Abstract

Objective:

Health resource utilization (HRU) and outcomes associated with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) are not well described. Therefore, a population-based cohort study was conducted to characterize patients hospitalized with AECOPD with regard to HRU, mortality, recurrence, and predictors of readmission with AECOPD.

Methods:

Using Danish healthcare databases, this study identified COPD patients with at least one AECOPD hospitalization between 2005–2009 in Northern Denmark. Hospitalized AECOPD patients’ HRU, in-hospital mortality, 30-day, 60-day, 90-day, and 180-day post-discharge mortality and recurrence risk, and predictors of readmission with AECOPD in the year following study inclusion were characterized.

Results:

This study observed 6612 AECOPD hospitalizations among 3176 prevalent COPD patients. Among all AECOPD hospitalizations, median length of stay was 6 days (interquartile range [IQR] 3–9 days); 5 days (IQR 3–9) among those without ICU stay and 11 days (IQR 7–20) among the 8.6% admitted to the ICU. Mechanical ventilation was provided to 193 (2.9%) and non-invasive ventilation to 479 (7.2%) admitted patients. In-hospital mortality was 5.6%. Post-discharge mortality was 4.2%, 7.8%, 10.5%, and 17.4% at 30, 60, 90, and 180 days, respectively. Mortality and readmission risk increased with each AECOPD hospitalization experienced in the first year of follow-up. Readmission at least twice in the first year of follow-up was observed among 286 (9.0%) COPD patients and was related to increasing age, male gender, obesity, asthma, osteoporosis, depression, myocardial infarction, diabetes I and II, any malignancy, and hospitalization with AECOPD or COPD in the prior year.

Limitations:

The study included only hospitalized AECOPD patients among prevalent COPD patients. Furthermore, information was lacking on clinical variables.

Conclusion:

These findings indicate that AECOPD hospitalizations are associated with substantial mortality and risk of recurrence.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is recognized clinically as a chronic persistent airflow limitation associated with airway inflammationCitation1. An acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD), defined as an acute and sustained worsening of the patient’s condition beyond normal day-to-day variations and requiring medical intervention, is a common complication of COPDCitation1–3. The number of AECOPD per year has been estimated to be between 0.6–3.5 per patient depending on disease severity and ageCitation4. Various factors such as respiratory infections, exposure to industrial pollutants, and cold weather are associated with AECOPDCitation1,Citation2. AECOPD may require hospitalization and, in severe cases, admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) and non-invasive or mechanical ventilation, thereby producing considerable healthcare economic burdenCitation1,Citation2,Citation4,Citation5. In fact, AECOPD constitutes the highest direct cost in the treatment of COPDCitation2. Nevertheless, characteristics of hospitalized AECOPD patients, including health resource utilization (HRU) and outcomes, are not well describedCitation6.

We, therefore, aimed to characterize patients hospitalized with AECOPD, and to examine associated HRU, patterns of mortality and recurrence, and predictors of readmission with AECOPD in the following year.

Patients and methods

Setting and design

Denmark has a long tradition of continuous registration of high-quality medical data, which makes it a unique setting for conducting registry-based studiesCitation7–9. Furthermore, a tax-supported healthcare plan guarantees universal medical care for all Danish residents and partial reimbursement for prescribed medicationsCitation7.

This cohort study was conducted in northern Denmark, which covers a population of ∼1.8 million (30% of the Danish population)Citation7. The study period January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2009 was chosen because of the availability of intensive care data. A unique personal identifier assigned to all Danish residents allowed linkage of the medical registriesCitation9, which are described below.

Data sources

The Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) provides information on all inpatient admissions to hospitals since 1977, and all outpatient clinic and emergency room visits since 1995Citation8. In the DNPR, each admission is registered by one primary diagnosis and up to 19 secondary diagnoses classified according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) since 1994Citation8. Information on intensive care treatment is also included in the DNPR.

Information on prescriptions is recorded in the Prescription Databases of the Central and North Denmark RegionsCitation7. This database records the patient’s personal identifier, dispensing date, and the type and quantity of drug prescribed (according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System) each time a prescription is redeemed at the pharmacyCitation7.

The Civil Registration System holds information on date of birth, gender, vital status, and country of origin, among other variables, for all individuals legally residing in Denmark at any time since 1968Citation9. It allows for complete follow-up of all residents of Denmark.

