Abstract

Objective:

To conduct a systematic literature review to assess burden of disease and unmet medical needs in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with constipation (IBS-C), with a focus on five European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, UK).

Methods:

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and grey literature searches were carried out using terms for IBS and constipation, to identify studies reporting epidemiological, clinical, humanistic, or economic outcomes for IBS-C, published between 2000 and 2010.

Results:

Searches identified 885 unique abstracts and 33 supplementary articles, of which 100 publications and six grey literature sources met the inclusion criteria. Among patients with IBS, the prevalence estimates of IBS-C ranged from 1 to 44%. Co-morbid conditions, such as personality traits, psychological distress, and stress, were common. Patients with IBS-C had lower health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) compared with the general population, and clinical trials suggested that effectively treating IBS-C improves HRQoL. The European societal cost of IBS-C is largely unknown, as no IBS-C-specific European cost-of-illness studies were identified. Two cost analyses demonstrated the substantial societal impact of IBS-C, including reduced productivity at work and work absenteeism. Guidelines offered similar recommendations for the diagnosis and management of IBS; however, recommendations specifically for IBS-C varied by country. Current IBS-C treatment options have limited efficacy and the risk:benefit profile of early 5-HT4 agonists restricts clinical use.

Conclusions:

This systematic review indicates a clear need for European-focused IBS-C burden-of-disease and cost-of-illness studies to address identified evidence gaps. There is a need for new therapies for IBS-C that are effective, well tolerated, and have a positive impact on HRQoL.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common, functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by chronic symptomatic episodes of abdominal pain or discomfort related to abnormal bowel movements, followed by periods of improvement and fewer, less severe, bowel symptomsCitation1. There is little consensus on the pathophysiology of IBS; however, it has been proposed that it results from a complex interaction of altered gut motility and transit, increased sensitivity of the colon or intestine, and psychological factors such as psychological distress, childhood trauma, and recent environmental stressCitation2,Citation3.

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported the global prevalence of IBS in 80 separate study populations containing 260,960 subjectsCitation4. Pooled prevalence in all studies was 11.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 9.8, 12.8)Citation4. The prevalence varied according to geographical location, including a prevalence of 12.0% (95% CI = 9.0, 15.0) in Northern Europe and 15.0% (95% CI = 11.0, 20.0) in Southern EuropeCitation4. IBS is more common in women than men, and people younger than 50 years of age are more likely to be affected than those over 50Citation5,Citation6. Additional risk factors may include certain foods, co-morbid psychological disorders, GI-related factors, smoking, and family history of IBSCitation7–10.

The diagnosis of IBS is based on patient-reported symptoms. According to the latest Rome III diagnostic criteria there are five sub-types of IBS: IBS with constipation (IBS-C); IBS with diarrhoea (IBS-D); IBS with mixed constipation and diarrhoea (IBS-M); IBS-M with alternating constipation and diarrhoea (IBS-A); and unsubtyped IBS (IBS-U)Citation1,Citation11–13. To meet the Rome III criteria, patients’ symptoms must have persisted for at least 6 months and be present at least 3 days per month before diagnosisCitation13.

IBS-C is the focus of the present review. It is characterized by hard or lumpy stools for 25% or more of bowel movements and loose or watery stools for fewer than 25% of bowel movements, with fewer than three bowel movements per weekCitation13. Symptoms of IBS-C include abdominal pain, discomfort, and bloatingCitation12. Furthermore, individuals with IBS-C often experience distress, dysfunction, and reduced productivity associated with the painful bowel disorderCitation14,Citation15. Therefore, from a societal perspective, cumulative work loss and healthcare resource utilization associated with IBS-C is likely to be significantCitation16,Citation17. Therapeutic targets for IBS-C have focused on stimulation of GI motor function, with the treatment goal being to improve bowel function and alleviate abdominal symptoms, especially pain and discomfort. However, currently, there are few effective and tolerable treatment options for IBS-CCitation1,Citation18, which may add to the economic burden of IBS-C.

Recent IBS review articles focus on discussing current pharmacological treatment developments for IBS-CCitation19–21 or do not separate IBS-C from IBSCitation22; there are a limited number of evidence-based reviews focusing specifically on the burden and management of IBS-C. Therefore, given that IBS-C accounts for one-third of patients with IBSCitation5 and is likely to be associated with a major impact on patient health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) and cost to society, we conducted a systematic review of the literature pertaining to the epidemiological, clinical, economic, and humanistic impact of IBS-C, to assess the burden of disease and unmet medical needs of patients with IBS-C. This review focused on five European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK), representing almost two-thirds of the total population of EuropeCitation23, as these countries often act as a reference for the other smaller European countries with regards to medical guidelines. Our aim was to improve understanding of the impact of IBS-C on patients and healthcare systems in Europe and identify needs currently unmet by treatment options.

