Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate breast cancer-associated healthcare cost from the payer perspective for the initial year after diagnoses of invasive breast cancer.

Background:

Breast cancer is the second most common malignancy in American women. While lifetime burden-of-care studies have reported spending between $20,000 and $100,000 per patient, previous studies have not outlined first year cost in managing this disease in recently diagnosed patients.

Methods:

This study was a retrospective, matched cohort study of privately-insured patients. Data were from a large US employers’ health claims database (January 2003–September 2008). Breast cancer cases were identified by ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes on index and confirmatory claims. A control group was identified with a ratio of 3:1, matched by demographic and health plan characteristics. Comorbidities were analyzed using the Charlson comorbidity index and AHRQ Comorbidity Software. A multivariate, log-linked, generalized linear model evaluated cost contributions of breast cancer in relation to demographic factors, comorbidities, and plan type.

Results:

The study included 35,057 cases and 105,171 matched controls (mean age 52 years). Common comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes, hypothyroidism, chronic pulmonary disease, and deficiency anemia. In the generalized linear model, the adjusted difference in total healthcare cost was $42,401 per patient within a year, with outpatient services responsible for most of this sum. Breast cancer-associated incremental annual costs per patient in inpatient, outpatient, and prescription categories were $5100, $37,231, and $1037, respectively.

Limitations:

These results may not be representative of the entire US, as data were derived from breast cancer patients with private, employer-based health insurance, and lacked covariates including race/ethnicity, education, income, and disease stage.

Conclusions:

Recently diagnosed breast cancer represents a substantial economic burden for US healthcare payers.

Introduction

American women have a one-in-eight lifetime risk of developing breast cancerCitation1. In 2010, there was an estimated 209,060 new US cases of invasive breast cancer, and 40,230 deathsCitation2. This incidence makes breast cancer the most common cancer among American women aside from skin cancerCitation2. Worldwide, breast cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related deaths among women, with 500,000 deaths in 2005Citation3. Developed regions have almost 3-times the incidence of breast cancer than less-developed regions; however, women from low-income regions tend to have a lower cancer survival rateCitation3.

Early detection, as well as improved treatment, has lead to a drop in US breast cancer mortality. Importantly, mortality has decreased by 3.2% a year in women under 50 years of age, and by 2% in women older than 50 yearsCitation2. Despite the trend toward earlier detection, US patients still receive breast cancer diagnoses after the disease has spread from its initial local siteCitation1. Treatment costs, therefore, can be expected to remain high or increase further, partly also due to innovations in therapy and longer survival.

There are several studies, using a variety of methods, that have documented the economic burden associated with breast cancer in the US population. A 2009 literature review reported that estimates of breast cancer’s lifetime burden ranged from $20,000–$100,000 per patientCitation4. The review found that the large variations in study methods rendered overall cost-of-illness conclusions unreliableCitation4. Many studies used physician billing, which does not accurately reflect the reimbursements doctors received. Physician billing also does not take into account patient or employer costs incurred due to breast cancer, although a few studies did include these perspectives. Other variations in these studies included a large range of ages, follow-up times, and disease-stage distributions. These last two factors—follow-up times and disease stage—are critical when considering lifetime costs, since costs vary by treatment phase (initial, continuing, and terminal). Yet, the annual total cost despite disease stage or treatment phase can be important from the payer perspective.

Few studies have endeavored to calculate the actual costs attributable to breast cancer as relatable to a payer rather than a clinician. Calculating the incremental costs requires selecting a control group similar to the breast cancer population and constructing a multivariate model to adjust for comorbid conditions and demographic factors. Barron et al.Citation5 reported a recent study to conduct such an investigation. It was based on 2004 data and included both newly-diagnosed and pre-existing breast cancer cases in a managed care population. We attempt here to provide breast cancer-attributable costs using newer, more complete data that allow for a specific focus on recently-diagnosed patients (no previous diagnoses for at least last 6 months), broken down by care categories, including inpatient care, outpatient care, and prescription medications.

