Abstract

Objective:

It is hypothesised that the presence of ocular, in addition to nasal, symptoms among patients with allergic rhinitis (AR) results in poorer quality of life, reduced work productivity and increased resource utilisation. This study investigated the impact on quality of life, burden of illness and healthcare resources among 1640 AR patients.

Methods:

Data were drawn from an observational cross-sectional study of consulting patients undertaken in May/June 2008 in four European countries. Doctors provided records for the next four to five patients presenting with AR who filled out a self-completion survey which included the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Allergic Specific Questionnaire (WPAI:AS), the Mini Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (RQOLQ) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Propensity scoring allied to regression-type analysis was used to assess the extra burden associated with ocular symptoms utilising two comparison groups (patients with nasal-only symptoms versus those with nasal and ocular symptoms). The analysis controlled for differences between the groups on confounding variables age, gender, smoking status and co-morbidities. The analysis was conducted twice, once controlling for differences between the groups in nasal severity and once without, recognising that it is not clear whether or not increased nasal severity symptoms are naturally associated with ocular symptoms. The severity of ocular symptoms as opposed to their presence alone was also assessed on outcome measures using regression type methods.

Results:

A total of 1009 patient records met the inclusion criteria, of whom 69% presented with both ocular and nasal symptoms. The results show that the presence of ocular symptoms reduces quality of life, reduces work productivity and increases resource utilisation irrespective of whether differences in severity of nasal symptoms are accounted for between the comparison groups. Patients with nasal and ocular symptoms require more healthcare consultations. All work-related domains were statistically different, with the presence of ocular symptoms associated with greater impact on work hours missed and impairment while working. For each of the above this was the case regardless of whether or not adjustment was made for nasal severity (both p < 0.05). Patients with nasal and ocular symptoms also record an additional half a day more time off work in the last 3 months as a result of AR (nasal severity unadjusted or adjusted, both p < 0.05). Clinically meaningful differences were found in overall quality of life score as represented by RQLQ, with a mean score increase of 0.6 (nasal severity unadjusted) and 0.5 (nasal severity adjusted) associated with the presence of ocular symptoms (both p < 0.05). With regard to sleep quality, the presence of ocular symptoms was associated with a mean increase in PSQI of 1 when no adjustment was made for nasal severity (p < 0.05). When nasal severity was adjusted for, no significant difference was observed. Similarly, for the number of prescribed medications, when no adjustment was made for nasal severity, patients with ocular symptoms were observed to receive a significantly higher number of AR drugs (+0.19, p < 0.05) whereas with nasal severity adjusted for the difference was +0.17 which was not significant. In addition, with the exception of the number of AR drugs prescribed, for all outcome variables, the severity of ocular symptoms, and not just their presence, had a detrimental impact on the outcome.

Limitations:

Since patients were recruited via the physician, the study aim was to represent the consulting population. In addition, it cannot be fully excluded that the likelihood for an individual patient to complete a questionnaire is influenced by differences in patient typology compared with those patients who chose not to complete. Given the geographical dispersion of the sample patients, it may be reasonable to assume possible differences in the intensity of the AR season based on latitude.

Conclusion:

The added presence of ocular symptoms in AR patients suffering with nasal symptoms deteriorates patients’ quality of life, leads to greater lost productivity and places higher burden on resource utilisation. Studies are therefore needed to test whether treatment options that address ocular in addition to nasal symptoms will improve quality of life and reduce both direct and indirect resource use associated with AR.

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common inflammatory condition of the upper respiratory tract and nasal cavity which often involves the eyes affecting more than 20% of the population in Europe. In a pan-European survey of an unselected populationCitation1, the prevalence of clinically confirmable AR was 22.7% with the lowest prevalence reported for Italy (16.9%) and the highest prevalence in France (24.5%), the UK (26%) and Belgium ((28.5%). An intermediate prevalence rate was reported in Germany (20.6%) and Spain (21.5%).

Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis is characterised by both nasal (Ns) and ocular (Oc) symptoms including rhinorrhoea, sneezing, itchy/blocked nose, sinus pressure, itchy/red eyes, snoring and other sleep problems. Across Europe, over 70% of AR patients report that they suffer from both nasal and ocular symptoms either currently or frequentlyCitation2. In the same study, almost two-thirds (60%) of AR patients indicate that they suffer from itchy eyes and one in three of these (21%) indicate it is the most bothersome symptom of their conditionCitation2. Other studies suggest that 42% of patients suffer from at least one nasal symptom and at least one ocular symptom at moderate/severe levelsCitation3 and that half of all patients (51.7%) consider ocular symptoms to be more annoying than nasal symptomsCitation4. In an analysis of 10,038 AR patients in FranceCitation5, half of those with ocular symptoms considered these to be more annoying than their nasal symptoms, particularly itching (51.9%) and watery eyes (38.6%). Studies have shown that the bothersome nature of AR symptoms can severely affect daily activities, including ability to workCitation6 and examination performanceCitation7,Citation8, as well as affecting quality of life (QoL) and psychosocial well-beingCitation9,Citation10. In addition, there is evidence to suggest that ocular symptoms are under-reportedCitation2. Nearly half of AR patients (46%) reported tiredness due to AR symptoms, 56% of patients reported sleep problems and 37% reported irritabilityCitation2. In another pan-European study, up to 60% of patients frequently reported feeling tired as a result of their AR symptomsCitation11. A survey among primary care practitioners in eight countries indicated that the ocular symptoms are among those most likely to affect ability to perform daily tasksCitation12. Patients report that these symptoms are both troublesomeCitation12 and inadequately controlledCitation2.

Therefore AR imposes a substantial burden with significant economic impact on affected individuals, healthcare systems and societyCitation13 due to its effects on the quality of life of individuals and by its increasing prevalence worldwideCitation14. However, little data has been generated which investigated the increased burden of ocular symptoms (Oc) in addition to nasal symptoms (Ns) on patients with AR.

This manuscript investigates this burden by calculating the effect of removing ocular symptoms on Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), productivity measures and resource utilisation of patients presenting with both nasal and ocular (Ns + Oc) symptoms.

Methods

Study design

The Allergic Rhinitis Disease Specific Programme (DSP), a cross-sectional observational study of consulting patients, run by Adelphi (Macclesfield, UK), was conducted between May and June 2008 and recruited specialists and primary care physicians and their patients in four European markets (France, Germany, Italy and Spain). The DSP is designed as a real world, observational study collecting only information available to the physician/patient at the time of consultation, therefore no tests or investigations are required or conducted for a patient to be included in the study. All patients over the age of 12 years with AR, as diagnosed by their physician, are eligible for inclusion in the survey. Physicians complete a patient record form (PRF) for 4–5 consecutive consulting AR patients, and the same patients are invited to fill out a patient self-completion form (PSC). In order to get a clear picture of the implications of ocular and nasal symptoms in patients with AR, this analysis excluded AR patients with co-morbid asthma and/or COPD.

Physicians record data relating to patient characteristics, diagnosis, symptoms and their severity, common triggers, co-morbidities, current and past drug treatments and healthcare resource utilisation. Patients record information on disease history, symptoms and their severity, the impact of AR on normal activities (including sleep, sport and leisure, work or school) and treatment satisfaction.

As the methodology requires the next 4–5 presenting AR patients for each physician, the DSP sample is representative of the consulting population. All responses are anonymous to preserve patient confidentiality and to avoid bias at the data collection and analysis phases. The study protocol followed ethical procedures including informed consent of all patients for anonymous and aggregated reporting of research findings based on the questionnaires employed. Patients were instructed by the physician to complete the PSC independently and return it in a sealed envelope. Matching the physician and patient responses via patient/physician study numbers allows the PSC data to be linked with comparable data recorded on the physician-completed PRF to highlight any areas of disparity and/or agreement. The analyses conducted for the purposes of this paper investigate data from the matched PRF and PSC records. The full methodology for this survey has been outlined previouslyCitation15,Citation16.

Symptom and HRQoL assessments

The two sub-groups compared on all outcome measures were patients currently suffering from both Ns + Oc symptoms and those who had only nasal symptoms (Ns). This subgroup was defined as those currently suffering from nasal congestion and/or nasal itchiness. The Ns + Oc patient subgroup was defined as those currently suffering from itchy/red eyes and/or watery eyes in addition to having at least one of the nasal symptoms. The current severity of the nasal and ocular symptoms were recorded by the physician as being either not present, mild, moderate or severe.

