Abstract

Objective:

To assess the cost-effectiveness of subcutaneous interferon (sc IFN) beta-1a 44 mcg 3-times weekly (tiw) vs no treatment at reducing the risk of conversion to multiple sclerosis (MS) in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) in Sweden.

Methods:

A Markov model was constructed to simulate the clinical course of patients with CIS treated with sc IFN beta-1a 44 mcg tiw or no treatment over a 40-year time horizon. Costs were estimated from a societal perspective in 2012 Swedish kronor (SEK). Treatment efficacy data were derived from the REFLEX trial; resource use and quality-of-life (QoL) data were obtained from the literature. Costs and outcomes were discounted at 3%. Sensitivity analyses explored whether results were robust to changes in input values and use of Poser criteria.

Results:

Using McDonald criteria sc IFN beta-1a was cost-saving and more effective (i.e., dominant) vs no treatment. Gains in progression free life years (PFLYs) and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were 1.63 and 0.53, respectively. Projected cost savings were 270,263 SEK. For Poser criteria cost savings of 823,459 SEK were estimated, with PFLY and QALY gains of 4.12 and 1.38, respectively. Subcutaneous IFN beta-1a remained dominant from a payer perspective. Results were insensitive to key input variation. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis estimated a 99.9% likelihood of cost-effectiveness at a willingness-to-pay threshold of 500,000 SEK/QALY.

Conclusion:

Subcutaneous IFN beta-1a is a cost-effective option for the treatment of patients at high risk of MS conversion. It is associated with lower costs, greater QALY gains, and more time free of MS.

Limitations:

The risk of conversion from CIS to MS was extrapolated from 2-year trial data. Treatment benefit was assumed to persist over the model duration, although long-term data to support this are unavailable. Cost and QoL data from MS patients were assumed applicable to CIS patients.

Introduction

Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) is defined as the first occurrence of a single demyelinating event in one or more sites in the central nervous system lasting more than 24 h. CIS confers an elevated risk of progression to multiple sclerosis (MS), with a recent study demonstrating that 66% of CIS patients converted to McDonald (2005) criteria MSCitation1. Conversion rates in high risk populations may be raised further, particularly when revised 2010 McDonald criteria are applied for diagnosis. Globally CIS prevalence is yet to be robustly characterized, although a recent study in the US estimates incidence to be 3.4 per 100,000 person yearsCitation2. MS prevalence in Sweden has been more clearly documented, and is estimated to be 188.9/100,000, amongst the highest in the worldCitation3.

MS patients face progressively deteriorating quality-of-life and incur substantial disease-related expenditures. Overall costs resulting from MS in Sweden have been estimated to be €600 million per yearCitation4. Early treatment with disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) is approved for CIS, and has been increasingly advocated to reduce the risk of MS conversion. Available DMDs include interferon-beta (IFNß) as well as glatiramer acetate. Subcutaneous (sc) IFN ß-1a (Rebif®) belongs to the class of IFNs currently used for MS therapy, and has recently been licensed for treatment of patients with CIS based on results of the REFLEX phase three randomized controlled clinical trialCitation5.

The present study sought to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of sc IFN ß-1a 3-times weekly (tiw) treatment for patients with clinically isolated syndrome. An economic model was constructed to simulate projected costs incurred by CIS patients over time, estimated quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) experienced, and the total number of life years spent free from MS, when comparing treatment with sc IFN ß-1a tiw to no treatment.

Methods

A Markov model was used to simulate the clinical course of a cohort of CIS patients over a 40-year time horizon. The population included in the model analysis comprised patients who had experienced a single demyelinating event in one or several areas of the central nervous system within the previous 2 months, at a high risk of conversion to MS, with a mean age of 31 years, as per the 2-year, double blinded REFLEX trialCitation5. The choice of time horizon reflected the potential long-term implications of MS and the recommendation of a lifelong time horizon in Swedish pharmacoeconomic guidelinesCitation6. Patients were treated with sc IFN ß-1a tiw or received no treatment, and the projected clinical outcomes and costs incurred in both cohorts were compared.

