Abstract

Objective:

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease that can affect multiple organ systems, including the kidneys (lupus nephritis) and the central nervous system (neuropsychiatric lupus, or NPSLE). The healthcare costs and resource utilization associated with treating lupus nephritis and NPSLE in a large US managed care plan were studied.

Methods:

SLE subjects ≥18 years of age and with claims-based evidence of nephritis or neuropsychiatric conditions were identified from a health plan database. An index date was set as a randomly drawn date from all qualifying claims during 2003–2008 for study subjects. Subjects were matched on the basis of demographic and clinical characteristics to unaffected controls. Costs and resource use were determined during a fixed 12-month post-index period.

Results:

Nine hundred and seven lupus nephritis subjects were matched to controls, and 1062 subjects with NPSLE were matched to controls. Mean overall post-index healthcare costs were significantly higher among subjects with lupus nephritis in comparison to matched controls ($33,472 vs $5347, p < 0.001). Similarly, mean overall post-index healthcare costs were significantly higher among subjects with NPSLE compared to controls ($30,341 vs $4646, p < 0.001). Subjects with lupus nephritis or NPSLE had higher mean post-index numbers of ambulatory visits, specialist visits, emergency department visits and inpatient hospital stays, compared to controls (all p < 0.001).

Limitations:

Additional research, such as medical chart review, could provide validation for the claims-based identification of lupus nephritis and NPSLE subjects. Also, indirect costs were not evaluated in this study.

Conclusion:

Subjects with lupus nephritis or NPSLE have high costs and resource use, compared to unaffected controls.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease with a heterogeneous clinical presentation. Signs and symptoms include skin rashes, serositis, photosensitivity, and feverCitation1,Citation2.

Lupus nephritis affects ∼30% of SLE patients, typically develops early in the disease course, and is a major cause of morbidity and mortalityCitation3,Citation4. Lupus nephritis is often asymptomatic until the disease is advanced, and treatments include immunosuppressive drugs, dialysis, or renal transplantCitation5,Citation6.

At least 20% of SLE patients develop some form of neuropsychiatric disease (NPSLE)Citation3. NPSLE can have a major impact on patient functioning, causing seizures, psychosis, chronic headache, and neural cognitive dysfunctionCitation7. Therapy for NPSLE may include high dose corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, anti-convulsants, antidepressants, or anti-psychoticsCitation6,Citation8.

In a prior analysis, we reported on the resource use of SLE subjects, and found that direct costs for patients with existing SLE in an insured commercial plan were $15,487Citation9, ∼3-fold higher than patients without SLE. In this study, we investigated the costs and resource utilization associated with lupus nephritis and NPSLE in a US insurance claims database. While a few studies have reported on costs associated with lupus nephritisCitation10–14, little data exist on costs and resource use associated with NPSLECitation15. To ensure that results from this study would be representative of all stages of disease (and not just the initial stage), we used a prevalent approach to identify subjects. Therefore, the subjects selected were not limited to those who were newly diagnosed as per previous studies reporting costs associated with lupus nephritis, but included subjects who may have had chronic or newly active disease. Also, in order to broadly select as many lupus nephritis or NPSLE subjects as possible, no temporal restriction was placed on the relationship between the SLE diagnosis date and the nephritis or neuropsychiatric diagnosis date (especially as these diagnoses may occur at different times in a real word setting). Costs of subjects with existing disease were compared to costs of individuals unaffected with SLE.

Patients and methods

Subject identification

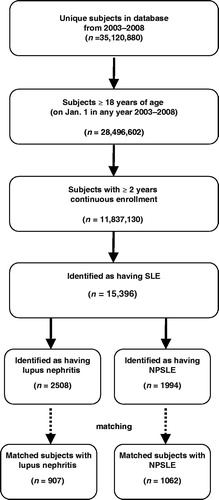

The identification of subjects with lupus nephritis and NPSLE was a multi-step process. In the first step, we identified subjects with existing (prevalent) SLE from a claims database described below. In the second step, subjects with lupus nephritis and NPSLE were selected from the population of SLE subjects. In the third step, lupus nephritis and NPSLE subjects were matched to controls unaffected with SLE.

