Abstract

Objective:

To assess the costs of oral treatment with Gilenya® (fingolimod) compared to intravenous infusion of Tysabri® (natalizumab) in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) in The Netherlands.

Methods:

A cost-minimization analysis was used to compare both treatments. The following cost categories were distinguished: drug acquisition costs, administration costs, and monitoring costs. Costs were discounted at 4%, and incremental model results were presented over a 1, 2, 5, and 10 year time horizon. The robustness of the results was determined by means of a number of deterministic univariate sensitivity analyses. Additionally, a break-even analysis was carried out to determine at which natalizumab infusion costs a cost-neutral outcome would be obtained.

Results:

Comparing fingolimod to natalizumab, the model predicted discounted incremental costs of −€2966 (95% CI: −€4209; −€1801), −€6240 (95% CI: −€8800; −€3879), −€15,328 (95% CI: −€21,539; −€9692), and −€28,287 (95% CI: −€39,661; −€17,955) over a 1, 2, 5, and 10-year time horizon, respectively. These predictions were most sensitive to changes in the costs of natalizumab infusion. Changing these costs of €255 within a range from €165–364 per infusion resulted in cost savings varying from €4031 to €8923 after 2 years. The additional break-even analysis showed that infusion costs—including aseptic preparation of the natalizumab solution—needed to be as low as the respective costs of €94 and €80 to obtain a cost neutral result after 2 and 10 years.

Limitations:

Neither treatment discontinuation and subsequent re-initiation nor patient compliance were taken into account. As a consequence of the applied cost-minimization technique, only direct medical costs were included.

Conclusion:

The present analysis showed that treatment with fingolimod resulted in considerable cost savings compared to natalizumab: starting at €2966 in the first year, increasing to a total of €28,287 after 10 years per RRMS patient in the Netherlands.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, autoimmune, and inflammatory neurodegenerative condition that affects the central nervous system (CNS); causing demyelination and axonal loss, leading to neurological ‘attacks’ or relapses. Disease progression is marked by neurologic impairment, which is commonly rated with the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS); a score ranging from 0, reflecting a normal neurological exam, to 10, reflecting death due to MSCitation1. In the Netherlands, there were ∼ 16,200 MS patients in December 2007, and prevalence shows an increasing trendCitation2. Women are more often affected than men (2.5:1), and age at onset is typically 20–40 yearsCitation3. MS, therefore, has a large impact on the young adult population; affecting a period of life that is key for career development and family planning.

The economic burden of multiple sclerosis in The Netherlands has been well-described by Kobelt et al.Citation3,Citation4. According to this study, direct costs including informal care were €9676/patient-year for MS patients with an EDSS of 2.0, and €23,093/patient-year for those with an EDSS of 6.5 (cost year 2005). Inclusion of productivity losses would approximately double these costs (human capital method)Citation3.

The focus of this study is relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), which is the most common form of MS. Approximately 70% of patients with MS experience a relapsing–remitting course initiallyCitation5; of which ∼ 80% progress to secondary progressive MS after a median of 10–12 yearsCitation5,Citation6. RRMS is characterized by repeated relapses during which nervous system symptoms flare up; usually followed by gradual–complete or partial–recovery.

To date, first line disease-modifying therapy (DMT) for RRMS is provided in the form of interferon-β preparations or glatiramer acetateCitation7. Novel DMTs that have obtained approval in the European Union for the treatment of RRMS are Tysabri® (natalizumab) since 2006 and Gilenya® (fingolimod) since 2011; with fingolimod being the first oral treatment for relapsing MS patients. (Tysabri® is a registered trademark of Elan Pharma International Ltd., Athlone, Ireland; Gilenya® is a registered trademark of Novartis Europharm Ltd., Horsham, United Kingdom.) Both drugs have similar indications in EuropeCitation8: second-line therapy in RRMS patients not tolerating or not responding to first-line DMTs, or first-line therapy for highly active RRMS patientsCitation9,Citation10. Efficacy and tolerability of both drugs have been assessed in placebo-controlled trials: fingolimod in the FREEDOMSCitation11 trial, natalizumab in the AFFIRMCitation12 trial; both with a duration of 2 years. In addition, fingolimod was directly compared to Avonex® (interferon-β-1a) in the 1-year head-to-head TRANSFORMSCitation13 trial. (Avonex® is a registered trademark of Biogen Idec Ltd., Maidenhead, United Kingdom.) Common end-points in these trials were the annualized relapse rate (ARR); the rate of sustained progression of disability as measured by the EDSS; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lesion count; and brain atrophy. Both drugs demonstrated superior efficacy compared to placebo on ARR, disability and MRI lesion count; in addition, fingolimod showed benefit on brain atrophy. Compared to interferon-β-1a fingolimod was superior with respect to ARR, MRI lesion count, and atrophy. Natalizumab has not been tested in a direct head-to-head comparison with any approved MS therapy.

