Abstract

Objective:

To examine how changes in the medication possession ratio (MPR) affect the probability of multiple sclerosis (MS) relapses and total and MS-related charges among patients treated with glatiramer acetate (GA).

Methods:

Data were obtained from i3 InVisionTM Data Mart for January 1, 2006 through March 31, 2010. Patients were included if they were diagnosed with MS, initiated therapy with GA, and had continuous insurance coverage from 6 months prior through 24 months after initial use of GA (n = 839). Multivariate regressions which controlled for patient characteristics examined the association between achievement of alternative MPR goals and patient relapses and charges.

Results:

Patients who achieved an MPR of at least 0.7 had significantly lower odds of relapse than those with MPR thresholds below 0.7, with achievement of a threshold of 0.7, 0.8, or 0.9, associated with an odds ratio of relapse of 0.545 (95% CI = 0.351–0.824), 0.568 (95% CI = 0.371–0.870), and 0.421 (95% CI = 0.260–0.679), respectively. Attaining higher MPR thresholds resulted in larger reductions in direct medical charges, excluding GA and other MS-related drugs. MPR of 0.25 was associated with $1699 lower 2-year total direct medical charges (p = 0.009) while a threshold of 0.95 was associated with $2136 lower total charges (p < 0.001), compared to patients not reaching these respective thresholds. MPR of 0.90 was associated with $986 lower MS-related charges than for those with MPR < 0.90 (p = 0.050). Results also revealed an association between patient adherence to GA and statistically significant reductions in charges for specific components of care.

Limitations:

Results are generalizable only to patients with medical and prescription benefit coverage without regard for functional status.

Conclusions:

As adherence improved the odds of relapse decreased and charge offsets generally increased. Results suggest that, despite higher costs associated with increased usage of GA, patient outcomes are improved and there are cost-offsets associated with adherent use of GA.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is one of the most common diseases of the central nervous system, affecting an estimated 1.1–2.5 million individuals living with MS worldwideCitation1,Citation2. Approximately 400,000 individuals in the US currently have a diagnosis of MS, and an additional 200 people are diagnosed each weekCitation3. US prevalence estimates for MS have ranged from 58–177 per 100,000 persons, depending upon the geographic region studiedCitation4–7. The disease is more common in more northerly geographical areas of the country, as well as among women and non-HispanicsCitation8–11.

The socioeconomic burden of MS is substantial, as the symptoms of the disease typically first strike patients between the ages of 20–40 years and may progress to total disability, thus potentially negatively affecting productivity, employment, and quality-of-life over a period of many yearsCitation1,Citation10,Citation12. The annual combined direct and indirect costs of MS in the US in 2004 have been estimated to be an average of $47,215 per diagnosed individual (estimated as $59,142 if converted to 2010 dollars), with 53% of these costs attributable to direct medical and non-medical costs, 37% to lost productivity, and 10% to informal careCitation13. A study of data from the calendar year 2004 reported the annual direct medical costs of MS to be an average of $12,879 per patientCitation14, while a more recent study in 2010 reported 12-month direct healthcare costs to be an average of $14,791 higher for an MS patient than for an individual in a ‘healthy comparison’ group (p < 0.001)Citation12. The 2010 study found significantly higher medical resource use among the MS patients, who were 3.5-times as likely to be hospitalized (15.2% vs 4.3% for MS vs comparison, respectively), twice as likely to have at least one emergency room (ER) visit (25.5% vs 12.2%) and 2.4-times as likely to have at least one visit for physical, occupational, or speech therapy (23.7% vs 9.9%; p < 0.001 for all comparisons)Citation12.

Although no cure for MS currently exists, beta interferons (Betaseron; Avonex; Rebif) and glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) have been identified as disease-modifying therapies and are available as first-line treatments for relapsing forms of the diseaseCitation15–17. Glatiramer acetate has been shown in both the randomized clinical trials and the open-label long-term follow-up studies to reduce the frequency of MS-related relapses, slow disease progression, and improve health-related quality-of-life, while being generally well toleratedCitation15,Citation18–25. Clinical trial results have found similar relapse rates when comparing glatiramer acetate to interferon beta-1a SCCitation26 and interferon beta-1bCitation27, and retrospective analyses have found a significantly higher medication possession ratio associated with interferon beta-1a IM compared to glatiramer acetateCitation28. In contrast, a prospective, open label study found that relapse reduction was significantly higher and discontinuation rates were significantly lower for patients treated with glatiramer acetate compared to those treated with beta interferonsCitation29. Similarly, retrospective studies have shown that glatiramer acetate is associated with a significantly lower probability of relapse and 2-year total direct medical costs compared to beta interferonsCitation30–32.