All ICD and ATC codes used in the present study can be found in the Supplementary Appendix (eTable 1).

Study subjects

We used the DNPR to identify all patients with COPD diagnosed between 1977–2005 who had one or more AECOPD hospitalizations between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2009. We defined COPD as a primary in- or outpatient diagnosis of either (a) simple and mucopurulent chronic bronchitis, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or COPD, or (b) respiratory failure with a secondary in- or outpatient diagnosis of simple and mucopurulent chronic bronchitis, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or COPD. Patients were regarded as having experienced an AECOPD hospitalization if they had a primary inpatient diagnosis of AECOPD, or a primary diagnosis of respiratory failure or acute respiratory infection with a secondary diagnosis of AECOPD. We used these broad definitions of COPD and AECOPD hospitalizations because the use of more restrictive primary discharge diagnoses may have resulted in an incomplete sampleCitation10,Citation11.

We excluded patients who were younger than 40 years at the start of the study period given the low COPD prevalence in this patient groupCitation12 and the potential risk of misclassification of asthma as COPD. Also, we excluded emergency room admissions as COPD is rarely treated in this setting in Denmark. In this context, it should be noted that patients referred to a specialized ward after an emergency room admission would be coded as inpatient admission and thereby included in the cohort.

Characteristics of hospitalized AECOPD patients and their health resource utilization

We retrieved information on the following variables to describe hospitalized AECOPD patients and their HRU and outcomes: (1) demographic variables, including age and gender; (2) comorbidities within 5 years before the AECOPD hospitalization as defined by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)Citation13,Citation14, and, also, alcoholism-related diseases, atrial fibrillation/flutter, medically diagnosed obesity, lung cancer, asthma, hypertension, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, depression, and venous thromboembolism; (3) hospitalization length of stay (LOS); (4) mechanical ventilation (MV) use; (5) non-invasive ventilation (NIV) use; (6) AECOPD recurrence rate by days 30, 60, 90, and 180, with recurrence defined as readmission (inpatient or outpatient), mechanical ventilation, or simultaneous antibiotic and steroid prescription; (7) mortality in-hospital and by days 30, 60, 90, and 180 post-discharge; (8) number of exacerbations in the year before study inclusion, and (9) the seasonality of AECOPD hospitalizations.

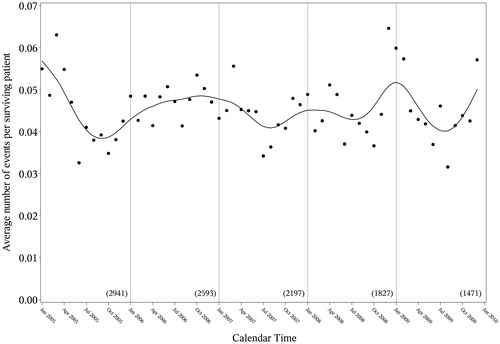

Statistical analysis

The primary statistical analyses consisted of four parts. First, we characterized patients hospitalized with AECOPD overall and stratified by whether they had been hospitalized in the prior year. We calculated the means, standard deviations (SDs), medians, interquartile ranges, totals, and percentages for relevant characteristics. Second, we described the HRU, recurrence frequency, and mortality for AECOPD hospitalizations overall. Patients receiving both NIV and MV use were included in both categories. Third, we characterized each AECOPD hospitalization event (i.e., the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th event) in the first 12 months of the study period (i.e., year 2005). The analyses of recurrence were restricted to hospital survivors. Fourth, we plotted the seasonality of the number of AECOPD hospitalizations per surviving patient (1) for the overall period and (2) by month with all years combined. For graphical visualization, we fitted a cubic spline to the data. In a secondary analysis, we used multivariate logistic regression to examine the predictors of readmission for AECOPD at least once and at least twice in the year following study inclusion. This secondary analysis included only persons surviving at least 12 months after their AECOPD. We also performed two post-hoc analyses. First, to address potential misclassification of asthma, we stratified the results for HRU, recurrence frequency and mortality associated with AECOPD hospitalizations by any previous diagnosis of asthma. Second, we addressed the potential impact of comorbidity by repeating the analysis after disaggregating the cohort according to CCI score group (0, 1, 2, or 3+).

