointest Endosc 1998;48:606-16

- Zuckerman GR, Prakash C. Acute lower intestinal bleeding. Part II: Etiology, therapy, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;49:228-38

- Laine L, Peterson WL. Bleeding peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med 1994;331:717-27

- Champion G, Feng PH, Azuma T, et al. NSAID-induced gastrointestinal damage: epidemiology, risk and prevention with an evaluation of the role of misoprostol: an Asian-Pacific perspective and consensus. Drugs 1997;53:6-19

- Singh G, Ramey DR, Morfeld D, et al. Gastrointestinal tract complications of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective observational cohort study. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:1530-6

- Dai C, Stafford RS, Alexander GC. National trends in cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor use since market release: non-selective diffusion of a selectively cost-effective innovation. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:171-7

- Graham DY, Chan FK. NSAIDs, risks, and gastroprotective strategies: current status and future. Gastroenterology 2008;134:1240-6

- Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. Interpreting results and drawing conclusions. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (eds), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.0, Chapter 12 (updated February 2008). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org

- Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations BMJ 2004;328:1490

- Richter JM, Wang TC, Fawaz K, et al. Practice patterns and costs of hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol 1991;13:268-73

- Marshall JK, Collins SM, Gafni A. Prediction of resource utilization and case cost for acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage at a Canadian Community Hospital. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:1841-6

- Marshall J, Collins S, Gafini A. Demographic predictors of resource utilization for bleeding peptic ulcer disease: The Ontario GI Bleed Study. J Clin Gastroenterol 1999;29:165-70

- Comay D, Marshall JK. Resource utilization for acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: The Ontario GI Bleed Study. Can J Gastroenterol 2002;16: 677-82

- De Leest HTJI, Van Dieten HEM, Van Tulder MW, et al. Costs of treating bleeding and perforated peptic ulcers in the Netherlands. J Rheumatol 2004;31:788-91

- Whelan CT, Chen C, Kaboli P, et al. Upper versus lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a direct comparison of clinical presentation, outcomes, and resource utilization. J Hosp Med 2010;5:141-7

- Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation 2008;118:1894-909

- Graham DY, Chan FK. NSAIDs, risks, and gastroprotective strategies: current status and future. Gastroenterology 2008;134:1240-6

- Bjarnason I, Hayllar J, MacPherson AJ, et al. Side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the small and large intestine in humans. Gastroenterology 1993;104:1832-47

- American College of Rheumatology ad hoc Group on Use of Selective and Nonselective Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs. Recommendations for use of selective and nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an American College of Rheumatology white paper. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1058-73

- Schnitzer TJ. Proceedings from the Symposium “The Evolution of Anti-Inflammatory Treatments in Arthritis: Current and Future Perspectives” Update of ACR Guidelines for Osteoarthritis: Role of the Coxibs. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;23(4S):S24-30

- Morrison A, Moulton K, Clark M, et al. English language restriction when conducting a systematic review-based-meta-analysis: systematic review of published studies. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, 2009