Health-related quality of life and impact on work, activity and sleep were assessed using the Mini Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (MiniRQLQ)Citation17, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)Citation18 and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment: Allergic Specific Questionnaire (WPAI:AS)Citation19. Within MiniRQLQ, a change in score (of 0.5) is defined as the ‘minimal important difference’ (MID) for each domain as well as the overall score.

Other resource-focused outcome measures in the PSC included: days off work due to AR in the last 3 months, spending on OTC medications for AR over the last 12 months, and the number of AR related visits over the last year to specified healthcare providers.

Three other outcome measures were taken from the physician-completed patient forms: number of drugs currently prescribed for AR, number of visits to the physician (PCP or specialist) related to AR in the last year, and (in appropriate countries) number of visits to a nurse related to AR in the last year.

Statistical methods

Primary analysis for each outcome measure consisted of calculating the average (expected) effect of removing ocular symptoms from patients currently experiencing Ns + Oc symptoms. This can be referred to as the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT).

Secondary analysis attempted to detect whether (statistically significant) increasing scales of ocular severity could be detected on each of the outcome measures (three possible – movements from not present to mild, mild-to-moderate, and moderate-to-severe ocular severity)

Concerning the primary analysis, the nasal only sub-group was utilised to represent the counterfactual observations – what the outcome measures would have been for those patients currently experiencing nasal + ocular symptoms had they not experienced the ocular component.

For this process to work adjustments have to be made for imbalances between the two groups on important confounding variables that might effect the outcome measures. Confounding factors which were controlled for in all analyses included age, gender, BMI, smoking status and non-allergic comorbidities. No control was made for allergic co-morbidities as these may be naturally associated with AR; any outcome differences between the two groups might be a natural consequence of the extra ocular condition.

For similar reasons the investigators were uncertain as to whether to control for the severity of nasal symptoms – in statistical terms it was/is not clear that the severity of nasal symptoms is causally prior to the determination of the presence or absence of ocular symptoms. Hence the primary analysis was conducted twice – once including the severity of the nasal symptoms as a confounding factor and once without.

For the primary analysis the ‘doubly robust’ two-step approach advocated by Ho et al., 2007Citation20 was followed. In the first step, propensity scoring techniques were used to match the patients on the confounding factors in the two groups. A genetic algorithm (allowing matching with replacement) was utilised to perform the matching (statistical package GenMatch in RCitation21). Balance after matching was assessed by examination of empirical quantile–quantile, QQ, plots between the two sub-groups and reduction in bias statistics. The output of the PS technique was a variable which contained the relative number of times each patient was utilised in the matching.

In the second step this variable was utilised as a weight variable in parametric regressions (ordinary least squares and negative binomial regressions – for count data) that modelled the outcome variables and included the confounders as predictors. This methodology is ‘doubly robust’ in the sense that if either the matching or the regression model is correct, then causal estimates will be consistentCitation22. For each Ns + Oc patient, the method subtracts his/her predicted ‘nasal only’ outcome (obtained from the parametric regression) from his/her actual score. The procedure then takes the average of these scores as the ATT estimate. In order to generate unbiased average estimates of a potentially non linear function, Monte Carlo simulations are actually run (10,000) – nasal only predictions varying for each patient dependent upon the particular coefficients draw from the relevant parametric regression multivariate coefficient distribution function. These simulations thus providing 95% confidence intervals along with point estimates of the ATT. Statistical significance at the 0.05 level being ascribed if this confidence interval did not contain zero.

These calculations were conducted utilising the packages MatchitCitation23 and ZeligCitation24 within R. Further details on the approach are provided in Ho et al.Citation20.

For the secondary analysis, it was not possible to use propensity scoring techniques as there were more than two comparison groups. Standard parametric regression analyses (ordinary least squares and negative binomial models) were performed with the inclusion (alongside the confounders from the primary analysis including severity of nasal symptoms) of ordinal binary severity predictors representing the step-up in ocular severity from the previous level. Wald tests were utilised to test the statistical significance of these step-ups. Statistically insignificant ocular severity step-up resulted in the corresponding ocular severities being merged together. The maximum number of statistically significant steps was three for all regions apart from France and Spain where it was two. In these countries, severe patients were combined with moderate ocular patients owing to the small number of severe cases recorded.