Despite the improved outcomes associated with glatiramer acetate, ‘[m]edicines will not work if you do not take them’Citation33, and poor treatment adherence is common among patients with MSCitation30. A recent analysis looked at the per patient level of adherence to glatiramer acetate therapy as determined by the medication possession ratio (MPR), which measures the percentage of days an individual received the medicationCitation28. The 2010 study reported the average patient MPR to be 0.698, meaning that, on average, MS patients in that study failed to take glatiramer acetate as prescribed ∼30% of the timeCitation28. This finding is consistent with that of Halpern et al.Citation34, who reported that the cohort of glatiramer acetate users possessed the drug, on average, 72% of the days observed. However, previous research on the use of disease modifying therapies for MS has found that adherence to medication at least 80% of the time is associated with a lower odds of relapse as well as significantly lower medical costsCitation35.

Poor adherence among MS patients has been found to result from a wide variety of factors. For example, lack of confidence in one’s ability to handle activities of daily living (ADLs) or to control disease symptoms that impact life activities, lack of injection competence, and adverse events have all been shown to impact adherenceCitation36–38. Furthermore, several studies have reported that a common reason for discontinuation of MS therapy is a lack of the patient’s understanding of the benefits of treatmentCitation39–42. It has been noted that the periods of remission characteristic of the disease course make it ‘impossible [for patients] to predict how their MS would affect them were they not on treatment’Citation39. The literature has therefore emphasized the importance of patient education, noting that MS patients should be apprised of ‘the potential benefits and risks of each treatment and the importance of adhering to their given treatment regimen’Citation39.

To educate patients regarding the importance of adherence, research is needed to demonstrate the relationship between medical outcomes and adherence levels. As one researcher has noted: ‘the true effect of poor adherence to MS therapy is not known, [although] it is likely to lead to a fall in treatment efficacy’Citation39. In response to this need for improved understanding, the authors conducted a retrospective, multivariate analysis among individuals with MS who were treated with glatiramer acetate to reveal the relationship between medication adherence and patient outcomes. Medication adherence in this study was defined as ‘the extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval and dose of and dosing regime’Citation43 and was measured by the medication possession ratio (MPR)Citation43–45. The results of this study are provided to help healthcare professionals understand and communicate the benefits of adherence to glatiramer acetate.

Methods

Data for this study were obtained from the i3 InvisionTM Data MartCitation46. This retrospective database is fully de-identified and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant. The database contains laboratory test results, hospitalization data, outpatient data, pharmacy data, and demographic information for more than 20 million de-identified individuals. The data collected spanned the period from January 1, 2006 through March 31, 2010.

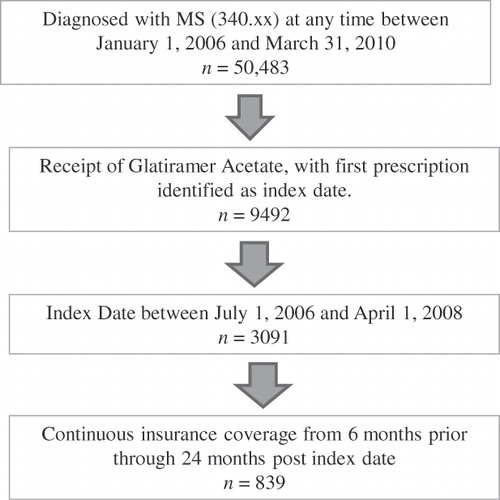

Patients were included in this study if they had a diagnosis code for multiple sclerosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] code of 340.xx) in any position and on any claim type, a procedure code, HCPCS code J1595 or outpatient pharmacy claim for glatiramer acetate injection (with the first such date identified as the index date), and insurance coverage extending continuously from 6 months before through 24 months after the index date. In addition, given the length of the pre- and post-periods as well as the data collection period, the index date was required to be between July 1, 2006 and April 1, 2008. A total of 839 individuals fit all inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included in the analysis ().

