Abstract

Background:

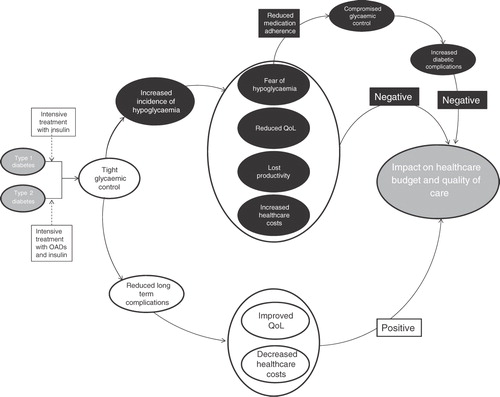

The clinical goal in the treatment of diabetes is to achieve good glycemic control. Tight glycemic control achieved with intensive glucose lowering treatment reduces the risk of long-term micro- and macro-vascular complications of diabetes, resulting in an improvement in quality-of-life for the patient and decreased healthcare costs. The positive impact of good glycemic control is, however, counterbalanced by the negative impact of an increased incidence of hypoglycemia.

Methods:

A search of PubMed was conducted to identify published literature on the impact of hypoglycemia, both on patient quality-of-life and associated costs to the healthcare system and society.

Results:

In people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, hypoglycemia is associated with a reduction in quality-of-life, increased fear and anxiety, reduced productivity, and increased healthcare costs. Fear of hypoglycemia may promote compensatory behaviors in order to avoid hypoglycemia, such as decreased insulin doses, resulting in poor glycemic control and an increased risk of serious health consequences. Every non-severe event may be associated with a utility loss in the range of 0.0033–0.0052 over 1 year, further contributing to the negative impact.

Limitations:

This review is intended to provide an overview of hypoglycemia in diabetes and its impact on patients and society, and consequently it is not a comprehensive evaluation of all studies reporting hypoglycemic episodes.

Conclusion:

To provide the best possible care for patients and a cost-effective treatment strategy for healthcare decision-makers, a treatment that provides good glycemic control with a limited risk of hypoglycemia would be a welcome addition to diabetes management options.

Introduction

Diabetes is a major cause of morbidity and premature mortality. Long-term complications of the disease, which are a consequence of prolonged hyperglycemia, include retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and cardiovascular disease. These complications have a considerable impact on health, a negative impact on patient quality-of-lifeCitation1,Citation2, and represent a significant proportion of the economic burden of diabetes. The clinical goal in the treatment of diabetes is to achieve good glycemic control. Tight glycemic control with intensive diabetes therapy prevents or delays microvascular complications, and reduces cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, thus improving health-related quality-of-life. Intensive diabetes therapy to achieve optimal glycemic control is also a cost-effective treatment in that the increased treatment costs are offset by the reduced cost of treating diabetes-related complications and the improvement in quality-of-lifeCitation3,Citation4.

However, a frequent complication of intensive diabetes therapy is hypoglycemia. The Diabetes Complications and Controls Trial (DCCT) found that intensive therapy in subjects with type 1 diabetes caused a 3-fold increase in the number of hypoglycemic events, compared with those treated less aggressivelyCitation5. Similarly, the maintenance of tight glycemic control in individuals with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes led to a significant increase in the incidence of hypoglycemia in the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)Citation6. Hypoglycemia is consequently a major limiting factor in the management of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, indeed were it not for the problem of hypoglycemia, glycemia targets would be much easier to achieve.

Here we review the effects of hypoglycemia on patient well-being and the associated costs to the healthcare system and society; and how together these impact on the overall management of patients with diabetes, see .

Methods

A search of PubMed was conducted to identify published literature on hypoglycemia in diabetes. The search was originally conducted on 15 October 2009, with no restrictions placed on search date (i.e., search dates were 1966 to 15th October 2009 inclusive), and subsequently updated in March 2011. Search terms included: diabetes; fear and hypoglyc*; (QoL or quality-of-life) and hypoglyc*; hypoglyc* and utilit*; hypoglyc* and cost; hypoglyc* and a search string including euroqol, SF36, EQ-5D, and QALY. Identified publications were screened and relevant studies selected for inclusion in this review. There were no pre-defined inclusion or exclusion criteria, studies were deemed relevant if the reported outcomes were specific to the effects of hypoglycemia (focus on fear of hypoglycemia, HRQoL, and costs), rather than diabetes in general.

Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia (low blood glucose) can occur suddenly and with varying severity. Common causes of hypoglycemia include; over-medication with insulin, delays in mealtimes or insufficient carbohydrate intake to match insulin dose, unplanned physical activity, or insufficient carbohydrate intake during physical activity. Symptoms of hypoglycemia include, but are not limited to, pounding heart, trembling, hunger, and sweating. Symptoms often include difficulty concentrating and/or frank confusionCitation7, but can, in severe cases, include seizure, coma, and even deathCitation8. Hypoglycemic episodes can be categorized as either severe, events that require the assistance of another person to actively administer a remedy, or non-severe, events which do not require assistance from another person. These non-severe hypoglycemic events may be symptomatic events documented as typical symptoms of hypoglycemia and confirmed by a measured low blood glucose level. They may also be asymptomatic and not accompanied by typical symptoms, but confirmed by a low blood glucose reading, or, more commonly, having typical symptoms, but not confirmed by a blood glucose readingCitation9.

It has been estimated that patients with insulin-treated type 1 and type 2 diabetes experience an average of 43 and 16 non-severe symptomatic hypoglycemic episodes per year, respectivelyCitation10. For severe hypoglycemia, up to two episodes are experienced annually by patients with type 1 diabetes and approximately one episode in 5 years by patients with type 2 diabetes. Severe hypoglycemia is more common in those with a history of hypoglycemia and with increasing duration of insulin treatmentCitation10,Citation11. However, it is difficult to accurately determine the frequency of hypoglycemic episodes due to the lack of consistency in definition and differences in data collection. Patient recall is frequently used, and can be inaccurateCitation12. Also, patient databases can under-estimate the number of episodes, particularly non-severe episodes, as patients infrequently report them to their physicianCitation13.

Nocturnal hypoglycemia which occurs during sleep is common, affecting up to 50% of adults and 78% of children, but is often asymptomatic and undetectedCitation14. Undetected nocturnal hypoglycemia may contribute to hypoglycemic unawareness, anxiety, and loss of vitalityCitation14,Citation15. Severe nocturnal hypoglycemia is suspected to contribute to the ‘dead-in-bed syndrome’ which is responsible for an estimated 6% of all deaths in patients with diabetes below 40 years of ageCitation16.

Summary

Symptoms of hypoglycemia include, but are not limited to, pounding heart, trembling, hunger, and sweating. Symptoms also often include difficulty concentrating and/or confusion.

Hypoglycemic episodes can be categorized as either severe, events that require the assistance of another person, or non-severe, events which do not require assistance from another person.

Nocturnal hypoglycemia which occurs during sleep is common, but is often asymptomatic and undetected.

Fear of hypoglycemia

The negative consequences and unpleasant symptoms associated with hypoglycemia may lead to significant anxiety or fear of hypoglycemia in patients with diabetesCitation17. There may also be other psychological manifestations associated with the constant threat of hypoglycemia, such as chronic anxiety which can affect normal sleep and normal domestic and social life. Nocturnal hypoglycemia is particularly feared, as in this state the usual warning symptoms are not felt.

The Hypoglycemic Fear Survey (HFS) was developed to measure the degree of diabetes-related fear experienced by patients and their relativesCitation18. The HFS is divided into sections on worry and behavior; the behavior sub-scale includes items relating to diabetes self-management, and the worry sub-scale is concerned with items relating to anxiety provoking aspects of hypoglycemiaCitation17.

Unsurprisingly, the development of fear of hypoglycemia is associated with a history of hypoglycemia. In a study of patients with type 1 diabetes, Irvine et al.Citation19 found that high scores on the HFS behavior scale were significantly associated with an increased frequency of past hypoglycemia episodes. They also reported that higher levels of fear, according to the HFS worry scale, were reported by patients with a lower mean daily blood glucose level and higher mean blood glucose level variability, i.e., those patients at a higher risk of hypoglycemia. HFS worry scores were also found to be positively associated with a history of hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes by Polonsky et al.Citation20. In another study, patients with type 1 diabetes reported an increased fear of hypoglycemia with increased frequency of severe hypoglycemic episodes, and patients with type 2 diabetes reported increased fear as both the number of mild/moderate and severe episodes increasedCitation21. These studies suggest that fear of hypoglycemia is linked with both the severity and frequency of previous hypoglycemic episodes.