Methods

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for the systematic literature review

Studies meeting all of the following criteria were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review: primary research studies published between January 2000 and December 2010 including more than 20 human subjects or review articles published between December 2007 and December 2010; studies with abstracts; studies reporting epidemiological, clinical, humanistic, or economic outcomes for IBS-C; and studies published in the English language. Studies that did not specify a population with the IBS sub-type IBS-C were excluded. In vitro, animal, foetal, molecular, genetic, and pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic studies were also excluded. Topics with geographic specificity (i.e. epidemiology, guidelines, practice patterns, and economic outcomes) were limited to studies in the five European countries of interest (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK).

Literature search

Systematic literature search

Published articles potentially reporting the disease burden of IBS-C were retrieved by searching MEDLINE and EMBASE. Searches were carried out in March 2011. Search strategies included terms for IBS and constipation. Specific limits for retrieving English-language studies conducted in humans published between January 2000 and December 2010 were applied to the searches. Additionally, bibliographies of review articles identified by the search were examined for relevant studies.

Abstracts were initially screened for suitability according to the specified inclusion/exclusion criteria, to determine whether the full-text publication should be retrieved for further review. A second reviewer screened 100% of the abstracts to minimize bias and ensure accuracy. Full-text publications were then examined for relevance for inclusion in the review by two reviewers. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by consensus. Positive exclusion was employed in the screening of articles so that only those that did not exhibit one or more of the inclusion criteria were excluded from the review. For outcomes for which the systematic literature review identified a lack of European studies with IBS-C specific data, European and non-European studies in patients with IBS (not specifically IBS-C) were included in the review.

Targeted non-English language literature search

In addition to the systematic searches described above, supplementary targeted literature searches of MEDLINE and EMBASE were performed to identify non-English language primary research studies, from France, Germany, Spain, and Italy, using the same criteria as the systematic literature search. Full-text publications were reviewed by native-language speakers to determine their relevance for inclusion in the review.

Grey literature search

Manual grey literature searches of relevant websites (gastroenterology societies, health organizations, health technology assessment bodies, clincaltrials.gov, and the Cochrane Library and Database of Systematic Reviews) were also performed to identify information on the burden of illness (including treatment guidelines) for IBS-C in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK, which was not published in peer-reviewed, indexed, medical journals. A full list of the grey literature searched is included in the Online Appendix.

Results

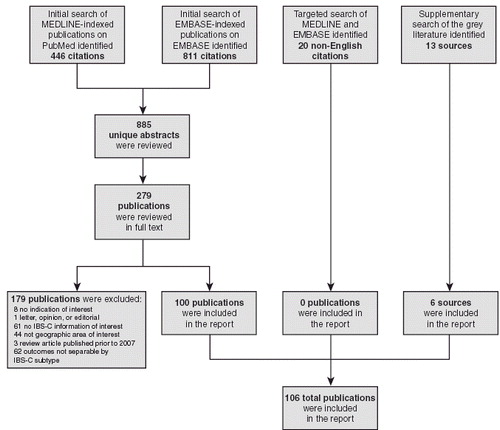

The systematic literature search identified 885 unique abstracts that were screened to assess their suitability for inclusion in the review. The number of articles proceeding at each stage of the review and reasons for exclusion are summarized in . A total of 279 full-text publications from the systematic literature search met the inclusion criteria for further review. Twenty non-English language articles were identified from the targeted literature search and 13 documents were retrieved from the grey literature searches. One hundred full-text publications from the systematic literature review and six documents from the grey literature search were selected for inclusion in the review. No publications from the non-English language search met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1. Number of articles proceeding at each stage of the systematic review. IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation.

The most common topics reported in the studies were treatment (38%) and definition/aetiology/diagnosis (32%) (). In the current article, we focus on reporting data on burden of illness, humanistic burden, economic burden, and treatment of IBS-C. Articles relating to definitions, aetiology and diagnosis are not discussed in detailCitation1,Citation7,Citation11–13,Citation24–54.

Table 1. Total number (%) of studies reporting data for different IBS-C topics.*

Burden of illness

Epidemiology

The prevalence of IBS-C among patients with IBS was reported in four studies, ranging from 1 to 24.1% in the UKCitation43,Citation55, to 34.6% in FranceCitation27, and 44% in SpainCitation56. No studies reporting the incidence of IBS-C were identified.

Risk factors

Two studies in patients with IBS reported personality traits, psychological distress, and stress as possible risk factors for IBS-C, compared with individuals with IBS-D or IBS-ACitation57 or non-IBS controlsCitation58. However, a conflicting study reported a greater prevalence of psychological and extra-intestinal symptoms in patients with IBS-A compared with those with IBS-C or IBS-DCitation59. In addition, a case-control study of 42 patients with IBS and 25 healthy controls demonstrated that a potential molecular biomarker, p11 (calpactin I light chain), was elevated in patients with IBS-CCitation60.

Humanistic burden

Between 2000 and 2010, 18 studies (most of which were prospective) have examined HRQoL and health states in patients with IBS-CCitation61–78. Instruments used to assess HRQoL included: general scales, such as the Short Form (SF)-36; GI disease scales, such as the GI Quality-of-Life (GIQLI) questionnaire; and disease-specific scales, including the IBS Quality-of-Life (IBS-QOL) and the Functional Digestive Disorders Quality-of-Life (FDDQL) questionnaires.