The focus of this study was to examine the relationship between medication adherence and patient outcomes. Using an intent-to-treat analysis, the medication possession ratio (MPR) was used as a measure of adherence for glatiramer acetate and was calculated as the number of days a supply of glatiramer acetate was available in the post-period divided by the number of days in the post-periodCitation44,Citation45,Citation47. When calculating MPR, the days supply of glatiramer acetate was calculated as the sum of days supplied associated with outpatient prescription use of the drug plus an addition of 1 day whenever an inpatient or outpatient procedure code of J1595 was found. This calculation allows the authors to include outpatient prescriptions, injections received in a physician’s office, as well as injections received when hospitalized in the total days supply of medication. By excluding the cost of MS medication, the study is therefore able to directly estimate charge offsets associated with improved compliance to glatiramer acetate. The major outcomes of interest were probability of relapse as well as total and MS-related charges in the post-period. Consistent with previous research, relapse was defined over the entire post-period as either an inpatient claim (hospitalization) with a listed diagnosis of MS or a claim for an outpatient visit with a listed diagnosis of MS in combination with a pharmacy or medical claim (within 7 days after the visit) for one of the following: intravenous methylprednisolone or corticotrophin or oral methylprednisolone, prednisone, prednisolone, or dexamethasoneCitation46. This analysis examined the association between adherence and medical charges absent the charge associated with glatiramer acetate, since, by construction, total charges for glatiramer acetate increase as adherence increases. Total charges were thus calculated as the sum of all direct medical charges other than the charge associated with use of glatiramer acetate over the entire 2 year post-period, while MS-related medical charges were calculated for all claims with an accompanying diagnosis of MS, with the exception of the charges associated with the use of glatiramer acetate. Components of both total charges and total MS-related charges were also examined, including inpatient, outpatient, emergency room (ER), and non-MS related drug charges. All medical charges were converted to 2010 values using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index.

A series of multivariate analyses were used to investigate the link between patient outcomes and various MPR thresholds (0.10, 0.25, 0.50, 0.70, 0.80, 0.90, and 0.95), while controlling for patient demographic characteristics (age, sex, region of residence, and type of insurance coverage) as well as co-payment amount associated with initial prescription for glatiramer acetate. By estimating a series of regressions with various MPR thresholds, the authors were able to observe the effect of changes in the MPR on patient outcomes and to avoid designating artificially a single threshold for ‘adherence’. A logistic regression was used to examine the impact of adherence on the probability of relapse in the 2-year post-period, while charges were estimated using a generalized linear model with gamma distribution and log link. In all cases the multivariate analyses controlled for patient demographic characteristics. The authors conducted all analyses using SAS Version 9.2. Findings of a p-value ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

presents the descriptive statistics for the individuals included in the study. Among the 839 individuals included in this cohort, the mean age was 45 years, 81% were female, and the majority were insured with a point-of-service provider (67%), exclusive provider organization (14%), or a health maintenance organization (12%). Consistent with the database as a whole where 46.18% of the population is from the South, the majority of patients in the authors’ MS cohort (45.65%) reside in the South. The mean 2-year total direct medical charges were $52,749 (SD = $78,449). Mean 2-year total MS-related charges were $24,415 (SD = $46,243). The mean probability of a relapse in the 2-year post period was 13%.

Table 1. Patient characteristics (n = 839).

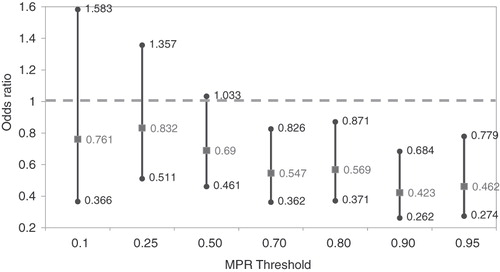

presents the effects of reaching alternative MPR thresholds on the probability of relapse. After controlling for patient characteristics, this analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in the individual’s probability of relapse for patients who reached the three lowest levels of MPR (0.10, 0.25, and 0.50), compared to patients who did not meet such thresholds. However, patients who had an MPR of at least 0.7 had a significantly lower probability of relapse in the 2-years after the initiation of glatiramer acetate therapy (odds ratio = 0.547, 95% CI = 0.362–0.826) compared to patients whose adherence was less than 0.7. The odds of relapse were also significantly lower for patients who achieved MPR thresholds of 0.80 (OR = 0.569; 95% CI = 0.371–0.871), 0.90 (OR = 0.423; 95% CI = 0.262–0.684), or 0.95 (OR = 0.462; 95% CI = 0.274–0.779), compared to those patients who did not meet these respective thresholds. As adherence increased, the odds of relapse generally declined.

