Abstract

Objective:

This retrospective patient data analysis was initiated to describe current treatment patterns of patients in Germany with arterial hypertension, with a special focus on compliance, persistence, and medication costs of fixed-dose and unfixed combinations of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), amlodipine (AML) and hydrochlorothiazide (HCT) in Germany.

Methods:

The study analyzed prescription data collected by general practitioners, using the IMS Disease Analyzer database. The database was searched for patients with the diagnosis hypertension (ICD-10 code I10) and treatment data in the period 09/2009 to 08/2010. Compliance was measured indirectly based on the medication possession ratio (MPR), and persistence was defined as the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy. Medication costs were assessed from the statutory health insurance perspective in Germany.

Results:

In the IMS DA 406,888 observable patients in Germany were encoded with the diagnosis I10 essential hypertension. In total, 88,716 patients received prescriptions including ARBs, monotherapy (18.6%) or unfixed combinations with other anti-hypertensives (19.3%). The compliance with fixed-dose combinations of ARB with HCT, either dual or with one other anti-hypertensive drug, was significantly better, compared to unfixed combinations (mean compliance 78.1% for fixed-dose vs 71.5% for unfixed combinations of ARB with HCT, p < 0.0001; mean compliance 79.4% vs 72.0%, p < 0.0001 if an additional anti-hypertensive medication was added). Fixed-dose combinations of ARB with HCT, ARB with AML, dual only or prescribed with another anti-hypertensive medication resulted in a substantial increase of persistence, especially for patients on fixed-dose dual combinations (225.7 vs 163.6 days for ARB with HCT; 232.9 vs 178.4 days for ARB with AML, respectively). Fixed-dose combinations (varying from €1.38 to €2.20 per patient and day) were on average cheaper than unfixed combinations.

Limitations:

Persistence and compliance could be under- or over-estimated because their assessment was based on prescription information. For two thirds of 69,060 patients, data on compliance and persistence was missing.

Conclusion:

The study shows considerable variations in ARB treatment patterns among patients, with the majority of patients treated with fixed-dose or semi-fixed combination therapy. Fixed-dose combinations of ARBs with HCT and/or AML seem to result in better compliance and persistence compared to unfixed regimes of these drug classes, leading to reduction in all-cause hospitalizations, emphasizing the benefit and potential cost-savings of using fixed-dose regimes in a real-life general practice setting in Germany.

Keywords::

Introduction

Hypertension has a high global prevalence (>30% of the adult population) and is one of the most common modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD)Citation1. However, despite improvements in the management of hypertension, patients with hypertension worldwide are not achieving the therapeutic goal of normalised blood pressure (BP), being below 140/90 mmHg. Less than half of treated patients achieve adequate BP controlCitation2. According to recent estimates, the prevalence of hypertension in Germany is ∼55% and accounts for about one quarter of the total mortality in GermanyCitation3. Given the high prevalence, the economic burden of hypertension is substantial (€24,127 million) and is projected to further increase due to an aging population. The presence of co-morbid conditions in patients with hypertension, such as diabetes, further escalates the burdenCitation4.

Current evidence indicates that treating BP to goal is highly cost-effective, cost-saving and thus essential for reducing the healthcare burden of hypertension and its associated co-morbiditiesCitation2. The BP lowering effect of medication is ideally supported by smoking cessation, weight reduction, moderate alcohol consumption, physical activity, reduction of salt intake and increase in fruit and vegetable intake and decrease in saturated and total fat intake. A variety of different medications from multiple classes allows the physician to address diverse patient profiles and preferencesCitation5. The reappraisal paper by Mancia et al.Citation6 for the Management of Arterial Hypertension supports the use of combination therapy, particularly in complicated or uncontrolled patients. According to Mancia et al.Citation6, fixed-dose combinations of two drugs in a single tablet should be used to simplify the treatment regime. The combination of an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), a calcium channel blocker (CCB) and a diuretic is among rational three-drug combination approachesCitation6. Clinical evidence demonstrates that combinations reduce BP faster and are more effective than monotherapyCitation7–12. The findings show that when agents with different mechanisms of action are combined, their effects appear to be additiveCitation13. In particular, the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) guidelines refer to trial evidence of outcome reduction for the combination of a diuretic with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or an ARB or a CCB, an ACEI/CCB combination and an ARB/CCB combinationCitation14. In no less than 15–20% of hypertensive patients, three drugs are required to achieve BP control. The ESH guidelines and the German Guidelines for Treatment of Hypertension, which are based on the ESH guidelines, suggest the most rational combination of an ARB, a CCB and a diuretic at effective dosesCitation6,Citation14,Citation15.

