Abstract

Background:

In the last decade, the number of new agents, including monoclonal antibodies, being developed to treat metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) increased rapidly. While improving outcomes, these new treatments also have distinct and known safety profiles with toxicities that may require hospitalizations. However, patterns and costs of hospitalizations of toxicities of these new ‘targeted’ drugs are often unknown.

Objective:

This study aimed to estimate the costs of hospital events associated with adverse events specified in the ‘Special Warnings and Precautions for Use’ section of the European Medicinal Agency Summary of Product Characteristics for bevacizumab, cetuximab, and panitumumab, in patients with mCRC.

Methods:

From the PHARMO Record Linkage System (RLS), patients with a primary or secondary hospital discharge code for CRC and distant metastasis between 2000–2008 were selected and defined as patients with mCRC. The first discharge diagnosis defining metastases served as the index date. Patients were followed from index date until end of data collection, death, or end of study period, whichever occurred first. Hospital events during follow-up were identified through primary hospital discharge codes. Main outcomes for each event were length of stay and costs per hospital admission.

Results:

Among 2964 mCRC patients, 271 hospital events occurred in 210 patients (mean [SD] duration of follow-up: 34 [31] months). The longest mean (SD) length of stay per hospital admission were for stroke (16 [33] days), arterial thromboembolism (ATE) (14 [21] days), wound-healing complications (WHC), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), congestive heart failure (CHF), and neutropenia (all 9 days; SD 5–15). Highest mean (SD) costs per admission were for stroke (€13,500 [€28,800]), ATE (€13,300 [€18,800]), WHC (€10,800 [€20,500]).

Limitations:

Although no causal link could be identified between any specific event and any specific treatment, data from this study are valuable for pharmacoeconomic evaluations of newer treatments in mCRC patients.

Conclusions:

Inpatient costs for events in mCRC patients are considerable and vary greatly.

Introduction

Each year, ∼1 million new cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) are diagnosed worldwide and the highest incidence rates are in North America, Australia/New Zealand, Western Europe, and, in men especially, JapanCitation1. Metastases are already present at CRC diagnosis in a significant proportion of patients, and many patients diagnosed at earlier stages will also eventually develop metastatic diseaseCitation2,Citation3. The development of metastases in patients with CRC tends to occur most often in the liver and lungCitation2.

Recent decades have brought a dramatic increase in the number of new agents being investigated and approved for the treatment of cancer. For metastatic CRC (mCRC), there have been advances in cytotoxic chemotherapies and, more recently, monoclonal antibody treatments. Specifically, agents which target the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (in patients with wild-type KRAS [Kirsten rat sarcoma virus] tumours, as mutated KRAS status in tumours is associated with lack of response to anti-EGFR treatment) have become part of the standard treatment of mCRCCitation4–8. While improving treatment outcomes, these new treatments are also associated with distinct toxicity profiles and some events associated with monoclonal antibodies could be costly. While it is, therefore, important to include the costs of these events in the economic evaluation of different monoclonal antibodies, there has been very limited health economics research to provide such costs.

To our best knowledge, only one study (US claims database analysis) was found that assessed the costs of events of interest in the treatment of mCRCCitation9. Therefore, this longitudinal, population-based study describes the hospital costs of those events documented in the literature and in regulatory agencies approved labels as being associated with monoclonal antibodies (i.e. bevacizumab, cetuximab, and panitumumab) in patients with mCRC in the period 2000–2008 in The Netherlands.

Methods

Data source

Data for this retrospective cohort study were obtained from the PHARMO medical record linkage system (PHARMO RLS), which consists of multiple observational databases linked on a patient level, covering 3.2 million inhabitants of geographic defined areas in The Netherlands. Databases relevant for this study included the Dutch National Medical Register (LMR)Citation10. The LMR is the database comprising all hospital admissions in The Netherlands, i.e., admissions for more than 24 hours and admissions for less than 24 hours for which a bed is required. The hospital records from this database include detailed information concerning the primary and secondary diagnoses, procedures, and dates of hospital admission and discharge. All diagnoses are coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).