To determine the health economic value of fingolimod compared to natalizumab in the optimization of treatment of patients with RRMS, physicians and decision-makers must critically appraise and balance clinical risk-benefit profiles against the economic consequences. The relative therapeutic value was assessed by the European Medicines AgencyCitation8 (EMA), who recommended that the indication of fingolimod should be in line with that for natalizumab; economic consequences were investigated in the current analysis, which was initiated to substantiate the request for reimbursement of fingolimod in The Netherlands.

Typically, when two drugs have comparable efficacy and tolerabilityCitation8, the economic consequences are assessed by means of a cost-minimization analysis. Accordingly, the research objective of the present analysis was to assess the costs of oral treatment with fingolimod compared to intravenous infusion of natalizumab in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis from the perspective of The Netherlands healthcare system.

Methods and materials

Cost-minimization analysis

In light of the available evidence on fingolimod and natalizumab—i.e. the FREEDOMSCitation11 trial, TRANSFORMSCitation13 trial, AFFIRMCitation12 trial, and sub-group analyses based on these trials—the conclusions of the Scientific Advisory Group Neurology (SAG-N) in answer to the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use of the EMA included that (quoteCitation8, February 2011): ‘The efficacy of fingolimod in the treatment of MS could be regarded as broadly similar to that of natalizumab (p. 83)’ and that ‘the difference in the nature and severity of the risk profiles of fingolimod and natalizumab cannot be used to differentiate these two drugs (p. 83)’. For these reasons, the group recommended that ‘the indication (for fingolimod) should be in line with that for natalizumab (p. 83)’. These conclusions were endorsed by the Dutch CFH opinionCitation14, issued on behalf of the Dutch Health Care Insurance Board (CvZ). In both The Netherlands and Sweden, a cost-minimization approach has been accepted by the respective health authoritiesCitation14,Citation15.

Ideally comparability between drugs is based on a head-to-head trial, but such data are not available for the current comparison. Therefore, based on the above conclusions of the SAG-N and the viewpoint of the Dutch (and Swedish) health authorities, the appropriate way to compare fingolimod to natalizumab in The Netherlands is a cost-minimization analysis (CMA). In accordance with the Dutch guidelines for pharmacoeconomic research, only specific direct medical costs inside the healthcare system—i.e. drug costs and drug treatment-related costs—were included in the CMACitation16.

