Abstract

Objective:

To compare changes in healthcare resource utilization and costs among members with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy (pDPN), postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), or fibromyalgia (FM) in a commercial health plan implementing pregabalin step-therapy with members in unrestricted plans.

Methods:

Retrospective study of outcomes associated with implementation of a pregabalin step-therapy protocol using claims data from Humana (‘restricted’ cohort) and Thomson Reuters MarketScan (‘unrestricted’ cohort). Members aged 18–65 years receiving treatment for pDPN, PHN, or FM during 2008 or 2009 were identified; cohorts were matched on diagnosis and geographic region. Baseline to follow-up changes in healthcare resource utilization and costs were determined using difference-in-differences (DID) analysis. Statistical models adjusting for covariates explored relationships between restricted access and outcomes.

Results:

A total of 3876 restricted cohort members were identified and matched to 3876 unrestricted cohort members. FM was the predominant diagnosis (84.7%). The unrestricted cohort was older (mean = 49.0 (SD = 10.4) years vs 47.6 (SD = 10.5) years; p < 0.001), and had greater comorbidity (RxRisk-V score = 5.4 (SD = 3.2) vs 4.4 (SD = 2.9), p < 0.001) than the restricted cohort. Compared with the unrestricted cohort, the restricted cohort demonstrated a greater year-over-year decrease in pregabalin utilization (−2.6%, p = 0.008), and greater increases in physical therapy and disease-related outpatient utilization (3.7%, p = 0.010 and 3.6%, p = 0.022, respectively). There were no statistically significant net differences in all-cause or disease-related total healthcare, medical, or pharmacy costs between cohorts. After adjusting for baseline compositional differences between cohorts, restricted plan membership was associated with a net increase in all-cause medical ($1222; p = 0.016) and disease-related healthcare costs ($859; p = 0.002). Limitations include use of a combined analysis for pDPN, PHN, and FM, especially since the observed results were likely driven by FM; an inability to link the prescribing of a medication with the condition of interest, which is common to claims analyses; and lack of pain severity information.

Conclusions:

Implementation of a pregabalin step-therapy protocol resulted in lower pregabalin utilization, but this restriction was not associated with reductions in total healthcare costs, medical costs, or pharmacy costs.

Introduction

Containment of healthcare costs frequently focuses on control of pharmacy spending by initiating formulary management strategies such as prior authorization policies or step-therapy protocols. A recent survey showed that these two strategies were used by ∼79% and 50% of employers, respectively, in calendar year 2011Citation1. Whereas prior authorization requires a patient to obtain prior approval from the health plan in order to receive reimbursement for a prescription medication that is not covered, step therapy formulary policies generally require use of alternative, less expensive medications before initiating treatment with branded or more expensive therapies. These less expensive medications are often generic, and in some cases may not necessarily be approved for the indication.

Several studies have suggested that, while these policies may reduce pharmacy costsCitation2–6, they may also have the unintended consequence of acting as a barrier to medication utilization, with step-therapy protocols in particular resulting in fewer patients filling prescriptionsCitation2,Citation6. Furthermore, pharmacy spending represents only a single component of total healthcare costs. The few studies that have evaluated the effects of these policies on disease-related or total healthcare resource utilization and costs reported no overall cost savings associated with initiation of either prior authorizationCitation7,Citation8 or step-therapy protocolsCitation9,Citation10; any observed cost savings were offset by an increase in other component costs.

The anticonvulsant pregabalin is an alpha2-delta ligand that is approved for the management of several chronic pain conditions including fibromyalgia (FM) as well as neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (pDPN), post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), and spinal cord injury-associated neuropathic painCitation11. Evidence suggests that initiation of a prior authorization policy for pregabalin to reduce pharmacy costs associated with the treatment of pDPN or PHN has no effect on total disease-related costs. In a Medicaid population, implementation of pregabalin prior authorization for the treatment of pDPN and PHN was associated with increased use of other pain medications and resulted in increased disease-related total healthcare costsCitation7. Similar restrictions in a commercially-insured population showed no significant effect on pDPN- or PHN-specific medication or healthcare expendituresCitation8. No studies have yet evaluated the impact of restricting access to pregabalin among patients with FM, nor have studies been done to determine the impact on medical costs of restricting pregabalin use via initiation of a step-therapy protocol.