SLE identification

Eligible enrollees were from a national managed care organization (MCO) consisting of ∼35 million commercially insured members with medical and pharmacy benefits during the study period from 2003–2008 (and ∼14 million total covered lives per year). The MCO provided full insurance coverage for physician, hospital, and pharmacy services. The MCO population was fairly representative of the US population in terms of age, gender, and geographic distribution (slight under-representation of the Northeast and West regions, slight over-representation of the Midwest and Southern region and slight under-representation of the elderly [65+]), based on empirical comparison between total lives (2008) in the MCO database with 2008 US statistical abstract data. Previous studies have validated the use of claims-based algorithms to identify disease in a database affiliated with this MCOCitation16. Although the use of such an algorithm to identify patients with SLE in this database has not been validated, studies in other databases have adequately demonstrated that claims-based algorithms could identify patients with lupus nephritis and other chronic medical conditions (such as arthritis)Citation17,Citation18.

Subjects with SLE were identified from the database using claims data. Study subjects were required to have a date of service of a medical claim with a diagnosis code for SLE from 1 January 2003 through 31 December 2008 that satisfied the following inclusion criteria: (1) the subject was at least 18 on the date of service; (2) the subject was continuously enrolled with medical and pharmacy benefits for 12 months prior to and following the date of service; and (3) in the 12 months following the date of service the subject had either (3a) evidence of at least one inpatient claim with a SLE diagnosis (ICD-9-CM 710.0x) or (3b) two or more office or ER visits (combinations allowed) at least 30 days apart, but not more than 365 days apart, with a diagnosis code for SLE (where the first visit occurred during the same calendar year as the date of service). An index date for SLE subjects was assigned randomly from all qualifying service dates between 2003–2008. The identification approach used here was a prevalent approach, and was designed to identify subjects with either newly diagnosed or already existing disease.

Nephritis and neuropsychiatric cohorts

All SLE subjects were eligible to be assigned to a lupus nephritis and/or NPSLE cohort. When assigning subjects to these cohorts, nephritis and NPSLE claims were considered separately. Therefore, the cohorts are not mutually exclusive, and a subject could be assigned to both cohorts if all criteria were met independently for both nephritis claims and NPSLE claims. The nephritis and NPSLE diagnosis claims used for this study were selected following consultation with a variety of prior studies, including codes used by Li et al.Citation10 for identification of nephritis, ACR case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupusCitation7, and conditions in the SLEDAI scale (which was used for identification of NPSLE)Citation19. Inclusion in a lupus nephritis cohort or a NPSLE cohort required a date of service of a medical claim with a nephritis diagnosis (acute glomerulonephritis, nephrotic syndrome, chronic glomerulonephritis, nephritis unspecified, acute renal failure, chronic kidney disease, renal failure, kidney biopsy, hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, kidney transplant) or a neuropsychiatric (NP) diagnosis (seizure, psychosis, organic brain syndrome, cranial nerve disorder, demyelination syndromes, encephalitis, myelitis, encephalomyelitis, myelopathy, aseptic meningitis, cerebral vasculitis, mononeuritis multiplex, plexus disorders) from 1 January 2003 through 31 December 2008 that met the following cohort criteria: (1) the subject was at least 18 on the date of service of the nephritis or neuropsychiatric diagnosis; (2) the subject was continuously enrolled with medical and pharmacy benefits for 12 months prior to and following the date of service of the nephritis or neuropsychiatric diagnosis; and (3) in the 12 months following the date of service of the nephritis or neuropsychiatric diagnosis the subject had either (3a) evidence of at least one inpatient claim with a nephritis or neuropsychiatric diagnosis or (3b) two or more office or ER visits (combinations allowed) at least 30 days apart with a nephritis or neuropsychiatric diagnosis code (where the first visit occurred during the same calendar year as the date of service) or (3c) evidence of at least one medical claim with a nephritis procedure code at any site of service (nephritis cohort only; Supplemental Table 1). Subjects could qualify for the study regardless of whether the nephritis and/or NP diagnosis occurred before or after the SLE diagnosis, as long as all diagnoses occurred within the study time frame (2003–2008).