Base case inputs

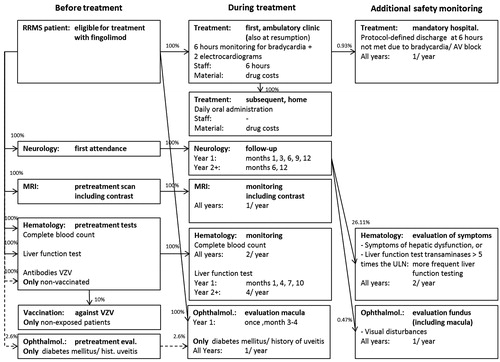

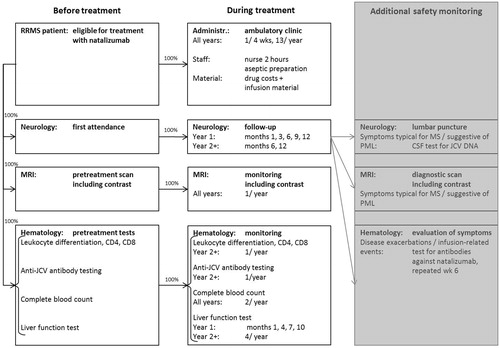

In the CMA, the following treatment-related cost categories were distinguished: (1) drug acquisition costs; (2) administration costs; and (3) monitoring costs; the latter consisting of costs for specialist visits, testing/imaging, and additional safety monitoring. Additional safety monitoring costs, i.e. in the case of adverse events (AEs), were considered drug treatment-related and therefore taken into account for fingolimod (and conservatively discarded for natalizumab). Event costs fall, however, outside the scope of a CMA. Population characteristics and AE incidence were extracted from the TRANSFORMSCitation13 trial (0.5 mg fingolimod/day, n = 429), which reported AE incidence in more detail than the FREEDOMSCitation11 trial; overall, there were no remarkable differences between these two studies. An overview of the cost categories is provided in (fingolimod) and (natalizumab). All unit costs have been updated to 2011 price levels using harmonized consumer price index figuresCitation17. Annual costs were reported on a per-patient basis.

Table 1. Overview of resource use and costs related to drug administration and monitoring of fingolimod (cost year 2011).

Table 2. Overview of resource use and costs related to drug administration and monitoring of natalizumab (cost year 2011).

Drug costs

Drug costs for fingolimod were based on once-daily oral administration of 0.5 mg. Those for natalizumab were based on 4-weekly intravenous infusion of 300 mg; equal to 13 administrations on a yearly basis. In this economic analysis, treatment was assumed to be uninterrupted with ideal compliance. Drug costs (pharmacy purchase price level) were obtained from the Z-indexCitation18. Costs were based on drug prescriptions covering a 90-day treatment period, decreased with the claw-back, increased with a prescription cost of €7.50 (i.e. prescription cost 2011) and VAT was added. No distinction was made between the drug price calculation for intra- and extra-mural drugs following the guideline on costing researchCitation16. Respective annual drug costs for fingolimod and natalizumab amounted to €23,839 and €22,802 per patient.

Administration costs

Once-daily administration of fingolimod is not associated with administration costs as it is an oral drug that patients can take themselves. Because initiation of fingolimod causes a transient—mostly asymptomatic—decrease in heart rate and may be associated with atrioventricular (AV) conduction delays, all patients should be observed for a period of 6 h—i.e. a daycare visitCitation19–21—for signs of bradycardia at treatment (re)initiationCitation9 at a cost of €254.86Citation1Citation6 while taking the first dose.

Four-weekly infusion of natalizumab takes place at the ambulatory care clinic; although some clinics hospitalize patients for one night after the first two administrationsCitation22,Citation23. It was assumed that a daycare visit was charged (same cost of €254.86Citation1Citation6 as above) for each intravenous infusion of natalizumab—i.e. 13 per year—including nurse labor (∼ 2 hCitation10). Infusion material costs were conservatively discarded.

Annual administration costs for fingolimod amounted to €305.04 (including two electrocardiogramsCitation20 at a cost of €25.09Citation24 each) and for natalizumab to €4401.84 (including aseptic preparationCitation25 at a unit cost of €82.82Citation1Citation6) in the first year; and, respectively, to €0.00 and €4401.84 in subsequent years (see and ).

Monitoring costs: Specialist visits

To date, no guidelines have been formulated by the CBO (Dutch Clinical Guidelines) or by the NVN (Dutch Neurology Association) for treatment and monitoring of MS. The frequency of follow-up visits at the neurologist were therefore extracted from British guidelinesCitation26 and applied to both treatments.

Fingolimod treatment is associated with a potential increase in the risk of macular edema. Therefore, all patients treated with fingolimod have an ophthalmology examination 3–4 months after treatment initiationCitation9. In addition, patients with diabetes mellitus or with a history of uveitis require an ophthalmologic assessment prior to initiation as well as monitoring during treatment, because they are at increased riskCitation9. This proportion was estimated at 2.6% (standard error, SE: 0.3%Citation27); consisting of 1.3% diabetes mellitusCitation17 and 1.3% cumulative incidence of uveitisCitation27 until the age of 37 yearsCitation13.

Monitoring costs: Testing/imaging

For both fingolimod and natalizumab, a recent complete blood count (CBC)—including white blood cell count—is required before treatment initiation and periodic assessment is recommendedCitation9,Citation22,Citation26. For fingolimod treatment, recent liver function levels should be available before initiation and should be monitored at 3-monthly intervals in the first year and periodically thereafterCitation9. For patients treated with natalizumab 3-monthly monitoring is prescribed as wellCitation22. Hematologic tests specific for natalizumab treatment are an immune status test (leukocyte differentiation, CD4, CD8Citation23,Citation25) and an anti-JC virus antibody test as part of the treatment preparation phaseCitation10,Citation25 as well as during the monitoring phaseCitation10.