All primary statistical analysis were conducted in R Version 2.10.1Citation25. All secondary statistical analysis were conducted in Stata Version 10.1Citation26.

Results

A total of 1640 physician-completed AR patient records (PRFs) were collected, of which 364 had a joint diagnosis of either asthma (346) or COPD (an additional 18) leaving a potential maximum base of 1276. Among these patients, 1009 were currently suffering Ns only or Ns + Oc symptoms. The number of returned patient self-completions (PSCs) varied between countries reducing the total base to 750 for the patient-reported outcome measures. This affects the ability to capture statistically significant differences between the two groups in some countries due to the lack of statistical power.

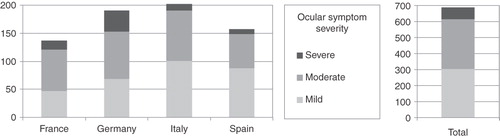

The distribution of patients by nasal severity within symptom group in each country is shown in . The sample of patients who had both Ns + Oc symptoms tended on average to have slightly more severe Ns symptoms, presenting with a higher proportion of severe and a lower proportion of mild patients than their Ns counterparts. One would therefore expect that controlling for nasal severity should lessen the additional impact of ocular symptoms on the outcome measures.

Figure 1. Frequency counts of nasal symptom severities across regions within nasal-only and nasal + ocular symptom comparison groups.

shows the effect of matching patients by the PS algorithm, both before and after matching averages are shown over the confounders, together with the percentage reduction in bias achieved by the matching. This table is pertinent to the number of AR drugs prescribed analysis. Separate PS analyses had to be applied for each outcome measure owing to varying missing responses on each outcome. In this instance significant bias reductions were achieved for all confounders apart from gender (which was already well matched). For other outcome measures bias reductions were often experienced across all confounders. It was noteworthy how well these were matched with the Ns symptom severity indicators.

Table 1. Distribution of confounding variables between comparison groups (before and after propensity score matching for outcomes analysis of number of AR drugs prescribed).

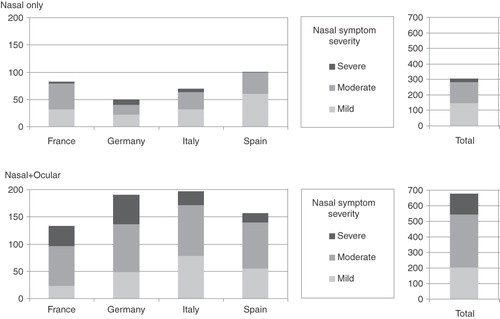

shows the average effect of removing ocular symptoms from patients currently experiencing Ns + Oc symptoms (using the doubly robust method) without taking account of differences in Ns symptom severity (by region and total). For all of the outcome measures listed this effect is statistically significant at the total sample level. All the statistically significant results state that those patients who have both Ns + Oc symptoms would achieve statistically significant improvements (less severe scores) if their Oc symptoms were not present. Having Oc symptoms in addition to Ns symptoms does not result in any improvement in any of the criteria investigated at the total sample level.

Table 2. Outcome results by region – estimated additional burden effect associated with ocular symptoms.

When countries were analysed individually, on all variables where the effect of removing Oc was statistically significant the direction was always the same – it was beneficial to remove the Oc effect. Where differences were not statistically significant, the exact same directionally effect was registered for all remaining outcome variables, with the exception of two (Spain – total visits to healthcare professionals and Germany –WPAI percent work time missed).

Explicitly adjusting for differences in Ns symptom severity between the two groups, as shown in , has had little qualitative impact – for all but two of the outcome variables, removing the Oc component would still lead to a statistically significant improvement at the total base level. The two exceptions being number of drugs prescribed for AR and PSQI global score, which although not significant still indicate the same beneficial directional effect from removing the Oc symptom.

Table 3. Outcome results by region – estimated additional burden effect associated with ocular symptoms.

