Abstract

Objective:

To quantify the differences in hospital length of stay (LOS) and cost between healthy and vulnerable children with cystic fibrosis (CF), insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), cancer, and epilepsy who contract rotavirus (RVGE) or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

Methods:

Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data were collected for England, for children <5 years old, admitted between April 2001 and March 2008, using ICD-10 codes for RVGE and RSV. Cases were identified as having RVGE and/or RSV plus CF, IDDM, cancer, or epilepsy. Healthy controls had RVGE and/or RSV only, additional controls had eczema only. Cost, hospital LOS, and demographics were collected.

Results:

Four hundred and eighty-six (0.5%) cases and 101,784 (99.5%) healthy controls were admitted with RVGE or RSV, with 17,420 eczema controls. RVGE was present in 153 (31.5%) cases and 7532 (7.4%) healthy controls, and RSV in 333 (68.5%) cases and 94,252 (92.6%) healthy controls. Cases were older (1.1 years, SD = 1.3 years), had greater LOS (9.9 days, SD = 19.9), and cost more (£3477, SD = £7765) than healthy controls (age = 0.2, SD = 0.5, p < 0.001; LOS = 1.9 days, SD = 3.1, p < 0.001; cost = £595, SD = £727, p < 0.001). Cost for cases was 6-times greater than healthy controls (p < 0.001). Controls had a 0.3 day greater LOS (p < 0.001) with RSV, but a £17 (p = 0.085) lower mean cost than RVGE.

Conclusion:

RVGE and RSV are more serious diseases in vulnerable children, requiring more intense resource use. The importance of preventing infection in vulnerable children is underlined by hygiene and appropriate isolation and vaccination strategies. When universal vaccination is under consideration, as for rotavirus vaccines, evaluation of a vaccination programme should consider the potentially positive impact on vulnerable children.

Limitations:

Limitations of the study include a dependency on accurate coding, an expectation that patients are identified through laboratory testing, and the possibility of unidentified underlying conditions affecting the burden.

Introduction

The UK Government is currently attempting some of the biggest reforms to the NHS since its foundation, demanding £15–£20 billion of efficiency savings, with acute medical services being a key area of change and increased efficiencyCitation1. Government policy has placed a strong focus on reducing pressures from avoidable illnesses to allow the NHS to focus its efforts on other prioritiesCitation2. Paediatric acute medical care is dominated by winter epidemics of bronchiolitis and gastroenteritis (late winter and early spring). Understanding where disease burden falls unequally upon different patient groups helps aid planning, informs clinical practice, and highlights where potential savings could be made through disease prevention.

In the UK, sharp peaks in patient numbers require acute medical services via avenues of unscheduled care (via primary healthcare, walk-in centres, and a large proportion via Emergency Departments). The main infections causing these surges in patient numbers are rotavirus (RVGE) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)Citation3–5, even though efficacious vaccinations, such as RV1 and RV5 for RVGE, exist. Treatment for both these infections is largely supportive (oxygen, fluids, nutritional support, and intensive care for a few of the most severe cases). Although the treatment is largely conservative, frequently the most complicated problem is finding an isolation cubicle to prevent cross-infection and nosocomial transmission to others in patients. Winter bed problems in paediatrics translate to a shortage of isolation cubicles and many units have to resort to isolating children that are commonly infected with RSV so as to increase the efficiency of resources; however, this is known to increase the risk of cross-infection with other winter virusesCitation6. It is not known how children with impaired respiratory health or impaired immunity may respond differently to these common infections in terms of length of stay (LOS) or cost, or even as a comparator with healthy control children in the 21st century.

With regards to RSV, risk factors have only been considered in the under 2 year olds and include prematurityCitation7, lack of breast milkCitation8, previous apnoeas, and other respiratory diseasesCitation8,Citation9. With respect to RVGE, risk factors are less clearly defined and collected from relatively small scale case series without a control group comparison to estimate the contribution of the co-morbidityCitation10, but are likely to include malabsorbtion, malnutrition, immune deficiencyCitation10, and cancerCitation11,Citation12. There are no data on whether type I diabetes is associated with increased hospital admission duration in either RSV or RVGE. Type I diabetes is a common serious co-morbidity with loss of diabetic control as a consequence.

This study has used national admission data from the whole of England over a 7 year period in order to enable a robust, but focused study to measure the size of the effect, in numbers, hospital length of stay, and healthcare cost, between vulnerable child groups with RVGE and RSV and compare them with healthy controls and other chronic illness groups. Identifying vulnerable groups of children will enable front line clinical staff to plan ahead for complications such as prolonged stay at an early stage, but will also highlight the complexity of care some children require to overcome even common illnesses.