Patients treated with fingolimod without a history of chickenpox or without vaccination against the Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) should be tested for antibodies against VZVCitation9. Because VZV vaccination is not included in the Dutch national immunization scheme, this cost item was applied for all patientsCitation19,Citation21. It can be expected that at maximum 10% of patientsCitation28 would still require vaccination and these costs were included.

Imaging by means of MRI was included for both fingolimod and natalizumab: a recent MRI scan is required before the start of either treatmentCitation10,Citation19,Citation21,Citation25, and this scan should be updated on a yearly routine basisCitation10,Citation22. The disease indications for both drugs refer to ‘Gadolinium-enhancing lesions’Citation9,Citation10, therefore costs for usage of contrast were included.

Monitoring costs: Additional safety monitoring fingolimod

For patients receiving fingolimod treatment, additional costs associated with monitoring of adverse events—as observed during the 1-year TRANSFORMSCitation13 trial—were applied to the first as well as to subsequent years. The following cost items were considered (see ): hospitalization due to bradycardia or AV block, additional liver function testing and additional ophthalmologic evaluation. Hospitalization was defined as not meeting the protocol-defined discharge criteria after 6 h of observation (required at initiation of fingolimod treatment). This occurred in 0.93% (SE: 0.46%) of patientsCitation13. Additional liver function tests are recommended for patients developing abnormal liver function, fatigue or nauseaCitation9. Either one of these symptoms occurred in 26.11% (SE: 2.12%) of patientsCitation13. The annual incidence of macular edema was 0.47% (SE: 0.33%)Citation13. These patients were assumed to undergo an additional ophthalmologic evaluation, including fundus photography.

It is known from the AFFIRMCitation12 trial, as well as post-market-entry dataCitation10,Citation29, that treatment with natalizumab also leads to medical resource consumption associated with monitoring of adverse events; especially as use of natalizumab may result in an increased risk of progressive multi-focal leukoencephalopathy (PML). Suspicion of PML is followed up by CSF analysis and MRI. However, in the current analysis these additional natalizumab safety monitoring costs were conservatively disregarded.

In and the flowcharts of patients, respectively, receiving fingolimod and natalizumab treatment are displayed to provide an overview of which portion of patients are receiving which resource at which point in time. In these figures the timing of resource use was split into ‘before treatment’, ‘during treatment’, and ‘additional safety monitoring’ (in the case of adverse events). In the additional safety monitoring items were shaded, because they were not accounted for in the cost estimation of natalizumab treatment.

Base case analysis

Drug acquisition costs and drug therapy-related costs were cumulated over a 1, 2, 5, and 10 year period. In accordance with the Dutch guidelines for pharmacoeconomic research, costs were discounted at 4%Citation16. The 10-year time horizon was included to show the impact of discounting on the incremental model results within this CMA. Because both placebo-controlled trialsCitation11,Citation12 had a duration of 2 years, costs per category were detailed for a 2-year time horizon.

Sensitivity analyses

The impact of uncertainty on the model results was tested with deterministic univariate sensitivity analyses (varying each parameter using the outer limits of their 95% confidence intervals), a probabilistic multivariate sensitivity analysis, and three scenario analyses. Parameters included in the sensitivity analyses were estimates reflecting the proportion of patients consuming specific medical resources, the frequency of resource use, and unit costs. Drug costs and frequency of administration were not varied as these parameters do not carry uncertainty.

Parameter uncertainty around proportions was reflected by beta distributions. Standard errors were derived from the TRANSFORMSCitation13 trial and De Smet et al.Citation27 Frequency estimates were modeled using triangular distributions; cost estimates using gamma distributions. If standard errors could not be derived from their source references, standard errors were estimated at 20% around each point estimate. Please note that a proportion of 100% was interpreted as obliged, and therefore these parameters were not varied within the sensitivity analyses. The univariate sensitivity analyses were applied to the discounted incremental costs at a 2-year time horizon.

