Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of posaconazole vs itraconazole in the prevention of invasive fungal infections (IFIs) in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT).

Methods:

Total hospital-based costs from initial admission for allo-HSCT until day 100 after transplantation were evaluated for 49 patients in whom the clinical efficacy of antifungal prophylaxis with posaconazole vs itraconazole had been previously analyzed and reported. Clinical and economic data were used to determine the incremental costs per IFI avoided and per life-year gained for posaconazole compared with itraconazole. Confidence intervals for the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) and a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve were estimated through bootstrapping with the bias-corrected percentile method.

Results:

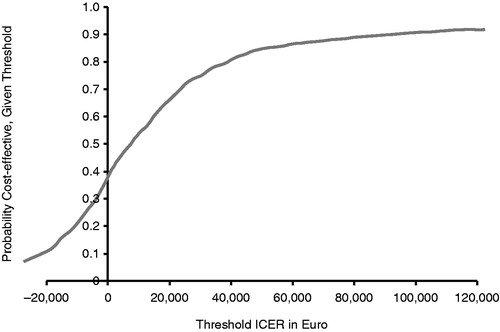

According to our analysis, the total cost of allo-HSCT per patient during the 100-day fixed-treatment period was €46,562 in the posaconazole group (n = 33) and €45,080 in the itraconazole group (n = 16). However, the reduction in the incidence of IFI and the improved outcome with posaconazole resulted in a favorable ICER of €11,856 per IFI avoided and €5218 per life-year gained. With the outcomes of the bootstrap procedure, the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve was constructed. Assuming a threshold of €30,000 per life-year gained, the ICER based on life-years gained is acceptable with 75% certainty.

Limitations:

This evaluation is based on data from a single-center, non-randomized study. Preference weights or utilities were not available to calculate quality-adjusted life-years. Extra-mural costs were only partially evaluated from a hospital perspective. Indirect costs and economic consequences are not included.

Conclusions:

This economic evaluation compared direct medical costs associated with posaconazole or itraconazole treatment; the data suggest that posaconazole may be cost-effective as antifungal prophylaxis during the early high-risk neutropenic period and up to 100 days after allo-HSCT.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) has become a common procedure for patients with malignant and non-malignant hematologic disorders, causing a profound patient immune compromise and leading to a considerable risk and incidence of invasive fungal infection (IFI) in allo-HSCT recipientsCitation1. Early diagnosis of IFI is often difficult, and delays in diagnosis and treatment are associated with a mortality rate of 30–90%Citation2. Furthermore, antifungal treatment of established IFI has a high failure rate (60–70%) among allo-HSCT recipientsCitation3 and is associated with high healthcare costs (including antifungal therapy costs, costs of treating adverse events, and hospital resources)Citation4. For these reasons, current guidelines recommend primary antifungal prophylaxis as a management strategy in high-risk patients with hematologic disordersCitation5.

Posaconazole is an oral, extended-spectrum triazole effective against Candida spp and moulds (including Aspergillus spp, the Zygomycetes, and Fusarium)Citation6. In two large, prospective, randomized trials, primary prophylaxis with posaconazole was associated with fewer IFIs compared with standard azole therapy (fluconazole or itraconazole) in patients with neutropenia undergoing remission or induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and in patients with graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) following allo-HSCTCitation7,Citation8. The clinical data reported on the former trials have been extensively used to perform several modeled cost-effectiveness analyses in different countries; the outcomes of these economic analyses suggest that prophylaxis with posaconazole is a dominant or cost-effective option compared with standard azole therapy in the approved indications, including GVHD after allo-HSCTCitation9–14. Beyond GVHD, antifungal prophylaxis is also recommended during the early high-risk neutropenic phase and up to 100 days after allo-HSCT. Our group has recently published the first study suggesting that posaconazole antifungal prophylaxis, compared with itraconazole in the latter allo-HSCT clinical setting, might also reduce the incidence of IFI and improve IFI-free survival and overall survivalCitation15. Using clinical and safety data from this previous work, this study applied direct medical costs from a hospital perspective in Spain to conduct an economic evaluation to compare posaconazole with itraconazole as antifungal prophylaxis in allo-HSCT recipients.