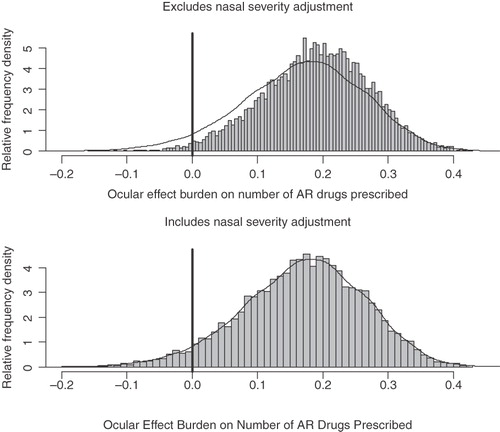

It is instructive to examine the distribution of the 10,000 simulation outcome effects, as displayed in , for the number of AR drugs prescribed both with and without taking into account differences in nasal severity. This presents a much fuller picture of possible effects than merely examining p-values. From this examination it appears that accounting for Ns symptom severity has had little impact on the Oc effect estimate with very similar histograms. It is clear that the great bulk of the simulations are to the right of the zero effect line for both graphs denoting a beneficial effect from the removal of ocular symptoms. It may therefore be a mistake to simply judge the importance of estimates simply on p-values.

Figure 2. Histograms of estimated additional effect burden from ocular symptoms on the number of AR drugs prescribed.

It is not always the case that accounting for differences in Ns symptoms always reduces the magnitude of the statistically significant effect estimate. Whilst it is correct at the total base level that accounting for differences in nasal severity does diminish it within the pure HRQoL instruments (RQLQ and PSQI), its effect over work loss is mixed and consultations with healthcare professionals remains virtually unchanged (rising slightly).

At the individual country level there are fewer statistically significant effect sizes owing to lack of power from the smaller bases. However, in general, the very same trends emerge within each country: all statistically significant effects are in the same direction pointing to removal of ocular symptoms having a beneficial effect; the vast majority of remaining effects, although not statistically significant, also point in this direction; accounting for differences in Ns symptom severity has little impact as shown by the fact that the vast majority of statistically significant effects remain so.

Focusing on the secondary analysis, contrasts the distribution of Oc symptom severities within the regions. At the country level we had to merge severe with moderate for France and Spain owing to the small number of severe Oc symptom patients. shows the number and type of statistically significant ocular severity step-ups achieved by the various regions. All statistically significant step-ups were in the same direction – a worsening in Oc symptom severity being associated with a worse patient outcome.

Table 4. Statistically significant step-ups in ocular symptoms impacting on outcome burdens.

It is clear from that significant increases/step-ups occur at different severity levels. This is most clearly seen in the ‘All’ region column with its higher total base. For example, for total visits to healthcare professionals and work time missed, the outcomes show a significant increase/step-up only from moving to the severe ocular category, whereas for the number of AR drugs prescribed, a significant increase/step-up is observed between patients with no ocular symptoms to those with any ocular symptoms regardless of their severity. Reassuringly, however, the RQLQ Eye domain showed the maximum possible number of step-ups achieved for each region.

Discussion

AR is a common and often clinically underestimated condition affecting a large percentage of the working population. The fact that AR is frequently associated with bothersome ocular symptoms is frequently neglected both clinically and in therapeutic approaches.

This study adds to current knowledge by showing that a large proportion of patients with physician-diagnosed AR also suffer from allergic conjunctivitis. In addition it shows, not unexpectedly, but documented for the first time in such a large cohort, that patients with allergic rhino-conjunctivitis have significantly poorer quality of life, increased healthcare resource consumption and an increased loss in productivity which adds to the overall economic burden of this condition. Taking the simplest and narrowest monetary measure of this burden – loss in wages owing to work absence – a minimum measure of economic effect can be calculated. The average wage in the participant European countries varies from 37 euros a day in Spain to 91 euros a day in GermanyCitation27. With European prevalence of AR estimated at 23%Citation28, the calculated half a day work loss in a 3-month period owing to the additional burden of ocular symptoms, is clearly a significant economic burden to society. These findings hold irrespective of whether allowances are made for differences in the severity of nasal symptoms between Na + Oc and Na only patients. We have also shown, unsurprisingly, that the actual severity of the ocular condition impacts the patient along with its presence and this effect varies between outcome measures.

As the study was undertaken by a wide cross-section of practising physicians, it is of particular relevance for physicians facing or encountering everyday treatment conditions involving AR patients.