This study aims to compare the healthcare associated costs and differences in hospital admission duration for rotavirus (RVGE) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections in children with co-morbidities (cancer, type 1 diabetes, cystic fibrosis, and epilepsy) compared to children admitted without co-morbidities and complications (healthy controls) and a further control group of RSV/RVGE free children admitted with chronic eczema. Cancer, type 1 diabetes, cystic fibrosis, and epilepsy were selected as non-infectious diseases which would not require specific infection control methods in their management but which represent diseases where childrens’ prognosis could be significantly affected by an infectious co-morbidity. Chronic eczema was selected as a control group because its dermatological presentation enables clarity of differential diagnosis from RSV and RVGE and, therefore, provides an additional comparator.

Methods

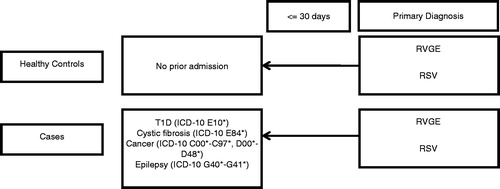

Data were obtained from the Health Episode Statistics (HES) database for the period 1 April 2001 to 31 March 2008, where patients, aged under 5 years, were admitted to hospital in England with a primary diagnosis of rotavirus gastroenteritis (RVGE) (ICD-10 A08.0) or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (ICD-10 B97.4, J12*, J21*) ().

Patients were then categorized into three groups:

Healthy controls: a primary diagnosis of RVGE or RSV, with no secondary diagnoses and no hospital admissions within the previous 30 days.

Eczema controls: a primary diagnosis of eczema with no other co-morbidities, enabling the comparison of admissions from infectious and non-infectious causes.

Cases (vulnerable children): admission with RVGE or RSV within 30 days of a prior admission with a primary diagnosis of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (T1D) (ICD-10 E10*), cystic fibrosis (ICD-10 E84*), cancer (ICD-10 C00* to C97*, D00* to D48*), or epilepsy (ICD-10 G40* to G41*).

Healthy controls: multiple diagnoses, re-admission within 30 days of a prior admission.

Eczema controls: any secondary diagnosis code for T1D, cystic fibrosis, cancer, or epilepsy.

Cases (vulnerable children): any re-admission between case admission and admission with RVGE or RSV, with a primary diagnosis of any non-T1D, cystic fibrosis, cancer, or epilepsy code; re-admission with RVGE or RSV greater than 30 days following an admission with T1D, cystic fibrosis, cancer, or epilepsy.

Any readmission with RVGE or RSV within 30 days of a previous admission with RVGE or RSV.

Data were provided as finished consultant episodes (FCEs), where a patient’s care can be transferred from one consultant to another, even within the same hospital, representing a new episode. For this study, episodes were aggregated into unique admissions.

Relative risk was calculated to identify whether patients admitted or re-admitted with RVGE were more likely to be vulnerable children than those admitted or re-admitted with RSV.

The cost of the admission was calculated using National Health Service (NHS) Healthcare Resource Groups (HRGs) processed through HRG 3.5 grouper. HRGs were designed to group treatment episodes, based on the patient’s primary and secondary procedures (OPCS-4 procedure codes), primary and secondary diagnoses (ICD-10 codes), age, sex, method of discharge, and length of stay, into units that are similar in both clinical relevance and resource use. The dominant HRG was assigned to each admission, and the costs were mapped to each unique admission using the NHS reference costs for 2007/08.

Statistical analysis was undertaken using SPSS PASW statistics software version 18.

Results

There were a total of 102,270 patients, admitted to hospital with a primary diagnosis of RVGE or RSV. Of these patients 101,784 (99.5%) were categorized as healthy controls, and 486 (0.5%) as cases (vulnerable children) (). There were also 17,420 eczema controls.

Table 1. Mean age, hospital length of stay, and cost of stay by patient group.

Of the 486 cases, 153 (31.5%) were re-admitted with RVGE and 333 (68.5%) with RSV, while in the healthy controls, 7532 (7.4%) were admitted with RVGE and 94,252 (92.6%) were admitted with RSV. Furthermore, it could be seen that those admitted or re-admitted with RVGE were 5.7-times (95% CI = 4.7–6.8; p < 0.05) more likely to be vulnerable children than those admitted with RSV.