Patients and methods

Patients

We conducted an observational study of adult patients (>18 years old) receiving antifungal prophylaxis for a first allo-HSCT between August 2005 and March 2009, at the Catalan Institute of Oncology, Hospital Duran i Reynals, Barcelona, SpainCitation15. Until the end of May 2007, prophylaxis consisted of itraconazole administered either as an oral solution (200 mg twice daily) or intravenously (200 mg twice daily for 2 days, followed by 200 mg once daily), depending on patient tolerance. From June 2007 onwards, and based on new evidence availableCitation7,Citation8, our local antifungal policy committee, with representatives from the Hospital Pharmacy and the Departments of Haematology and Infectious Diseases, changed the recommended antifungal prophylaxis to posaconazole oral solution 200 mg 3-times daily. In addition to prolonged neutropenia and GVHD, posaconazole was adopted into our protocol for primary antifungal prophylaxis during the early phase of allo-HSCT in the absence of GVHD, with a commitment to prospectively audit this experience and to compare it with our previous experience with itraconazole in this particular clinical setting. Allo-HSCT antifungal prophylaxis in our center was administered, regardless of the antifungal agent used, to cover both the post-transplantation neutropenic phase and the early post-engraftment phase, up to 100 days after transplantation, and discontinued at this point in the absence of GVHD. This study included all consecutive adult recipients of a first allo-HSCT with no previous history of IFI who received primary antifungal prophylaxis during the study period. Both treatment groups had the same management algorithmsCitation15.

Thirty-three allo-HSCT recipients (27 AML; 21 men; median age 48 [23–68]; 22 reduced intensity conditioning; 13 unrelated donor transplants with in vivo T-cell depletion) receiving posaconazole prophylaxis were compared with 16 itraconazole counterparts (eight AML; nine men; median age 46 [20–67]; six reduced intensity conditioning; two unrelated donor transplants). More patients receiving posaconazole were T-cell depleted (39% vs 0%; p = 0.003). Groups were otherwise comparable, in terms of patient and transplant characteristics and post-transplant complications including incidence of acute GVHD and cytomegalovirus reactivations (data not shown).

Clinical outcomes data

The clinical data required for the cost-effectiveness analysis, which consisted of the IFIs avoided and overall survival while patients received active prophylaxis, were obtained from our former observational study. The results of this study showed that patients receiving posaconazole had a reduced cumulative incidence of probable or proven IFI and an increased IFI-free survival and overall survival during the 100-day fixed prophylaxis period, compared with patients receiving itraconazoleCitation15.