Fear of hypoglycemia has also been connected to state and trait anxiety. Polonsky et al.Citation20 observed that in patients with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes there was a correlation between higher scores on the worry scale of the HFS and higher levels of trait anxiety and general fearfulness. In patients with type 1 diabetes, higher scores on the worry scale were also associated with difficulty in discriminating between anxiety and initial hypoglycemia symptomsCitation20. A diminished ability to discriminate between anxiety and hypoglycemia could delay or prevent the patient from responding appropriately to hypoglycemia, and thus a more severe hypoglycemic episode may occur.

In addition to psychological distress, fear of hypoglycemia can have a behavioral impact on diabetes management and metabolic control. In order to avoid hypoglycemia, patients may reduce or omit an insulin dose, which may result in sub-optimal glucose control and increase the risk of long-term complicationsCitation17. For some patients immediate consequences, such as hypoglycemia, are more tangible than the possibility of future health problems. The impact of hypoglycemia and fear of future hypoglycemic episodes was assessed via a self-administered survey in 202 patients with type 1 and 133 patients with type 2 diabetesCitation13. Following a mild or moderate hypoglycemic episode, 37.8% of type 1 and 29.9% of type 2 diabetes patients reported increased fear of future episodes; and 74.1% and 43.3%, respectively, reported modifying their insulin dose. Following a severe hypoglycemic episode the majority of patients; 63.6% type 1 and 84.2% type 2, reported increased fear of future episodes; and 78.2% and 57.9%, respectively, reported modifying their insulin doseCitation13. A recent survey of 1404 employed individuals with diabetes across the US, UK, Germany, and France found that, of the 1024 individuals taking insulin, 25% decreased their insulin dose following a non-severe hypoglycemic episodeCitation22.

Fear of hypoglycemia is also common among the parents of children with diabetesCitation23. Scores on the behavior scale of the HFS, particularly of mothers, suggest that they may maintain slightly higher than optimal glucose levels in their children in order to avoid hypoglycemiaCitation24,Citation25.

Fear of hypoglycemia is a major contributor to health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) in patients with diabetes. Patients with hypoglycemia symptoms report more fear and worry of hypoglycemia and are more affected by their diabetes compared with those without hypoglycemia symptomsCitation26.

Summary

Fear of hypoglycemia is widespread and impacts patient lifestyle.

Fear of hypoglycemia is associated with the frequency and severity of previous hypoglycemic episodes.

Glycemic control can be compromised as fear of future hypoglycemic episodes may result in patients modifying their insulin dose.

Quality-of-life (utility)

Hypoglycemia has a major impact on patient lives in terms of physical, mental, and social functioning; all aspects of life can be affected including employment, driving, travel, and leisure activitiesCitation27. Hypoglycemia can have both short- and long-term effects on HRQoLCitation28. Short-term effects relate to the symptoms associated with the actual episode and risks of dangerous situations. Long-term effects relate to the negative psychological sequelae, including behavioral changes and fear of future episodes. Patients suffering hypoglycemic episodes are more likely to develop anxiety and panic attacksCitation17,Citation29. Across the studies summarized in

Table 1. Studies reporting utility of hypoglycemia.

In a study of 309 Swedish patients with type 2 diabetes, 37% (n = 115) reported hypoglycemic symptoms in the past month (very few patients reported severe events, n = 7). Health-related utility, as measured via the EQ-5D, was significantly lower in patients with hypoglycemia symptoms (0.70) than those without (0.77), (p = 0.006)Citation26. In another study of subjects with type 2 diabetes (n = 1984), 62.9% reported symptoms of hypoglycemia in the past 6 monthsCitation30. Compared with subjects suffering no hypoglycemic episodes, subjects with hypoglycemic episodes of any severity reported lower HRQoL, as measured by EQ-5D (0.78 vs 0.86; p < 0.0001) and greater fear and worry of hypoglycemia, as measured by the HFS (17.5 vs 6.2; p < 0.001). There was a negative association between symptom severity and HRQoL (p < 0.0001), and a positive association between symptom severity and fear of hypoglycemia (p < 0.0001)Citation30.

The effect of fear of hypoglycemia was explored in a standard gamble study. In this study, participants were asked to rate a basic type 2 diabetes health state describing a patient with good glycemic control. They were then asked to rate the same health state, but with an additional attribute such as fear of hypoglycemia, in this way the disutility of the attribute could be determined. Fear of hypoglycemia was associated with a significant disutility (p < 0.001). Rarely worrying about hypoglycemia was associated with a utility change of −0.01 and sometimes worrying was associated with a utility change of −0.03Citation31, suggesting that increasing fear is associated with decreasing utility.