In January 2009, Humana implemented a step-therapy protocol for new starts to pregabalin for all approved indications at that time other than for treatment for seizure disorders. In order for a member to receive health plan coverage of pregabalin for the treatment of pDPN, PHN, or FM, the member must have had an adherent treatment trial of gabapentin, defined as having a medication possession ration between 50–66% or 90–120 days’ supply filled during a consecutive 6 month period within the last 12 months. Gabapentin is FDA-approved for the treatment of PHNCitation12. However, gabapentin does not have an FDA-approved indication for the treatment of FM or pDPNCitation12, although limited data from clinical trials have suggested its efficacy for improvement in pain and other outcomes including sleep in patients with these conditionsCitation13,Citation14. Initiation of the step-edit protocol provided an opportunity to evaluate the effects of this type of cost containment policy on resource utilization and costs among commercial health plan members.

Patients and methods

Study design and populations

This retrospective, observational study was of parallel-group design and used two cohorts matched (1:1) on diagnosis and geographic region. Cohort 1 was a pregabalin-restricted cohort from the Humana pharmacy and medical claims database which contains pharmacy, medical, and eligibility information for 1.5 million fully-insured commercial members covered under preferred provider organizations, point of service plans, and health maintenance organizations. A step-therapy protocol for pregabalin was implemented within these plans on 1 January 2009. Cohort 2 was an unrestricted cohort from the Thomson Reuters MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Database. This database includes longitudinal records of inpatient services, outpatient services, long-term care, and prescription drug claims covered under a variety of fee-for-service and capitated health plans, including exclusive provider organizations, preferred provider organizations, point of service plans, indemnity plans, and health maintenance organizations. The data are nationally representative, quality controlled, and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) compliant. The 12-month period for calendar year 2008 was the pre-index period (baseline), and the post-index period (follow-up) was the calendar year from the introduction of the step-therapy protocol through 31 December 2009. The research protocol was approved prior to study initiation by an independent Institutional Review Board and was granted a waiver of informed consent and a waiver of HIPPA authorization.

Study subjects were those with continuous enrolment in a fully-insured commercial plan for calendar years 2008 and 2009 who met all of the following criteria: 18–64 years of age, inclusive; ≥1 medical claim with an International Classification of Disease, 9th edition, clinical medication (ICD-9) code for pDPN (250.6x or 357.2x), PHN (053.1x), or FM (729.1) during the study period, and at least one pharmacy claim for a medication potentially used to treat pDPN, PHN, and FM, or a medical claim for a pain intervention procedure within 60 days after diagnosis. Subjects were excluded if they had any claim for epilepsy (ICD-9 codes 345.xx and 780.39), cancer—not including basal cell and squamous cell cancers and benign neoplasms (ICD-9 CM 140.xx-172.xx, 174.xx-208.xx, 235.xx-239.xx), or transplant surgery; were a resident in a long-term care facility for ≥90 days; or were diagnosed with more than one of the conditions of interest. The subject selection criteria were applied to both data sources to identify subjects eligible for matching. After application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria, a 1:1 individual match on diagnosis and geographic regions was conducted.

Outcomes evaluated

The RxRisk-V was used to characterize members in terms of comorbidity burden. The RxRisk-V is a comorbidity measure for 45 distinct chronic disease states that are identified from drug claims data for pharmacologic treatments associated with each disease stateCitation15–17.

All-cause and disease-related healthcare resource utilization and costs were determined based on claims. Resource categories included outpatient visits, emergency room visits, inpatient visits, physical therapy, and pharmacy. Physical therapy claims were identified by the use of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 97001–97039, 97110–97150, and 97530–97799 to document physical therapy encounters. Disease-related utilization was based on the presence of a diagnosis code for pDPN, PHN, or FM associated with the outpatient, inpatient, emergency room, or physical therapy claim. Pharmacy claims for medications generally used to treat pDPN, PHN, and FM were specifically evaluated based on number and proportion of unique members with a prescription claim adjudicated during the pre- and post-index periods. In addition to pregabalin, these medications included opioids, non-opioid analgesics, antidepressants, first and second generation anticonvulsants, anaesthetics (lidocaine), and muscle relaxants. Other than pregabalin and gabapentin, these drugs were evaluated based on ‘drug class’, and there were no restriction policies at the class level for any drug classes specified in this study. Both member share and plan-paid costs were included in determination of medical and pharmacy costs, and costs were determined based on reported financial data directly associated with each medical claim.