Resource use and costs

Data on total costs of in-patient and out-patient medical resource use from a hospital perspective were recordedCitation16. The cost analysis does not include the cost derived from managing allogeneic donors and/or stem cell procurement or processing. All hospital-based costs were evaluated for every patient, starting from patient initial admission for allo-HSCT until day 100 after transplantation. Cost of hospital stay was included, taking into consideration whether the stay was in the general ward, the hematology transplant unit, or other special units such as the intensive care unit. Management of febrile neutropenia included chest radiography, urine and blood cultures, and combined empiric antibiotic treatment—namely, cefepime and amikacin—on the first day of neutropenic fever. Galactomannan enzyme immunoassay (Platelia® Aspergillus enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Redmond, WA) was performed in peripheral blood samples twice weekly. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) of the thorax was performed when unexplained fever persisted for >72 h despite empiric antibiotic therapy or when any clinical signs or symptoms developed. In the case of radiologic chest abnormalities and no other microbiologic evidence, bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed whenever possible for microbiologic testing, including galactomannan detection. Additional blood, sputum, and other relevant samples were collected for culture from possibly infected sites when clinically indicated. Change of antifungal treatment in this real-life experience relied on clinical judgment individualized for each patient, taking into consideration signs and symptoms, diagnostic test results, and patient drug tolerance and adherence. Diagnostic costs included microbiology tests (BAL, galactomannan detection in serum or BAL, cytomegalovirus antigenemia, polymerase chain reaction, urine and blood cultures, and staining and culture of sputum), radiology tests (chest radiographs, high-resolution CT scans), general laboratory tests (complete blood count, biochemistry, coagulation screenings, cyclosporine level detection), and other diagnostic consultations and procedures (bronchoscopy, CT-guided biopsies, skin biopsies, other medical or surgical consultations). Treatment costs included all blood product transfusions; antibiotic, antiviral, and antifungal drug use; transplant conditioning regimens; other general drugs for symptom control; and other therapeutic surgical or medical procedures. Unit costs, expressed in 2008 euros, were obtained from the hospital pharmacy, the drug database of the General Council of the Official College of PharmacistsCitation17, and the Spanish Health Costs databaseCitation18. Discounting does not apply to this study, given the short follow-up of patient management (maximum, 100 days after transplantation).

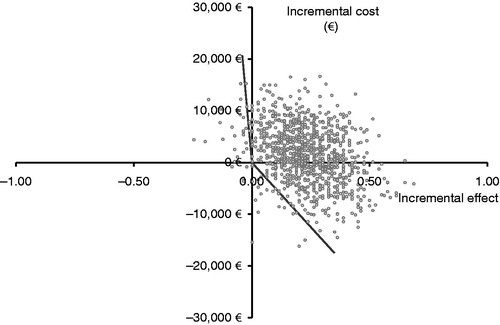

Economic and statistical analyses

In the original study, cumulative incidence of probable or proven IFI were compared between treatment groups using a Gray testCitation15. Clinical and economic data were then used to determine the incremental costs per IFI avoided and per life-year gained with posaconazole compared with those associated with itraconazole. Confidence intervals (CIs) for the incremental costs per life-year gained were calculated using a bootstrap procedure with a bias-corrected percentile methodCitation19. In such a procedure, a random sample with replacement is taken from the original sample of patients, for both groups, with a size equal to the original sample size (i.e., 16 patients in the itraconazole group and 33 patients in the posaconazole group). For such a bootstrap sample, the mean costs, effects, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) were calculated. This procedure was repeated 1000 times to assess the uncertainty surrounding the ICER. We chose to use the simple bias-corrected percentile method to adjust for any bias in the bootstrap distribution from which the CI limits would be taken. The bootstrapped ICERs and the CIs obtained with the bias-corrected percentile method were graphically represented on the cost-effectiveness plane.

With the outcomes of the bootstrap procedure, an acceptability curve was constructed. This curve shows for every threshold value the probability that the ICER is below that limit. Variations in cost or survival were included in the bootstrap estimates of the ICER. No sensitivity analysis was conducted.

Results

Clinical data

presents clinical data from the study. There were no significant differences between groups in the incidence of fever or of persistent fever (>72 h) or in the percentage of patients maintaining their antifungal prophylaxis for the 100-day fixed period. The incidence of IFI was significantly higher in patients taking itraconazole than in those taking posaconazole (12.5% vs 0; p = 0.04). Furthermore, IFI-free survival and overall survival were significantly greater for patients taking posaconazole than for those taking itraconazole (90.9% vs 56.3%, p = 0.003; and 90.9% vs 62.5%, p = 0.011, respectively).

Table 1. Clinical data from observational studyCitation15.

presents the incidence of grade III or IV antifungal drug toxicities, according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0Citation21. Grade III or IV elevations in alkaline phosphatase, alanine transaminase, and bilirubin were similar between groups. There were more grade III or IV elevations in gamma-glutamyltransferase in the posaconazole group (e.g., 33.3% vs 12.5% at week 4). However, 21.2% of posaconazole patients had grade III or IV elevations in gamma-glutamyltransferase before antifungal treatment began, compared with 0 itraconazole patients. This may be related to a higher percentage of patients undergoing in vivo T-cell depletion with alemtuzumab or thymoglobulin for unrelated donor transplantation in the posaconazole group (39% vs 0; p = 0.003)Citation15.