Previous studies show that fixed-dose combinations have a higher treatment compliance and persistence in comparison to unfixed combinationsCitation16–22. ARBs have the highest rate of treatment persistence and compliance among anti-hypertensivesCitation23–26. For a successful management of hypertension, and other chronic conditions, compliance and persistence are important. In addition, compliance and persistense have an impact on drug acquisition costs and healthcare resource utilization associated with drug side-effects and the consequences of an untreated conditionCitation20,Citation21,Citation27,Citation28. Bramlage and HasfordCitation27 showed that patients are more persistent and have a higher BP lowering effect with ARBs in comparison to any other drug class. Moreover, recently developed drugs have a higher price per tablet than older ones, but result in a more favourable cost-to-effect ratio when direct drug costs and indirect costs are considered. According to Bramlage and HasfordCitation27 ARBs provide substantial cost savings and may prevent cardiovascular morbidity and mortality based on the more complete anti-hypertensive coverage.

Based on recent publicationsCitation20–22,Citation29–33 suggesting better compliance and persistence among patients receiving fixed-dose anti-hypertensive regimens it was considered to investigate whether patients in Germany who receive a fixed-dose combination of ARB with a CCB (amlodipine [AML]) and a diuretic (hydrochlorothiazide [HCT]) demonstrate better compliance and better persistence with their therapy regime and generate lower medication costs compared to patients on an unfixed combination regime. This is the first study in Germany which would provide this important information based on real-world data from physicians practices.

Objectives

This retrospective patient data analysis was initiated to describe current treatment patterns of patients in Germany with hypertension, with a special focus on compliance, persistence, and medication costs of fixed-dose and unfixed combinations of ARB, AML, and HCT in Germany.