Statistical analysis

Bivariate descriptive statistics were used to characterize both cohorts, and baseline characteristics were compared between the pregabalin-restricted cohort and the unrestricted cohort.

Pre- to post-index changes in disease-related and all-cause utilization and costs were compared between cohorts using a ‘difference-in-differences’ (DID) analysis whereby the pre–post-index differences were calculated within each cohort and the net difference between cohorts was determined as: DID = (Restricted cohort2009 − Restricted cohort2008) − (Unrestricted cohort2009 − Unrestricted cohort2008).

Several statistical models were used to explore relationships between restricted access and outcomes, based on the type of data being modeled (e.g., dichotomous outcome, count, cost data). Conditional logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between restriction status (the predictor of interest) and the likelihood of pregabalin use (dependent variable, yes or no) in the post-index periodCitation18. Covariates included in the conditional logistic regression model were age, gender, geographic region, diagnosis, plan type, and RxRisk-V score. Multivariate models using generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were used to model medication utilization and cost outcomes while accounting for within-subject correlation, as well as within-matched pair correlationCitation19,Citation20. All GLMMs specified a random intercept, an intercept term that randomly varied for each member. Furthermore, the models contained a group (restricted/unrestricted) by time period (2008/2009) interaction term which captured the DID effect. The GLMMs used to model medication utilization specified a logit link and binomial variance function, and analysis of cost data was performed specifying a log link and a gamma variance functionCitation20. The independent variables in the GLMMs were restricted plan status, time (2008 or 2009), age, gender, geographic region, plan type, diagnosis, and RxRisk-V score.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2/SAS Enterprise Guide 4.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The a-priori alpha level for all inferential analyses was set at 0.05.

Results

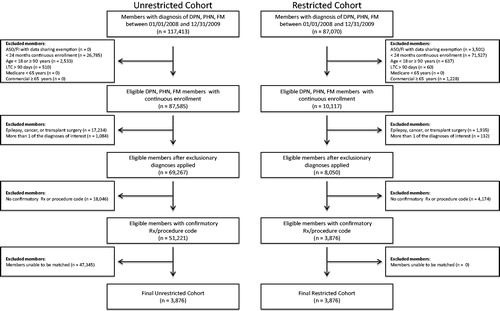

A total of 3876 members were identified in the restricted cohort and matched to 3876 members from the unrestricted cohort (). As shown in , both cohorts were primarily female (∼70%) and FM was the predominant diagnosis (84.7%). Members in the unrestricted cohort were older (mean = 49.0 years (SD = 10.4) vs 47.6 years (SD = 10.5); p < 0.001) and were characterized by a higher comorbidity burden (RxRisk-V score) relative to the restricted cohort, 5.4 (SD = 3.2) vs 4.4 (SD = 2.9) (p < 0.001) ().

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohorts.

In the restricted cohort, there was a greater decrease in the proportion of patients prescribed pregabalin, from 2008 (9.7%) to 2009 (5.0%), relative to the unrestricted cohort (from 15.0% to 12.9%). There was also a greater reduction in the number of pregabalin claims per member in the restricted cohort from 3.6 (SD = 3.9) to 2.3 (SD = 3.6), relative to the unrestricted cohort, from 2.8 (SD = 3.1) to 2.6 (SD = 3.3) (). These decreases resulted in DIDs of −2.6% (p = 0.008) and −1.1 (p < 0.001) for the members with claims and the number of claims, respectively, indicating that the greater reductions in the restricted cohort were statistically significant. The DID for overall gabapentin utilization was not statistically significant (DID = 1.8%, p = 0.080), nor were the DIDs associated with the other medication classes examined ().

Table 2. Unadjusted differences in prescription medication claims.*

Evaluation of the changes in healthcare resource utilization, unadjusted for covariates or potential risk factors, showed a significantly greater increase in use of all-cause physical therapy in the restricted cohort (DID 3.7%; p = 0.010) (). For disease-related healthcare resources, only the proportion of members with an outpatient visit showed a significant difference, with an increase in the restricted cohort (from 56.1% to 64.7%) relative to the unrestricted cohort (from 54.7% to 59.8%; DID = 3.6%, p = 0.022) (). The DIDs for all-cause outpatient, all-cause emergency room, all-cause inpatient, disease-related emergency room, disease-related inpatient, and disease-related physical therapy utilization were not statistically significant.