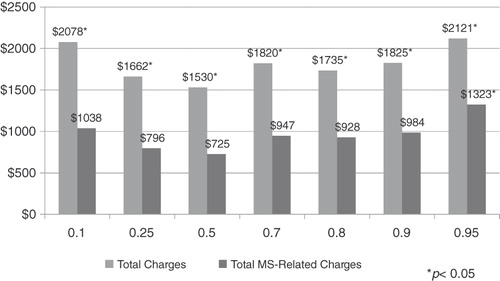

focuses on the association between the MPR and 2-year direct total and MS-related medical charges. After controlling for patient demographic characteristics and abstracting from prescription drug charges, medication adherence, as measured by alternative MPR thresholds, was associated with significantly lower 2-year total direct medical charges. For example, patients who attained a MPR threshold of at least 0.25 had $1662 lower 2-year direct medical charges (p = 0.0108), compared to patients with an MPR less than 0.25, while patients who had an MPR of at least of 0.95 had $2121 lower charges (p = 0.002) compared to patients with a less than 0.95 MPR. When examining total MS-related charges and abstracting from those charges associated with the MS drugs, results revealed charge offsets occur at an MPR threshold of 0.95. Specifically, patients with an MPR of at least 0.95 had $1323 lower MS-related charges (p = 0.013) compared to patients whose MPR was less than 0.95. In general, as the MPR threshold increased, the charge-offset associated with ‘being adherent’ increased. However, such charge offsets do not offset the charge associated with the use of glatiramer acetate, which was found to be, on average, $42,366 over the 2 year post-period.

While examines the association between adherence and total charges or total MS-related charges, and examine components of the total charges. reveals that patients with an MPR of at least 0.5 had significantly lower total inpatient and ER charges, compared to individuals who did not reach such a threshold. As the MPR threshold increased, the impact of MPR on both these components generally became larger. For example, patients with an MPR of at least 0.50 had $3370 lower inpatient charges (p = 0.002) than patients with an MPR of less than 0.50, while patients with a MPR threshold of at least 0.95 had $8507 lower inpatient charges (p < 0.001) than those patients with an MPR less than 0.95. Results also revealed that for all adherence levels greater than or equal to 0.25 patients who met the respective threshold had statistically significantly lower total outpatient charges compared to those who did not meet the respective threshold. There was no statistically significant relationship between adherence to glatiramer acetate and non-glatiramer acetate related total prescription drug charges. While examined components of total charges, examined the relationship between adherence and MS-related charges. Results revealed achievement of an MPR of 0.5 or higher to be associated with significantly lower MS-related inpatient charges compared to patients with an MPR of less than 0.5, while patients who achieved an MPR of at least 0.95 had significantly lower MS-related outpatient charges compared to those patients with an MPR of less than 0.95. There was no statistically significant relationship between patient adherence and MS-related ER charges.

Table 2. Association between alternative MPR threshold and total charge components.*

Table 3. Association between alternative MPR threshold and MS-related total charge components.*

Discussion

This retrospective, multivariate analysis of patients with MS explored the relationship between various medical outcomes (relapse rates, total medical charges, and MS-related charges) and alternative levels of adherence to the drug glatiramer acetate. The findings of this study showed that achieving minimum thresholds of adherence were associated with better outcomes, with the minimum thresholds varying according to the specific outcomes measured. In addition, there was a generally positive association between patient outcomes and adherence as it increased beyond the minimum threshold.

According to the results of this study, patients who took glatiramer acetate as prescribed at least 70% of the time (MPR ≥ 0.70) had significantly lower odds of relapse (odds ratio = 0.547, 95% CI = 0.362–0.826), while patients who achieved at least a 90% adherence level (MPR ≥ 0.90) had the lowest odds of relapse (OR = 0.423; 95% CI = 0.262–0.684). These findings, combined with the evidence from previous studies that the average MPR of MS patients taking glatiramer acetate is ∼70% (MPR = 0.698) indicate that MS patients taking glatiramer acetate are generally adherent enough to lower their chances of relapse but not to achieve the lowest possible odds of relapseCitation28,Citation34. These results indicate room for improvement in patient education, if the best possible therapeutic outcomes are to be achieved.