The IBS-QOL was the most frequently used HRQoL instrument, administered in eight of 18 studiesCitation61,Citation62,Citation64,Citation68–71,Citation77. Humanistic studies using the IBS-QOL to evaluate HRQoL in patients with IBS-C are presented in . Survey studies demonstrated that patients with IBS-C have diminished HRQoL compared with the general population, and clinical trials suggested that effectively treating IBS-C symptoms improves HRQoL. Five studies compared HRQoL impairment between IBS sub-typesCitation61,Citation63,Citation73,Citation74,Citation78. However, results were conflicting and no conclusion could be drawn as to whether patients with IBS-C have more or less HRQoL impairment than those with other IBS sub-types.

Table 2. Summary of humanistic studies using the IBS-QOL to evaluate HRQoL in patients with IBS-C.

Economic burden

Two analyses of work productivity in women with IBS-C treated with tegaserod, based on the same randomized controlled trial, were the only articles presenting data on the economic burden of IBS-C in Europe identified by the systematic review (). Tegaserod was reported to improve work productivity compared with baseline and placebo, including less impairment while at work (presenteeism), absence from work (absenteeism), and activity impairmentCitation15,Citation77. Reilly et al.Citation15 concluded that most patients seeking treatment for IBS-C have work and daily activity impairments, and relieving multiple symptoms of IBS may enhance patient wellbeing and improve their productivity.

Table 3. Studies evaluating economic burden associated with IBS-C.

No studies presenting the cost of illness, cost analyses, or resource use in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, or the UK were identified by the systematic review; therefore, economic studies in patients with IBS (not specifically IBS-C) were included in the review. A systematic review of studies in the US and UK examining direct and indirect costs of IBS, not specifically IBS-C, identified 18 relevant studies published between 1991 and 2003Citation79. Estimates of the total annual direct cost per patient for IBS ranged from US$348 to US$8750 (2002 costs), and total annual indirect cost per patient ranged from US$355 to US$3344Citation79. Additionally, the average number of days off work per year due to IBS was reported as 8.5–21.6 daysCitation79. Based on a prospective survey carried out in 2000 in France, investigations and hospitalizations accounted for most of the medical costs in patients with IBS. The highest costs were reported among elderly patients or patients with severe IBS symptoms, mainly pain. Patients with IBS for fewer than 5 years reported more frequent use of supplementary investigations than did patients with IBS for more than 5 yearsCitation80.

Treatment guidelines

Five clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of IBS published between 2000 and 2009 were identified by the systematic search, including: three UK guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)Citation81–83; one from a pan-European groupCitation84; and one from the World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO)Citation86. In addition, SpanishCitation85 and GermanCitation87 language guidelines, resulting from expert consensus groups, were identified as part of the grey literature search.

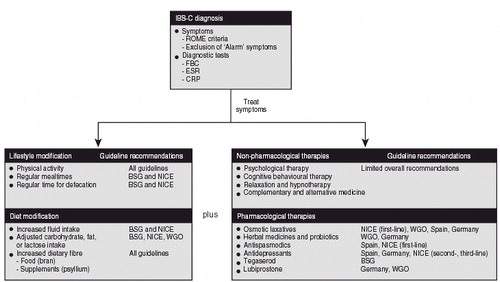

Taken together, these guidelines offered similar recommendations for the diagnosis and management of IBS; however, specific recommendations for the management of IBS-C varied by country. A summary of guideline recommendations for the treatment of IBS-C, identified by this systematic review, is provided in . Increased dietary fibre was almost universally recommended for the treatment of IBS-C; however, pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment recommendations varied.

Figure 2. Summary of treatment guideline recommendations for the management of IBS-C. ‘Alarm’ symptoms, symptoms that may suggest organic disease; BSG, British Society of Gastroenterology; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FBC, full blood count; IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; WGO, World Gastroenterology Organisation.

The use of psychological interventions (relaxation therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, hypnotherapy) was described in most of the guidelines identified by the systematic review; however, recommendations differed between guidelines and there were no specific recommendations for patients with IBS-CCitation81–83,Citation85,Citation86. In addition, the guidelines lacked information on complementary and alternative medicine approaches. Herbal medicines were only recommended in the most recent German guidelineCitation87. Similarly, probiotics, such as Bifidobacterium lactis, were suggested for IBS-C in the two most recent German and WGO guidelinesCitation85,Citation87. Laxatives were specifically recommended in the NICE, WGO, Spanish, and German guidelines for IBS-CCitation82,Citation85–87, but discouraged in an older guidelineCitation84. The NICE and Spanish guidelines also recommended anti-spasmodic agents, such as otilonium bromide and mebeverine, to treat pain and constipationCitation82,Citation86. In addition, antidepressant use in IBS-C was described in three guidelinesCitation82,Citation86,Citation87. While the NICE guidelines recommended tricyclic antidepressants as second-line therapy for IBS-CCitation82, the more recent German guideline advised against them as they are associated with constipationCitation87.