Other studies have demonstrated that HRQoL decreases with increasing severity and also with increasing frequency of hypoglycemic episodes. A survey of 861 patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes found that mean health-related utility decreased as the severity of hypoglycemia increased; the mean EQ-5D score as a function of one or more episodes in the past 3 months was 0.53 for severe, 0.65 for mild/moderate, and 0.77 for nocturnal hypoglycemiaCitation32. Likewise, a large survey in patients with type 2 diabetes conducted across seven European countries reported scores of 0.54 for severe, 0.66 for moderate, and 0.71 for mild hypoglycemia, compared with 0.73 for no hypoglycemiaCitation33. A survey which combined severity and frequency into an index score demonstrated a significant impact of the index score on EQ-5D scoresCitation34.

A loss of utility with increasing frequency of non-severe hypoglycemic episodes was observed in a time-trade-off study conducted in Canada and the UK. The estimated utility loss was –0.0033 per event for 1 yearCitation28. A UK-based study examined the effect of both frequency and severity of hypoglycemia on health-related utility (EQ-5D) in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetesCitation35. Data were derived from two previous postal surveys. The study demonstrated that the most predictive estimate of health-related utility was fear of hypoglycemia. Each symptomatic hypoglycemic episode corresponded to a −0.0142 decrement in utility over a 3-month period (corresponding to a utility reduction of −0.0036 per event for 1 year), and each severe event had a utility reduction of −0.047 (corresponding to −0.0118 per severe event for 1 year)Citation35. In an appraisal by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) of long-acting insulin a utility reduction of −0.0052 per non-severe event was usedCitation36.

Hypoglycemia and quality-of-life

Hypoglycemia has a large impact on patient lives in terms of physical, mental, and social functioning; all aspects of life can be affected including employment, driving, travel, and leisure activities.

Quality-of-life decreases with increasing frequency and severity of hypoglycemic events.

Studies suggest that each non-severe hypoglycemic event reduces utility in the range of −0.0033 to −0.0052.

Impact on costs

Hypoglycemia is not only associated with considerable cost to the individual in terms of their wellbeing, it also represents a substantial cost burden to healthcare systems and society. Costs are incurred when healthcare resources are used to treat a hypoglycemic event (direct costs) and also when absence from work results in lost productivity (indirect costs).

The cost of an episode of hypoglycemia is dependent on the severity of the episode, and ranges from minimal for a mild episode, to very high for a severe episode requiring hospitalization. However, even for episodes defined as the same severity there is wide variation in published cost per episode (

Table 2. Studies reporting costs of hypoglycemia.

There are more studies that have evaluated the cost of severe hypoglycemia, most likely as the costs associated with such episodes are more defined; hospitalization, emergency services, healthcare professionals, diagnostic tests, treatments administered, etc. Also, because the cost of a severe hypoglycemic episode is higher than that of a mild episode, one may assume it has a bigger impact on the economy. However, the annual costs of non-severe episodes of hypoglycemia should not be overlooked. Due to the greater event frequency non-severe hypoglycemia may incur similar annual costs to severe hypoglycemia. Annual out-of-pocket costs per person attributable to the treatment of hypoglycemia were similar for mild/moderate events and severe events in the study by Harris et al.Citation38. An important cost component related to hypoglycemic events is the increased frequency of blood glucose testing after an event (extra lancets, test strips, alcohol swaps). Studies have demonstrated that, following a hypoglycemic episode, patients monitor their blood glucose more frequently and, consequently, the use of blood glucose tests is increasedCitation22,Citation39,Citation40. Leiter et al.Citation13 reported an average of two extra tests within 24 hours of a mild event and three extra tests 24 hours after a severe event. Brod et al.Citation22 reported an average of 5.9 extra tests in the week following a non-severe event.

The contribution of lost productivity to the cost of hypoglycemia is considerable. Lost productivity following a severe hypoglycemic episode is not surprising considering the effects of such events. In the study by Reviriego et al.Citation41, , lost productivity was estimated to account for ∼35% of the cost of a severe hypoglycemic episode. Leiter et al.Citation13 demonstrated that after a severe event 25–32% individuals went home from work/school and 20–26% stayed home the following day.