The results also have important implications for a value-based insurance design (VBID), whereby patients are required to pay lower co-payments for cost-saving therapiesCitation48. While VBID has been gaining acceptance with employers, it has largely been confined to common chronic conditions such as diabetes or hypertensionCitation49. These results suggest that VBID could also be applied to other chronic conditions such as multiple sclerosis.

This study is the first to measure the relationship between varying levels of adherence and outcomes among patients taking glatiramer acetate. However, recent studies have examined the effect of adherence to disease-modifying therapies using the commonly cited adherence threshold of MPR ≥ 0.80Citation34,Citation35. Halpern et al.Citation34 performed a retrospective administrative claims analysis to compare 12 months of adherence (MPR ≥ 0.80) among patients with multiple sclerosis who initiated treatment with glatiramer acetate and other disease-modifying therapies. The mean MPR for the glatiramer acetate cohort was 72% and 55.4% was adherent at the MPR ≥ 0.80 thresholdCitation34. Tan et al.Citation35 investigated adherence with the disease-modifying therapies collectively and its impact on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with MS. They found that ‘adherent’ (MPR ≥ 0.80) patients had significantly lower odds of relapse relative to the ‘non-adherent’ (MPR < 0.80) cohort (OR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.59–0.85), as well as significantly reduced medical costs ($3380, 95% CI = $3046–$3750 vs $4348, 95% CI = $3828–$4940, p = 0.003)Citation35. While these studies provided evidence of the importance of adherence, the arbitrary designation of a single adherence threshold limited the usefulness of the findings. As it has been noted, ‘the use of arbitrary categories of good and poor compliance (often set at 80%) [is] usually … unsupported by research’, and different disease states and medications may likely have different minimum adherence thresholdsCitation47. For instance, 95–100% adherence to highly active retroviral therapy has been found necessary to prevent the emergence of drug resistant HIV variants among patients with AIDS/HIV infectionCitation50, and patients less than 95% adherent to the therapy have been shown to be 3.5-times more likely to have treatment failure relative to those who are 95–100% adherentCitation51, while those who attain 95% or greater adherence to drug therapy had significantly lower hospitalization costsCitation52. Other disease states and medications have lower minimum adherence thresholds. For instance, studies among patients at risk for cardiovascular events have indicated that the ‘most consistent benefits’ of statin therapy occur at 80% or greater adherenceCitation53. Like all of this previous research, the authors’ analysis has shown a positive association between increased adherence and improved outcomes. However, unlike this research, their analysis has disproved any supposition of a single threshold clearly demarcating adherence vs non-adherence to glatiramer acetate therapy.

The charge findings, in particular, showed a wide range of alternative thresholds to be associated with different charge outcomes. For instance, glatiramer acetate therapy was shown to significantly lower total MS-related charges and MS-related outpatient charges only when patients achieved at least 95% adherence, although there was a trend to lower MS-related outpatient charges at a MPR of 0.70 and higher. These findings generally support the hypothesis that disease-specific outcomes generally improve progressively as adherence improves.

In other charge areas, significantly improved results were observed at lower adherence thresholds. For instance, MS-related inpatient charge-offsets were significant at an MPR threshold of at least 0.50. All-cause inpatient and ER charge-offsets were significant at an MPR of 0.50 or higher, while a MPR of at least 0.25 was associated with significant all-cause outpatient charge offsets. One possible explanation for the lower adherence threshold associated with all-cause outpatient charge-offsets compared to the MS-related outpatient charge-offsets might be that there was a reduction in all-cause outpatient care related to co-morbidities with low levels of adherence, while the MS-related care did not reach statistical levels of difference until adherence was high. Notably, however, both all-cause and MS-related charges offsets generally increased as adherence improved beyond the minimum threshold. These charge offsets with improved adherence were, in some cases, substantial. For example, while achievement of an MPR threshold of 0.50 was associated with $3370 lower inpatient charges (p = 0.002), an MPR threshold of at least 0.95 was associated with $8507 lower inpatient charges (p < 0.001).