Two agents targeted specifically at IBS-C, tegaserod (approval withdrawn in the US and Switzerland in 2007 and now only available in the US as an investigational new drug, with its use restricted to women under the age of 55 with a low cardiovascular safety risk) and lubiprostone (approved in the US and in Switzerland for the treatment of chronic constipation in adult patients and the treatment of IBS-C in women only), were described in three guidelinesCitation83,Citation85,Citation87; the most recent German and WGO guidelines recommended lubiprostone for IBS-C treatmentCitation85,Citation87, and tegaserod was recommended as a second-line agent by the BSGCitation83.

Non-pharmacological therapies

Non-pharmaceutical treatment options for IBS-C include herbal formulations, fibre, probiotics, or symbiotic formulations. Two studies identified by the systematic review evaluated the safety and efficacy of herbal formulations for the treatment of IBS-C, demonstrating a reduction in IBS-C symptoms without any serious adverse eventsCitation88,Citation89. Further studies identified showed that fibreCitation90,Citation91 and probiotics or symbiotic formulationsCitation67,Citation92–95 may be beneficial to the symptoms of patients with IBS-C. No studies were identified by the systematic review that evaluated the safety and efficacy of psychological interventions for the treatment of IBS-C.

Pharmacological therapies

Although the clinical efficacy of laxatives for the treatment of IBS is well establishedCitation82, no studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of laxatives in patients with IBS-C were identified by the systematic review. In addition, no studies that evaluated the safety and efficacy of anti-spasmodics for the treatment of IBS-C were identified.

While the potential role for antidepressant therapy has been noted for IBS, only one study was identified by the systematic review that evaluated the effect of antidepressant agents specifically on IBS-C. In this study, abdominal discomfort, bloating, frequency of bowel movements, and stool consistency were improved in patients treated with fluoxetine compared with placeboCitation96.

As serotonin is a critical component in the regulation of gut motility, the systematic review found several studies that focused on targeting the serotonin receptor 5-HT4 in the treatment of IBS-C. 5-HT4 agonists evaluated for the treatment of IBS-C in the clinical studies identified included cisapride, tegaserod, and renzaprideCitation71,Citation77,Citation97–114. Tegaserod and renzapride demonstrated efficacy in providing relief of IBS symptomsCitation71,Citation111; however, both drugs have been associated with ischaemic colitis and tegaserod has been associated with a possible increased risk of serious cardiovascular events, which led to its withdrawal in 2007Citation71,Citation115. Cisapride demonstrated no substantial benefit in IBS-C compared with placeboCitation114 and was also withdrawn from the market following an association with rare dose-dependent cardiac events.

In addition, lubiprostone, a chloride channel activator, appeared to be effective in improving individual symptoms of IBS-C and was well toleratedCitation64,Citation69. Treatment with lubiprostone had no significant effect on patients’ quality-of-life (QoL), as evaluated by the IBS-QOL instrumentCitation64. Linaclotide, a minimally absorbed guanylate cyclase C agonist (GCCA), appeared to be well tolerated in patients with IBS-C, and was shown to improve bowel function and abdominal symptoms (including pain, bloating, and discomfort) and patients’ QoLCitation70,Citation116.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 106 studies reporting information on the burden of disease and unmet medical needs of patients with IBS-C. Most of these studies related to the diagnosis of IBS-C, its potential aetiology and clinical presentation, management guidelines, and treatment options, identifying a lack of published data relating to the burden of illness and economic burden of IBS-C from the European perspective. Indeed, economic studies in patients with IBS (not specifically IBS-C) were included in the review due to the dearth of European studies with IBS-C specific data.

The systematic review indicated a lack of studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of treatments prescribed for the symptoms of IBS-C (including laxatives, anti-spasmodics, and antidepressants) and the limited efficacy of current treatment options in alleviating the multiple symptoms of IBS-C. Therefore, there is a need for new therapies that are proven to be effective, well tolerated, and have a positive impact on HRQoL in patients with IBS-C. Indeed, several new treatment options for IBS-C are in development, including GCCAs and bile acid modulators; however, the GCCA, linaclotide, was the only drug currently in development for IBS-C that was identified by our systematic reviewCitation70,Citation116.

There is some discussion with regard to the validity and stability of the diagnosis of IBS-CCitation117–119. In the absence of defined pathophysiology of aetiology for IBS, symptom-based diagnosis criteria for IBS have evolved over time, with refinements in descriptions and duration of symptoms, since the Manning criteria developed in 1978 to the latest Rome III diagnostic criteriaCitation31,Citation37,Citation39,Citation51. Although there is evidence that patients can transition between different functional gastrointestinal disordersCitation118, a symptom-based diagnosis of the IBS sub-types aids effective treatment and management of patients with this condition. IBS-C is a recognized sub-type of IBS, with distinguishable diagnostic criteria to functional constipationCitation120. While there may be some symptom overlap between IBS-C and functional constipation or other IBS sub-types, to achieve positive outcomes for patients it is important that management approaches for IBS-C directly address the multiple overlapping symptoms of constipation, abdominal pain, discomfort, and bloating.