Matching

Lupus nephritis and NPSLE subjects were matched to controls, which consisted of commercial health plan enrollees without evidence of SLE. The ‘matching date’ for subjects with SLE was defined as the index date. For controls, a matching date was selected randomly from within each control subject’s enrollment period with the qualification that the subject would have at least 1 year of enrollment before and after the date. To be eligible for selection, controls were required to be age 18 or older as of the year of the matching date, to have at least one office visit from 1 January 2003 through 31 December 2008, to have continuous enrollment with medical and pharmacy benefits for at least 24 months during 2003–2008, and to have no diagnosis claims for SLE (ICD-9-CM 710.0x), myositis (ICD-9-CM 710.3, 710.4, 728.81), or systemic sclerosis (ICD-9-CM 710.1x), during the continuous enrollment period. The requirement to have no diagnosis claims for these connective tissue disorders was imposed in order to avoid a confounding effect on the results, as they tend to overlap with SLE and can be misclassified. However, it is possible that some control cohort subjects may have had evidence of other connective tissue diseases that were not specifically excluded by the above criteria.

Lupus nephritis and NPSLE subjects were matched to eligible controls in a 2-step process. In the first step, lupus nephritis and NPSLE subjects were matched to controls using a ratio of 1:5 based on the following criteria: matching date (±6 months); age (±5 years); gender; geographic region; and length of time on insurance (±5 years). In the second step, lupus nephritis and NPSLE subjects were matched to the sub-set of controls selected in the first step using a ratio of 1:3, based on Quan-Charlson comorbidity score (±1.0). Subjects that could not be matched to five controls in step 1 or to three controls in step 2 were excluded.

Age, gender, and geographic region (Northeast, South, West, or Midwest) were captured from enrollment data based on the SLE claim associated with index date. Comorbidities of interest were identified based on the presence of diagnosis codes on medical claims during the 1 year prior to (but not including) the SLE index date. A Quan-Charlson comorbidity score was calculated using pre-index comorbiditiesCitation20.

Costs and resource utilization

Healthcare costs and resource utilization were measured for a fixed 1-year post-index period (including the index date). Healthcare costs were computed as the combined health plan and patient paid amounts; in addition, payments from Medicare (or other payers) were estimated based on co-ordination of benefits information obtained by the health plan, and these estimates were incorporated into the total paid amount. The following cost variables were calculated: pharmacy costs, ambulatory costs, emergency services costs, inpatient costs, other costs, and total costs (which were computed as the combination of the other five cost categories). Costs were adjusted to 2009 US$ using the annual medical care component of the Consumer Price Index. All procedures and doctor visits that occurred during an ambulatory visit, emergency department visit, or inpatient admission were included in the costs for that particular visit or admission; pharmacy claims for medications were included in the pharmacy costs category.

Healthcare resource utilization was operationalized as the numbers of the following: ambulatory visits, emergency department visits, and inpatient admissions. The average total length of inpatient stays was also calculated. Evidence of services rendered by specific physician specialties (rheumatologist, dermatologist, neurologist, or nephrologist) was captured. Evidence of use of selected procedures (diagnostic services or durable medical equipment) was determined; these may have occurred during ambulatory visits, physician visits, emergency department visits, or inpatient stays. Medications of interest were identified from pharmacy claims (using National Drug Code [NDC] code bundles) and medical claims (using appropriate Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] codes submitted by individual providers which use the Health Care Financing Administration [HCFA]-1500 or Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS]-1500 formats or for facility services submitted by institutions, which use the Uniform Bill [UB]-82, UB-92, UB-04, or CMS-1450 formats).

Costs and resource utilization were compared between lupus subjects and controls using logistic regression for binary variables and a generalized linear model for continuous variables unadjusted for other independent variables. Multivariate methods were employed to account for the correlated nature of the matched data by using generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with an exchangeable correlation matrix. Reported p-values for both types of variables were based on Wald tests.

Results

Lupus nephritis

After matching on the basis of clinical and demographic characteristics, 907 SLE subjects were identified to have nephritis and fit the lupus nephritis definition in the study (). About 88% of these subjects were female and ∼50% were 18–44 years of age. A significantly higher proportion of lupus nephritis subjects than matched controls had evidence of cataract (p = 0.016), cardiovascular disease (p < 0.001), osteoporosis (p < 0.001), avascular necrosis (p < 0.001), osteoarthritis (p < 0.001), and hypertension (p < 0.001) (). However, diabetes (p < 0.001) and malignancy (p = 0.023) were observed among a higher proportion of controls than lupus nephritis subjects. As described earlier, matching was performed using a Quan-Charlson comorbidity score, not using individual comorbidities; therefore, it is not unexpected that certain individual comorbidities were more common among controls than subjects (and vice versa). However, the comorbidities that were more frequent among the controls than the subjects (diabetes and malignancy) were only higher by a few percentage points.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of lupus nephritis subjects and matched controls (2003–2008).