As with any research, the findings of this study should be interpreted within the context of the limitations of the study’s design. First, this analysis was conducted using an administrative claims database and included only patients with medical and prescription benefit coverage. It may not be possible, therefore, to generalize from these results to other populations. Second, it is less rigorous to rely upon diagnostic codes rather than upon formal diagnostic assessments for identifying patients. Third, the use of medical claims data precludes the use of patient assessments; as a result, the analysis is unable to include such factors as patients' income or caregiver support that may also be associated with adherence. Furthermore, the database does not distinguish between primary and non-primary diagnostic and procedure codes. Finally, the main analysis examined the relationship between adherence and direct medical charges absent the charge associated with glatiramer acetate, since, by construction, total charges for glatiramer acetate increase as adherence increases. Inclusion of the charges associated with glatiramer acetate resulted in higher charges as adherence improved, although charge-offsets also generally increased with improvements in adherence. In addition, the analysis does not include indirect costs, which have been shown to be large for patients with MSCitation13,Citation54. However, a richer dataset would be necessary to explore the indirect costs associated with MS relapses, including the relative impacts of lost work time, unemployment, the increased use of other medical care services, and other intangible costs.

Conclusions

The results of this retrospective, multivariate analysis indicate that patients who took glatiramer acetate as prescribed at least 70% of the time had significantly lower odds of relapse, while those who achieved at least a 90% adherence level had even lower odds of relapse and lower total MS-related charges absent the charges for drug. An adherence threshold of at least 25% was associated with lower 2-year direct medical charges and lower all-cause outpatient charges, while an adherence threshold of at least 50% was required to decrease all-cause inpatient, MS-related inpatient, or all-cause ER charges. Both all-cause and MS-related charges typically decreased progressively as adherence improved beyond a minimum threshold, which varied based on the particular outcome examined.

It should be noted that greater levels of adherence necessarily imply increased use of glatiramer acetate, and hence significantly higher MS-related drug charges. However, this would not alter the basic finding of reductions in incremental charges of other healthcare resource categories as MPR rises and adherence improves. Moreover, the benefits from adherence shown here pertain to direct medical charges. Increased productivity is an additional benefit that would be accrued to patients and their caretakers as relapses are reduced, and less time is invested in utilization of inpatient and outpatient services. While these additional savings are not observable from insurance claims data used in this analysis, this should be taken into account in formulating coverage policies for disease-modifying therapies used in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Indeed, this study supports a large body of research, conducted with different patients, diseases, and medications, which has shown that better adherence leads to better outcomes for patients, the healthcare system, and society at largeCitation50–53,Citation55–59. At the same time this study is the first to measure the relationship between varying levels of adherence and outcomes among multiple sclerosis patients taking glatiramer acetate, as well as to examine the incremental cost offsets associated with improved adherence.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Teva Pharmaceuticals and two employees of the sponsor participated in developing the research question and the methods for analysis, reviewing and interpreting study results as well as reviewing and approving this manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

M.O.-B. and J.C.-H. are employees of Teva Pharmaceuticals. A.D. and M.L. were paid consultants to Teva Pharmaceuticals on this research project.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Patricia Platt for her help in drafting the manuscript.

References

- Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. World of MS - About MS - Introduction. 2011. Available at: http://www.msif.org/en/about_ms/index.html. Accessed January 7, 2011

- Pugliatti M, Sotgiu S, Rosati G. The worldwide prevalence of multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2002;104:182-91

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Who gets MS?: National MS Society. 2011. Available at: http://www.nationalmssociety.org/about-multiple-sclerosis/what-we-know-about-ms/who-gets-ms/index.aspx. Accessed January 7, 2011

- Anderson DW, Ellenberg JH, Leventhal CM, et al. Revised estimate of the prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the United States. Ann Neurol 1992;31:333-6

- Baum HM, Rothschild BB. The incidence and prevalence of reported multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 1981;10:420-8

- Noonan CW, Kathman SJ, White MC. Prevalence estimates for MS in the United States and evidence of an increasing trend for women. Neurology 2002;58:136-8

- Williamson DM, Henry JP. Challenges in addressing community concerns regarding clusters of multiple sclerosis and potential environmental exposures. Neuroepidemiology 2004;23:211-16

- Beretich BD, Beretich TM. Explaining multiple sclerosis prevalence by ultraviolet exposure: a geospatial analysis. Mult Scler 2009;15:891-8

- Noonan CW, Williamson DM, Henry JP, et al. The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in 3 US communities. Prev Chronic Dis 2010;7:12. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jan/08_0241.htm. Accessed June 22, 2011

- Stuve O. Multiple Sclerosis Overview - GeneReviews - NCBI Bookshelf. 2010. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1316/?log$=disease_name. Accessed January 7, 2011