Table 2. Incidence of grade III or IVa antifungal drug toxicities, n (%), from observational studyCitation15.

Cost of allogeneic HSCT per patient from a hospital perspective

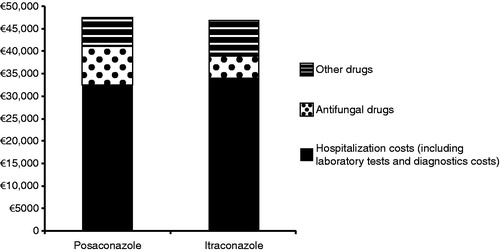

Unit costs of healthcare resources considered in the cost-effectiveness analysis are shown in in 2008 euros. Mean total cost of allo-HSCT per patient up to day 100 was €46,562.10 in the posaconazole group and €45,079.80 in the itraconazole group (). Allo-HSCT hospitalization costs (including hospital stay, laboratory tests, and diagnostic tests) exceeded €30,000. The mean cost per patient associated with posaconazole and itraconazole as initial medication was higher for posaconazole (€9376 vs €4944). However, hospitalization costs per patient (including laboratory tests and diagnostic costs) were higher for itraconazole than for posaconazole (€32,690 vs €31,272), and the costs of other drugs were also higher for the itraconazole group than for the posaconazole group (€7445 vs €5914).

Table 3. Costs of healthcare resources considered in the cost-effectiveness analysis.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

The difference in mean costs between the treatment arms was €1482 higher in the posaconazole group than in the itraconazole group because of the higher drug acquisition cost of posaconazole vs itraconazole. Nonetheless, posaconazole patients had a lower incidence of IFI than itraconazole patients (0 vs 12.5%)Citation15, which resulted in a cost-effectiveness ratio per IFI avoided with posaconazole of €11,856. Furthermore, patients receiving posaconazole had a higher overall survival during the 100-day fixed prophylaxis period than those receiving itraconazole (90% vs 62.5%)Citation15, resulting in a favorable cost-effectiveness ratio per life-year gained with posaconazole of €5218.

presents a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve; point estimates for ICERs, with the bias-corrected 95% CIs graphically presented on the cost-effectiveness plane with health effect expressed in life-years gained. Assuming a threshold of €30,000 per life-year gained, the ICER based on life-years gained is acceptable, with 75% certainty (). The results of the bootstrap analysis are presented in .

Figure 2. Acceptability curve presenting, for each possible threshold on the ICER, the probability that the ICER is acceptable. ICER indicates incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. Assuming a threshold of €30,000 per life-year gained, the ICER based on life-years gained is acceptable, with 75% certainty.

Discussion

Several studies have reported the cost-effectiveness of posaconazole in different patient populations using economic decision-analytic models with data derived from clinical trialsCitation9–14. One economic model developed to assess the cost-effectiveness of posaconazole vs standard azole therapy to prevent IFI was adapted by at least 11 countriesCitation9. The model showed that posaconazole was cost-saving or cost-effective vs fluconazole/itraconazole, with increases in life-years saved ranging from 0.016–0.1 yearsCitation9. Our economic analysis explores a different clinical setting during the neutropenic period after allo-HSCT and the early post-engraftment phase up to 100 days after allo-HSCT, and for this it relies on a comprehensive direct data collection of total hospital costs from inpatient and outpatient medical resource use. It is well known that IFI increases the duration of the hospital stay and the overall costCitation22,Citation23. For this reason, we included not only costs directly related to IFI prophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment but also every possible additional cost from a hospital perspective in order to have an idea of the relative contribution of IFI to the overall cost of the procedure and whether the change in strategy makes the whole procedure cost-effective. It should be noted that our analysis did not include donor and allo-HSCT-derived costs.