However, the impact of non-severe hypoglycemic episodes on productivity is not inconsequential. In the study by Leiter et al.Citation13, following a mild event, 7–10% of individuals went home from work/school and 2–9% stayed home the next day. Similarly, in the survey by Brod et al.Citation22, of 1404 employed individuals with diabetes across the US, UK, Germany, and France, a substantial proportion of respondents across all countries reported missing work as a result of a non-severe hypoglycemic episode. Of respondents who reported having a non-severe hypoglycemic episode at work, 18.3% reported missing work. Episodes experienced outside working hours also had an impact on lost productivity (14.3% reporting missed work) and 22.7% of respondents experiencing a nocturnal non-severe hypoglycemic episode were either late for work or missed a whole day. The estimated lost productivity cost per non-severe hypoglycemic episode ranged from $15–$93 across the four countries, costs were highest for nocturnal episodesCitation22.

Despite the variability in published figures, it is evident that hypoglycemia represents a substantial cost burden to healthcare systems and society. It should also be noted that the cost of hypoglycemia is likely to be considerably more if the negative impact on glycemic control is added into the equation (), in that, as patients maintain higher than optimal glucose levels in order to avoid hypoglycemia, the risk of costly long-term complications is increased. There is clearly a paucity of data in this area and more economic studies are needed to accurately define the direct and indirect costs associated with both hypoglycemia and any consequent effects on glycemic control.

Costs of hypoglycemia

Severe hypoglycemia represents a substantial cost burden to healthcare systems

The average published cost of treating a hypoglycemic episode is variable

Due to event frequency the cost of mild/moderate hypoglycemic events is significant with both extra direct costs (for extra lancets and test strips) and indirect costs (absence from work) and

A paucity of cost data for hypoglycemia identifies an area of future research.

Discussion

This review highlights the considerable negative effects of hypoglycemia on patient quality-of-life and the substantial costs to the healthcare system and society, and how together these factors can impact the overall management of people with diabetes. To provide the best possible care for patients, decision-making based on both clinical and economic evidence is essential. In today’s economic climate, interventions must be shown to be good value for money, with Health Technology Assessment bodies such as the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK, the Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency (TLV) in Sweden, and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) in Australia, utilizing cost-effectiveness thresholds to determine which treatments should be funded through national healthcare systems. The determination of cost-effectiveness takes into consideration the costs and HRQoL associated with a treatment over currently used therapies.

This review focused on studies that reported outcomes specifically related to the effects of hypoglycemia, and it is acknowledged that it may not be fully comprehensive due to the focus on fear of hypoglycemia, HRQoL, and costs. Other clinical outcomes such as increased risk of dementiaCitation42 or increased risk of cardiovascular eventsCitation43 were not in scope for this review. Nevertheless, it gives a clear overview of the impact that hypoglycemia has on the patient, the healthcare system, and society. Studies evaluating interventions to avoid or reduce the incidence of hypoglycemic episodes were not included, as this was not an objective of the review. However, it is evident that such interventions should be a key factor in diabetes management. Studies have demonstrated that improved education on hypoglycemia symptom awareness can reduce the incidence of severe hypoglycemiaCitation44,Citation45. Similarly, a study that assigned a ‘care ambassador’ to youths with diabetes to monitor and encourage routine diabetes care visits demonstrated a reduced rate of hypoglycemia in these individualsCitation46. By reducing the rate of hypoglycemia, cost savings have been observed with these education-based programsCitation45,Citation46. Basal human insulin preparations, such as NPH insulin, have a pharmacodynamic profile that falls short of that of endogenous insulin; they have a sub-optimal duration of action, a marked peak effect and high within-patient variability, which can predispose patients to hypoglycemia. However, the newer basal insulin analogs, such as glargine and detemir, have no significant peak activity, longer duration of action, less variability, and are consequently less prone to triggering hypoglycemia. These newer agents consequently fulfil some of the unmet needs for patients with diabetes. Furthermore, they have been shown to be cost-effective compared with NPH insulin, largely due to the cost savings associated with reduced hypoglycemic eventsCitation47,Citation48.

Conclusions

For diabetes treatment the ultimate goal is good glycemic control, achieved without debilitating hypoglycemic episodes which compromise patient quality-of-life and adherence to their medication – and ultimately increase healthcare costs. Interventions that reduce the frequency and severity of hypoglycemia, whilst maintaining glycemic control are likely to improve patient quality-of-life and reduce healthcare costs, i.e., represent a cost-effective treatment strategy for healthcare decision-makers.