This study is in agreement with previous findingsCitation29 showing that the indirect economic burden is greater than the direct costs resulting from the management of the disease. However, compared with the USA, the evidence collected for Europe on this issue is less widespread which reinforces the scientific value of this survey.

This is one of few large studies conducted in European countries which corroborates previous findings in other populations. It underlines the impact of AR not only on quality of life but also as a major contributor to healthcare costs. The study is also one of the first to substantiate the hypothesis that the co-morbidity of allergic conjunctivitis adds to the impairment of QoL caused by AR. It has to be emphasised, however, that in order to appreciate fully the economic impact of the differences between AR and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis a cost of illness study would be required.

Care was taken to correct the data for possible confounding variables. Nevertheless, additional confounders cannot be fully excluded. These might include the effect of different baseline medications and whether each patient group had a higher or lower proportion of patients with perennial AR compared with seasonal AR, the former of which has been associated with more severe symptoms and poorer HRQoLCitation30,Citation31.

No selection of patients was made during the recruitment process and the study was performed in the current AR population within different countries, aiming to capture a holistic sample representing the consulting population. However, it cannot be fully excluded that the likelihood for an individual patient to complete a questionnaire is influenced by differences in patient typology compared with those patients who chose not to complete. Data for the study were collected over a fixed period in a number of countries and regions thereof. Given the geographical dispersion of these countries, it may be reasonable to assume possible differences in the intensity of the AR season based on latitude. Despite the stated limitations, the authors believe the evidence collected represents a valid contribution towards the assessment of the burden of AR. Further interventional studies are needed to demonstrate that therapeutic strategies aimed at improving AR and conjunctivitis in patients with Ns + Oc symptoms will be superior in improving HRQoL compared to treatments aimed at AR only.

Conclusions

This single study, based on a large number of patients in multiple countries, evaluates the effects which removing ocular symptoms might have on patients currently experiencing nasal and ocular complaints. This has been achieved by comparing such patients with those who only experience nasal symptoms using methods that control for important confounding factors. The results indicate, irrespective of controlling for differences in nasal symptom severity, that removing ocular symptoms increases patients HRQoL and lowers the burden of direct and indirect health resource use. Our results also show that the actual severity of the ocular condition, not just its presence, impacts on HRQoL and resource use. Additional ocular symptoms are thus associated with a negative effect on individual daily functioning and burden of illness.

Studies are therefore needed to test whether treatment options that address ocular in addition to nasal symptoms will improve quality of life and reduce both direct and indirect resource use associated with AR.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funding for this study was provided by GlaxoSmithKline. All listed authors have provided input to the manuscript content and meet the criteria for authorship set forth by the International Committee for Medical Journal Editors.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

V.H. and S.K. are employees of Adelphi Real World, Macclesfield, UK. J.C.V. has lectured for and received honoraria from Asche-Chiesi, AstraZeneca, Avontec, Bayer, Bencard, Bionorica, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Essex/Schering-Plough, GSK, Janssen-Cilag, Leti, MEDA, Merck, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Nycomed/Altana, Pfizer, Revotar, Sandoz-Hexal, Stallergens, TEVA, UCB/Schwarz-Pharma, Zydus/Cadila and possibly others, has participated in advisory boards for Asche-Chiesi, Avontec, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Essex/Schering-Plough, GSK, Janssen-Cilag, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Revotar, Sandoz-Hexal, UCB/Schwarz-Pharma and possibly others and has received grants from GSK and MSD. J.M. is or has been member of national or international Scientific Advisory Boards, acted as speaker, or received grants for Research Projects from: Uriach SA, FAES, AstraZeneca, GSK, Hartington Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, UCB Pharma, Schering-Plough, MSD, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. P.D., and W.C. have disclosed that they have to relevant financial relationship.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions and critical review during the development of this manuscript: Mark Small and Peter Anderson from Adelphi Real World, Macclesfield, UK, and Beatrice Gueron, formerly of GlaxoSmithKline.