The cost per patient associated with initial prophylaxis was higher for posaconazole than for itraconazole. For itraconazole, intolerance to the oral formulation was the major clinical outcome that most influenced therapeutic cost; for posaconazole, the major clinical outcome affecting cost was the rate of success among patients who did not discontinue because of prophylaxis failure or intolerance.

The total cost of alternative drugs was higher with itraconazole than with posaconazole. However, hospitalization costs associated with the itraconazole group were higher than those associated with the posaconazole group because, although overall average durations of hospital stay in the posaconazole and itraconazole groups were similar, the duration of administration of high-cost alternative medication was longer in the itraconazole group than in the posaconazole group. Despite the lower treatment cost of itraconazole compared with posaconazole, the higher use of hospitalization resources and alternative drugs in the itraconazole group makes this alternative only €1482 less expensive per patient than the use of posaconazole as antifungal prophylaxis. In this study, posaconazole resulted in a favorable ICER of €11,856 per IFI avoided and €5218 per life-year gained. In previous cost-effectiveness analyses, prophylaxis with posaconazole was found to be cost-saving in most countriesCitation9. In Belgium and Germany, however, the cost per life-year saved was reported as €1173 and €6820, respectivelyCitation9; as in this study, the incremental cost was well below the pre-determined cost-effectiveness thresholds for these countries.

From a clinical standpoint, initial therapy with posaconazole demonstrated longer overall survival, and reduction in IFI incidence. Reduction in IFI incidence has been previously reported with posaconazole prophylaxis. In two large, prospective, randomized trials of primary prophylaxis vs standard azole therapy (fluconazole or itraconazole), breakthrough IFI incidence was lower with posaconazole treatment in neutropenic patients undergoing remission or induction chemotherapy for AML or MDS (2.3% vs 8.4%; p < 0.001)Citation7 and in patients with GVHD following allo-HSCT (2.4% vs 7.6%, p = 0.004)Citation8.

Study limitations

This economic evaluation is based on data from a single-center, non-randomized study, and an ideal evaluation would be based on data from double-blinded randomized clinical trials, from which the most robust evidence of efficacy could be drawn. Nonetheless, such robust data from randomized clinical trials are not available for the early phase after allo-HSCT. Thus, the use of study data from Sánchez-Ortega et al.Citation15, despite it being on historical cohorts from a single center study with a small number of cases of IFI, reflects valuable real-life clinical practice. In addition to the small number of subjects, the treatment groups were unbalanced, with 33 patients in the posaconazole group vs 16 patients in the itraconazole group.

Ideally, the ICER is expressed as costs per quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained. At the time of this study, however, no preference weights or utilities were available to calculate QALYs; therefore, we were not able to express the health effect in terms of QALYs gained.

Extra-mural costs were only partially evaluated from a hospital perspective, in terms of radiology CT scans and antifungal treatment provided by the hospital. Furthermore, this analysis leaves out indirect costs and economic consequences, such as productivity losses.

Costs were calculated in 2008 euros giving an ICER of €11,856 per IFI avoided and €5218 per life-year gained. However, when the costs were multiplied by the Spanish inflation index from 2008–2013Citation2Citation4 (∼14%), the 2013 values would be €16,598 per IFI avoided and €9148 per life-year gained, which is still within the threshold of €30,000 per life-year gained.

Conclusions

Our single center observational study confirms the results of published modeled economic evaluations and offers additional data regarding the costs of the procedure and the cost-effectiveness of posaconazole. While our study had a very low number of breakthrough IFIs, our data suggest that posaconazole may be cost-effective as antifungal prophylaxis during the early high-risk neutropenic period and up to 100 days after allo-HSCT.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Whitehouse Station, NJ, and MSD, Madrid, Spain.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

R.F.D. has received a grant from Schering-Plough; is a board member of Genzyme, Merck, Sanofi Oncology, and Schering-Plough; and has received payment for lectures/speaker bureaus from Amgen, Bristol Myers-Squibb, Celgene, Esteve, Genzyme, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Schering-Plough. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Sheena Hunt, PhD, of ApotheCom and paid for by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Whitehouse Station, NJ.