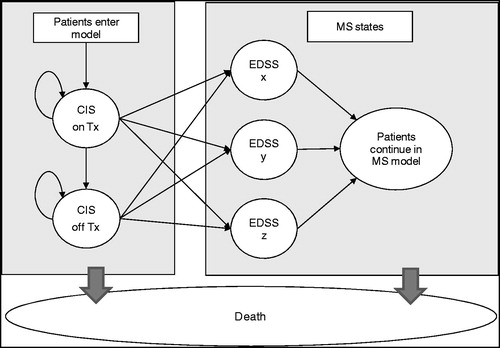

Markov models permit categorisation of patients into a number of discrete, mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive health states, between which they can transition over time. Such models are commonly used in pharmacoeconomic assessmentCitation7. All patients entering the model started in the CIS state, and were assumed to be either treated with sc IFN ß-1a tiw or to receive no treatment. Every yearly model cycle patients faced defined probabilities of staying in this state, discontinuing treatment, or transitioning to relapsing remitting MS (RRMS). If patients converted to MS, during subsequent model cycles they were similarly able to stay in state, progress to a more advanced RRMS state, or convert to secondary progressive MS (SPMS). Both RRMS and SPMS states were differentiated by Expanded Disability Status Score (EDSS), and patients were permitted to progress through EDSS states in single step increments, e.g., from EDSS 3 to 4 or EDSS 7 to 8 according to a published algorithmCitation8. Health state membership was corrected using a half-cycle correction. Patients in all model states experienced the risk of mortality. A simplified model schematic is shown in .

Figure 1. Model schematic. CIS, clinically isolated syndrome; Tx, treatment; EDSS, expanded disability status scale; MS, multiple sclerosis.

Base case analyses used the McDonald criteria for MS diagnosis, due to its more common application in clinical practice vs the alternative Poser criteriaCitation9. The 2005 McDonald criteria were used, as per the REFLEX trial, rather than the more recent 2010 criteria. The 2005 McDonald criteria for MS are defined as central nervous system damage that is disseminated in time (i.e., on different dates) and space (at least two different parts of the central nervous system), that can be detected by MRI scans, whilst the Poser criteria for MS is defined as the occurrence of two clinically demyelinating events. Scenario analyses using the Poser criteria were also undertaken.

To model the baseline risk of untreated CIS patients converting to RRMS, data from the REFLEX trialCitation5 were used. Patient conversion in the first 2 years was taken directly from trial results. For subsequent model years, REFLEX data were extrapolated to generate the estimated risk of conversion to MS over time. Amongst several parametric models tested, a Weibull model was chosen for the extrapolation. The curve’s goodness of fit, and the consistency between its shape and expected disease clinical course were both factors considered in selecting the Weibull model as the most suitable predictor of subsequent conversion risk. For Poser criteria analyses a similar extrapolation was performed, using data from a long-term study of CIS patients documenting Poser criteria MS conversion over a 20 year periodCitation10. A Gompertz model was selected as the most suitable amongst alternatives tested. All CIS patients in the model were assigned an EDSS score derived from REFLEX data.

To model the effect of treatment, the hazard ratio for sc IFN ß-1a tiw from REFLEX (0.49, 95% CI = 0.38–0.64)Citation5 was applied to the baseline probability of conversion to MS, reducing the risk accordingly (for year 3, data in treated patients from the REFLEXION follow-up trialCitation11 were used to model treated patient conversion directly). Treatment benefit was assumed to persist over time; however, upon patient conversion to MS, no residual treatment benefit from prior therapy in the CIS phase was assumed. On the basis of clinical judgment, a maximum duration of treatment in the CIS phase of 25 years was implemented.

Each year, patients faced a defined risk of treatment discontinuation. For the first 2 model years, discontinuation data from the REFLEX trialCitation5 were applied, whilst data from REFLEXIONCitation11 were applied in year 3. In subsequent model years, the probability of treatment discontinuation was assumed equivalent to the year 3 rate derived from REFLEXION, until year 25 when treatment was ceased.