Methods

Study database

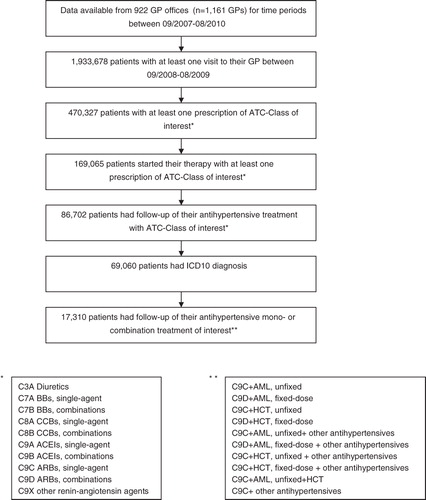

This retrospective study analyzed prescription data collected by general practitioners (GPs), using a longitudinal database, the German IMS Disease Analyzer (DA)Citation34. The DA database of IMS Health provides access to a representative panel of physicians and patients, validated, and suitable for pharmacoepidemiological and pharmacoeconomic studiesCitation34. For this study, data were used from 922 GP practices in Germany. Al drug prescriptions, indication of prescribing, diagnoses, and basic demographic data were routinely recorded in the physician’s computer system and centrally assembled by IMS. The DA database was searched for patients with the diagnosis hypertension (ICD-10 code I10) and treatment data for period 09/2009 to 08/2010 and prescriptions of ARBs, as single-agents or in combination (fixed-dose or unfixed) with other anti-hypertensive drugs (e.g., diuretics, CCBs, beta-blockers [BBs], ACEIs). For analysis of persistence and compliance, the period 09/2008 to 08/2009 was searched for eligible patients to ensure availability of data for at least 12 months. MPR was estimated over a 1-year period. Following the methodology in the article by Hasford et al.Citation25, end of persistence was defined as no repeat anti-hypertensive drug prescription for more than 6 months and was calculated as the day of the last prescription minus the day of the treatment initiation. The compliance and persistence measurements were both chosen in order to maintain a rich understanding of the medication-taking behavior of patients with hypertension (35). The data were anonymized and processed in accordance with the German safety regulations.

Definitions

Compliance and persistence were defined according to the definitions of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Medication Compliance and Persistence Workgroup. Compliance was defined as ‘the extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval and dose of a dosing regimen’Citation35. Compliance was measured indirectly based on the medication possession ratio (MPR), calculated as number of days supplied within the refill interval in relation to the number of days in the refill intervalCitation36.

Patients were sub-divided into three compliance categories based on Rasmussen et al.Citation37: high (proportion of days covered ≥80%), intermediate (40–79%), and low (<40%). Persistence was defined as ‘the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy’Citation35, and the proportion of patients who remained persistent on their initially prescribed therapy at 1 year was calculated as well. Patients, who started on their initial regimen, being treated for less than 1 year, discontinuing their therapy and switching to the other regimen, were also considered for the analyses on persistence. Patients who were lost to follow-up within 1 year from starting their initial regimen were not considered for the analyses. Fixed-dose combination regimen was defined as a combination of anti-hypertensive drugs in a single tablet. Unfixed combination was defined as an administration of anti-hypertensive drugs via separate tablets. Semi-fixed combination was defined as an administration of anti-hypertensive drugs combined in a single tablet together with single agents administered separately. Hospitalizations referred to any-cause hospitalizations, and referrals included any referrals to healthcare professionals (i.e., visits to GPs as well as specialists).

Assessment of costs

Medication costs were based on 2010 pharmacy retail prices in Germany and reported in Euros (€). Average medication costs for anti-hypertensive treatment were assessed per patient and day.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive analysis presented absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. The difference between mean persistence values (days) was calculated by using multiple regression analysis, adjusted for age, gender, insurance status, and co-morbidities. The level of statistical significance was set at ≤0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

The data of 406,888 patients with the diagnosis I10 essential hypertension were obtained from 922 GP practices in Germany (1161 physicians) and evaluated for this study. Basic information regarding the patients studied is summarized in . Patients were on average 64.9 years old (SD = 14.3), predominantly female (53.9%), publicly insured (92.1%), and ∼9.3% of patients were hospitalized during the study period (). The co-morbid conditions most frequently encountered in the patient sample were disorders of lipoprotein metabolism (26.3%), diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2) (22.4%), back pain (19.1%), and chronic ischemic heart disease (14.7%).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Treatment pattern

For 347,619 patients (85%) at least one prescription of anti-hypertensive medication (Anatomical Therapeutic Classification System of the European Pharmaceutical Research Association [ATC] level 3 codes) was documented for the period between September 2009 and August 2010 ().

Table 2. Prescriptions of anti-hypertensive drugs.

In our study, BBs were prescribed for 55.1% of the patients on treatment for hypertension, 56.7% received ACEIs, 27.3% received ARBs, 28.0% received diuretics, and 27.6% received prescriptions for CCBs aimed at controlling their BP (). Among patients receiving ARBs, unfixed or fixed-dose combinations (n = 88,716), the proportions of patients were similar among those on unfixed combinations with ARBs, monotherapy (18.6%), or unfixed combinations with other anti-hypertensives (19.3%); fixed-dose double combinations of ARB with HCT only (18.9%); or together with other anti-hypertensives, i.e., semi-fixed triple combinations (19.5%) ().

