Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a percutaneous procedure that allows introducing an aortic valve prosthesis without the need for open heart surgery. The technique is used mainly in elderly patients who are considered at very high risk of dying due to the operation or with contra-indications for surgical treatment. If patients with a symptomatic aortic stenosis are left untreated, the prognosis is bleak, and most of them will die within 5 yearsCitation1. TAVI is mostly accomplished via a femoral, or less often via a subclavian, artery. Patients with no adequate trans-arterial access route can be treated via the trans-apical approach in which the prosthesis is inserted from the apex of the heart via a mini-thoracotomy.

In Europe, the pre-market regulation system for medical devices is based on the demonstration of safety and performance of a given device. In the case of TAVI, although no single randomized controlled trial (RCT) was performed, TAVI was applied in tens of thousands of patients. In contrast, the US system requires the pre-market demonstration of safety and efficacy/effectiveness. For demonstration of the latter, an RCT is essentialCitation2. As a result, the PARTNER (Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve) trial was performed. The study allocated patients with severe aortic stenosis who were considered not good candidates for surgical aortic valve replacement in two separate sub-studies: those at very high risk for surgeryCitation3, and those deemed inoperableCitation4. After 1 year, high-risk operable patients were no better off with TAVI than with surgical aortic valve replacement. Inoperable patients had a 20% absolute reduction in 1 year mortality ().

Table 1. Unpublished results related to the PARTNER trial (inoperable patients).

This was great news, and it is no surprise that economic evaluations calculating the intervention’s cost-effectiveness followed suit. An Edwards-sponsored economic evaluation is published in this edition of Journal of Medical EconomicsCitation5. The analysis is based on the results of the PARTNER trial for inoperable patients. However, a rigorous analysis of all available data in combination with a study of real-world TAVI practice in Europe made us conclude that the arguments supporting the widespread use of TAVI do not stand up to scrutinyCitation6,Citation7. In addition, the PARTNER trial seems to suffer from significant problems with publication bias, lack of data transparency, and unbalanced patient characteristics between the trial’s treatment arms. This means that the published effect size of TAVI, and economic evaluations relying on it, might be over-optimistic. The lack of evidence for the transapical TAVI procedure, higher 30-day mortality rates in daily practice, and the often subjective difference between high-risk and inoperable patients also deserves further attention.

A critical assessment of the PARTNER trial

Publication bias

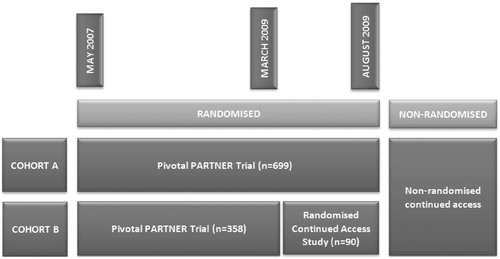

In March 2009, coincident with completion of enrolment into Cohort B (inoperable patients), the FDA authorized the PARTNER trial investigators to begin a ‘Continued Access Study’. At the onset, the protocol was the same as the pivotal PARTNER study until August 2009, when Cohort A (high-risk operable patients) enrolment was completed (). In the Continued Access Study, 41 patients were randomized to TAVI and 49 to standard care. So far, the results of this randomized Continued Access Study have not been published and, to our knowledge, never been presented at a scientific meeting. Some results were presented at the July 20, 2011 FDA meeting and, unexpectedly, in contrast to the results from the pivotal trial, TAVI treated patients fared worse than those following standard treatment ()Citation8. Mortality of TAVI patients after 1 year was an absolute 12.7% higher than in the control group. It is difficult to understand that the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), being aware of this negative trial through our correspondence, publishes 2-year follow-up results of the pivotal trials without demanding the study sponsor publish or discuss this negative randomized follow-up trial. We also tried to obtain data through the FDA. The Agency let us know that any further data analyses of a pre-market application is proprietary information, therefore we were told it was up to the sponsor to release this information. In answer to our request, the study sponsor was unwilling to reveal full details of this randomized Continued Access Study. In our view, this behaviour is both ethically and scientifically unacceptable and should be legally regulated in the future. Making a non-published negative trial public is the task of the study sponsor. Policy-makers should have full access to trial data in order to make rational and balanced decisions.

Unbalanced patient characteristics

In contrast to what is mentioned in the original publication of the PARTNER trial and the economic evaluation, baseline characteristics of the patients in the intervention and control groups were unbalanced in favour of the TAVI group. According to the study protocol, patients were considered inoperable when two heart surgeons decided that they could not be operated on. Two sub-groups of those patients were distinguished: those who were inoperable for anatomical reasons, and those who were inoperable for medical reasons. The latter group with high co-morbidities are more prevalent in the control group, and more anatomic inoperable patients are included in the TAVI group (see ). Anatomic inoperable patients may be expected to benefit most from a successful TAVI since their life expectancy and quality-of-life are less hampered by other conditions. Data published in 2012 suggest that the mortality benefit after TAVI may be limited to patients who do not have extensive co-existing conditionsCitation9. All these imbalances might result from a play of chance, but they may as well have been due to a flawed randomization. The unbalance in patient characteristics in the PARTNER trial over-optimistically influence both short- and long-term results.