All analyses were performed in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. As this study did not involve any contact with patients or any intervention, it was not necessary to obtain permission from the Danish Scientific Ethical Committee.

Results

Characteristics of patients hospitalized with AECOPD

We identified 3176 hospitalized AECOPD patients, among whom 663 (20.9%) had experienced AECOPD hospitalization in the year before study inclusion (). Median age was 72.1 years at study inclusion (interquartile range [IQR] = 65.2–77.7 years) and 55.2% were female.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for patients hospitalized with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) in the study period, by hospitalization in the year before study inclusion, Denmark, 2005–2009.

Women constituted a smaller proportion (51.7%) of patients hospitalized with AECOPD in the year before study inclusion compared with patients with no AECOPD hospitalization in the year before inclusion (56.1%). In addition, patients hospitalized with AECOPD in the previous year had more comorbidity, largely because of a higher prevalence of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, atrial fibrillation/flutter, asthma, and osteoporosis.

Health resource utilization, recurrence rates, and mortality rates for AECOPD hospitalizations

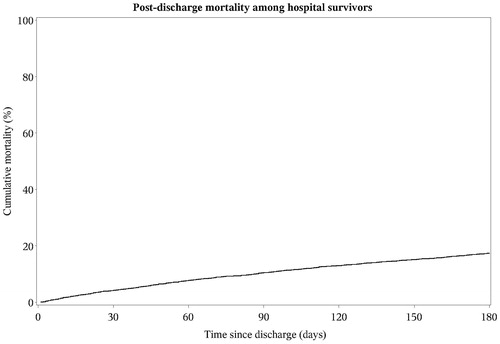

In total, we observed 6612 AECOPD hospitalizations among the 3176 patients during the study period. shows the HRU, recurrence rate, and mortality rate associated with these hospitalizations. The median LOS for AECOPD hospitalizations was 6 days (IQR = 3–9 days). Those who were admitted to the ICU had a median LOS of 11 days (IQR = 7–20 days), whereas those without an ICU stay had a median LOS of 5 days (IQR = 3–9 days). For all hospitalizations, MV and NIV were provided in 193 (2.9%) and 479 (7.2%), respectively. In-hospital mortality was 5.6% and post-discharge mortality increased from 4.2% at 30 days to 17.4% at 180 days after discharge (, ). Similarly, recurrence measured as the proportion of patients with readmission, MV use, or simultaneous antibiotics and steroid prescription, increased steadily from 30 to 180 days after discharge.

Figure 1. Post-discharge mortality following hospitalizations for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Denmark, 2005–2009.

Table 2. Health resource utilization (HRU), recurrence rate, and mortality rate for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) hospitalizations, Denmark, 2005–2009.

Characteristics of each AECOPD hospitalization

provides the characteristics of AECOPD hospitalizations in 2005. As patients experienced more AECOPD hospitalizations, the time between subsequent hospitalizations decreased. The LOS was largely independent of the number of AECOPD hospitalization events, as were the frequency of ICU admissions, MV and NIV use, in-hospital mortality, and simultaneous antibiotic/steroid prescriptions. However, 30-day, 60-day, 90-day, and 180-day readmission and overall mortality generally increased with the number of AECOPD events in the 12-month period following study inclusion.

Table 3. Characteristics of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) hospitalization events in the first 12 months of follow-up (2001 patients did not have an AECOPD in 2005).

Seasonality

The number of AECOPD hospitalizations per surviving patient over the entire study period is shown with a fitted spline in . The data follows a general trend in which the number of AECOPD hospitalizations peaks in the winter and decreases to its minimum during the summer. The exception to this general trend is 2006, during which the AECOPD hospitalization rate remained high throughout the year. When the AECOPD hospitalization data are presented by month only with a spline applied, the seasonal pattern becomes even more apparent with a clear trough in the number of AECOPD hospitalization events during the summer months (Supplementary Appendix, eFigure 1).