Table 3. Prescriptions of ARBs.

Among patients receiving fixed-dose and unfixed combinations of ARB, AML, and HCT in Germany, differences regarding sociodemographics and resource utilization were noted (). For example, patients on unfixed regimen tended to be older than those receiving prescriptions for fixed-dose dual or triple combinations of ARB, AML, and/or HCT. In addition, the percentage of patients with co-morbidities, referrals, and hospitalizations in the period 09/2009–08/2010 was higher among patients on unfixed dual combinations of ARB with either HCT or AML. The percentages of patients with co-morbidities among patients on fixed-dose triple combinations of ARB, AML, and HCT were higher compared to patients on unfixed triple combinations of the mentioned medications, also reflected by the higher percentage of patients on fixed-dose triple combinations with referrals to healthcare professionals (81.9%) in the period 09/2009–08/2010 (). Patients on a non-fixed-dose triple regimen of ARB, AML, and HCT in this period were almost twice as likely to be hospitalized due to any cause (15.3%) compared to the patients on a fixed-dose triple regimen (8.4%) ().

Table 4. Characteristics of patients with prescriptions of ARBs: monotherapy, fixed and non-fixed combinations.

Compliance and persistence

There were 69,060 patients with hypertension who were initiated on different ATC classes of anti-hypertensive drugs in the period 09/2008–08/2009. The patients were on average 65.9 years old, predominantly female (55.5%), and publically insured (). Of 69,060 patients, 17,310 had at least 12-months follow-up data on ARB mono- or combination treatment with AML and/or HCT, which enabled assessment of the patients’ compliance and persistence with these treatment regimes ().

The mean compliance value with fixed-dose combinations ranged between 72.8% for ARB with AML and 79.4% for fixed-dose dual combination of ARB with HCT plus another anti-hypertensive drug (). In the unfixed combination regimes, compliance ranged between 71.5% for ARB and HCT, and 76.2% for ARB, AML, and another anti-hypertensive drug ().

Table 5. Compliance and persistence of patients who started treatment with fixed or non-fixed ARBs regimes between 08/2008–07/2009 and with data available for the following 12 months (n = 17,310).

The compliance with fixed-dose combinations of ARB with HCT, either dual or with one other anti-hypertensive drug, was significantly better, compared to unfixed combinations (mean compliance 78.1% for fixed-dose vs 71.5% for unfixed combinations of ARB with HCT, p < 0.0001; mean compliance 79.4% vs 72.0%, p < 0.0001 if an additional anti-hypertensive medication was added) (). Differences regarding compliance with fixed-dose vs unfixed combinations of ARB with AML, either dual only or with another anti-hypertensive drug, were not statistically significant (). Fixed-dose combinations of ARB with HCT, ARB with AML, dual only or prescribed with another anti-hypertensive medication, resulted in a substantial increase of persistence, especially for patients on fixed-dose dual combinations of ARB with HCT and ARB with AML compared to unfixed dual combinations of these regimes (225.7 vs 163.6 days for ARB with HCT; 232.9 vs 178.4 days for ARB with AML, respectively) ().

Medication costs

The average medication cost for fixed-dose and unfixed combinations of ARB, AML, and/or HCT treatment or other anti-hypertensives was calculated as €1.94 (SD = €3.68) per patient and day (). As shown in the table, the average per-patient daily costs were as follows: among elderly 2.00€ vs 1.83€ in aged <65 years, among men 1.97€ vs 1.92€ among women, and among DM2 patients 2.10€ vs 1.83€ per non-DM2 patient. Of these costs, the lowest costs were observed in the sub-group of patients aged <65 years (€1.83 [SD €3.18] per patient and day) and the highest costs in the sub-group of patients with DM2 (€2.10 [SD €4.18] per patient and day). Fixed-dose dual combinations of ARB and HCT were associated with lower per-patient daily costs compared to unfixed combinations (total and per sub-group) (). Fixed-dose dual combinations of ARB and AML were associated with lower per-patient daily costs for following sub-groups only: age <65 years, men, and non-DM2, compared to unfixed combinations ().