Patients and methods

Study design

This study was a retrospective, matched cohort study. The study’s main end-point was the incremental difference between the direct healthcare cost from the payer perspective of women in their first year after breast cancer diagnosis compared with similar women without breast cancer in the same year.

The data were extracted from almost 6 years of the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database, encompassing the time period between January 1, 2003 and September 30, 2008. In 2006, MarketScan data covered almost 18 million employees, dependents, and retirees with private healthcare coverageCitation6. MarketScan integrates pharmacy claims along with those for healthcare services. The records include demographics (age, gender, geographic location, and employment type); insurance eligibility (health plan status and coverage with enrollment dates); care episodes (dates, diagnostic codes, and procedure codes for an entire episode); service costs (payments for inpatient and outpatient health services); and outpatient pharmacy claims (drugs supplied along with the payments that plans made for these drugs)Citation6. Patients are tracked through changes in their health plan as long as they stay with the same employerCitation6.

Population

Our study sample consisted of women of 18–64 years of age with recently-diagnosed breast cancer. The index event was a claim containing a primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis code of 174.xx (‘malignant neoplasm of female breast’). Breast cancer was confirmed by at least one additional claim listing a breast cancer ICD-9-CM within 90 days of the index diagnosis in order to ensure that the first breast cancer diagnosis code represented the actual disease condition instead of that for a regular screening.

The non-breast cancer control cohort was matched to index date (month, year), age (within 5 years), gender, geographic region, type of employer, and type of health insurance (fee-for-service or capitated) by exact matching. The index date for non-cancer patients was a random date (within the same month and year) matched with that of a breast cancer patient. The control-to-case matching ratio was 3:1.

Both cases and matched controls had at least 6 months of continuous health plan enrollment before the index date and 12 or more months of continous enrollment after that date. Patients were excluded if their records contained a claim listing a breast cancer diagnostic code less than 6 months prior to the index date. The length of follow-up for this study was 12 months after the index date. Due to its nature as a retrospective database study and deidentified patient data, this study was exempt from IRB approval.

Outcome measures

The main outcome of interest was direct total healthcare cost. The analysis broke down total cost into costs for inpatient care, outpatient care, and medications. The cost estimates were constructed from insurer and health plan reimbursements plus co-payments and deductibles borne by patients. These were adjusted to 2008 US dollars based on the Consumer Price Index’s medical care componentCitation7. Expenses were summarized for each patient and averaged over the study population. The adjusted difference in costs between the women with breast cancer and matched controls defined the incremental costs associated with breast cancer.

A number of covariates were built into a multivariate model in order to ensure a better control for confounding by unmatched covariates in the case and control groups. The covariates consisted of age, geographic region, and rural/urban residence at the index date, type of health plan, relationship to employee plan holder, natural logarithm of total direct healthcare cost for the 6 months prior to the index date, and baseline comorbidities. Region of residence was classified as Northeast, North-central, West, and South. Health plans were classified as health maintenance organization (HMO), point of service (POS), capitated POS, preferred provider organization (PPO), exclusive provider organization (EPO), consumer-driven health plan (CDHP), and comprehensive.

Controlling for comorbidities involved two scoring methods for each subject. The first was the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)Citation8. For this study, the CCI was derived from ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes on all claims for the 6-month baseline period. The second comorbidity rating was an index generated by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Comorbidity Software, version 3.4 Citation9, which utilizes Elixhauser coding algorithmsCitation9,Citation10. This method calculates a list of 30 comorbid conditions contained in the administrative data. The use of both the CCI and AHRQ comorbidity software minimizes confounding due to comorbidities.