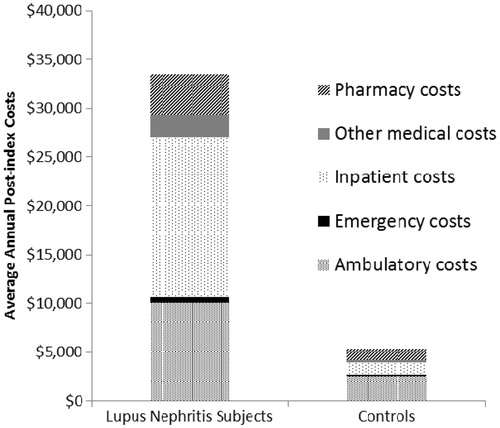

Mean overall annual (post-index) healthcare costs were significantly higher among lupus nephritis subjects than matched controls ($33,472 [95% CI = $29,797–$37,146] vs $5347 [95% CI = $4719–$5976], p < 0.001). Overall costs of lupus nephritis subjects were examined in more detail by breaking costs down into several sub-categories: mean annual (post-index) inpatient costs were $16,474, mean annual ambulatory costs were $10,083, mean annual pharmacy costs were $4188, and mean annual emergency services costs were $518 ().

Figure 2. Average annual component costs of lupus nephritis subjects and matched controls (2003–2008).

On average, subjects with lupus nephritis also had higher levels of healthcare resource use during the post-index period than matched controls. Lupus nephritis subjects had higher use of ambulatory visits, primary care physician visits, nephrologist visits, neurologist visits, rheumatologist visits, dermatologist visits, emergency department visits, and inpatient hospital stays than matched controls (all p < 0.001) (). Also, higher proportions of lupus nephritis subjects than matched controls had claims for systemic corticosteroids, methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, antimalarials, and rituximab (all p < 0.001) ().

Table 2. Annual (post-index) healthcare resource use of lupus nephritis subjects and matched controls (2003–2008).

NPSLE

After matching on the basis of clinical and demographic characteristics, 1062 SLE subjects fulfilled the study definitions of NPSLE (). About 93% of these subjects were female and ∼49% were 45–64 years of age (). A significantly higher proportion of NPSLE subjects than matched controls had evidence of cataract (p < 0.001), cardiovascular disease (p < 0.001), osteoporosis (p < 0.001), avascular necrosis (p = 0.004), osteoarthritis (p < 0.001), hypertension (p < 0.001), depression (p < 0.001), and cerebrovascular events (p < 0.001) (). However, diabetes (p < 0.001) and malignancy (p = 0.010) were observed among a higher proportion of controls than NPSLE subjects. Similar to the lupus nephritis controls, the actual percentage of these comorbidities that were higher in the control cohort were higher by a few percentage points.

Table 3. Demographic characteristics of NPSLE subjects and matched controls (2003–2008).

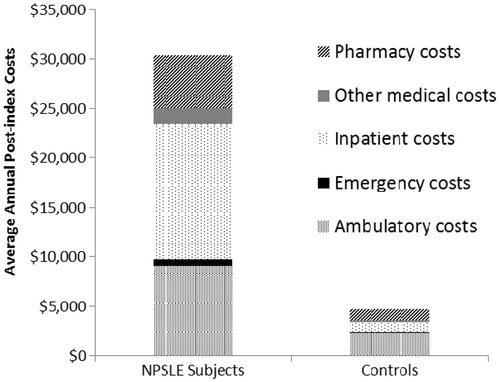

Mean overall annual (post-index) healthcare costs were significantly higher among NPSLE subjects than matched controls ($30,341 [95% CI = $27,209–$33,474] vs $4646 [95% CI = $4297–$4995], p < 0.001). When costs were calculated by sub-category, mean annual (post-index) inpatient costs among NPSLE subjects were $13,778, mean annual ambulatory costs were $9077, mean annual pharmacy costs were $5371, and mean annual emergency services costs were $610 ().