Table 6. Mean daily pharmacy costs (in €, 2010) for patients with fixed-dose or unfixed ARB prescriptions.

Discussion

Frequency and distribution of sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender) and major co-morbidities (e.g., DM2) in our patient population were similar to another study (multi-center, non-interventional, with 8123 arterial hypertension patients seen by physicians in Germany), by Schmieder et al.Citation38. This is an indication of the current study patient population to be representative of the hypertension patient population in Germany. The majority of patients in our database received prescriptions for ACEIs (56.7%), and the percentages of patients receiving prescriptions for ARBs, diuretics, and CCBs were approximately the same (27.3%, 28.0% and 27.6%, respectively). In the study by Schmieder et al.Citation38, at baseline, 54.7% of patients received prescriptions for ACEIs, 26.6.0% for ARBs, 50.3% for diuretics, and 31.7% received CCBs. Thus, not only regarding sociodemographic characteristics but also regarding prescription frequencies for ACEIs and ARBs our patient population was similarCitation37.

We showed differences regarding sociodemographics and resource utilization among patients receiving fixed-dose and unfixed combinations of ARB, AML, and HCT, in particular, higher resource utilization among patients on an unfixed regimen, who also tended to be older than those receiving prescriptions for fixed-dose dual or triple combinations. Our data has shown that hypertensive patients in Germany more often receive prescriptions for single agents (BBs, ACEIs, CCBs) than for the fixed-dose combinations of mentioned medication classes with other medications. A considerable percentage of patients with any ARB prescription were on monotherapy with ARBs (18.6%). These results reflecting real-world prescribing practices in Germany have to be balanced to the current European guidelines on hypertension treatment and when these recommend the combination of at least two drugs to control hypertensionCitation6.

Our results are in line with findings from prior studies assessing compliance and persistence in hypertensive patients suggesting that treatment with ARBs is associated with significantly higher compliance and persistence rates than other anti-hypertensive drugsCitation20,Citation21,Citation24,Citation25,Citation39–43. Persistence indicates that both the patient and the clinician are willing to continue with the drug regimenCitation24, and is especially important in treatment of hypertension, because the benefits of treating hypertension are achieved fully after at least 4 years of continuous treatment in a patientCitation44. In other words, little benefit can be expected for patients who discontinue their treatment or show lack of persistence with their anti-hypertensive therapyCitation24. We showed an increased compliance and persistence with fixed-dose combinations of ARBs with another anti-hypertensive drug, compared to unfixed combinations of these regimes. These findings confirm earlier study results of Yang et al.Citation21 in the US, showing a significantly better compliance and persistence among patients on fixed-dose combinations of anti-hypertensives including ARBs. Hasford et al.Citation25 reported the longest persistence with ARBs among patients on anti-hypertensive treatment. Bloom39, in a retrospective study of prescription records in the US, reported a substantially higher percentage of patients continuing therapy with ARBs after 12 months of follow-up, compared with ACEIs, CCBs, and other anti-hypertensive medications. Degli et al.Citation40 conducted a retrospective analysis of prescription records in the drugs database of Italy and found that ARBs led to a higher persistence rate compared to ACEIs, BBs, CCBs, and diuretics. Elliott et al.Citation41, in their retrospective analysis of a nationwide administrative claims database in the US, looked specifically at persistence and compliance with monotherapy using the most commonly dispensed agents among anti-hypertensive drug classes. They found that patients on ARB monotherapy demonstrate better persistence and higher MPR. Höer et al.Citation42 examined persistence and compliance among patients on anti-hypertensive drug therapy in the real-life setting of a German sickness fund, showing the highest persistence after the prescriptions with ARBs compared with other anti-hypertensive agents. In a recently conducted study in Germany, Mathes et al.Citation43 showed that the resource utilization in patients initiating monotherapy with ARBs is significantly lower compared to patients initiating therapy CCBs, ACEIs, and BBs. Fixed-dose dual combinations of ARBs in our study were associated not only with better compliance and persistence, but also with lower hospitalization rates and lower medication costs compared to unfixed combinations, regardless of age, gender, and diabetes status. These findings are consistent with other studiesCitation20,Citation21,Citation45–49 showing an inverse relationship between compliance with anti-hypertensive medication regimens and resource utilization as well as healthcare costs. For example, Yang et al.Citation21 showed that patients with fixed-dose combinations had less hospitalizations and ER visits than patients treated with unfixed combinations. In another study, Sicras Mainar et al.Citation20 showed that patients with a fixed-dose combination treatment showed better therapeutic compliance and longer persistence of treatment, a higher rate of optimal control of BP, and a lower cumulative incidence of cerebrovascular accidents with lower total healthcare costs. Improved management of hypertension through better medication compliance and persistence has the potential to produce better health outcomes and significantly reduce costs of a disease that generates a significant economic burden (€24,127 million per year)Citation4 in Germany.