Statistical analysis

Cost data are typically right-skewed because of the relatively small number of high-cost subjects. When estimating the marginal cost difference using regression models, the estimate could be unbiased yet unstable given the skewness and kurtosis (‘peakedness’) of the data distribution. It could also be inefficient due to changes in variance as costs increase (heteroscedasticity). Such problems can be mitigated through logarithmic or other transformation of the cost dataCitation11. However, log transformation introduces additional problems when re-transforming back to the dollar value; notably, because log transformation involves geometric—not arithmetic—means and suppresses heteroscedasticityCitation12,Citation13. To avoid these problems, the present study used a generalized linear model (GLM) with a log-link function to identify the disease-attributable healthcare costs after controlling for covariatesCitation13. The variance function of the GLM was determined using the modified Park test reflecting the appropriate cost mean-variance relationship for the current dataCitation14,Citation15. The incremental cost differences in the GLM were estimated using the method of recycled predictionsCitation16. The model’s controlled variables were held at their actual values for each subject. The incremental cost was then estimated by changing only the case/control value. These costs were then averaged over the whole sample population to provide the mean incremental cost results. We chose the GLM over other models that might fit the distribution slightly better because we believe the results of GLM would be easier to interpret to provide a more straightforward meaning.

Results

The study selected 35,057 cases and 105,171 matched controls, with a mean age of 52 years (). The matching of cases and controls ensured similar baseline geographic regions and health plan status. Notably, comorbidities were significantly higher (p < 0.0001) in the cases than the controls. The most common comorbidities were hypertension, diabetes, hypothyroidism, chronic pulmonary disease, and deficiency anemia.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population.

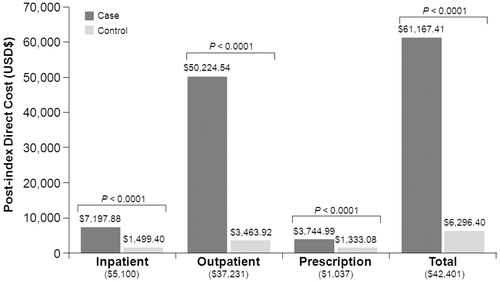

Baseline total per patient healthcare cost in breast cancer cases was almost 3-times that of the controls ($4669 vs $1630; p < 0.0001), and this difference was more driven by outpatient cost. In comparison, cases had nearly 10-fold higher unadjusted total per patient healthcare cost for the first 12 months after the index event ($61,167 vs $6296; p < 0.0001), again driven largely by outpatient cost.

shows the GLM results for the impact of covariates on total healthcare cost. By a larger beta-coefficient, the influence of a breast cancer diagnosis greatly outweighed that of demographic factors, health plan type, and comorbidities.

Table 2. Generalized linear model for direct healthcare cost.

Based on the GLM results, the adjusted difference in total per patient healthcare cost between recently-diagnosed breast cancer patients and their controls was $42,401 (). The breast cancer-associated increases in inpatient, outpatient, and prescription costs were $5100; $37,231; and $1037, respectively, based on their own regression results. The adjusted percent of the total breast cancer-associated costs represented by the incremental inpatient, outpatient, and prescription costs was, respectively, 12%, 86%, and 2%.

Figure 1. Direct healthcare costs associated with breast cancer. Bar charts indicate the unadjusted results. Numbers in parentheses are incremental difference after controlling for age, geographic region, rural/urban habitat, type of health plan, relationship to worker, natural logarithm of pre-index total direct cost, Charlson comorbidity index, and comorbidity software disease categories.

Discussion

In this study of recently-diagnosed breast cancer patients and a matched control population, we identified that the breast cancer diagnosis was a strong determinant of healthcare cost, and moreso than comorbidities or any of the demographic covariates investigated. We looked at a retrospective claims database (MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters), identifying records of any patients of 18 years of age and older with ≥2 breast cancer diagnoses on different dates within 90 days. The predicted first-year mean incremental healthcare cost for breast cancer was $42,401, dominated by payments for outpatient services. Outpatient services in the first year after breast cancer diagnoses usually include lumpectomy, radiation therapy, and neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapies, which may involve trastuzumabCitation17. In contrast, the incremental outpatient pharmacy prescription cost for the first-year was relatively small ($1037).