Patient population

Patients aged ≥18 years diagnosed with mCRC were identified by hospitalization codes between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2008. All patients with a hospital admission with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis for CRC (ICD-9-CM code 153.x (excluding 153.5), 154.0, 154.1, and 154.8) and metastasis (defined as secondary malignant neoplasms of lymph nodes, respiratory system, digestive system, and other specified sites [ICD-9-CM code 196.0, 196.1, 196.3, 196.5, 197.x (excluding 197.5), 198.x, and 199.0]) were selectedCitation11,Citation12.

To be included in the study, the hospital discharge date for distant metastasis needed to occur no more than 30 days before the hospital discharge date for CRC or anywhere after the hospital admission date for CRC, on condition that the patient was not hospitalized for cancer other than CRC (ICD-9-CM code 140.x-209.6, 230.x-234.x (excluding ICD-9-CM codes used to define CRC and metastasis, including both solid and blood cancers). The index date was defined as the first hospital discharge date of metastasis. Patients with a primary hospital discharge diagnosis for metastasis (same ICD-9-CM codes as used for defining metastasis) within 10 years before the index date were excluded as these metastases might be related to a primary tumor other than CRC. All patients were followed from the index date until the end of data collection in PHARMO RLS (i.e., until death or moving out of PHARMO RLS catchment area), or end of study period (31 December 2008), whichever occurred first.

Outcome measures

For all study patients the following characteristics were determined at index date: gender, age, type of CRC (colon or rectal), site of metastasis, and follow-up period. During follow-up the length of stay and the cost per hospital admission for events of interest were estimated. Events of interest were those that are included in the ‘Special Warnings and Precautions for Use’ section of European Medicinal Agency Summary of Product Characteristics for bevacizumab, cetuximab, and panitumumab, which are currently the only three monoclonal antibodies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of patients with mCRC. Events were identified through primary hospital discharge diagnosis ICD-9-CM codes: acute myocardial infarction (ICD-9-CM code 410), arterial thromboembolism (ICD-9-CM code 444), bleeding (ICD-9-CM code 286–287, 336.1, 430–431, 432.1, 432.9, 459.0, 531–534, 569.3, 569.82–569.83, 578, 626.6, and 626.8–626.9), congestive heart failure (ICD-9-CM code 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, and 428), dermatological conditions (defined as symptoms involving skin and other integumentary tissue (ICD-9-CM code 782)), hypertension (ICD-9-CM code 401–405), neutropenia (ICD-9-CM code 288.0), sepsis (ICD-9-CM code 038.9), stroke (ICD-9-CM code 362.3, 433.1, 434.1, 435–436), venous thromboembolism (ICD-9-CM code 451.1, 451.2, 451.81, 451.9, 453.1, 453.2, 453.8, and 453.9), and wound-healing complications (ICD-9-CM code 87x, 88x, 891–897, 998.3, and 998.8).

The cost per hospital admission was estimated using tariffs as prescribed by the Dutch Healthcare Authority – a national organization that defines all tariffs for admission days, procedures, and medical specialists’ fees in The NetherlandsCitation13. Tariff costs from 2003 were used and indexed to 2008 as later costs (after 2003) on an individual level are not available. Indexing was based on inflation information derived from Statistics Netherlands – a national organization that is responsible for collecting and processing data in order to publish statistics to be used in practice by policymakers and for scientific research. Costs were presented as mean (±standard deviation [SD]) and median (interquartile range [IQR]) cost per event, in units of 1000 Euros (€1000).

Statistical analysis

This is a descriptive study and statistical analyses were performed using SAS procedures organized within SAS Enterprise Guide version 4.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and conducted under UNIX using SAS version 9.2. All results were reported descriptively. Categorical data were presented as counts (n) and proportions (%). Continuous data were presented as means (±SD) and/or medians (IQR).