Our analysis has limitations that need to be mentioned. First, we measured compliance and persistence indirectly based on prescription information, which means that true extent of treatment duration or dosing frequency could be under- or over-estimated. Secondly, a substantial percentage (about two thirds) out of 69,060 patients was not included in the analyses of persistence, because there was no 12-month follow-up data on ARBs mono- or combination treatment with AML and/or HCT. Thirdly, we assumed that data in our database were missing at random, thus no missing data imputation was performed. And, finally, multivariate analyses of compliance were adjusted for age, sex, insurance status, and co-morbidities; other potential confounding factors were not taken into account. Despite mentioned limitations, our data provides important information regarding real-life treatment patterns, compliance, persistence, and medication costs in patients with hypertension in Germany.

Conclusions

The study shows considerable variations in ARB treatment patterns among patients, with the majority of patients treated with fixed-dose or semi-fixed combination therapy pointing to a high relevance of combination therapy in real-life treatment in Germany. These variations, also reflected in differing daily anti-hypertensive medication costs, are vital data for the statutory healthcare funds for formulary and reimbursement decisions or as a basis for budget impact models for patients with hypertension. Fixed-dose combinations of ARBs with HCT and/or AML seem to result in better compliance and persistence compared to unfixed regimes of these drug classes, leading to reduction in all-cause hospitalizations, emphasizing the benefit and potential cost-savings of using fixed-dose regimes in a real-life general practice setting in Germany. More research is warranted to investigate the impact of age, gender, diabetes, and other factors driving treatment decisions and, subsequently, influencing utilization and daily costs of anti-hypertensive medications.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The study was financially supported by Daiichi Sankyo Europe GmbH.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Professor Dr Roland Schmieder served as advisor for Daiichi Sankyo Europe GmbH. Andre Oberdiek and Anna Sandberg are employees of Daiichi Sankyo Europe GmbH. For other authors there are no relationships to be declared.

Acknowledgments

No assistance in the preparation of this article is to be declared.

References

- World Health Organization. Prevention of cardiovascular disease: guideline for assessment and management of cardiovascular risk. 2007. Available at http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/guidelines/Full%20text.pdf [Last accessed on November 2nd, 2011]

- Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Kramer H, et al. Hypertension treatment and control in five European countries, Canada, and the United States. Hypertension 2004;43:10-17

- Prugger C, Heuschmann PU, Keil U. Epidemiologie der hypertonie in Deutschland und weltweit. Herz 2006;31:287-93

- Wille E, Scholze J, Alegria E, et al. Modelling the costs of care of hypertension in patients with metabolic syndrome and its consequences, in Germany, Spain and Italy. Eur J Health Econ 2011;12:205-18