On average, subjects with NPSLE also had significantly higher levels of healthcare resource use during the post-index period than matched controls. NPSLE subjects had higher use of ambulatory visits, primary care physician visits, nephrologist visits, neurologist visits, rheumatologist visits, dermatologist visits, emergency department visits, and inpatient hospital stays than matched controls (all p < 0.001) (). Also, higher proportions of NPSLE subjects than matched controls had claims for systemic corticosteroids (p < 0.001), methotrexate (p < 0.001), azathioprine (p < 0.001), cyclophosphamide (p < 0.001), mycophenolate mofetil (p < 0.001), anti-malarials (p < 0.001), and rituximab (p = 0.026) ().

Table 4. Annual (post-index) healthcare resource use of NPSLE subjects and matched controls (2003–2008).

Discussion

In this analysis, we used a large managed care population to estimate healthcare costs of SLE subjects with renal or NP involvement. Overall average annual healthcare costs for subjects with lupus nephritis were $33,472 (95% CI = $29,797–$37,146). For NPSLE subjects, overall average annual healthcare costs were $30,341 (95% CI = $27,209–$33,474). Both lupus nephritis and NPSLE were associated with substantively and significantly higher costs (by 6–7-fold) when compared to unaffected controls. Inpatient costs made up the largest portion of overall medical costs among both lupus nephritis and NPSLE subjects. Previously we reported that average annual healthcare costs were $15,487 (95% CI = $14,785–$16,189) among subjects with existing SLE in a US managed care populationCitation9. In line with clinical expectations, presence of renal or NP involvement in SLE does increase economic burden.

In the present study, both lupus nephritis and NPSLE subjects had on average higher levels of resource utilization such as numbers of primary care physician visits, specialist visits, emergency department visits, and inpatient hospital stays than matched controls. Although we did not compare the lupus nephritis and NPSLE cohorts directly, some empirical comparisons can be made to corroborate whether our approach of identifying the patients was effective in selecting appropriate populations from a clinical perspective. As expected, lupus nephritis patients had more nephrologist visits (∼35% of lupus nephritis subjects had a nephrologist visit), whereas NPSLE patients had more neurologist visits (∼33% of NPSLE subjects had a neurologist visit). Both NPSLE and lupus nephritis subjects had high numbers of rheumatologist visits. NPSLE subjects tended to have a higher prevalence of depression, while hypertension was more prevalent in lupus nephritis subjects. Of the medications examined in the study, both lupus nephritis and NPSLE cohorts had comparable proportions of subjects on anti-malarials and systemic corticosteroids; however, mycophenolate mofetil appeared to be prescribed more commonly among lupus nephritis subjects than NPSLE subjects. Thus, each individual cohort (LN and NPSLE) appeared to reflect characteristics expected from LN and NPSLE patients.

However, as an immunosuppressant/corticosteroid combination is indicated for acute lupus nephritis, our results suggest that not all subjects in the lupus nephritis cohort had active lupus nephritis (∼45% of lupus nephritis subjects were prescribed either mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, or rituximab, and only ∼68% were prescribed systemic corticosteroids). Similar supposition can be made about the NPSLE patients too (<25% immunosuppressant use and 60% systemic corticosteroid use).