Results

The study population comprised 2964 patients with mCRC and included similar numbers of males and females (). Patients aged 70–79 represented the largest group by age (32%); mean (±SD) age was 68 (±12) years. A primary diagnosis of colon cancer (69%) was more common than a primary diagnosis of rectal cancer (31%). Overall, the most common metastasis site was the liver (43% in patients with colon cancer and 42% in patients with rectal cancer as primary tumor). Mean (SD) follow-up was 34 (31) months and median (IQR) follow-up was 24 (6–58) months.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients hospitalized for mCRC.

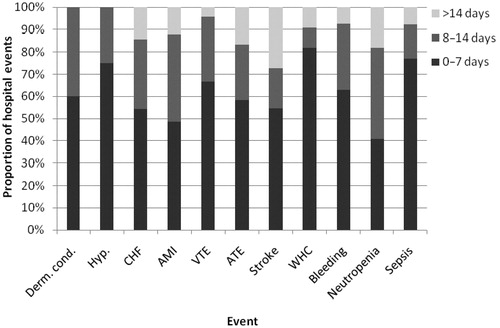

Overall, 271 hospital events were observed among 210 patients. For each type of hospital event, a majority of patients (78% overall) had only one hospitalization. The longest mean (±SD) lengths of stay per primary hospital discharge diagnosis were observed for stroke (16 [±33] days) and arterial thromboembolism (14 [±21] days), followed by wound-healing complications (9 [±15] days), acute myocardial infarction (9 [±9] days), congestive heart failure (9 [±7] days), neutropenia (9 [±5] days, hemorrhage (6 [±6] days), sepsis (6 [±5] days), venous thromboembolism (6 [±5] days), dermatological conditions (6 [±4] days), and hypertension (4 [±3] days). The distribution of length of stay (0–7, 8–13, and 14+ days) for each hospital event is reported in .

The mean (SD) and median (IQR) costs per hospital admission for the events are shown in . The highest mean (SD) costs per hospital admission were observed for stroke (€13,500 [€28,800]), arterial thromboembolism (€13,300 [€18,800]), and wound-healing complications (€10,800 [€20,500]). Lowest mean (SD) costs per hospital admission were observed for dermatological conditions (€5400 [€3500]), venous thromboembolism (€5400 [€5200]), and hypertension (€4100 [€2800]).

Table 2. Cost of hospital events among patients hospitalized for mCRC.

Discussion

Since the emergence of new chemotherapy and monoclonal antibody therapies the treatment outcomes for patients with mCRC have improved. A greater understanding of the cost of the possible toxic effects of these therapies is needed to assist with the economic evaluation of these agents. In this retrospective cohort study the costs of hospital events in patients with mCRC were determined.

During follow-up, per hospital admission, stroke, arterial thromboembolism, and wound-healing complications were the most expensive hospital events, all incurring a mean cost of over €10,000 per hospital admission. In a similar study using US claims data they found similar results for patients with mCRCCitation9. Overall, results in this study showed that hospitalizations due to arterial thromboembolism and wound-healing complications also incurred the highest treatment costs. Also in line with this study was the fact that hypertension and dermatological conditions were relatively less expensive hospital events to treat on a per-admission basis.

In the present study, length of stay was the main driver for costs per hospital event; the hospital events that caused longer lengths of hospital stay were always among those with the highest costs. However, some hospital events that cause longer lengths of hospital stay are not necessarily among the most expensive to treat; therefore, length of stay is not always the only driver of costs. Moreover, it is expected that variance in length of stay vs cost is attributable to ward differences (i.e., shorter stays in intensive care may be more costly than longer stays in a general ward). Unfortunately, as no ward-specific costs are available in PHARMO RLS, this difference could not be examined. It is also likely that practice and resource variations between different institutes, and probably also between regions, exist and would therefore influence cost calculations. However, this information could not be obtained by PHARMO RLS. There were substantial differences between the mean and median hospital costs. This potentially indicates that a minority of patients could have very long stays in hospital, and this was confirmed by evaluation of the distribution in length of stay for each hospital event.