- Dickinson HO, Mason JM, Nicolson DJ, et al. Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens 2006;24:215-33

- Mancia G, Laurent S, Agabiti-Rosei E, et al. Reappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: a European Society of Hypertension Task Force document. Blood Press 2009;18:308-47

- Calhoun DA, Lacourciere Y, Chiang YT, et al. Triple antihypertensive therapy with amlodipine, valsartan, and hydrochlorothiazide: a randomized clinical trial. Hypertension 2009;54:32-9

- Fox JC, Leight K, Sutradhar SC, et al. The JNC 7 approach compared to conventional treatment in diabetic patients with hypertension: a double-blind trial of initial monotherapy vs. combination therapy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2004;6:437-42

- Jamerson K, Bakris GL, Dahlof B, et al. Exceptional early blood pressure control rates: the ACCOMPLISH trial. Blood Press 2007;16:80-6

- Neutel JM. Fixed combination antihypertensive therapy. In: Oparil S, Weber MA, eds. Hypertension: a companion to Brenner and Rector's the Kidney. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2005. p 522-9

- Neutel JM, Smith DH, Weber MA, et al. Efficacy of combination therapy for systolic blood pressure in patients with severe systolic hypertension: the Systolic Evaluation of Lotrel Efficacy and Comparative Therapies (SELECT) study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2005;7:641-6

- Neutel JM. Prescribing patterns in hypertension: the emerging role of fixed-dose combinations for attaining BP goals in hypertensive patients. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2389-401

- Smith TR, Philipp T, Vaisse B, et al. Amlodipine and valsartan combined and as monotherapy in stage 2, elderly, and black hypertensive patients: subgroup analyses of 2 randomized, placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007;9:355-64

- Mancia G, De BG, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 ESH-ESC practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: ESH-ESC task force on the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 2007;25:1751-62

- Deutsche Hochdruckliga e.V. DHL®. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hypertonie und Prävention. Leitlinien zur Behandlung der arteriellen Hypertonie. 2008. Available at http://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/046-001_S2_Behandlung_der_arteriellen_Hypertonie_06-2008_06-2013.pdf [Last accessed November 2, 2011]

- Bangalore S, Kamalakkannan G, Parkar S, et al. Fixed-dose combinations improve medication compliance: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 2007;120:713-9

- Brixner DI, Jackson KC, Sheng X, et al. Assessment of adherence, persistence, and costs among valsartan and hydrochlorothiazide retrospective cohorts in free-and fixed-dose combinations. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2597-607

- Gupta AK, Arshad S, Poulter NR. Compliance, safety, and effectiveness of fixed-dose combinations of antihypertensive agents: a meta-analysis. Hypertension 2010;55:399-407

- Jackson KC, Sheng X, Nelson RE, et al. Adherence with multiple-combination antihypertensive pharmacotherapies in a US managed care database. Clin Ther 2008;30:1558-63

- Sicras Mainar A, Galera Llorca J, Muñoz Ortí G, et al.. Influence of compliance on the incidence of cardiovascular events and health costs when using single-pill fixed-dose combinations for the treatment of hypertension. Med Clin (Barc) 2011;136:183-91

- Yang W, Chang J, Kahler KH, et al. Evaluation of compliance and health care utilization in patients treated with single pill vs. free combination antihypertensives. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:2065-76

- Zeng F, Patel BV, Andrews L, et al. Adherence and persistence of single-pill ARB/CCB combination therapy compared to multiple-pill ARB/CCB regimens. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:2877-87

- Erkens JA, Panneman MM, Klungel OH, et al. Differences in antihypertensive drug persistence associated with drug class and gender: a PHARMO study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005;14:795-803

- Hasford J, Mimran A, Simons WR. A population-based European cohort study of persistence in newly diagnosed hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens 2002;16:569-75