Of the cases readmitted with rotavirus, mean age was 1.4 years (SD = 1.3), mean LOS was 9.3 days (SD = 12.4), and mean cost was £3418 (SD = £4877), while in those readmitted with RSV mean age was 1.0 years (SD = 1.3), mean LOS was 10.1 days (SD = 22.5), and mean cost was £3506 (SD = 8834).

Analysis showed that the difference in mean values for age (0.9 years) and hospital LOS (0.2 days) were statistically significant between the healthy controls and the eczema controls groups (p < 0.001), although the difference in cost (£5) was not significant (p = 0.584). Between the healthy controls and the cases, the differences between all three variables, age (0.9 years), LOS (8.0 days), and cost (£2,882) were significant (p < 0.001), while between the eczema control and case groups LOS (8.2 days) and cost (£2,887) were significantly different (p < 0.001), while no difference was observed in mean age (0.0 years) (p = 0.433). The eczema control group and the case group were the eldest, while the case group were admitted for longest and accrued most cost.

Hospital length of stay

Univariate linear regression analysis showed that, when adjusted for age, sex, and hospital admission method (either referred via a GP or a self-referral via an emergency department), the mean hospital LOS within the cases group was 8.9 days, while for healthy controls the LOS was 4.5-times lower at 2.0 days (p < 0.001), and in the eczema controls LOS was 4.9-times lower at 1.8 days (p < 0.001) (). For each year of age of the patient the LOS reduced by 0.06 days (p < 0.001), while LOS for males was 0.2 days less than for females (p < 0.001), and for those admitted having been referred via a GP, LOS was 0.3 days less than those self-referred via an emergency department (p < 0.001).

Table 2. Univariate linear regression model analysing the length of stay of the hospital admission between patient groups.

Cost

Further regression models showed that, by adjusting for sex, admission method, and hospital LOS, the mean cost of a patient within the cases group was £533, while for healthy controls the cost was 6.3-times lower at £84 (p < 0.001), and in the eczema controls 6.6-times lower at £81 (p < 0.001) (). For males the cost was £8 less than for females (p < 0.001), while those referred via a GP cost £605 (p < 0.001) more than those admitted as a self-referral. Hospital LOS contributed £280 (p < 0.001) per day to the overall cost.

Table 3. Univariate linear regression model analysing the cost of hospital admission between patient groups.

Comparing the infection types within each group, it could be seen that both LOS and cost were significantly different in healthy controls with LOS of 0.3 days longer in patients with RSV than in patients with RVGE (p < 0.001) (). Conversely, mean cost was £107 lower in patients with RSV than patients with RVGE (p = 0.001), although with cost significantly increasing by £704 in GP referrals compared to self-referrals (). It is possible that those admitted to hospital via primary care (GP referral) select out the more serious cases. This could indicate why the cost for GP-referred admissions is significantly higher than for admissions than parent self-referral to emergency departments.

Table 4. Univariate linear regression model analysing the length of stay of the hospital admission between infection types in controls (healthy children).

Table 5. Univariate linear regression model analysing the cost of the hospital admission between infection types in controls (healthy children).

In the cases there was no significant difference in LOS (p = 0.764) () or cost (p = 0.431) () between patients with RVGE and RSV, with LOS a significant driver of cost (p < 0.001) adding £374 per day of LOS.

Table 6. Univariate linear regression model analysing the length of stay of the hospital admission between infection types in cases.

Table 7. Univariate linear regression model analysing the cost of the hospital admission between infection types in cases.

Discussion

This case control study shows that, although the majority of RVGE and RSV admissions are in healthy children, it is a substantially more serious disease in children admitted with co-morbidities than those without. This burden, quantified by hospital length of stay and cost, has a significant impact on the NHS, with LOS being 5.2-times (p < 0.001) and cost being 5.8-times (p < 0.001) greater in vulnerable children than those without co-morbidities or complications. It should be noted that the cost per case when corrected for the substantially greater LOS seen in the vulnerable children still showed a 6-fold greater daily cost (p < 0.001). This matches expectations from clinical experience that, when children with associated respiratory, immune problems, or other serious diseases contract a winter virus, such as RSV or seasonal RVGE, the course of the illness is much more serious, with greater requirement for interventional treatment and monitoring due to worse nutritionCitation13 and damaged immune responseCitation14.

This study has shown that, in children without co-morbidities or complications, admissions with RSV are longer than for those with RVGE (p < 0.001), while costs are reversed, with RVGE admissions costing more than RSV admissions (p < 0.001). It is possible, however, that, although statistically significant, due to the large number of patients the difference observed is not clinically significant. In the vulnerable children, however, no significant difference in LOS (p = 0.764) or cost (p = 0.431) was observed between those with RVGE and those with RSV.