To determine the 95% confidence intervals around the point estimates of incremental costs, a probabilistic multivariate sensitivity analysis (PSA) was performed. Via random selection of each variable from its corresponding distribution, new estimates of proportions, costs, and resource use were obtained; this procedure was repeated 1000 times.

In addition to the above-described sensitivity analyses, three scenario analyses were performed. The first was a break-even scenario; varying the cost estimate for intravenous administration of natalizumab (i.e. €254.86 + €82.82 = €337.68). In this scenario it was determined which cost level of intravenous infusion would lead to a cost-neutral (discounted) outcome after, respectively, 1, 2, 5, and 10 years.

The second scenario analysis concerned the incremental model results in case all parameters that carry uncertainty would be set at their—for fingolimod—worst case values of their 95% CIs. In the last scenario the opposite case was analyzed, i.e. the best case scenario for fingolimod.

Results

Base case analysis

Total costs estimated in the first year differed from those in year 2 and beyond because of two reasons: (1) certain tests are recommended before treatment initiation and these are included in the first year; and (2) monitoring—i.e. specialist visits and testing/imaging—is more frequent during the first year. The discounted base case outcomes of the CMA, cumulated over a 1, 2, 5, and 10 year time horizon, are displayed in . The predicted discounted incremental costs for fingolimod were lower than those for natalizumab; starting in the first year at cost savings of €2966; increasing to savings of €28,287 after 10 years.

Table 3. Total discounted costs and incremental analyses including predicted 95% confidence intervals (CIs) after 1, 2, 5, and 10 patient years of treatment, respectively.

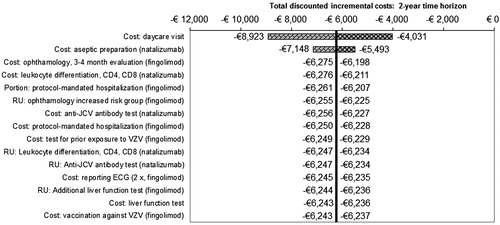

To provide insight into the influence of different cost categories, displays the discounted costs per cost category cumulated over a 2-year time horizon. It shows that the two main drivers of the current outcomes of the CMA were drug costs and administration costs. Drug acquisition costs were higher for fingolimod than for natalizumab. The incremental discounted drug costs increased over time; estimated at €2033 after 2 years, and at €8742 after 10 years. However, these incremental costs were completely offset by cost savings due to lower administration costs for fingolimod than for natalizumab. These savings increased over time and were estimated at €8329 after 2 years, and at €36,826 after a 10 year time horizon. The same table () also shows that the economic impact of additional safety monitoring (€38 after 2 years for fingolimod; not included for natalizumab) is only marginal.

Table 4. Discounted cost estimates per cost category over a 2-year time horizon.

Sensitivity analyses

The probabilistic sensitivity analysis was conducted in order to estimate 95% confidence intervals around the discounted incremental costs after, respectively, 1, 2, 5, and 10 years. These results are displayed in and show that fingolimod’s predicted cost savings can be labeled as statistically significant at all time points; as the 95% confidence intervals around the incremental costs do not contain zero.

The results of the deterministic univariate sensitivity analyses are displayed in the tornado graph in . The cost estimate for a daycare visit was found to be the most important parameter. This cost item (€254.86) was both applied to the first administration of fingolimod, as well as each 4-weekly administration of natalizumab. Changing this parameter within the outer limits of its 95% CI—i.e. from €164.93 to €364.04—resulted in incremental costs ranging from −€4031 to −€8923. The second-most influential parameter, linked to each administration of natalizumab, was found to be the cost of aseptic preparation. This parameter was varied from €53.59 to €118.30.

Figure 3. Overview of the 2-year results of the conducted deterministic univariate sensitivity analyses of fingolimod vs natalizumab. The bars in the tornado graph represent the impact on incremental costs when varying each parameter between the outer limits of their 95% CIs. The costs for a daycare visit both represent the costs of the first administration of fingolimod and the costs of each administration of natalizumab. Only the 15 most influential parameters are displayed.