- Hasford J, Schroder-Bernhardi D, Rottenkolber M, et al. Persistence with antihypertensive treatments: results of a 3-year follow-up cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:1055-61

- Patel BV, Remigio-Baker RA, Mehta D, et al. Effects of initial antihypertensive drug class on patient persistence and compliance in a usual-care setting in the United States. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007;9:692-700

- Bramlage P, Hasford J. Blood pressure reduction, persistence and costs in the evaluation of antihypertensive drug treatment–a review. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2009;8:18

- Hughes D, Cowell W, Koncz T, et al. Methods for integrating medication compliance and persistence in pharmacoeconomic evaluations. Value Health 2007;10:498-509

- Destro M, Cagnoni F, D'Ospina A, et al. New strategies and drugs in the treatment of hypertension: monotherapy or combination? Recent Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov 2010;5:69-81

- Erdine S. Compliance with the treatment of hypertension: the potential of combintation therapy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2010;12:40-6

- Patel BV, Remigio-Baker RA, Thiebaud P, et al. Improved persistence and adherence to diuretic fixed-dose combination therapy compared to diuretic monotherapy. BMC Fam Pract 2008;9:61

- Schmieder RE. The role of fixed-dose combination therapy with drugs that target the renin-angiotensin system in the hypertension paradigm. Clin Exp Hypertens 2010;32:35-42

- Schrader J, Bramlage P, Luders S, et al. BP goal achievement in patients with uncontrolled hypertension: results of the treat-to-target post-marketing survey with irbesartan. Clin Drug Investig 2007;27:783-96

- Becher H, Kostev K, Schroder-Bernhardi D. Validity and representativeness of the "Disease Analyzer" patient database for use in pharmacoepidemiological and pharmacoeconomic studies. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;47:617-26

- Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008;11:44-7

- Steiner JF, Prochazka AV. The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: methods, validity, and applications. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:105-16

- Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2007;297:177-86

- Schmieder RE, Schwertfeger M, Bramlage P. Significance of initial blood pressure and comorbidity for the efficacy of a fixed combination of an angiotensin receptor blocker and hydrochlorothiazide in clinical practice. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2009;5:991-1000

- Bloom BS. Continuation of initial antihypertensive medication after 1 year of therapy. Clin Ther 1998;20:671-81

- Degli EE, Sturani A, Di MM, et al. Long-term persistence with antihypertensive drugs in new patients. J Hum Hypertens 2002;16:439-44

- Elliott WJ, Plauschinat CA, Skrepnek GH, et al. Persistence, adherence, and risk of discontinuation associated with commonly prescribed antihypertensive drug monotherapies. J Am Board Fam Med 2007;20:72-80

- Hoer A, Gothe H, Khan ZM, et al. Persistence and adherence with antihypertensive drug therapy in a German sickness fund population. J Hum Hypertens 2007;21:744-6

- Mathes J, Kostev K, Gabriel A, et al. Relation of the first hypertension-associated event with medication, compliance and persistence in naive hypertensive patients after initiating monotherapy. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2010;48:173-83

- Jones DW, Hall JE. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure and evidence from new hypertension trials. Hypertension 2004;43:1-3

- Hess G, Hill J, Lau H, et al. Medication utilization patterns and hypertension-related expenditures among patients who were switched from fixed-dose to free-combination antihypertensive therapy. Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2008;33:652-66

- Maronde RF, Chan LS, Larsen FJ, et al. Underutilization of antihypertensive drugs and associated hospitalization. Med Care 1989;27:1159-66

- Paramore LC, Halpern MT, Lapuerta P, et al. Impact of poorly controlled hypertension on healthcare resource utilization and cost. Am J Manag Care 2001;7:389-98

- Rizzo JA, Simons WR. Variations in compliance among hypertensive patients by drug class: implications for health care costs. Clin Ther 1997;19:1446-57

- Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, et al. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care 2005;43:521-30