There is a lack of up-to-date treatment guidelines specific to the management of IBS-C. The systematic review found that the pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment recommendations varied between guidelines, which may be due to the availability of evidence at the time of publication of each guideline. Indeed, the later guidelines make recommendations for pharmacological agents in IBS-C based on the emergence of new evidence, new agents, and clinical experience.

Symptom-based management may, therefore, often be based on clinical opinion, so there is a need to develop evidence-based clinical guidelines to provide clinicians with up-to-date recommendations for the treatment of patients with IBS-C.

Although no cost-of-illness studies for IBS-C in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, or the UK were identified by this systematic review, studies in patients with IBS provide evidence that IBS contributes to both direct and indirect healthcare costs and is a cost-intensive disease, possibly as it is chronic and non-fatal, with a relatively high prevalence in working-age adults. Two analyses of a clinical trial identified by our systematic review, assessing work productivity related to IBS-C treatment, suggested that effectively treating the symptoms of IBS-C can reduce presenteeism, absenteeism, and activity impairmentCitation15,Citation77. Future research into the cost of illness for IBS and IBS-C is required to determine whether intensive consumption of healthcare resources is observed throughout Europe.

This systematic review did not identify any cost analyses for current IBS-C treatments from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, or the UK. However, a US model assessing the budgetary impact of tegaserod for IBS-C on a US managed-care organization (MCO) formulary, suggested that the use of tegaserod in women with IBS may be associated with reduced healthcare resource utilizationCitation121. The default 6-month cost of tegaserod was US$386.44 per patient (2003 costs) and the default MCO patient population was 10 million. The base-case model estimated an incremental per member per month budget impact of tegaserod use of US$0.01. For women with IBS, the calculated total cost per patient for the 6-month period was US$274.34, compared to US$301.84 for other GI diagnoses. In the IBS group, 29% of the cost of tegaserod was offset by reduced resource use; key drivers were fewer hospital stays (−US$38.61), outpatient office consultations (−US$18.20), and abdominal and pelvic computed tomographyCitation121.

In summary, our systematic review identified the need for more targeted research into IBS-C, to gain a better understanding of the specific disorder, treatment patterns, and the economic and humanistic burden to society, in order to address unmet patient needs.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Almirall.

Declaration of financial relationships

Josep Fortea and Mercedes Prior are employees of Almirall. JME Peer Reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ingela Wiklund, Talia Foster, and Karin Travers, who are employees of United Biosource Corporation, for their contribution to conducting this study. (Talia Foster was the Principal Investigator of the systematic literature search and Karin Travers was the Project Manager.) The authors would also like to thank Claire Chadwick, PhD, of Complete Clarity, who provided medical writing support funded by Almirall.

References

- Grundmann O, Yoon SL. Irritable bowel syndrome: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment: an update for health-care practitioners. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25:691-9

- Chang L. Review article: epidemiology and quality of life in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:31-9

- Quigley EM. Changing face of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:1-5

- Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:712-21

- Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, et al. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. American College of Gastroenterology IBS Task Force. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:S1-35

- Quigley EM, Bytzer P, Jones R, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: the burden and unmet needs in Europe. Dig Liver Dis 2006;38:717-23

- Foxx-Orenstein A. IBS - review and what’s new. MedGenMed 2006;8:20

- Park MI, Camilleri M. Is there a role of food allergy in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia? A systematic review. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2006;18:595-607

- Parry SD, Barton JR, Welfare MR. Factors associated with the development of post-infectious functional gastrointestinal diseases: does smoking play a role? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;17:1071-5

- Simrén M, Månsson A, Langkilde AM, et al. Food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion 2001;63:108-15

- Astegiano M, Pellicano R, Sguazzini C, et al. 2008 clinical approach to irritable bowel syndrome. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol 2008;54:251-7

- Cash BD, Chang E, Talley NJ, et al. Fresh perspectives in chronic constipation and other functional bowel disorders. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 2007;7:116-33

- Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480-91

- Leong SA, Borghout V, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic consequences of irritable bowel syndrome: a US employer perspective. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:929-35

- Reilly MC, Barghout V, McBurney CR, et al. Effect of tegaserod on work and daily activity in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;22:37-80

- Heitkemper MM, Jarrett ME. Update on irritable bowel syndrome and gender differences. Nutr Clin Pract 2008;23:275-83

- Spiegel BM. The burden of IBS: looking at metrics. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2009;11:265-9

- Harris LA, Crowell MD. Linaclotide, a new direction in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipation. Curr Opin Mol Ther 2007;9:403-10

- Roque MV, Camilleri M. Linaclotide, a synthetic guanylate cyclase C agonist for the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders associated with constipation. Exp Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;5:301-10