The cost associated with intravenous infusion of natalizumab—consisting of the cost of a daycare visit plus the cost of aseptic preparation of the natalizumab solution—is the key driver in the CMA (see ). In the break-even scenario these combined costs were varied to determine at which level treatment with natalizumab would cost the same as fingolimod. Assessed for the time horizons of 1, 2, 5, and 10 years, the respective break-even drug administration costs for natalizumab were estimated at €110, €94, €84, and €80. This implies that, even over a 1-year period, these costs per natalizumab infusion, i.e. €337.68, would need to be reduced by a factor of ∼ 3 to break even; which, however, seems unrealistic in clinical practice.

Results of the worst case and best case scenarios are presented in for time horizons of 1, 2, 5, and 10 years. These results show that, even in the worst case scenario, fingolimod remains cost saving (all time horizons).

Table 5. Discounted incremental costs after 1, 2, 5, and 10 years: base case, worst case, and best case scenario.

Discussion

The objective of the presented cost-minimization analysis was to assess the costs of oral treatment with fingolimod compared to intravenous infusion of natalizumab in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis in The Netherlands. Treatment with fingolimod was estimated to result in statistically significant cost savings compared to treatment with natalizumab; starting in the first year at €2966 (95% CI: €1801; €4209), and increasing to total savings of €28,287 (95% CI: €17,955; €39,661) after 10 years of continuous treatment, assuming 100% compliance. Key influential parameters that were identified in the sensitivity analyses were the cost of a daycare visit and the cost of aseptic preparation of the natalizumab solution. Both these costs apply to each administration of natalizumab—i.e. 13 per year—whereas the costs of a daycare visit only apply to the first administration of fingolimod. The considerable cost savings due to reduced drug administration costs when treating patients with fingolimod completely offset its higher drug costs. Administration costs of natalizumab would need to be reduced as much as a factor of 3 in order to obtain a cost neutral result; this, however, seems an unlikely scenario. The other conducted sensitivity analyses also confirmed the robustness of the total estimated cost savings.

The rationale for a cost-minimization approach was substantiated by the recommendation of the scientific advisory group of the EMACitation8—and endorsed by the Dutch CFH opinionCitation14—namely, that based on the currently available evidence fingolimod and natalizumab, should have the same indication because of similar efficacy and safety. Ideally, the substantiation of a cost-minimization analysis would result from a head-to-head clinical trial showing similar efficacy and tolerability. However, such data are not available for the current comparison. When comparing our analytical technique and results with other published evidence, the outcome of a recent network meta-analysis by Del Santo et al.Citation30 concerning treatment with interferon beta-1a/1b, glatiramer, fingolimod, and natalizumab was in line with the EMA conclusions as no significant difference in efficacy was found between fingolimod and natalizumab. It should be noted though that in the referred study the efficacy end-point was the relapse-free portion at 12 months instead of the ARR.

The authors do acknowledge that, in spite of the above EMA recommendationCitation8, treating physicians may wish to compare fingolimod and natalizumab in terms of their annualized relapse rates (ARR). However, an indirect comparison between fingolimod and natalizumab via their respective placebo-controlled trials is hampered because of differing definitions of relapse and differing patient characteristics. For instance, the mean pre-randomization disease duration was longer for patients participating in the FREEDOMS trial than for those in the AFFIRM trial: 8.1 yearsCitation11 vs 5.2 yearsCitation31, respectively. Related to that, 57% of the FREEDOMS participants were treatment-naïveCitation11, as opposed to ∼ 92% of the AFFIRM participantsCitation32. The latter is an important difference as the ARR reduction over 2 years relative to placebo was 54% in the fingolimod treatment arm as a wholeCitation11; whereas consideration of treatment-naïve patients only—i.e. to approximate the AFFIRM population—led to an ARR reduction of 64%Citation33. This ARR reduction is comparable to the one resulting from the AFFIRM trial for natalizumab relative to placebo, i.e. 68%Citation12. Despite the above-addressed differences between the trials, an indirect comparison between fingolimod and natalizumab was performed by O’Day et al.Citation34, using the ARR reductions relative to placebo that were observed in the FREEDOMSCitation11 and AFFIRMCitation12 trials. In this analysis, natalizumab was found to dominate fingolimod. Note that it was performed from the perspective of the US, where fingolimod has a different registration than in Europe. Post-marketing data may provide new insights in the (near) future, but are currently too scarce to reject/reinforce comparability based on the placebo-controlled trials FREEDOMSCitation11 and AFFIRMCitation12. In case future evidence would reveal a well-grounded difference in relapse rate, its impact on an economic evaluation from a Dutch perspective could be considerable, with relapse costs estimated at ∼ €2800 by Kobelt et al.Citation3,Citation4.