Clinical evidence indicates that not all CIS patients ultimately convert to MSCitation12, therefore allowing unlimited patient conversion would permit a treatment benefit to be modeled in some patients who in practice would never convert. Consequently, a cumulative conversion threshold was applied that limited the overall proportion of patients able to convert to MS. This cap was set to 95% for the McDonald criteria, a figure derived by using available 5-year data from another studyCitation13 to estimate the proportion of REFLEX patients who would have converted at the same time point via an indirect comparison. The predicted proportion of REFLEX patients converting after 5 years was assumed to be a suitable overall conversion threshold in the model.

Once patients in the model had converted to RRMS, the probabilities of progressing through EDSS states and converting to SPMS were derived from the London Ontario data setCitation8. In the MS phase, the treatment effect applied to patients was assumed to be a weighted mix of DMDs, according to their market shares (22.2% glatiramer acetate and 77.8% interferons), with the relative treatment effects derived from a meta-analysis (data available on request). This reflected average treatment prescribing decisions in the MS phase in the absence of data on switching preferences upon MS conversion. The mixed treatment assumption also preserved the link between initial treatment in the CIS phase and observed model outcomes, precluding confounding of results caused by differential treatment in the MS phase. This permitted more direct evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of sc IFN ß-1a tiw for CIS treatment. Patients in the MS phase of the model reaching EDSS 7 or converting to SPMS were assumed to discontinue treatment.

Quality-of-life scores (utilities) associated with each EDSS level were obtained from a study in MS patientsCitation4, and applied to all model patients according to EDSS score. Utility studies from CIS patients were not available; hence, it was assumed that data from MS patients could be applied.

Costs associated with each EDSS level were derived from the same study, using the software GetData Graph Digitizer v2.24Citation1Citation4 to determine point estimates from graphical outputs. Direct costs, as defined in Berg et al.Citation4, included costs related to informal care, services, investments (house and car modifications, walking aides, wheelchairs, etc.), non-DMD drugs, tests, ambulatory care, and inpatient care; indirect costs included the cost of lost productivity as a result of early retirement and short-term absence; indirect costs were only applied when model patients were under retirement age (65 in Sweden). The largest contributors to direct and indirect costs were found by Berg et al.Citation4 to be services and early retirement, respectively. All costs were converted from 2005 Euros to 2005 Swedish kronor (SEK) using the historical average exchange rate from 2005 (9.28 SEK per euro)Citation15, and then inflated from average 2005 SEK to March 2012 SEK using the Swedish Consumer Price Index ratioCitation16 (314.8/280.4). summarises the direct and indirect health state costs applied in the model in 2012 SEK. As with utility values, EDSS specific costs were assumed applicable to both CIS and MS patients.

Table 1. Heath state costs and utility values by EDSS score.

Additional resource utilisation associated with disease monitoring was applied in the model for CIS patients following discussion with clinicians. CIS patients were assumed to undergo MRI scans of the brain and spinal cord in the first year of diagnosis, and a brain MRI scan in every year thereafter.

The drug cost of sc IFN ß-1a tiw treatment in the CIS phase was assumed equivalent to its cost when used for MS treatment, resulting in an annual treatment cost of 121,973 SEK. Post-conversion to RRMS, treatment costs were assumed to be a weighted average of the market basket using drug costs obtained from the TLVCitation17; 22.2% of patients were assumed to be treated with glatiramer acetate and 77.8% of patients were assumed to be treated with interferons to give a weighted average annual treatment cost of 116,968 SEK in the MS phase. Future costs and outcomes were discounted at 3%Citation6.

Mortality rates for all model patients were adjusted to reflect the heightened risk of death caused by disease-related disability. Swedish background mortality dataCitation18 were multiplied by EDSS-specific adjustment factorsCitation19, resulting in elevated mortality risk with increasing disease severity.

A series of univariate sensitivity analyses were undertaken by varying the values of key model parameters within plausible ranges and exploring the robustness of model results to these changes. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis, a stochastic analysis which explores second order uncertainty in the model and evaluates overall robustness, was also conducted. One thousand simulations were performed, each time varying all inputs subject to second order uncertainty within logical ranges by sampling according to pre-defined distributions for each parameter. Covariance associated with variables used in the parametric extrapolation was accounted for.