Table 3. Unadjusted differences in healthcare resource utilization.*

The year-over-year changes in unadjusted all-cause and disease-related total healthcare costs and component cost categories of medical costs and pharmacy costs were similar between the restricted and unrestricted cohorts, and DID analysis showed no significant between-cohort differences ().

Table 4. Unadjusted differences in healthcare costs.*

Results of conditional logistic regression for the post-index period indicated that restricted plan members were 2.4-times less likely to utilize pregabalin after the implementation of the step-edit policy compared with unrestricted plan members during the post-index period (odds ratio = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.36, 0.51; p < 0.0001) (). From 2008 to 2009 (i.e., changes from the pre- to post-index periods), the multivariate model of prescription utilization showed that the pregabalin step-edit restriction was associated with not only a net decrease in pregabalin use but also a net increase in gabapentin use (); the odds ratios were 0.04 (95% CI = 0.02, 0.08; p < 0.001) and 2.6 (95% CI = 1.72, 3.94; p < 0.001) for pregabalin and gabapentin use, respectively (both p < 0.001). There were also significant increases in the likelihood of prescribing of tricyclic antidepressants (OR = 2.44; 95% CI = 1.48, 4.00; p < 0.001), anaesthetic/lidocaine (OR = 2.26; 95% CI = 1.18, 4.34; p = 0.015), SNRIs (OR = 1.51; 95% CI = 1.06, 2.14; p < 0.001), and SSRIs (OR = 2.19; 95% CI = 1.42, 3.37; p = 0.022) in the restricted cohort relative to the unrestricted cohort ().

Table 5. Conditional logistic regression model of pregabalin use.

Table 6. Multiple regression analysis of medication utilization.

After adjusting for difference in demographic and clinical characteristics between the two groups, restricted plan membership was associated with a net increase in all-cause total medical costs ($1222; p = 0.016) and disease-related total healthcare costs ($859; p = 0.002) (). A marginally significant association was observed between the restricted plan and all-cause total healthcare costs ($1342; p = 0.054). No significant association was observed between the two plans with respect to disease-related medical costs and disease-related pharmacy costs.

Table 7. Multivariate model of all-cause and disease-related healthcare costs.

Discussion

Cost containment policies with the goal of limiting the use of specific medications and reducing pharmacy costs have been considered successful strategies in studies that have shown such policies reduce pharmacy costsCitation2–6. However, studies of step-therapy protocols for antidepressants and anti-hypertensives suggested that, while medication costs were reduced, total medical costs increasedCitation9,Citation10. A recent review of the impact of step-therapy interventions criticized those two studies for not also stratifying by disease-related costsCitation21. In contrast to those studies, the current analysis evaluated both disease-related and overall healthcare resource utilization and costs. Results from this study were consistent in the findings that there are no net savings in either disease-related or overall costs with initiation of a step-therapy protocol for pregabalin for the treatment of neuropathic pain associated with pDPN, PHN, or FM.

As expected, the step-therapy protocol was effective in decreasing the relative use of pregabalin, but also resulted in significant increases in the probability of patients using tricyclic antidepressants, SNRIs, SSRIs, and anaesthetic/lidocaine compared with the non-restrictive plan. Despite the significant reductions in pregabalin utilization in the restrictive plan, changes in all-cause and disease-related pharmacy costs, as well as all-cause and disease-related total medical costs, were similar between the step-therapy and the unrestricted plans.

The unrestricted cohort was characterized by a significantly higher age and comorbidity burden compared to the restricted cohort, and the compositional differences in the group may impact the results of unadjusted cost analysis. After adjusting for differences in age and comorbidity burden between the two groups, the restricted plan showed a significant net increase in all-cause total medical costs ($1222; p = 0.016) and disease-related total healthcare costs ($859; p = 0.002) relative to the unrestricted plan. These results suggest not only that there is not likely to be overall economic benefits associated with a pregabalin step-therapy policy for these conditions but also that, despite the reduction in pregabalin use, costs may be significantly higher than in the absence of such a policy. It should also be noted that, since the costs associated with administering the step-therapy protocol were not included, the estimated costs of the restrictive plan may be considered conservative.

This analysis also expands on a similar study that evaluated the impact of a prior authorization policy for pregabalin in the treatment of pDPN and PHN by including FM and providing a more detailed evaluation of resource utilization and costsCitation8. That study demonstrated no significant effects on pDPN- or PHN-specific medication or healthcare costs.