Table 2. Selection of patient characteristics in the PARTNER trial (inoperable patients).

Trans-apical TAVI

There are two variants of the TAVI procedure. In the first, the artificial valve is inserted through an artery, generally the femoral artery, in which case it is called a ‘transfemoral TAVI’. If, however, due to significant atheromatosis, neither of the two femoral arteries is patent, a TAVI can also be performed directly through the thoracic wall and the apex of the heart. This variant is called a ‘transapical TAVI’. The efficacy of the latter approach, that can hardly be named non-invasive, cannot be clearly derived from the PARTNER trial. In patients at high surgical risk, a sub-group analysis suggests that the trans-apical approach is not inferior to surgery, but doubles the stroke risk. Although the FDA proposed to do so, the PARTNER study sponsor declined to include a trans-apical arm in inoperable patientsCitation10. Nevertheless, in Europe, the CE labelled device is widely used with this approach. For example, from the UK TAVI Registry, it appears that 409 out of 1620 TAVI patients (25%) are treated trans-apically with a 1-year survival rate of 74.5%Citation11. In an update of the FRANCE-2 Registry reporting on 2430 patients treated in 2010 and 2011, 20% underwent trans-apical TAVI with a 6-month survival rate of 79.8%Citation12. Being a general limitation of registries, it is not known what those patients’ survival would have been had they been treated medically or by standard surgery.

Very recently, the results from the STACCATO trial, an independent randomized controlled trial of trans-apical TAVI in operable elderly patients, have been presentedCitation13. The primary end-point (30-day all cause mortality, major stroke, and/or renal failure) was reached in 5/34 TAVI and 1/36 surgically-treated patients, and the study was prematurely terminated because of safety reasons after advice from the Data Safety Monitoring Board.

The non-evidence-based widespread use of trans-apical TAVI in Europe is of major concern. It is very probable that both decision-makers and eligible patients are not aware of the poor effectiveness and safety issues of this approach. Based on current knowledge, it should only be used in a randomized controlled setting. These observations once more put into question the appropriateness for the European regulatory system granting the trans-apical Sapien valve a CE label in 2007Citation6,Citation14. The pre-market clinical evaluation for high-risk devices should become more solid.

30-day mortality

The economic evaluation mentions that it is reasonable to assume that, with time, as physicians become more familiar with the TAVI procedure, associated outcomes may further improve. On the other hand, we have to take care about possible differences between trial- and real-world settings. Are the excellent results reported by the PARTNER investigators reproducible in real world conditions? 30-day overall mortality after trans-femoral TAVI in the PARTNER trial was the lowest ever reported in medical literature: in high-risk operable patients, as-treated mortality was 3.7%. In inoperable patients it was 6.4%. The combined mortality from both cohorts was 4.8%. Observational data suggest that currently it is hard to copy the excellent results obtained in the PARTNER trial. Experienced French heart teams using newer and reportedly better-performing versions of the Sapien valve, both in high-risk and in inoperable patients (n = 810), reported a 30-day mortality following trans-femoral TAVI of 7.8%Citation12. The NICE guidance refers to a European register with a 30-day mortality rate of 9% (88/1038)Citation15. This contrast is remarkable, given the fact that most of the participating US centres in the PARTNER trial had no previous experience with TAVI. The importance of technical skills and the presence of a learning curve is stressed by most authors in the fieldCitation16. Furthermore, in the PARTNER trial an earlier larger bore model of the Edwards Sapien device was used. This is supposed to be accompanied by a higher rate of vascular complications as compared to newer and smaller size devices currently used in Europe. Further research is needed to find out what the causes are for these differences.

Differentiation of high-risk vs inoperable patients

Based on current evidence, reimbursing TAVI should not be recommended in high-risk operable patients: TAVI and surgery are associated with similar mortality rates at 1 year, produce similar improvements in cardiac symptoms, but there is a twice as high rate of stroke after TAVI as compared to surgery and, based on Belgian real-world cost data, the TAVI procedure is much more expensiveCitation6,Citation14,Citation17. Therefore, it is hard to defend a reimbursement for TAVI in high-risk operable patients as an efficient use of limited resources. For inoperable patients, this depends on the type of inoperable patients (see further) and the willingness and ability to pay for the procedure.

Although one would expect from the trial inclusion criteria more severe co-morbid conditions in inoperable patients of the PARTNER trial, most of the registered co-morbidities were equally represented in the two cohorts. With the exception of anatomical prohibitive conditions, the clinical differentiation of PARTNER high-risk operable from inoperable patients is essentially based on the subjective clinical feeling of the physicians involved (see )Citation6. The subjective labelling of operable patients as inoperable should not be neglected by policy-makers. In the German registry, many patients were less sick than those enrolled in either cohort of the PARTNER trialCitation18. In the past, Belgian patients also seemed on average to be less sick than those treated in any of the PARTNER trial cohortsCitation6. Besides the waste of limited resources, many of these European patients might have been better off with standard surgery.