The difference in results between the present study and previous cost-of-illness studies reveal the crucial role played by the variations in study methods. Barron et al.Citation5 was the study most similar to the present one. It used a health plan claims database and found that, in 2004, the annual mean breast cancer-attributable costs were $12,828 higher than matched controlsCitation5. After adjusting for comorbid conditions, however, their GLM revealed an annual difference of $30,276. Breast cancer patients had 2.28-fold higher (p < 0.0001) direct monthly healthcare costs than non-breast cancer patients, with a projected average of $35,568 vs $7980 per year compared with the control groupCitation5. Although this finding is higher than the costs reported by several earlier studiesCitation18,Citation19, it is lower than that of the present study. There are a number of potential factors that may explain this difference. First, the present study used data from more recent years. It thus incorporates further medical inflation as well as the increasing use of more recent and expensive breast cancer therapies. Second, some of the patients in Barron et al.Citation5 may have had less than 12 months’ follow-up due to changes in their health plan enrollment. Third, the present study included only patients with invasive breast cancer, but Barron et al.Citation5 also followed patients with earlier, less costly disease—in situ or unclassifiable carcinomas (ICD9-CM codes 233.0x, 238.3x, 239.3x). In addition, some of the patients in Barron et al.Citation5 were on continuation or terminal therapy, which likely incur lower costs than patients on initial therapyCitation18,Citation19. It is difficult to conclude how much less-advanced patients or later therapy contributed to the Barron et al.Citation5 findings though because such information was not provided in their paper. Also, comorbidities could have had a greater impact in the Barron et al.Citation5 study than in the present one because their prevalence was greater in the former. Possibly as a result of the greater prevalence of comorbidities, the unadjusted mean total cost in the Barron et al.’sCitation5 control group were higher (when their cost-per-month data were pro-rated over 12 months) than in the current study ($40,224 vs $6296 over 1 year). However, the reverse was true for the breast cancer group, whose cost was lower, but closer to the present study’s finding ($53,052 vs $61,167, respectively)Citation5.

Warren et al.Citation20 reported a mean per-patient increase in Medicare payments from 1991 to 2002 by $4189–$20,929, much lower than in our study. However, these cost calculations do not take into consideration recent-year increases in medical costs, changes in treatment, or increasing survivalCitation20.

As an illustration of how treatment and disease status affect costs, Lamerato et al.Citation21 compared expenditures for primary and recurrent breast cancer in a community care network. For patients with stage I–II breast cancer and subsequent recurrence, mean costs were $38,165 for initial care (first 6 months) and $2564/quarter for continuing care. After the recurrence, they were $47,581 for the first 6 months and then $4934/quarter for post-recurrence continuing care. Terminal care in the last 6 months of life averaged $63,434; stage I–II patients without recurrence averaged $41,345 for the initial 6 months’ care and $1228/quarter for continuing careCitation21. A non-breast cancer control population was not included, so the breast cancer-associated incremental costs could not be estimated.

In another significant cost-of-illness study, Rao et al.Citation19 assessed incremental costs in a Medicare claims database (with 1997 as the year of diagnosis) for metastatic breast cancer patients until death. The mean total costs over an average of 16.2 months’ follow-up were $35,164 for cases and $2167 for controlsCitation19. In addition, the inpatient costs in Rao et al.Citation19 provided the bulk of the incremental cost. Although inpatient hospital costs were considerably lower during the continuation period than during the initial or terminal periods, Medicare costs for home health aid or caregiving were high for metastatic breast cancer patientsCitation19. Interestingly, the overall Medicare costs for patients that were on average 20 years older than in the present study appeared significantly less than the younger patients (i.e. those approaching the age range included in the present study population)Citation19. However, there are a number of reasons why the absolute cost values in Rao et al.Citation19 may not be compared with those observed in the present study. The study period (1997–1999) was considerably earlier than the current one, and the patients were selected to have only very advanced disease. In addition, Medicare’s cost structure differs from that of the private plans enrolling the present study population. Furthermore, Medicare records during the study period for Rao et al.Citation19 did not include outpatient pharmacy expenditures.

The present study, therefore, has several advantages over previous ones. It directly compared costs between breast cancer cases and a matched control group, allowing a determination of disease-attributable cost. It also presented first-year cost rather than lifetime cost. Annual costs are important for comparing breast cancer economic burden to that of other diseases. In contrast, lifetime costs support comparisons between different breast cancer treatment protocols. They also indicate classes of patients needing improved therapeutic interventions. Additionally, the present study population could have more patients with longer follow-up data than others because MarketScan data collect patient records as long as they stay with an employer, regardless of switches in health plans.