A few limitations to this study need to be considered in interpreting the findings from this study. A major limitation of the study is that potential confounding factors, such as cardiovascular diseases (CVD), were not controlled in the cost estimation. Ideally, if the sample size was large enough for each type of hospital event, a regression model would be used to estimate the ‘expected values’ of hospital costs, controlling for a variety of covariates including CVD. However, due to relatively small sample size, a descriptive approach was used, i.e., average was used to estimate the costs. This cost estimation without controlling for potential confounders is considered to be valid at a mCRC patient population level and thus would not negatively affect the potential use of the study findings in the mCRC patient population. Furthermore, this population-based approach is similar to that was used in the literatureCitation9. Another important limitation was that in this study, reported hospitalization events in patients with mCRC were consistent with the recognized safety profile of monoclonal antibody therapies administered to patients with mCRC. However, no causal link between any specific event and any specific monoclonal antibody therapy was investigated or identified, because the objective of this study was to estimate the hospital costs of events of interest to provide valuable information for economic evaluation of monoclonal antibody treatments at a mCRC patient population level. The assumption was that the hospital costs of an event would be the same no matter which anti-cancer drug caused that event. The third limitation to this study was that patients only could be included in the study if they were hospitalized for CRC and for metastasis. In the Dutch Medical RegisterCitation10, only admissions for which a bed is required are captured. Consequently, some (m)CRC diagnoses were missed. However, it is expected that the hospital events of these patients do not differ from those included in our study cohort. The fourth limitation to this study was that indirect costs of hospital events were not included in the assessment, although these are likely to be substantial contributors to the total costs incurred by healthcare systems and society in general. Finally, the findings from this study are specific to patients in The Netherlands and its healthcare system, and may not therefore be wholly transferable as a guide to costs in other countries. In conclusion, this study estimated direct hospitalization costs for hospital events among patients with mCRC. The main finding from this study highlights that inpatient costs for those hospital events are considerable and vary greatly. Although no causal link could be identified between any specific event and any specific treatment, data from this study is valuable to the pharmacoeconomic evaluations of newer treatments in patients with mCRC.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was financially supported by Amgen Inc. No limitations were set with regard to the conduct of the study and the writing of the manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

J. A. Overbeek, M. P. P. van Herk-Sukel, and R. M. C. Herings are employees of the PHARMO Institute for Drug Outcomes Research which received funding from Amgen Inc. in connection with conduct of this study. Z. Zhao, B. L. Barber, and S. Gao are employees of Amgen Inc.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance was provided by ApotheCom ScopeMedical Ltd, funded by Amgen Inc.

References

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:74–108

- Ramsey SD, Berry K, Etzioni R. Lifetime cancer-attributable cost of care for long term survivors of colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:440–5

- van Herk-Sukel MP, van de Poll-Franse LV, Lemmens VE, et al. New opportunities for drug outcomes research in cancer patients: the linkage of the Eindhoven Cancer Registry and the PHARMO Record Linkage System. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:395–404

- Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J, et al. Randomized, phase III trial of panitumumab with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) versus FOLFOX4 alone as first-line treatment in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: the PRIME study. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4697–705

- Peeters M, Price TJ, Cervantes A, et al. Randomized phase III study of panitumumab with fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) compared with FOLFIRI alone as second-line treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4706–13

- Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, et al. Biomarkers predicting clinical outcome of epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:1308–24

- van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1408–17

- Scheer MG, Sloots CE, van der Wilt GJ, et al. Management of patients with asymptomatic colorectal cancer and synchronous irresectable metastases. Ann Oncol 2008;19:1829–35

- Fu AZ, Zhao Z, Wang S, et al. Hospital costs of adverse events in patients receiving treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. Value Health 2011;14:A173

- Dutch Hospital Data. Available online at: http://www.dutchhospitaldata.nl. Accessed 18 August 2011

- Song X, Zhao Z, Barber B, et al. Cost of illness in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Med Econ 2011;14:1–9

- Song X, Zhao Z, Barber B, et al. Treatment patterns and metastasectomy among mCRC patients receiving chemotherapy and biologics. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:123–30

- The Dutch Healthcare Authority. Available online at: http://www.nza.nl. Accessed 18 August 2011