Table 3. PARTNER trial baseline characteristics.

Anatomically vs medically inoperable patients

Published results of the PARTNER trial were much better for inoperable patients than for high-risk operables. Nevertheless, the intervention remains relatively expensive because of the currently high device cost, especially if the results of the negative Continued Access Trial are taken into consideration. However, the anatomic inoperable patients seem to benefit most from TAVI. In the pivotal PARTNER trial, mortality reduction after TAVI in patients with anatomically prohibitive conditions was 27.9% at 1 year, as compared to 17.0% in patients with severe medical co-morbidities (see ). Results from this specific sub-group of patients were not available from the negative Continued Access Study because of the refusal to reveal this information. If policy-makers are willing to pay the relatively high price for TAVI, based on medico-economic arguments, they might give priority to focus on the anatomically inoperable patientsCitation17. As discussed above, these patients can objectively be distinguished from other patient groups.

Conclusion

Critical appraisal of the pivotal PARTNER trial results, in combination with the negative data from the Continued Access Study, and the early discontinuation of the STACCATO trial, lead us conclude that the published effect size of TAVI might be over-optimistic and hard to copy in real world clinical practice. Furthermore, it is hard to accept that crucial data on the negative Continued Access Study and medically relevant patient sub-groups remain unpublished more than 1 year after the pivotal trial appeared in a leading medical journal.

HTA agencies in Europe are often confronted by a lack of high-quality clinical evidence when evaluating novel high-risk devices. It has been shown that this is linked to the European regulatory system that allows early market introduction based on limited clinical data. Europe should require high-quality randomized trials demonstrating clinical efficacy and safety prior to granting the marketing approval of innovative high-risk medical devices. In order to allow physicians to practice evidence-based medicine, patients to make an informed decision, and HTA agencies to produce the correct assessment, a major improvement in the transparency of information is also needed for such devices in EuropeCitation2.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This paper was not funded.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Varadarajan P, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, et al. Survival in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis is dramatically improved by aortic valve replacement: results from a cohort of 277 patients aged > or = 80 years. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;30:722-7

- Hulstaert F, Neyt M, Vinck I, et al. Pre-market clinical evaluations of innovative high-risk medical devices in Europe. Int J Technol Assess Health Care (accepted for publication) 2012;28:278-84

- Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2187-98

- Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1597-607

- Hancock-Howard R, Feindel C, Rodes-Cabau J, et al. Transfemoral aortic valve replacement versus medical management in high risk patients with symptomatic aortic valve stenosis: Canadian cost-effectivenessanalysis based on the PARTNER trial cohort B findings. J Med Econ; 16. (Published Online February 6, 2013.)

- Neyt M, Van Brabandt H, Van de Sande S, et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI): a health technology assessment update. KCE Reports. Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE), 2011

- Van Brabandt H, Neyt M, Hulstaert F. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI): risky and costly. BMJ 2012;345:e4710

- FDA. SAPIEN® THV Briefing Document – Advisory Committee Meeting. FDA, 2011. p 301. Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/MedicalDevices/MedicalDevicesAdvisoryCommittee/CirculatorySystemDevicesPanel/UCM262935.pdf. [Last accessed 12 February 2013].

- Makkar RR, Fontana GP, Jilaihawi H, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement for inoperable severe aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2012;preprint1696-704

- FDA. FDA Executive summary: Edwards SAPIEN THV. FDA, 2011. Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/MedicalDevices/MedicalDevicesAdvisoryCommittee/CirculatorySystemDevicesPanel/UCM262930.pdf. [Last accessed 12 February 2013].

- Blackman D, PCR LondonValves, editor. UK TAVI Registry. Outcome of TAVI by valve type and access route. London, 2011. Available at http://www.pcronline.com/Lectures/2011/Outcome-of-TAVI-by-valve-type-and-access-route.-UK-TAVI-registry. [Last accessed 12 February 2013]

- Gilard M. FRANCE II - FRench Aortic National CoreValve and Edwards registry. EuroPCR2011. Paris, 2011

- Thuesen L. A prospective, randomized trial of transapical transcatheter aortic valve implantation vs. surgical aortic valve replacement in operable elderly patients with aortic stenosis. The STACCATO Trial. TCT congress 2011 November 10, 2011; San Francisco, CA

- Van Brabandt H, Neyt M. Percutaneous heart valve implantation in congenital and degenerative valve disease. A rapid Health Technology Assessment. KCE Reports. Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE), 2008

- NICE. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for aortic stenosis. NICE interventional procedure guidance 421. London: NICE, 2012

- Alli OO, Booker JD, Lennon RJ, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: assessing the learning curve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:72-9

- Neyt M, Van Brabandt H, Devriese S, et al. A cost-utility analysis of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Belgium: focusing on a well-defined and identifiable population. BMJ Open 2012;2:1-8. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001032

- Mohr F. The German aortic valve registry. 40th Annual Meeting of the German Society for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery; 2011; Stuttgart