Results

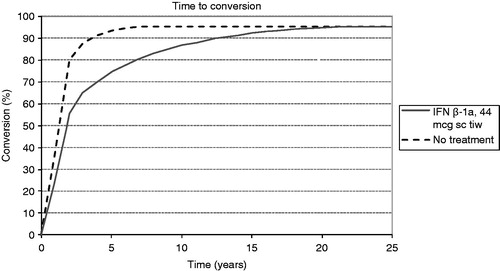

Analysis using the McDonald 2005 criteria indicated that treatment with sc IFN ß-1a tiw substantially delays patient conversion to MS vs no treatment. In our model, treated CIS patients took ∼22 years to reach the 95% conversion limit applied, whilst in the no treatment arm patients reached this cap after only 8 years, as shown in .

Treated patients experienced a greater number of progression-free life years (PFLYs), i.e., years spent free from MS, with an incremental gain vs no treatment of 1.63 PFLYs per patient. Benefits in QALYs were also projected, with an incremental QALY gain of 0.53 per patient. These clinical benefits were complemented by estimated cost savings of 270,263 SEK from treatment, according to the societal perspective, as shown in . The estimated clinical benefit and reduction in costs translated into predicted cost-effectiveness for sc IFN ß-1a tiw, which was dominant vs no treatment. Due to the dominance of sc IFN ß-1a tiw, the net monetary benefit is also shown in in order to quantify cost-effectivenessCitation7,Citation20.

Table 2. Cost-effectiveness of sc IFN beta-1a tiw vs no treatment.

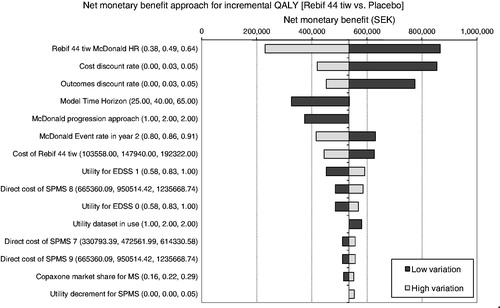

Univariate sensitivity analysis results presented via the tornado diagram in illustrate the 15 parameters to which model results were most sensitive. The tornado diagram shows that base case cost-effectiveness estimates were robust to changes in the values of key model parameters, with sc IFN ß-1a tiw remaining cost-effective (with a positive net monetary benefit) for all parameter variations tested.

Figure 3. One-way sensitivity analysis tornado diagram. Note, this figure illustrates the variation from the base-case net monetary benefit (535,118 SEK) found when individual model parameters were changed. Values in parentheses represent the lower, base-case, and upper values tested in the sensitivity analysis. EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; HR, hazard ratio; IFN, interferon; sc, subcutaneously; SPMS, secondary progressive MS; tiw, 3-times weekly. For ‘McDonald progression approach’, 1 = constant probability of conversion to MS, 2 = parametric extrapolation used in base case. For ‘Utility dataset in use’, 1 = UK dataset26, 2 = Swedish dataset used in base case4.

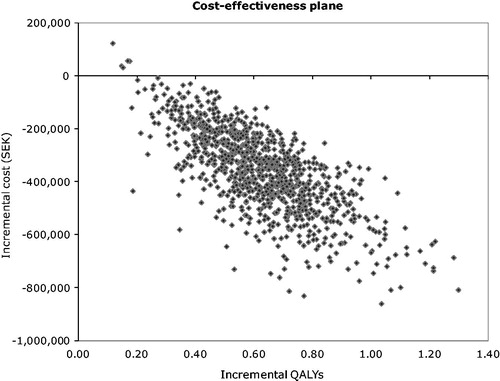

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis indicated a 99.9% likelihood of cost-effectiveness at the assumed willingness-to-pay threshold in Sweden of 500,000 SEK/QALYCitation21,Citation22. Of 1000 PSA simulations conducted, 99.5% generated results where both cost savings and QALY gains were achieved, as shown in . These results serve to illustrate the robustness of model results to fluctuations in the values of model parameters, strengthening the reliability of the base case results generated.