- Alonso A, Hernán MA. Temporal trends in the incidence of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Neurology 2008;71:129-35

- Asche CV, Singer ME, Jhaveri M, et al. All-cause health care utilization and costs associated with newly diagnosed multiple sclerosis in the United States. J Manag Care Pharm 2010;16: 703-12

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Atherly D, et al. Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study in the United States. Neurology 2006;66:1696-702

- Prescott JD, Factor S, Pill M, et al. Descriptive analysis of the direct medical costs of multiple sclerosis in 2004 using administrative claims in a large nationwide database. J Manag Care Pharm 2007;13:44-52. Available at: http://www.amcp.org/jmcphome.aspx. Accessed June 22, 2011

- Jongen PJ, Lehnick D, Sanders E, et al. Health-related quality of life in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis patients during treatment with glatiramer acetate: a prospective, observational, international, multi-centre study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:133. Available at: http://www.hqlo.com/content/8/1/133. Accessed June 21, 2011

- Mäurer M, Dachsel R, Domke S, et al. Health care situation of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis receiving immunomodulatory therapy: a retrospective survey of more than 9000 German patients with MS. Eur J Neurol 2011; 18:1036-45

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Treatments: National MS Society. 2010. Available at: http://www.nationalmssociety.org/about-multiple-sclerosis/what-we-know-about-ms/treatments/index.aspx. Accessed January 7, 2011

- Ford C, Goodman AD, Johnson K, et al. Continuous long-term immunomodulatory therapy in relapsing multiple sclerosis: results from the 15-year analysis of the US prospective open-label study of glatiramer acetate. Mult Scler 2010;16:342-50

- Ford CC, Johnson KP, Lisak RP, et al. A prospective open-label study of glatiramer acetate: over a decade of continuous use in multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler 2006;12:309-20

- Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Cohen JA, et al. Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology 1995;45:1268-76

- Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Cohen JA, et al. Extended use of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) is well tolerated and maintains its clinical effect on multiple sclerosis relapse rate and degree of disability. Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology 1998;50:701-8

- Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Ford CC, et al. Sustained clinical benefits of glatiramer acetate in relapsing multiple sclerosis patients observed for 6 years. Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Mult Scler 2000;6:255-66

- Ge Y, Grossman RI, Udupa JK, et al. Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) treatment in relapsing-remitting MS: quantitative MR assessment. Neurology 2000;54:813-7

- Martinelli Boneschi F, Rovaris M, Johnson KP, et al. Effects of glatiramer acetate on relapse rate and accumulated disability in multiple sclerosis: meta-analysis of three double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Mult Scler 2003;9:349-55

- Carter NJ, Keating GM. Glatiramer acetate: a review of its use in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and in delaying the onset of clinically definite multiple sclerosis. Drugs 2010;70:1545-77

- Mikol DD, Barkhof F, Chang P, et al. Comparison of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a with glatiramer acetate in patients with relapseing multiple sclerosis (the REbif vs Glatiramer Acetate in Relapsing Disease [REGARD] study): a multicentre, randomised, parallel, open trial. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:903-14

- O'Connor P, Filippa M, Arnason B, et al. 250 µg interferon beta-1b versus 20 mg glatiramer acetate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:889-97.

- Kleinman NL, Beren IA, Rajagopalan K, et al. Medication adherence with disease modifying treatments for multiple sclerosis among US employees. J Med Econ 2010;13:633-40

- Haas J, Firzlaff M. Twenty-four-month comparision of immunomodulatory treatments - a retrospective open label study in 308 RRMS patients treated with beta interferons or glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®). Eur J Neurol 2005;12:425-31

- Castelli-Haley J, Oleen-Burkey M, Lage MJ, et al. Glatiramer acetate versus interferon beta-1a for subcutaneous administration: comparison of outcomes among multiple sclerosis patients. Adv Ther 2008;25:658-73

- Castelli-Haley J, Oleen-Burkey MA, Lage MJ, et al. Glatiramer acetate and interferon beta-1b: a study of outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther 2009;26:552-62

- Castelli-Haley J, Oleen-Burkey MA, Lage MJ, et al. Glatiramer acetate and interferon beta-1a for intramuscular administration: a study of outcomes among multiple sclerosis intent-to-treat and persistent-use cohorts. J Med Econ 2010;13:464-71

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. 2011. Available at: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en/index.html. Accessed February 7, 2011