- Schey R, Rao SS. Lubiprostone for the treatment of adults with constipation and irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:1619-25

- Spiller RC. Targeting the 5-HT(3) receptor in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2011;11:68-74

- Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; preprintCD003460

- Eurostat. 2012. Total population 2012. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do;jsessionid=9ea7d07e30e987bc1b5a4ae246d9b450c41738acd4d9.e34OaN8Pc3mMc40Lc3aMaNyTaN0Re0?tab=table&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=tps00001. Accessed October 31, 2012

- Adeyemo MA, Spiegel BM, Chang L. Meta-analysis: do irritable bowel syndrome symptoms vary between men and women? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;32:738-55

- Agrawal A, Houghton LA, Reilly B, et al. Bloating and distension in irritable bowel syndrome: the role of gastrointestinal transit. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1998-2004

- Atkinson W, Lockhart S, Whorwell PJ, et al. Altered 5-hydroxytryptamine signaling in patients with constipation- and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2006;130:34-43

- Bommelaer G, Dorval E, Denis P, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in the French population according to the Rome I criteria. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2002;26:1118-23

- Camilleri M, McKinzie S, Busciglio I, et al. Prospective study of motor, sensory, psychologic, and autonomic functions in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;6:772-81

- Drossman DA. [Characterization of intestinal function and diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome by surveys and questionnaires]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1990;14:37C-41C

- Drossman DA, Morris CB, Hu Y, et al. A prospective assessment of bowel habit in irritable bowel syndrome in women: defining an alternator. Gastroenterology 2005;128:580-9

- Drossman DA. Introduction. The Rome Foundation and Rome III. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007;19:783-6

- Garrigues V, Mearin F, Badia X, et al. Change over time of bowel habit in irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective, observational, 1-year follow-up study (RITMO study). Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;25:323-32

- Gunnarsson J, Simren M. Efficient diagnosis of suspected functional bowel disorders. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;5:498-507

- Herman J, Pokkunuri V, Braham L, et al. Gender distribution in irritable bowel syndrome is proportional to the severity of constipation relative to diarrhea. Gend Med 2010;7:240-6

- Khan I, Hassan M, Rahman S. Frequency of organic pathologies in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. JPMI 2009;23:341-6

- Khan S, Chang L. Diagnosis and management of IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;7:565-81

- Kruis W, Thieme C, Weinzierl M, et al. A diagnostic score for the irritable bowel syndrome. Its value in the exclusion of organic disease. Gastroenterology 1984;87:1-7

- Mann NS, Limoges-Gonzales M. The prevalence of small intestinal bacterial vergrowth in irritable bowel syndrome. Hepatogastroenterology 2009;56:718-21

- Manning AP, Thompson WG, Heaton KW, et al. Towards positive diagnosis of the irritable bowel. Br Med J 1978;2:653-4

- Mearin F, Baro E, Roset M, et al. Clinical patterns over time in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom instability and severity variability. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:113-21

- Naliboff BD, Berman S, Suyenobu B, et al. Longitudinal change in perceptual and brain activation response to visceral stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Gastroenterology 2006;131:352-65

- Palsson OS, Drossman DA. Psychiatric and psychological dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome and the role of psychological treatments. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005;34:281-303

- Penny KI, Smith GD, Ramsay D, et al. An examination of subgroup classification in irritable bowel syndrome patients over time: a prospective study. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:1715-20

- Sadik R, Bjornsson E, Simren M. The relationship between symptoms, body mass index, gastrointestinal transit and stool frequency in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;22:102-8

- Sperber AD, Shvartzman P, Friger M, et al. A comparative reappraisal of the Rome II and Rome III diagnostic criteria: are we getting closer to the ‘true' prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;19:441-7

- Spiegel BM, Farid M, Esrailian E, et al. Is irritable bowel syndrome a diagnosis of exclusion?: a survey of primary care providers, gastroenterologists, and IBS experts. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:848-58

- Steens J, Van Der Schaar PJ, Penning C, et al. Compliance, tone and sensitivity of the rectum in different subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2002;14:241-7

- Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Melton LJ, et al. Diagnostic value of the Manning criteria in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 1990;31:77-81

- Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, III. Irritable bowel syndrome in a community: symptom subgroups, risk factors, and health care utilization. Am J Epidemiol 1995;142:76-83

- Talley NJ, Li Z. Helicobacter pylori: testing and treatment. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;1:71-9

- Thompson WG. The road to Rome. Gut 1999;45(2 Suppl):II80

- Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Feld AD, et al. Utility of red flag symptom exclusions in the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24:137-46

- Zar S, Benson MJ, Kumar D. Rectal afferent hypersensitivity and compliance in irritable bowel syndrome: differences between diarrhoea-predominant and constipation-predominant subgroups. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;18:151-8

- Zhan L, Zhou D, Xu GM, et al. Study on functional constipation and constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome by using the colonic transit test and anorectal manometry. Chin J Dig Dis 2002;3:128-31