Our findings are similar to those reported by Pelletier et al.Citation11, who reported annual costs of $30,652 (2008 dollars) for lupus nephritis patients in a US commercial insurance claims database from 2007–2008. However, they appear to be lower than those reported by Carls et al.Citation12, who found that SLE subjects with nephritis had annual medical expenditures of $58,389 (2005 dollars) during 2000–2005. This could be due to different benefit designs in the commercial plans evaluated; Carls et al.Citation12 had more patients enrolled in indemnity plans vs health maintenance organization (HMOs), which tend to have higher costsCitation21. Also, Carls et al.Citation12 used an incident cohort for evaluating costs based on newly active disease, whereas our study used a prevalent cohort for evaluating costs. It is likely that differences exist in the way that patients with newly active disease are managed, compared with how patients with established disease are managed. Incident patients have more active disease which requires aggressive diagnosis and management; in more chronic disease, there is likely lower utilization of diagnostic resources and possibly less intensive pharmacotherapy. A similar analysis in Medicaid by Li et al.Citation10 reported annual medical costs of $27,463 in the first year for newly active lupus nephritis patients which increased to $50,578 5 years (2006 dollars) after diagnosis. However, direct comparison of Medicaid and Commercial patients is difficult due to differences in access to care, which could result in differences in health status (for example, management of Medicaid patients may be delayed, leading to a higher number progressing to renal failure, which requires costly treatment). All three studiesCitation10–12 have also reported increased healthcare resource utilization in lupus nephritis patients. Similar to the present study, Carls et al.Citation12 reported that inpatient admissions represented the largest portion of overall annual costs among subjects with existing lupus nephritis. In contrast, Pelletier et al.Citation11 and Li et al.Citation10 found that outpatient care represented the largest portion of costs among lupus nephritis subjects. These differences could be due to differences in practice patterns across the populations evaluated, and there may also be differences in how costs are grouped and categorized in these studies (for example, Pelletier et al.Citation11 included emergency department visits as part of outpatient costs, while Li et al.Citation10 split outpatient costs into several categories, depending on the type of visit). While we are not aware of any previous estimates of the costs of NPSLE in the US, a survey-based study from Hong Kong found that SLE subjects with neuropsychiatric complications had annual costs of $12,316Citation1Citation5. This estimate is lower than annual cost estimates for NPSLE in the present study, but this could be due to differences in country-specific health systems, reimbursement processes, and inclusion criteria.

Limitations related to claims data should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Importantly, the algorithm used to identify lupus nephritis and NPSLE patients in this study was not based on clinical evaluation. The presence of a diagnosis code on a medical claim could either indicate presence of the disease or it could be a marker for a rule-out criterion (rather than actual disease). For an individual to be included in this study, a medical claim with a diagnosis of SLE was required; in addition, a medical claim with a diagnosis for nephritis and/or neuropsychiatric involvement was required for study inclusion. In order to make the study more generalizable and broadly select as many lupus nephritis and NPSLE subjects as possible, there were no time constraints put on the relationship between the service date of the qualifying SLE claim and the service date(s) of the qualifying nephritis and/or neuropsychiatric claims (other than the requirement that all service dates be between 2003–2008). This approach was employed to better reflect how subjects may be diagnosed in a real word setting, as some subjects may first receive a nephritis or NP diagnosis, and only later be diagnosed with lupus. Although it is possible that some subjects who were selected for the study had an earlier claim for nephritis or a neuropsychiatric condition (e.g., in 2003) that was medically unrelated to a later claim for SLE (e.g., in 2007), we note that the majority of patients (∼79% lupus nephritis and 85% NPSLE) had the diagnosis/procedure of the nephritis and neuropsychiatric condition within one calendar year of the SLE index date (suggesting that the renal or NP involvement was likely related to SLE). Also, information on disease stage and severity is difficult to determine with claims data. Future research in which subjects’ medical charts are reviewed could help validate the claims-based patient identification algorithm used here, and also help establish the severity and/or chronicity of disease. A previous study demonstrated that a claims-based algorithm could identify lupus nephritis subjects from Medicaid billing databases with a positive predictive value of 80%Citation18; this algorithm was similar to what we used in the present study. Also, costs in this study may be under-estimated if some very sick individuals with lupus nephritis and/or NPSLE are no longer working, and are instead enrolled in a public health plan or receive charity care. The findings from this study are most applicable to understanding disease costs in a managed care population, and the findings here may not be generalizable to other populations.