- Halpern R, Agarwal S, Dembek C, et al. Comparison of adherence and persistence among multiple sclerosis patients treated with disease-modifying therapies: a retrospective administrative claims analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2011;5:73-84 Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S15702. Accessed June 21, 2011

- Tan H, Cai Q, Agarwal S, et al. Impact of adherence to disease-modifying thereapies on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther 2011;28:51-61

- Fraser C, Hadjimichael O, Vollmer T. Predictors of adherence to Copaxone therapy in individuals with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs 2001;33:231-9

- Fraser C, Morgante L, Hadjimichael O, et al. A prospective study of adherence to glatiramer acetate in individuals with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs 2004;36:120-9

- Zwibel H, Pardo G, Smith S, et al. A multicenter study of the predictors of adherence to self-injected glatiramer acetate for treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2010;258:402-11

- Patti F. Optimizing the benefit of multiple sclerosis therapy: the importance of treatment adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence 2010;4:1-9. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S8230. Accessed June 21, 2011

- Clerico M, Barbero P, Contessa G, et al. Adherence to interferon-beta treatment and results of therapy switching. J Neurol Sci 2007;259:104-8

- Río J, Porcel J, Téllez N, et al. Factors related with treatment adherence to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2005;11:306-9

- Tremlett HL, Oger J. Interrupted therapy: stopping and switching of the beta-interferons prescribed for MS. Neurology 2003;61:551-4

- International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. ISPOR medication compliance and persistence SIG accomplishments. 2011 Available at: http://www.ispor.org/sigs/mcp_accomplishments.asp. Accessed January 9, 2011

- Mattke S, Jain AK, Sloss EM, et al. Effect of disease management on prescription drug treatment: what is the right quality measure? Dis Manag 2007;10:91-100

- Cantrell CR, Eaddy MT, Shah MB, et al. Methods for evaluating patient adherence to antidepressant therapy: a real-world comparison of adherence and economic outcomes. Med Care 2006;44:300-3

- Chastek BJ, Oleen-Burkey M, Lopez-Bresnahan MV. Medical chart validation of an algorithm for identifying multiple sclerosis relapse in healthcare claims. J Med Econ 2010;13:618-25 doi: 10.3111/13696998.2010.523670

- Cramer J, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008;11:44-7. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x/pdf. Accessed June 22, 2011

- Chernew ME, Rosen AB, Fendrick AM. Value-based insurance design. Health Affairs 2007;26:w195-w203. Available at: http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/26/2/w195.full. Accessed June 22, 2011

- Encinosa WE, Bernard D, Dor A. Does prescription drug adherence reduce hospitalizations and costs? The case of diabetes. Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res 2010;22:151-73

- Chesney M. Adherence to HAART regimens. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2003;17:169-77

- Ickovics JR, Cameron A, Zackin R, et al. Consequences and determinants of adherence to antiretroviral medication: results from Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol 370. Antivir Ther (Lond) 2002;7:185-93

- Valenti WM. Treatment adherence improves outcomes and manages costs. AIDS Read 2001;11:77-80

- Simpson RJ, Mendys P. The effects of adherence and persistence on clinical outcomes in patients treated with statins: a systematic review. J Clin Lipidol 2010;4:462-71

- Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan FA, Goldstein LB, et al. A comprehensive assessment of the cost of multiple sclerosis in the United States. Mult. Scler 1998;4:419-25

- Baros AM, Latham PK, Moak DH, et al. What role does measuring medication compliance play in evaluating the efficacy of naltrexone? Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007;31:596-603

- Hansen R, Seifeldin R, Noe L. Medication adherence in chronic disease: issues in posttransplant immunosuppression. Transplant Proc 2007;39:1287-300

- Nelson MR, Reid CM, Ryan P, et al. Self-reported adherence with medication and cardiovascular disease outcomes in the Second Australian National Blood Pressure Study (ANBP2). Med J Aust 2006;185:487–9. Available at: http://www.mja.com.au/public/issues/185_09_061106/contents_061106.html. Accessed June 22, 2011

- Schectman JM, Nadkarni MM, Voss JD. The association between diabetes metabolic control and drug adherence in an indigent population. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1015–21. Available at: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/25/6/1015.full.pdf+html. Accessed June 22, 2011

- Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK. Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:805–11. Available at: http://psychservices.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/52/6/805. Accessed June 22, 2011