Savings, in terms of both LOS and cost, could be made by preventing vulnerable children from developing both RVGE and RSV. Although this study measures and demonstrates a very different clinical picture between vulnerable children and controls in terms of cost and length of stay, this is only a proxy measure for significant illness and suffering that is not directly measured. This should further drive standards of hygiene and open up consideration of other strategies of disease prevention such as vaccination. Prevention of RVGE and RSV is imperative in vulnerable children both in the context of correct isolation techniques to reduce the risk of nosocomial infection and simple hygiene to reduce cross-infection in a primary care setting.

Conclusion

This study underlines a practical clinical scenario that is very familiar, namely that not all children are the same as per the standard cohort and that vulnerable children in particular often require special consideration due to their clinical needs.

Where economic models for vaccines tend to look at whole cohorts it is important that clinically relevant sub-groups of children should be taken into consideration. Where the introduction of universal vaccination is under consideration, as in the case of rotavirus vaccines, evaluation of a vaccination programme should consider the potentially positive impact of indirect protection on vulnerable children.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations associated with the study design. The analysis is dependent upon the accuracy of coding/data entry within HES, which may not be entered uniformly at all hospitals. It is possible that patients with RVGE or RSV are not identified, as laboratory testing and identification is not conducted, and that they are coded as having another virus instead. It should also be noted that healthy controls need only to have not been admitted to hospital within the last 30 days, it is possible that these patients may have an underlying disease which did not require admission in this period, but may still have the effect of increasing the burden within the group.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Sanofi Pasteur MSD, of whom employees helped in the design and undertaking of the study and the writing of the manuscript.

Declaration of financial relationships

NA, SC, and FR are employees of Sanofi Pasteur MSD, RDP and DC acted as consultants to Sanofi Pasteur MSD. DC has attended two advisory board meetings for SPMSD, and is involved with an investigator initiated research grant, for an unrelated study, held by Sheffield Children’s Hospital. No other conflicts of interest exist.

References

- Department of Health. Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS. London: DH. 2010. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_117794.pdf. Accessed February 2012

- Department of Health. Healthy Lives, Healthy People: our strategy for public health in England. London: DH. 2010. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_127424.pdf. Accessed February 2012

- Waters V, Ford-Jones EL, Petric M, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pediatric viral diarrhea: a prospective longitudinal study in hospitals, emergency departments, pediatric practices and child care centers during the winter rotavirus outbreak, 1997 to 1998. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19:843-8

- Muller-Pebody B, Edmunds WJ, Zambon MC, et al. Contribution of RSV to bronchiolitis and pneumonia associated hospitalizations in English children, April 1995–March 1998. Epidemiol Infect 2002;129:99-106

- Shay DK, Holman RC, Newman RD, et al. Bronchiolitis-associated hospitalizations among US children, 1980–1996. JAMA 1999;282:1440-6

- Madge P, Paton JY, McColl JH, et al. Prospective controlled study of four infection-control procedures to prevent nosocomial infection with respiratory syncytial virus. The Lancet 1992;340:1079-83

- Roeckl-Wiedmann I, Liese JG, Grill E, et al. Economic evaluation of possible prevention of RSV-related hospitalizations in premature infants in Germany. Eur J Pediatr 2003;162:237-44

- Wang EEL, Law BJ, Stephens D. Pediatric Investigators Collaborative Network on Infections in Canada (PICNIC) prospective study of risk factors and outcomes in patients hospitalized with respiratory syncytial viral lower respiratory tract infection. J Pediatr 1995;126:212-9

- Holberg CJ, Wright AL, Martinez FD, et al. Risk factors for respiratory syncytial virus-associated lower respiratory illnesses in the first year of life. Am J Epidemiol 1991;133:1135-51

- Huppertz H-I, Salman N, Giaquinto C. Risk factors for severe rotavirus gastroenteritis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008;27:s11-19

- Rogers M, Weinstock DM, Eagan J, et al. Rotavirus outbreak on a pediatric oncology floor: Possible association with toys. Am J Infect Control 2000;28:378-80

- Rayani A, Bode U, Habas E, et al. Rotavirus infections in paediatric oncology patients: A matched-pairs analysis. Scand Journal Gastroenterol 2007;42:81-7

- Pelletier DL, Frongillo Jr EA, Schroeder DG, et al. The effects of malnutrition on child mortality in developing countries. Bull World Health Org 1995;73:443-8

- Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, et al. Consensus statement. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring Project. JAMA 1999;282:677-86