A number of topics would be of interest to investigate in future studies. As incident patients may have more active disease which requires aggressive diagnosis and management, future research should investigate healthcare costs and resource use in incident populations of lupus nephritis and NPSLE subjects. Indirect costs (such as costs due to lost time at work) also contribute to the economic burden associated with lupus nephritis and/or NPSLE, but these were not evaluated in our study. We did not collect information on how many subjects (if any) were on capitated plans, and the influence of capitation on costs among subjects with lupus nephritis and/or NPSLE could be evaluated in future studies. Finally, future research should investigate in depth the healthcare costs and resource use associated with other SLE-related complications, such as cardiovascular disease.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that subjects with lupus nephritis or NPSLE had high costs and resource use (as compared to unaffected control subjects) in this retrospective claims-based analysis of a managed care population. Future research needs to focus on preventing progression to these complications, as well as the development of new treatment strategies for lupus nephritis and NPSLE, which can improve outcomes while decreasing medical costs.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by MedImmune, LLC.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

DEF has received grant/research support from Abbott, Actelion, Amgen, BMS, Gilead, GSK, NIH, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, UCB; has served as a medical advisory board member to MedImmune, LLC; has served as a consultant to Abbott, Actelion, Amgen, BMS, BiogenIdec, Centocor, CORRONA, Gilead, GSK, NIH, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, UCB; has served on Speakers Bureaus for Abbott, Actelion, UCB (CME only); and has received Honoraria from Abbott, Actelion, Amgen, BMS, BiogenIdec, Centocor, Gilead, NIH, Roche/Genentech. WG, KG, and AWF are full-time employees of MedImmune, LLC. AEC has served as a consultant to MedImmune, LLC, Bristol Myers Squibb, and GlaxoSmithKline/Human Genome Sciences and has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline/Human Genome Sciences. TB and SRI have served as consultants to MedImmune LLC as employees of OptumInsight.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (40.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jesse Potash, PhD, at OptumInsight for assistance with preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Manson JJ, Isenberg DA. The pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Neth J Med 2003;61:343-6

- Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1982;25:1271-7

- Manson JJ, Rahman A. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2006;1:6

- Moss KE, Ioannou Y, Sultan SM, et al. Outcome of a cohort of 300 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus attending a dedicated clinic for over two decades. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:409-13

- Panopalis P, Clarke AE. Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical manifestations, treatment and economics. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2006;6:563-75

- Francis L, Perl A. Pharmacotherapy of systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2009;10:1481-94

- The American College of Rheumatology nomenclature and case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:599-608

- Bertsias GK, Salmon JE, Boumpas DT. Therapeutic opportunities in systemic lupus erythematosus: state of the art and prospects for the new decade. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1603-11

- Furst DE, Clarke AE, Fernandes AW, et al. Resource utilization and direct medical costs in adult systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients from a commercially insured population. Lupus 2013; (Jan 22 Epub ahead of print)

- Li T, Carls GS, Panopalis P, et al. Long-term medical costs and resource utilization in systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis: a five-year analysis of a large medicaid population. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:755-63

- Pelletier EM, Ogale S, Yu E, et al. Economic outcomes in patients diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus with versus without nephritis: results from an analysis of data from a US claims database. Clin Ther 2009;31:2653-64

- Carls G, Li T, Panopalis P, et al. Direct and indirect costs to employers of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with and without nephritis. J Occup Environ Med 2009;51:66-79

- Clarke AE, Panopalis P, Petri M, et al. SLE patients with renal damage incur higher health care costs. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:329-33

- Aghdassi E, Zhang W, St-Pierre Y, et al. Healthcare cost and loss of productivity in a Canadian population of patients with and without lupus nephritis. J Rheumatol 2011;38:658-66

- Zhu TY, Tam LS, Lee VW, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus with neuropsychiatric manifestation incurs high disease costs: a cost-of-illness study in Hong Kong. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:564-8

- Chastek BJ, Oleen-Burkey M, Lopez-Bresnahan MV. Medical chart validation of an algorithm for identifying multiple sclerosis relapse in healthcare claims. J Med Econ 2010;13:618-25

- Rector TS, Wickstrom SL, Shah M, et al. Specificity and sensitivity of claims-based algorithms for identifying members of Medicare+Choice health plans that have chronic medical conditions. Health Serv Res 2004;39:1839-57

- Chibnik LB, Massarotti EM, Costenbader KH. Identification and validation of lupus nephritis cases using administrative data. Lupus 2010;19:741-3

- Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, et al. Derivation of the SLEDAI: a disease activity index for lupus patients. Arthritis Rheum 1992;35:630-40

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Medical Care 2005;43:1130-9

- Altman D, Cutler D, Zeckhauser R. Enrollee mix, treatment intensity, and cost in competing indemnity and HMO plans. J Health Econ 2003;22:23-45