Declaration of interest

TC is an employee of Novo Nordisk who sponsored this project. CF and SG are employees of Abacus International a private health economic consultancy company who were paid by Novo Nordisk to conduct the review. All authors contributed to the design of the review and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This review was funded by Novo Nordisk A/S.

References

- U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients is affected by complications but not by intensive policies to improve blood glucose or blood pressure control (UKPDS 37). Diabetes Care 1999;22:1125–36

- Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Quality of life and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 1999;15:205–18

- Gray A, Raikou M, McGuire A, et al. Cost effectiveness of an intensive blood glucose control policy in patients with type 2 diabetes: economic analysis alongside randomised controlled trial (UKPDS 41). United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Group. BMJ 2000;320:1373–8

- Klonoff DC, Schwartz DM. An economic analysis of interventions for diabetes. Diabetes Care 2000;23:390–404

- Hypoglycemia in the diabetes control and complications trial. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Diabetes 1997;46:271–86

- Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet 1998;352:837–53

- Hepburn DA. Symptoms of hypoglycemia. In: Frier BM, ed. Hypoglycemia and diabetes: clinical and physiological aspects. London: Edward Arnold, 1993:93-103

- Cryer PE. Hypoglycemia: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997

- Defining and reporting hypoglycemia in diabetes: a report from the American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1245–9

- Donnelly LA, Morris AD, Frier BM, et al. Frequency and predictors of hypoglycaemia in Type 1 and insulin-treated Type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. Diabet Med 2005;22:749–55

- Cryer PE, Davis SN, Shamoon H. Hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1902–12

- Heller S, Chapman J, McCloud J, et al. Unreliability of reports of hypoglycaemia by diabetic patients. BMJ 1995;310:440

- Leiter LA, Yale JF, Chiasson JL, et al. Assessment of the impact of fear of hypoglycemic episodes on glycemic and hypoglycemia management. Can J Diabetes 2005;29:186–92

- Allen KV, Frier BM. Nocturnal hypoglycemia: clinical manifestations and therapeutic strategies toward prevention. Endocr Pract 2003;9:530–43

- Veneman T, Mitrakou A, Mokan M, et al. Induction of hypoglycemia unawareness by asymptomatic nocturnal hypoglycemia. Diabetes 1993;42:1233–7

- Sovik O, Thordarson H. Dead-in-bed syndrome in young diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 1999;22(2 Suppl):40–2

- Wild D, von Maltzahn R, Brohan E, et al. A critical review of the literature on fear of hypoglycemia in diabetes: implications for diabetes management and patient education. Patient Educ Couns 2007;68:10–5

- Cox DJ, Irvine A, Gonder-Frederick L, et al. Fear of hypoglycemia: quantification, validation, and utilization. Diabetes Care 1987;10:617–21

- Irvine AA, Cox D, Gonder-Frederick L. Fear of hypoglycemia: relationship to physical and psychological symptoms in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Health Psychol 1992;11:135–8

- Polonsky WH, Davis CL, Jacobson AM, et al. Correlates of hypoglycemic fear in type I and type II diabetes mellitus. Health Psychol 1992;11:199–202

- Sauriol L, Yale JF, Ciasson JL, et al. Fear of hypoglycaemia in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: the AID hypo on QoL study. 2006. Available at: http://www.katalyst.on.ca/documents/CDA1Poster.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2010

- Brod M, Christensen T, Thomsen TL, et al. The impact of non-severe hypoglycemic events on diabetes management and work productivity. Value in Health 2011; (in press)

- Barnard K, Thomas S, Royle P, et al. Fear of hypoglycaemia in parents of young children with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr 2010;10:50

- Haugstvedt A, Wentzel-Larsen T, Graue M, et al. Fear of hypoglycaemia in mothers and fathers of children with Type 1 diabetes is associated with poor glycaemic control and parental emotional distress: a population-based study. Diabet Med 2010;27:72–8

- Patton SR, Dolan LM, Henry R, et al. Fear of hypoglycemia in parents of young children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2008;15:252–9

- Lundkvist J, Berne C, Bolinder B, et al. The economic and quality of life impact of hypoglycemia. Eur J Health Econ 2005;6:197–202

- Frier BM. How hypoglycaemia can affect the life of a person with diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2008;24:87–92

- Levy AR, Christensen TL, Johnson JA. Utility values for symptomatic non-severe hypoglycaemia elicited from persons with and without diabetes in Canada and the United Kingdom. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:73