- Wilson S, Roberts L, Roalfe A, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: a community survey. Br J Gen Pract 2004;54:495-502

- Mearin F, Balboa A, Badia X, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes according to bowel habit: revisiting the alternating subtype. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;15:16-72

- Farnam A, Somi MH, Sarami F, et al. Personality factors and profiles in variants of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:6414-8

- Hertig VL, Cain KC, Jarrett ME, et al. Daily stress and gastrointestinal symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Nurs Res 2007;56:399-406

- Tillisch K, Labus JS, Naliboff BD, et al. Characterization of the alternating bowel habit subtype in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:896-904

- Camilleri M, Andrews CN, Bharucha AE, et al. Alterations in expression of p11 and SERT in mucosal biopsy specimens of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2007;132:17-25

- Amouretti M, Le Pen C, Gaudin AF, et al. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) on health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2006;30:241-6

- Cain KC, Headstrom P, Jarrett ME, et al. Abdominal pain impacts quality of life in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:124-32

- Coffin B, Dapoigny M, Cloarec D, et al. Relationship between severity of symptoms and quality of life in 858 patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2004;28:11-15

- Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF, et al. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome - results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:329-41

- Ducrotte P, Dapoigny M, Bonaz B, et al. Symptomatic efficacy of beidellitic montmorillonite in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;21:435-44

- Eriksson EM, Andrén KI, Eriksson HT, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes differ in body awareness, psychological symptoms and biochemical stress markers. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:4889-96

- Guyonnet D, Chassany O, Ducrotte P, et al. Effect of a fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium animalis DN-173 010 on the health-related quality of life and symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome in adults in primary care: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;26:475-86

- Hawkes ND, Rhodes J, Evans BK, et al. Naloxone treatment for irritable bowel syndrome – a randomized controlled trial with an oral formulation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:1649-54

- Johanson JF, Drossman DA, Panas R, et al. Clinical trial: phase 2 study of lubiprostone for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;27:685-96

- Johnston JM, Kurtz CB, Macdougall JE, et al. Linaclotide improves abdominal pain and bowel habits in a Phase IIb study of patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Gastroenterology 2010;139:1877-86

- Lembo AJ, Cremonini F, Meyers N, et al. Clinical trial: renzapride treatment of women with irritable bowel syndrome and constipation - a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;31:979-90

- Muscatello MR, Bruno A, Pandolfo G, et al. Depression, anxiety and anger in subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome patients. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2010;17:64-70

- Si JM, Wang LJ, Chen SJ, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome consulters in Zhejiang province: the symptoms pattern, predominant bowel habit subgroups and quality of life. World J Gastroenterol 2004;10:1059-64

- Simrén M, Abrahamsson H, Björnsson ES. An exaggerated sensory component of the gastrocolonic response in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2001;48:20-7

- Spiegel B, Camilleri M, Bolus R, et al. Psychometric evaluation of patient-reported outcomes in irritable bowel syndrome randomized controlled trials: a Rome Foundation report. Gastroenterology 2009;137:1944-53.e1–3

- Spiegel B, Harris L, Lucak S, et al. Developing valid and reliable health utilities in irritable bowel syndrome: results from the IBS PROOF Cohort. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1984-91

- Tack J, Müller-Lissner S, Bytzer P, et al. A randomised controlled trial assessing the efficacy and safety of repeated tegaserod therapy in women with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Gut 2005;54:1707-13

- Zhao Y, Zou D, Wang R, et al. Dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome in China: a population-based endoscopy study of prevalence and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;32:562-72

- Maxion-Bergemann S, Thielecke F, Abel F, et al. Costs of irritable bowel syndrome in the UK and US. Pharmacoeconomics 2006;24:21-37

- Le Pen C, Ruszniewski P, Gaudin AF, et al. The burden cost of French patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004;39:336-43

- Jones J, Boorman J, Cann P, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for the management of the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2000;47(2 Suppl):ii1-19

- National Collaborating Centre for Nursing and Supportive Care, on behalf of NICE, 2008. Clinical practice guideline. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management of irritable bowel syndrome in primary care. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK51953. Accessed July 24, 2012

- Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut 2007;56:1770-98

- Thompson WG, Hungin AP, Neri M, et al. The management of irritable bowel syndrome: a European, primary and secondary care collaboration. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001;13:933-9

- World Gastroenterology Organisation. Irritable bowel syndrome: a global perspective. Milwaukee, WI, USA. 2009. http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/assets/downloads/en/pdf/guidelines/20_irritable_bowel_syndrome.pdf. Accessed July 24 2012

- Tort S, Balboa A, Marzo M, et al. [Clinical practice guideline for irritable bowel syndrome]. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;29:467-521

- Layer P, Andresen V, Pehl C, et al. [Irritable bowel syndrome: German consensus guidelines on definition, pathophysiology and management]. Z Gastroenterol 2011;49:237-93

- Hawrelak JA, Myers SP. Effects of two natural medicine formulations on irritable bowel syndrome symptoms: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med 2010;16:1065-71