References

- Bauchau V, Durham SR. Prevalence and rate of diagnosis of allergic rhinitis in Europe. Eur Respir J 2004;24:758-64

- Canonica GW, Bousquet J, Mullol J, et al. A survey of the burden of allergic rhinitis in Europe. Allergy 2007;62:17-25

- Scadding G, Punekar Y. Symptomatic burden of allergic rhinitis (AR) among adults. Presented at Eur Acad Allergol Clin Immunol 2006; Abstract 1660

- Klossek JM, Didier A, Serrano E, et al. Clinical manifestation of acute maxillary sinusitis in general practice: an observational study. Presented at Eur Acad Allergol Clin Immunol 2008; Abstract 1150

- Klossek JM, Annesi-Maesano I, Boucot I, et al. Prevalence, severity and impact of allergic rhinitis in the French community - Survey INSTANT 2006. Presented at Eur Acad Allergol Clin Immunol, 2008; Abstract 1153

- Blanc PD, Trupin L, Eisner M, et al. The work impact of asthma and rhinitis: findings from a population-based survey. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:610-18

- Vuurman EF, van Veggel LM, Sanders RL, et al. Effects of semprex-D and diphenhydramine on learning in young adults with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1996;76:247-52

- Walker S, Khan-Wasti S, Fletcher M, et al. Seasonal allergic rhinitis is associated with a detrimental effect on examination performance in United Kingdom teenagers: case-control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:381-87

- Meltzer EO, Nathan RA, Selner JC, et al. Quality of life and rhinitic symptoms: results of a nationwide survey with the SF-36 and RQLQ questionnaires. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997;99:815-19

- Leynaert B, Neukirch C, Liard R, et al. Quality of life in allergic rhinitis and asthma. A population-based study of young adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:1391-6

- Bousquet J, Williams AE, Kay S, et al. Physician and patient perception differ for symptoms associated with allergic rhinitis (AR) in five European countries. Eur Acad Allergol Clin Immunol, 2007; Abstract 323

- Van Cauwenberge P, Van Hoecke H, Kardos P, et al. The current burden of allergic rhinitis among primary care practitioners and its impact on patient management. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:27-33

- Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA(2)LEN and AllerGen). Allergy 2008;63:8-160

- Nihlen U, Greiff L, Gontnemery P, et al. Incidence and remission of self-reported allergic rhinitis symptoms in adults. Allergy 2006;61:1299-304

- Higgins V, Kay S, Small M. Physician and patient survey of allergic rhinitis: methodology. Allergy 2007;62:6-8

- Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, et al. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: Disease-Specific Programmes – a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:3063-72

- Juniper EF, Guyatt GH. Development and testing of a new measure of health status for clinical trials in rhinoconjunctivitis. Clin Exp Allergy 1991;21:77-83

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193-213

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993;4:353-65

- Daniel Ho, Kosuke Imai, Gary King, et al. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Analysis 2007;15:199-236. http://gking.harvard.edu/files/abs/matchp-abs.shtml

- Diamond A, Sekhon JS. Genetic matching for estimating causal effects: a general multivariate matching method for achieving balance in observational studies. UC Berkeley: Institute of Governmental Studies, 2006. Retrieved from: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/8gx4v5qt

- Robins JM, Rotnitzky A. Comment on the Bickel and Kwon article, ‘Inference for semiparametric models: Some questions and an answer’. Stat Sin 2001;11:920-36

- Ho D, Imai K, King G, et al. Matchit: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J Stat Softw 2007. Available from: http://gking.harvard.edu/matchit/

- Imai K, King G, Lau O. Zelig: Everyone’s Statistical Software, 2006. Available from: http://GKing.Harvard.Edu/zelig

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL http://www.R-project.org, 2009

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2007

- European Working Conditions Observatory. Available from: http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/ewco/studies/tn0911039s/de0911039q.htm

- Bauchan V, Durham SR. Prevalence and rate of diagnosis of allergic rhinitis in Europe. Eur Respir J 2004;24:758-64

- Reed SD, Lee TA, McCrory DC. The economic burden of allergic rhinitis – a critical evaluation of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics 2004;22:345-61

- Stewart MG. Identification and management of undiagnosed and undertreated allergic rhinitis in adults and children. Clin Exp Allergy 2008;38:753-60

- Mullol J, Bachert C, Bousquet J. Management of persistent allergic rhinitis: evidence-based treatment with levocetirizine. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2005;1:265-71