Of note, another study evaluating the impact of a pregabalin prior authorization policy in patients with pDPN and PHN in a Medicaid population reported significant increases in both unadjusted ($270; p < 0.01) and adjusted ($418; p < 0.01) disease-related medical costs with prior authorization relative to the unrestricted planCitation7. These increases, which differ from the similar costs observed in the two plans in the current analysis, may be due, at least in part, to the differences in the study populations. Although prior authorization and step-therapy represent diverse approaches to cost containment, the consistency of results among these studies, i.e., a reduction in pregabalin use without a significant net reduction in disease-related costs, is indicative of the need to focus patient management strategies as well as cost containment strategies on clinical outcomes rather than costs.

A strength of this study was our use of DID analysis, which is an appropriate and effective method for adjusting for baseline differences between the two plans that also enables comparison of relative differences over the time periods, thereby distinguishing the effects of the step-therapy protocol. The analysis of cost data in the current study was based on plan-specific costs, which were not standardized. Use of plan-specific costs may bias analysis of cost data; however, the DID approach mitigates concerns related to plan-specific cost data in that each member serves as their own comparison in the calculation of cost DID. A DID analysis may also represent a limitation since it accounts only for those observed changes that were parallel across the two plan types.

Another limitation of this study is that it focused on the use of pregabalin for the treatment of FM and neuropathic pain associated with pDPN and PHN. Pain severity, frequency, and chronicity are not captured in administrative claims data and were not measured in the current study. In addition, there are limitations to the use of ICD-9-CM codes to identify or quantify pain specific to these conditions. Consequently, we relied on pharmaceutical claims for medications commonly used to treat pain associated with these conditions for further identifying the patient population, under the assumption that these medications were being prescribed appropriately. However, as with most claims databases, there is an inherent inability to link the prescribing of a medication with the condition of interest, and therefore it is possible that these drugs were being prescribed for other conditions.

The combined analysis of pDPN, PHN, and FM also represents a limitation; since the majority of patients were diagnosed with FM (84.7%), the observed results may have been driven by this population. Thus, caution should be exercised when extrapolating these results to patients with pDPN and PHN. Lack of pain severity information, which is not available in administrative claims records and was not included in the present analysis, could influence type and extent of treatment and is acknowledged as a study limitation. In addition, while we adjusted for overall comorbidity burden, we did not measure or examine the impact of specific co-occurring conditions (e.g., depression) on study outcomes.

Finally, neither effectiveness nor safety outcomes resulting from the use of specific medications or the implementation of specific formulary policies are captured in claims data. Thus, like previous studies that have evaluated formulary management strategies, the design of this study did not enable assessment of pregabalin restriction on clinical outcomes; in the absence of studies evaluating the impact of these policies on patient health, the effects of such restriction policies on clinical outcomes has been questionedCitation21–23. Nevertheless, the data from the current study suggest that initiation of a step-therapy protocol, at least for pregabalin in the treatment of specific chronic and neuropathic pain conditions, may be of limited value in reducing healthcare costs.

Conclusions

In this commercial health plan population consisting predominantly of members diagnosed with FM, implementation of a pregabalin step-therapy protocol was associated with decreased pregabalin utilization. However, reduced use of pregabalin was not associated with net cost savings. While an unadjusted analysis showed that changes in all-cause and disease-related pharmacy costs, as well as all-cause and disease-related total medical costs, were similar between the two plans, an adjusted analysis suggested that there was a net increase in costs with pregabalin restriction; both all-cause total medical costs and disease-related total healthcare costs were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the restricted plan. These results suggest that a step-therapy restriction for pregabalin is unlikely to convey cost savings. Further studies are warranted to prospectively evaluate the economic impact of instituting restrictive medication management policies on clinical and patient-reported outcomes to enhance our understanding of the impact of these policies on the overall health and well-being of health plan members.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was conceived, funded, and carried out collaboratively by Humana Inc., Pfizer Inc., and Competitive Health Analytics, Inc. The research concept was approved by the Joint Research Governance Committee of the Humana-Pfizer Research Collaboration, comprised of Humana Inc. and Pfizer Inc. employees, and plans to publish results were made known prior to commencing the study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

BTS, AL, and NCP are employees of Competitive Health Analytics, a wholly owned subsidiary of Humana Inc., and are stockholders of Humana, Inc. Competitive Health Analytics, Inc. received funding support from Pfizer in connection with conducting this study and for the development of this manuscript. MU, AVJ, and JCC are employees and stockholders of Pfizer Inc. JME Peer Reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Editorial assistance was provided by E. Jay Bienen and was funded by Pfizer, Inc.