- Sallon S, Ben-Arye E, Davidson R, et al. A novel treatment for constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome using Padma Lax, a Tibetan herbal formula. Digestion 2002;65:161-71

- Parisi GC, Zilli M, Miani MP, et al. High-fiber diet supplementation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a multicenter, randomized, open trial comparison between wheat bran diet and partially hydrolyzed guar gum (PHGG). Dig Dis Sci 2002;47:1697-704

- Tarpila S, Tarpila A, Grohn P, et al. Efficacy of ground flaxseed on constipation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Top Nutraceutical Res 2004;2:119-25

- Agrawal A, Houghton LA, Morris J, et al. Clinical trial: the effects of a fermented milk product containing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010 on abdominal distension and gastrointestinal transit in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:104-14

- Colecchia A, Vestito A, La Rocca A, et al. Effect of a symbiotic preparation on the clinical manifestations of irritable bowel syndrome, constipation-variant. Results of an open, uncontrolled multicenter study. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol 2006;52:349-58

- Dughera L, Elia C, Navino M, et al. Effects of symbiotic preparations on constipated irritable bowel syndrome symptoms. Acta Biomed 2007;78:111-6

- Martens U, Enck P, Zieseniss E. Probiotic treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in children. Ger Med Sci 2010;8:Doc07

- Vahedi H, Merat S, Rashidioon A, et al. The effect of fluoxetine in patients with pain and constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind randomized-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;22:381-5

- Camilleri M, McKinzie S, Fox J, et al. Effect of renzapride on transit in constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:895-904

- Chey WD, Paré P, Viegas A, et al. Tegaserod for female patients suffering from IBS with mixed bowel habits or constipation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1217-25

- Di Stefano M, Miceli E, Mazzocchi S, et al. Effect of tegaserod on recto-sigmoid tonic and phasic activity in constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1720-6

- Fisher RS, Thistle J, Lembo A, et al. Tegaserod does not alter fasting or meal-induced biliary tract motility. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1342-9

- Foxx-Orenstein AE, Camilleri M, Szarka LA, et al. Does co-administration of a non-selective opiate antagonist enhance acceleration of transit by a 5-HT4 agonist in constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome? A randomized controlled trial. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007;19:821-30

- George AM, Meyers NL, Hickling RI. Clinical trial: renzapride therapy for constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome - multicentre, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study in primary healthcare setting. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;27:830-7

- Harish K, Hazeena K, Thomas V, et al. Effect of tegaserod on colonic transit time in male patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:1183-9

- Khoshoo V, Armstead C, Landry L. Effect of a laxative with and without tegaserod in adolescents with constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23:191-6

- Layer P, Keller J, Mueller-Lissner S, et al. Tegaserod: long-term treatment for irritable bowel syndrome patients with constipation in primary care. Digestion 2005;71:238-44

- Li Y, Nie Y, Xie J, et al. The association of serotonin transporter genetic polymorphisms and irritable bowel syndrome and its influence on tegaserod treatment in Chinese patients. Dig Dis Sci 2007;52:2942-9

- Müller-Lissner S, Holtmann G, Rueegg P, et al. Tegaserod is effective in the initial and retreatment of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;21:11-20

- Novick J, Miner P, Krause R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tegaserod in female patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:1877-88

- Prather CM, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Tegaserod accelerates orocecal transit in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2000;118:463-8

- Sabaté JM, Bouhassira D, Poupardin C, et al. Sensory signalling effects of tegaserod in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2008;20:134-41

- Shah SH, Jafri SW, Gul M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of tegaserod in constipation dominant irritable bowel syndrome. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2004;14:21-4

- Tack J, Middleton SJ, Horne MC, et al. Pilot study of the efficacy of renzapride on gastrointestinal motility and symptoms in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23:1655-65

- Tougas G, Snape WJ Jr., Otten MH, et al. Long-term safety of tegaserod in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:1701-8

- Ziegenhagen DJ, Kruis W. Cisapride treatment of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome is not superior to placebo. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;19:744-9

- Food and Drug Administration. Public Health Advisory: Tegaserod maleate (marketed as Zelnorm). Silver Spring, MD, USA. 2007. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm051284.htm. Accessed July 20, 2012

- Andresen V, Camilleri M, Busciglio IA, et al. Effect of 5 days linaclotide on transit and bowel function in females with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2007;133:761-8

- Ford AC. Overlap among the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:2512

- Halder SL, Locke GR, III, Schleck CD, et al. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology 2007;133:799-807

- Wong RK, Palsson OS, Turner MJ, et al. Inability of the Rome III criteria to distinguish functional constipation from constipation-subtype irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:2228-34

- Rome Foundation. Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Raleigh, NC, USA. 2012. http://www.romecriteria.org/assets/pdf/19_RomeIII_apA_885-898.pdf. Accessed December 13, 2012

- Bloom MA, Barghout V, Kahler KH, et al. Budget impact of tegaserod on a managed care organization formulary. Am J Manag Care 2005;11:S27-S34