The results of this analysis should be interpreted while keeping in mind that certain cost items as well as quality-of-life aspects were not incorporated. First, as a consequence of the underlying assumption of similar efficacy and tolerability, the implications of occurrence and treatment of safety events were not taken into account. Additional safety monitoring costs related to such events were taken into account for fingolimod; whereas for natalizumab these were conservatively discarded. Although definitely of importance for the individual patient, the incidence and associated monitoring of the rare event of progressive multi-focal leukoencephalopathy (PML)—which has been linked to treatment with natalizumabCitation10,Citation29—were not taken into account as the base case time horizon of 2 years was too short to capture the presumed existing dose-duration-dependent increase in the risk of developing PML in patients treated with natalizumabCitation29. Similarly, the rare severe cardiovascular events observed in patients treated with fingolimod were not taken into account; in this case because the data reviewed by the EMA were not conclusive as to whether fingolimod is linked to these eventsCitation35. Secondly, as a consequence of the applied cost-minimization technique, only direct medical costs were included. However, the difference in administration routes, i.e. oral for fingolimod (home) and intravenous infusion for natalizumab (clinic), is expected to result in substantial (in)direct non-medical cost savings for fingolimod in terms of lower travel expenses and less days lost from work. Thirdly, possible patient preferences for either administration route were not part of the performed CMA but could play a role; potentially affecting quality-of-life and adherence. On one hand, patients with injection anxiety may demonstrate improved compliance if treated with fingolimod instead of natalizumab. On the other hand, patients may feel more obliged to keep a hospital appointment for a natalizumab infusion than to take fingolimod themselves.

The main strengths of the current study are that: the applied methodology to assess the relative costs of treating patients with fingolimod vs natalizumab is straightforward, yet well-substantiated by means of published evidence; moreover, the results are based on a detailed analysis of relevant cost items, using clinical guidelines, drug-specific summary of product characteristics, risk management plans, and Dutch hospital protocols as our main sources of input for estimation of medical resource consumptionCitation9,Citation10,Citation19–23,Citation25,Citation26. A limitation of our study is the assumption that patients are treated continuously; treatment discontinuation and subsequent re-initiation were not taken into account, as there are no long-term real world data yet available on general treatment patterns—including compliance—of patients treated with either fingolimod or natalizumab.

Conclusion

The opinion of the scientific advisory group of the EMA and the fact that the registered indications for fingolimod and natalizumab are equal in the European Union formed the basis for the cost-minimization approach undertaken in this study. Under the condition of similar efficacy and tolerability, the presented analyses showed that treatment with fingolimod was estimated to result in substantial—as well as robust—costs savings compared to treatment with natalizumab in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis in The Netherlands.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This manuscript was funded by Novartis Pharma B.V., Arnhem, The Netherlands.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MTG and WSH are employed by Novartis Pharma B.V. MH, MJT, and BGV are employed by Pharmerit B.V., a consulting company which provides services to Novartis Pharma B.V., amongst others. STFMF has been a paid consultant for Novartis, Biogen Idec, and Merck Serono in the past.

CMRO peer reviewers may have received honoraria for their review work. The peer reviewers on this manuscript have disclosed that they have no relevant financial relationships.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (97.4 KB)References

- Kurtzke J. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983;33:1444-52

- Nationaal Kompas Volksgezondheid RIVM. Cijfers multiple sclerose (prevalentie, incidentie en sterfte naar leeftijd en geslacht). 2010. www.nationaalkompas.nl. Accessed June 22, 2012

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, et al. Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis in The Netherlands. HEPAC: health economics in prevention and care. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7(2 Suppl):S55-64

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, et al. Costs and quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis in Europe. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:918-26

- Weinshenker B. The natural history of multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin 1995;13:119-46

- Naci H, Fleurence R, Birt J, et al. The impact of increasing neurological disability of multiple sclerosis on health utilities: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Econ 2010;13:78-89

- College voor Zorgverzekeringen. Farmacotherapeutisch Kompas. 2011. www.fk.cvz.nl. Accessed June 22, 2012