- Costea M, Ionescu-Tirgoviste C, Cheta D, et al. Fear of hypoglycemia in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic patients. Rom J Intern Med 1993;31:291–5

- Marrett E, Stargardt T, Mavros P, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in a survey of patients treated with oral antihyperglycaemic medications: associations with hypoglycaemia and weight gain. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009;11:1138–44

- Matza LS, Boye KS, Yurgin N, et al. Utilities and disutilities for type 2 diabetes treatment-related attributes. Qual Life Res 2007;16:1251–65

- Davis RE, Morrissey M, Peters JR, et al. Impact of hypoglycaemia on quality of life and productivity in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:1477–83

- Alvarez-Guisasola F, Yin DD, Nocea G, et al. Association of hypoglycemic symptoms with patients' rating of their health-related quality of life state: a cross sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:86

- Solli O, Stavem K, Kristiansen IS. Health-related quality of life in diabetes: the associations of complications with EQ-5D scores. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:18

- Currie CJ, Morgan CL, Poole CD, et al. Multivariate models of health-related utility and the fear of hypoglycaemia in people with diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1523–34

- Warren E, Weatherley-Jones E, Chilcott J, et al. Systematic review and economic evaluation of a long-acting insulin analogue, insulin glargine. Health Technol Assess 2004;8:iii,1–57

- Jonsson L, Bolinder B, Lundkvist J. Cost of hypoglycemia in patients with Type 2 diabetes in Sweden. Value Health 2006;9:193–8

- Harris SB, Leiter LA, Yale JF, et al. Out-of-pocket costs of managing hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes and insulin-treated type 2 diabetes. Can J Diabetes 2007;31:25–33

- Farmer A, Balman E, Gadsby R, et al. Frequency of self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes: association with hypoglycaemic events. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:3097-3104

- Hansen MV, Pedersen-Bjergaard U, Heller SR, et al. Frequency and motives of blood glucose self-monitoring in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009;85:183–8

- Reviriego J, Gomis R, Maranes JP, et al. Cost of severe hypoglycaemia in patients with type 1 diabetes in Spain and the cost-effectiveness of insulin lispro compared with regular human insulin in preventing severe hypoglycaemia. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:1026-32

- Whitmer RA, Karter AJ, Yaffe K,et al. Hypoglycemic episodes and risk of dementia in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2009;301:1565–72

- Johnston SS, Conner C, Aagren M, et al. Evidence linking hypoglycemic events to an increased risk of acute cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1164–70

- Hermanns N, Kulzer B, Krichbaum M, et al. Long-term effect of an education program (HyPOS) on the incidence of severe hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010;33:e36

- Nordfeldt S, Johansson C, Carlsson E, et al. Prevention of severe hypoglycaemia in type I diabetes: a randomised controlled population study. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:240–5

- Svoren BM, Butler D, Levine BS, et al. Reducing acute adverse outcomes in youths with type 1 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2003;112:914–22

- Bullano MF, Al-Zakwani IS, Fisher MD, et al. Differences in hypoglycemia event rates and associated cost-consequence in patients initiated on long-acting and intermediate-acting insulin products. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:291–8

- Gschwend MH, Aagren M, Valentine WJ. Cost-effectiveness of insulin detemir compared with neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes using a basal-bolus regimen in five European countries. J Med Econ 2009;12:114–23

- Vexiau P, Mavros P, Krishnarajah G, et al. Hypoglycaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with a combination of metformin and sulphonylurea therapy in France. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008;10(Suppl 1):16–24

- Heaton A, Martin S, Brelje T. The economic effect of hypoglycemia in a health plan. Manag Care Interface 2003;16:23–7

- Leese GP, Wang J, Broomhall J, et al. Frequency of severe hypoglycemia requiring emergency treatment in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a population-based study of health service resource use. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1176–80

- Curkendall SM, Natoli JL, Alexander CM, et al. Economic and clinical impact of inpatient diabetic hypoglycemia. Endocr Pract 2009;15:302–12

- Hammer M, Lammert M, Mejias SM, et al. Costs of managing severe hypoglycaemia in three European countries. J Med Econ 2009;12:281–90

- Rhoads GG, Orsini LS, Crown W, et al. Contribution of hypoglycemia to medical care expenditures and short-term disability in employees with diabetes. J Occup Environ Med 2005;47:447–52