Previous presentation

Presented at the AMCP 2012 Educational Conference, Cincinnati, OH; held 3–5 October 2012.

References

- Pharmacy Benefit Management Institute. 2011–2012 Prescription Drug Benefit Cost and Plan Design Report. [online]. Plano, TX: Pharmacy Benefit Management Institute, LP, 2011. http://www.benefitdesignreport.com/. Accessed August 6, 2012

- Yokoyama K, Yang W, Preblick R, et al. Effects of a step-therapy program for angiotensin receptor blockers on antihypertensive medication utilization patterns and cost of drug therapy. J Manag Care Pharm 2007;13:235–44

- Dunn JD, Cannon E, Mitchell MP, et al. Utilization and drug cost outcomes of a step-therapy edit for generic antidepressants in an HMO in an integrated health system. J Manag Care Pharm 2006;12:294–302

- Lu CY, Law MR, Soumerai SB, et al. Impact of prior authorization on the use and costs of lipid-lowering medications among Michigan and Indiana dual enrollees in Medicaid and Medicare: results of a longitudinal, population-based study. Clin Ther 2011;33:135–44

- Law MR, Lu CY, Soumerai SB, et al. Impact of two Medicaid prior-authorization policies on antihypertensive use and costs among Michigan and Indiana residents dually enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare: results of a longitudinal, population-based study. Clin Ther 2010;32:729–41

- Motheral BR, Henderson R, Cox ER. Plan-sponsor savings and member experience with point-of-service prescription step therapy. Am J Manag Care 2004;10:457–564

- Margolis JM, Johnston SS, Chu BC, et al. Effects of a Medicaid prior authorization policy for pregabalin. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:e95–102

- Margolis JM, Cao Z, Onukwugha E, et al. Healthcare utilization and cost effects of prior authorization for pregabalin in commercial health plans. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:447–56

- Mark TL, Gibson TB, McGuigan KA. The effects of antihypertensive step-therapy protocols on pharmaceutical and medical utilization and expenditures. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:123–31

- Mark TL, Gibson TM, McGuigan K, et al. The effects of antidepressant step therapy protocols on pharmaceutical and medical utilization and expenditures. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:1202–9

- Lyrica® [pregabalin] capsules prescribing information. New York, NY: Pfizer, Inc., 2012

- Neurontin® [gabapentin] prescribing information. New York, NY: Pfizer, Inc., 2011

- Arnold LM, Goldenberg D, Stanford SB, et al. Gabapentin in the treatment of fibromyalgia. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:1336–44

- Backonja M, Beydoun A, Edwards KR, et al. Gabapentin for the symptomatic treatment of painful neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280:1831–6

- Fishman PA, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC, et al. Risk adjustment using automated ambulatory pharmacy data: the RxRisk model. Med Care 2003;41:84–99

- Sloan KL, Sales AE, Liu CF, et al. Construction and characteristics of the RxRisk-V: a VA-adapted pharmacy-based case-mix instrument. Med Care 2003;41:761–74

- Sales AE, Liu CF, Sloan KL, et al. Predicting costs of care using a pharmacy-based measure risk adjustment in a veteran population. Med Care 2003;41:753–60

- Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Logistic Regression. A Self-Learning Text. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 2010

- Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, et al. SAS® for Mixed Models. 2nd ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2006

- Vonesh EF. Generalized linear and nonlinear models for correlated data: theory and applications using SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2012

- Motheral BR. Pharmaceutical step-therapy interventions: a critical review of the literature. J Manag Care Pharm 2011;17:143–55

- Mackinnon NJ, Kumar R. Prior authorization programs: a critical review of the literature. J Manag Care Pharm 2001;7:297–302

- Shoemaker SJ, Pozniak A, Subramanian R, et al. Effect of 6 managed care pharmacy tools: a review of the literature. J Manag Care Pharm 2010;16:S3–20

- Duan N. Smearing estimate: a nonparametric retransformation method. J Am Stat Assoc 1983;78:605–10