- European Medicines Agency. Assessment report: Gilenya (EMEA/H/C/2202). European Medicines Agency, London, UK; 2011. p 1–117

- Novartis Europharm Limited. Summary of product characteristics Gilenya. Novartis Europharm Limited, Horsham, UK; 2011. p 1–17

- Elan Pharma International Ltd. Summary of product characteristics Tysabri. Elan Pharma International Ltd., Athlone, Ireland; 2006. p 1–36

- Kappos L, Radue E, O’Connor P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Eng J Med 2010;362:387-401

- Polman C, O’Connor P, Havrdova E, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Eng J Med 2006;354:899-910

- Cohen JA, Barkhof F, Comi G, et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Eng J Med 2010;362:402-15

- College voor Zorgverzekeringen. CFH rapport 12/02: fingolimod (Gilenya). College voor Zorgverzekeringen, Diemen, The Netherlands; 2012, p. 1–6

- TLV Tandvårds- och läkemedelsförmånsverket (Swedish Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency). Swedish TLV report fingolimod (Gilenya) 11/08. TLV, Täby, Sweden; 2011. p 1–4

- College voor Zorgverzekeringen. Handleiding voor kostenonderzoek: methoden en standaard kostprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. 2010

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. CBS Statline. 2011. http://statline.cbs.nl. Accessed June 22, 2012

- Z-Index B.V. Z-Index, Taxe. 2011. http://www.z-index.nl/taxe. Accessed June 22, 2012

- Hospital protocol 2. Hospital protocol: Fingolimod (Gilenya), Anonymous, The Netherlands; 2011. p 1–4

- Hospital protocol 3. Hospital protocol: Fingolimod (Gilenya), Anonymous, The Netherlands; 2011. p 1–3

- Hospital protocol 4. Hospital protocol: Fingolimod (Gilenya), Anonymous, The Netherlands; 2011. p 1–5

- Hospital protocol 5. Hospital protocol: Natalizumab (Tysabri), Anonymous, The Netherlands; 2011. p 1–7

- Hospital protocol 6. Hospital protocol: Natalizumab (Tysabri), Anonymous, The Netherlands; 2011. p 1–3

- Nederlandse Zorgautoriteit. NZa Tariefapplicatie. 2011. http://dbc-tarieven.nza.nl/Nzatarieven. Accessed June 22, 2012

- Hospital protocol 1. Hospital protocol: Natalizumab (Tysabri), Anonymous, The Netherlands; 2006. p 1–7

- Association of British Neurologists. Revised (2009) Association of British Neurologists’ guidelines for prescribing in multiple sclerosis, ABN, London, UK; 2009. p. 1–5

- De Smet MD, Taylor SRJ, Bodaghi B, et al. Understanding uveitis: the impact of research on visual outcomes. Prog Retin Eye Res 2011;30:452-70

- Donker G, van der Haar E. Waterpokken: vaccinatie invoeren of niet? Huisarts en Wetenschap 2009;52:165

- Clifford DB, De Luca A, DeLuca A, et al. Natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with multiple sclerosis: lessons from 28 cases. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:438-46

- Del Santo F, Maratea D, Fadda V, et al. Treatments for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: summarising current information by network meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2012;68(4):441-8. Epub 2011 Nov 5

- Goodman A. Multiple sclerosis: treatment update. 2008:1–10. http://www.ucsfcme.com/2008/MNR08001/GoodmanMultipleSclerosisHighlights.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2012

- Hutchinson M, Kappos L, Calabresi PA, et al. The efficacy of natalizumab in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: subgroup analyses of AFFIRM and SENTINEL. J Neurol 2009;256:405-15

- Von Rosenstiel P, Hohlfeld R, Calabresi P, et al Clinical outcomes in subgroups of patients treated with fingolimod (FTY720) or placebo: 24-month results from FREEDOMS. In: 26th Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. 16. Göteborg, Sweden; 2010, p 434

- O’Day K, Meyer K, Miller RM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of natalizumab versus fingolimod for the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. J Med Econ 2011;14:617-27

- European Medicines Agency. European Medicines Agency gives new advice to better manage risk of adverse effects on the heart with Gilenya. European Medicines Agency, London, UK; 2012. p 1–2

- College voor Zorgverzekeringen. Medicijnkosten.nl. 2011. www.medicijnkosten.nl. Accessed June 22, 2012