Figure 4. Cost-effectiveness plane showing incremental cost vs incremental QALYs for each PSA iteration.

Economic analysis using the Poser criteria for MS diagnosis exhibited similar trends to those observed with McDonald criteria, with accentuated clinical benefits and cost savings. Subcutaneous IFN ß-1a tiw treatment resulted in estimated cost savings of 823,459 SEK, with PFLY and QALY gains of 4.12 and 1.38, respectively.

Discussion

Early treatment with sc IFN β-1a tiw of patients with CIS at high risk of MS conversion was found to be a cost-effective option from both the societal and payer perspectives. It was associated with more time free of MS, lower costs, and QALY gains. The model was robust to plausible changes in key parameter values. Cost savings vs no treatment were driven primarily by reduced disease management costs, with delayed conversion reducing the duration of time spent in the high cost MS states.

The current study represents the first cost-effectiveness analysis in CIS using the McDonald 2005 criteria for diagnosis, although new (2010) McDonald criteria have been recently developedCitation23. Whilst other cost-effectiveness studies have been conducted in CISCitation24,Citation25, the ability to compare the current results to these studies was limited, due to the existence of significant heterogeneity between patient populations used in the respective clinical trials informing each model, as well as the absence of reported McDonald criteria data in other CIS trials.

The extrapolation of conversion risk used in the model generated estimated conversion after 3 years that was closely aligned with the actual conversion rate observed at year 3 from REFLEXIONCitation11. The predicted conversion profile was also judged by clinicians to broadly reflect medical experience with CIS patients. Nonetheless, extrapolating conversion risk over time faces limitations, and cannot currently be validated by existing data. Longer term data on MS conversion risk for the McDonald criteria will enhance the precision of future modeling efforts.

The assumption of persistent treatment benefit over time is also a limitation. Long-term data illustrating sustained treatment benefit are not currently available, and it is possible that confounding factors, such as neutralising anti-bodies, may attenuate the treatment effect over extended time horizons. Subsequent analyses might assess the expected impact of reduced effectiveness over time, but available data do not yet support an informed approach to doing this. A 5-year follow-up study of patients in the REFLEX trial is currently ongoing.

Costs and health-related quality-of-life associated with MS have been well documented; however, little has been published in CIS. The application of data from MS patients to a CIS population was informed by expert opinion. However, whilst the assumption that EDSS states are likely to display a consistent relationship with utility and management costs regardless of disease stage is plausible, there are no data to support this. Data derived specifically from CIS populations may augment the robustness of future modeling work.

Conclusion

Subcutaneous IFN β-1a is a cost-effective option for the treatment of patients at high risk of MS conversion when compared to no treatment in the Swedish setting. It is associated with lower costs, greater QALY gains, and more time free of MS.

QALY and PFLY gains could be generalised to other settings; however, cost inputs used in the model were specific to the Swedish setting and should be specified on a country-to-country basis to determine cost-effectiveness.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Merck Serono S.A. and Merck AB, and employees had input in the development of this study and manuscript (see author declarations below).

Declaration of financial/other relationships

SF, DB, and AC have received honoraria for consultancy work performed for Merck Serono S.A. including input provided for the current study. EM, NH, AP, and JL are employees of IMS Health, who served as paid consultants to Merck Serono S.A. during the development of this study and manuscript. MC was an employee of Merck Serono S.A. during the development of this study. LF is an employee of Merck AB. RP is an employee of Merck Serono Ltd. JME Peer Reviewers of this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

References

- Chard DT, Dalton CM, Swanton J, et al. MRI only conversion to multiple sclerosis following a clinically isolated syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 2001;82:176-9

- Langer-Gould A, Brara S, Beaber B, et al. (2012). the incidence of clinically isolated syndrome is higher in African Americans and whites compared with Hispanics and Asians. Neurology 2012;78:Meeting Abstracts 1

- Ahlgren C, Odén A, Lycke J. High nationwide prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Sweden. Mult Scler 2011;17:901-8

- Berg J, Lindgren P, Fredrikson S, et al. Costs and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in Sweden. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7(2 Suppl):S75-S85

- Comi G, De Stefano N, Freedman MS, et al. Comparison of two dosing frequencies of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in patients with a first clinical demyelinating event suggestive of multiple sclerosis (REFLEX): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:1, 33-41.

- Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency. General guidelines for economic evaluations from the Pharmaceutical Benefits Board (LFNAR 2003:2). Stockholm, Sweden: Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency. 2003. Available at: http://www.tlv.se/Upload/English/Guidelines-for-economic-evaluations-LFNAR-2003-2.pdf. Accessed 14 March 2013

- Briggs A, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2006

- Tappenden P, Chilcott J, O’Hagan T, et al. (2001). Cost-effectiveness of beta-interferons and glatiramer acetate in the management of multiple sclerosis: final report to the National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Sheffield, UK: School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), 2001.

- World Health Organization/Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Atlas: Multiple Sclerosis Resources in the World. Switzerland, Geneva: World Health Organization. 2008

- Fisniku LK, Brex PA, Altmann DR, et al. Disability and T2 MRI lesions: a 20-year follow-up of patients with relapse onset of multiple sclerosis. Brain 2008;131:3-17

- Comi G, Freedman MS, De Stefano N, et al. Effect of two dosing frequencies of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a on conversion to MS and MRI measures of disease in patients with a first clinical demyelinating event: 3-year results of Phase III, double-blind, multicentre trials (REFLEX/REFLEXION). Lyon, France: ECTRIMS, 2012.

- Brex PA, Miszkiel KA, O'Riordan JI, et al. MRI only conversion to multiple sclerosis following a clinically isolated syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;70:390-3

- Kappos, L, Freedman MS, Polman CH, et al. Long-term effect of early treatment with interferon beta-1b after a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis: 5-year active treatment extension of the phase 3 BENEFIT trial. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:987-97

- GetData Graph Digitizer v2.24. 2012. http://getdata-graph-digitizer.com/. Accessed December 19, 2012.

- Oanda. New York, United States: OANDA Corporation. 2012. http://www.oanda.com/currency/historical-rates/. Accessed December 19, 2012.

- Statistics Sweden. Consumer Price Index. Stockholm, Sweden: Statistics Sweden. 2012. http://www.scb.se/Pages/TableAndChart____272152.aspx. Accessed February 28, 2013.

- Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency. Drug Price Database. Stockholm, Sweden: Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency. 2012. http://www.tlv.se/beslut/sok/lakemedel/. Accessed December 19, 2012.

- Statistics Sweden. Life tables 2006--2010. Stockholm, Sweden: Statistics Sweden. 2012. http://www.scb.se/Statistik/BE/BE0701/2001I10/Figur_3.xls. Accessed December 19, 2012.

- Sadovnick AD, Ebers GC, Wilson RW, et al. Life expectancy in patients attending multiple sclerosis clinics. Neurology 1992;42:991-4

- Stinnett AA, Mullahy J. Net health benefits: a new framework for the analysis of uncertainty in cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Decis Making 1998;18(Suppl):S68-80

- Schwander B, Gradl B, Zöllner Y, et al. Cost-utility analysis of eprosartan compared to enalapril in primary prevention and nitrendipine in secondary prevention in Europe – The HEALTH Model. Value Health 2009;12:857-71

- Sorenson C. Use of comparative effectiveness research in drug coverage and pricing decisions: a six-country comparison. Commonwealth Fund Pub 2010;91:1-13

- Polman CH, Reingold C, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 Revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292-302

- Iskedjian M, Walker JH, Gray T, et al. Economic evaluation of Avonex (interferon beta-Ia) in patients following a single demyelinating event. Mult Scler 2005;11:542-51

- Lazzaro C, Bianchi C, Peracino L, et al. Economic evaluation of treating clinically isolated syndrome and subsequent multiple sclerosis with interferon beta-1b. Neurol Sci 2009;3:21-31

- Orme M, Kerrigan J, Tyas D, et al. The effect of disease, functional status, and relapses on the utility of people with multiple sclerosis in the UK. Value Health 2007;10:54-60