References

- Richardson MD. Changing patterns and trends in systemic fungal infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005;56:i5–i11

- Fukuda T, Boeckh M, Carter RA, et al. Risks and outcomes of invasive fungal infections in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Blood 2003;102:827–33

- Caggiano V, Weiss RV, Rickert TS, et al. Incidence, cost, and mortality of neutropenia hospitalization associated with chemotherapy. Cancer 2005;103:1916–24

- Jansen JP, Meis JF, Blijlevens NM, et al. Economic evaluation of voriconazole in the treatment of invasive aspergillosis in the Netherlands. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:1535–46

- Maertens J, Marchetti O, Herbrecht R, et al. European guidelines for antifungal management in leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: summary of the ECIL 3-2009 update. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:709–18.

- Keating GM. Posaconazole. Drugs 2005;65:1553–67

- Cornely OA, Maertens J, Winston DJ, et al. Posaconazole vs. fluconazole or itraconazole prophylaxis in patients with neutropenia. N Engl J Med 2007;356:348–59

- Ullmann AJ, Lipton JH, Vesole DH, et al. Posaconazole or fluconazole for prophylaxis in severe graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med 2007;356:335–47

- Papadopoulos G, Hunt S, Prasad M. Adapting a global cost-effectiveness model to local country requirements: posaconazole case study. J Med Econ 2013;16:374–80

- Stam WB, O'Sullivan AK, Rijnders B, et al. Economic evaluation of posaconazole versus standard azole prophylaxis in high risk neutropenic patients in the Netherlands. Eur J Haematol 2008;81:467–74

- Collins CD, Ellis JJ, Kaul DR. Comparative cost-effectiveness of posaconazole versus fluconazole or itraconazole prophylaxis in patients with prolonged neutropenia. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2008;65:2237–43

- De la Camara R, Jarque I, Sanz MA, et al. Economic evaluation of posaconazole vs fluconazole in the prevention of invasive fungal infections in patients with GVHD following haematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45:925–32

- Michallet M, Gangneux JP, Lafuma A, et al. Cost effectiveness of posaconazole in the prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections in acute leukaemia patients for the French healthcare system. J Med Econ 2011;14:28–35

- Lyseng-Williamson KA. Posaconazole: a pharmacoeconomic review of its use in the prophylaxis of invasive fungal disease in immunocompromised hosts. PharmacoEconomics 2011;29:251–68

- Sanchez-Ortega I, Patino B, Arnan M, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of primary antifungal prophylaxis with posaconazole vs itraconazole in allogeneic blood and marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:733–9

- Drummond MF, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL, et al. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes, 2nd edn. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1997

- Spanish General Council of Pharmacists (Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmaceuticos). Database of medicines. https://botplusweb.portalfarma.com/botplus.asp. Accessed July 27, 2011

- Spanish Health Costs (CD-ROM database). Barcelona: Centre d’Estudis en Economia de la Salut de la Politica Socia, 2005. SOIKOS version 2.2

- Campbell MK, Torgerson DJ. Bootstrapping: estimating confidence intervals for cost-effectiveness ratios. QJM 1999;92:177–82

- De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:1813–21

- National Cancer Institute. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE), v3.0. 2006. http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_30. Accessed

- Menzin J, Meyers JL, Friedman M, et al. Mortality, length of hospitalization, and costs associated with invasive fungal infections in high-risk patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2009;66:1711–7

- van Gool R. The cost of treating systemic fungal infections. Drugs 2001;61:49–56

- Worldwide inflation data. http://www.inflation.eu/inflation-rates/spain/historic-inflation. Accessed March 7, 2013