A limitation of the study is that it included only women with private employer-based health insurance. There were no women in the study with individual health plans, government employee insurance, non-supplemental Medicare, or Medicaid, so the present sample was not representative of the entire US breast cancer population. Second, important covariates were missing from the MarketScan data. These include race/ethnicity, education, income, and stage of disease. Such uncontrolled covariates may have confounded the findings reported here. In particular, there is considerable variation in breast cancer stage among recently diagnosed patients, and this difference may affect costs. Future research is needed to understand the impact of disease stage on cost in recently diagnosed patients. Third, the 6-month baseline period may not be long enough to ensure that patients are truly newly diagnosed. Due to the nature of the disease, however, most patients with pre-existing breast cancer would have presented a breast cancer-related claim during the 6 months before the index date. Finally, future research is needed to examine the detailed health utilization after the index diagnosis; for example, the utilization components of the identified expensive outpatient cost.

Conclusions

Results of our study show that the first-year incremental healthcare cost associated with breast cancer diagnoses are roughly $40,000 per patient, with most of the added cost incurred in outpatient settings. This study was conducted within a privately-insured population. Generalization of the findings should take precautions also because of the lack of information on breast cancer stage and sub-type. Further expansion of this study population and a better knowledge of its characteristics would refine the present findings and make them more applicable to the general US population.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by Sanofi-Aventis U.S. Both authors participated in the study design, data collection, interpretation, and writing of the manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

A.Z.F. received sponsorship from Sanofi-Aventis; M.J. is an employee of Sanofi-Aventis U.S.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by David Pechar, PhD, at Phase Five Communications Inc. and funded by Sanofi-Aventis U.S.

This study was previously presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in Chicago, IL, June 4–8, 2010.

References

- National Cancer Institute. SEER stat fact sheets: breast. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed November 9, 2010

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2010. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-026238.pdf. Accessed November 6, 2010

- Ribeiro PS, Jacobsen KH, Mathers CD, et al. Priorities for women's health from the Global Burden of Disease study. Intl J Gynecol Obstet 2008;102:82-90

- Campbell JD, Ramsey SD. The costs of treating breast cancer in the US: a synthesis of published evidence. Pharmacoeconomics 2009;27:199-209

- Barron JJ, Quimbo R, Nikam PT, et al. Assessing the economic burden of breast cancer in a US managed care population. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;109:367-77

- Adamson DM, Chang S, Hansen LG. Health research data for the real world: The MarketScan Databases. Thompson Scientific, Thomson Reuters, Ann Arbor, MI; 2008

- Chained Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers (C-CPI-U) 1999-2010, Medical Care. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010. http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?su. Accessed November 28, 2010

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-83

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project: Comorbidity Software. Version 3.4. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8-27

- Box GEP, Cox DR. An analysis of transformation. J R Stat Soc B 1964;26:211-52

- Duan N. Smearing estimate: a nonparametric retransformation method. J Am Stat Assoc 1983;78:605-10

- Manning WG. The logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and the retransformation problem. J Health Econ 1998;17:283-95

- Park RE. Estimation with heteroskedastic error terms. Econometrica 1966;34:888

- Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ 2001;20:461-94

- Fu AZ, Kattan MW. Racial and ethnic differences in preference-based health status measure. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:2439-48

- Maughan KL, Lutterbie MA, Ham PS. Treatment of breast cancer. Am Fam Physician 2010;81:1339-46

- Fireman BH, Quesenberry CP, Somkin CP, et al. Cost of care for cancer in a health maintenance organization. Health Care Financ Rev 1997;18:51-76

- Rao S, Kubisiak J, Gilden D. Cost of illness associated with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2004;83:25-32

- Warren JL, Yabroff KR, Meekins A, et al. Evaluation of trends in the cost of initial cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:888-97

- Lamerato L, Havstad S, Gandhi S, et al. Economic burden associated with breast cancer recurrence: findings from a retrospective analysis of health system data. Cancer 2006;106:1875-82