Secondary analyses

Among the 3176 COPD patients hospitalized with AECOPD, 1175 (37.0%) were admitted to the hospital for an AECOPD at least once and 286 (9.0%) were admitted at least twice in the first study year. Predictors of having at least one or at least two AECOPD hospitalizations in the 12-month period following study inclusion are presented in . Age, obesity, asthma, osteoporosis, depression, and hospitalization with AECOPD in the prior year predicted a substantial risk of having at least one admission with AECOPD. In addition, male gender, myocardial infarction, diabetes I and II, and any malignancy predicted a higher odds of having at least two AECOPD hospitalizations in the 12-month period. Hospitalization with COPD in the prior year was a strong predictor of at least one hospitalization in the subsequent year (OR = 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.4, 2.3), but not of two or more hospitalizations (OR = 1.2, 95% CI = 0.6, 2.6).

Table 4. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for predictors of hospitalization for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD).a

Restriction to patients without any previous asthma diagnosis revealed estimates similar to those for AECOPD hospitalizations overall (Supplementary Appendix, eTable2). Mortality was higher and readmission rate was lower among patients without previous asthma diagnosis compared with those without. LOS, and MV and NIV use was similar. Patients with increased comorbidity level had higher mortality and readmission rate, but LOS and use of MV and NIV was similar to patients with low comorbidity level (Supplementary Appendix, eTable 2). Stratification of the results for each AECOPD hospitalization event by presence or absence of previous asthma diagnosis and CCI score group was inconclusive because of small numbers (Supplementary Appendix, eTables 3–8).

Discussion

In this population-based Danish cohort study, we describe the characteristics and AECOPD-related outcomes of prevalent COPD patients identified in 2005 and hospitalized for AECOPD between 2005–2009. We observed a high prevalence of comorbidities, especially among patients who had experienced AECOPD in the prior year. Mortality and readmission frequency for AECOPD was high and generally increased with each AECOPD hospitalization, whereas other HRU variables were largely independent of the number of AECOPD hospitalizations.

It is important to note that our results may apply only to AECOPD requiring hospitalization (moderate-to-severe cases) because mild cases of AECOPD are not always seen in the hospital settingCitation15. Another limitation of our study is that we have no clinical data on the length of each exacerbation, which makes it difficult to differentiate between recurrent and relapsing eventsCitation1,Citation15. However, the majority of patients recover within 30 days after AECOPD onsetCitation1. In our data, the mean times between AECOPD hospitalizations were between 44–81 days, which supports that they are in fact recurrent events.

It is known that exacerbations of COPD are more frequent during the winter than summer monthsCitation15. Hence, the fact that our data largely showed the same trend further confirms the validity of our results. Why our data did not follow the trend in 2006 is hard to explain. Weather is unlikely to be an important factor, since weather reports from the Danish Meteorological Institute show that the mean temperature, precipitation, and hours of sunshine were not substantially different in the summer of 2006 compared with the rest of the study periodCitation16. Similarly, reports of influenza activity during the study period do not explain the patternCitation17. Differences in pollen concentrations may contribute to the aberrant 2006 pattern, because relatively high levels of elm, birch, Alternaria, and Cladosporium were reported in 2006Citation1Citation8.

Previous studies on HRU among AECOPD patients are sparse and only a few have investigated factors associated with readmissionCitation6,Citation19,Citation20. An important strength of our study is the setting (i.e., population-based study in a country with equal access to a uniform healthcare system), which allowed us to investigate a broad patient group. Previous studies have focused primarily on specific sub-groups of AECOPD patients such as males or patients admitted to an emergency department or ICUCitation19,Citation21–25. Furthermore, the high validity of the data in the registries assured little influence from information and selection biasesCitation7–9,Citation14. We cannot rule out that some degree of misdiagnosis between asthma and COPD may have occurred. We aimed to mitigate such an effect by including only individuals aged 40 years or more, in whom new diagnoses of asthma are uncommon. Any information bias should therefore be minimal, as confirmed by very similar results when restricting to patients without a history of asthma. Of note, it is interesting that we found lower mortality but a higher readmission rate, among the hospitalized COPD patients who also had asthma. Previous studies of the asthma-COPD overlap have reported more severe disease, health-related quality-of-life, and greater consumption of healthcare resources in this groupCitation26,Citation27. However, reports are conflicting with regard to mortalityCitation28.

Our study confirms and extends a previous study of 300 patients hospitalized with AECOPD at three medical wards on Zealand, Denmark, in which in-hospital mortality, 30-day mortality, frequency of readmission, ICU stay, MV use, and NIV use were all nearly identicalCitation29. However, international differences seem to exist with regard to frequency of MV and NIV useCitation30. For example, among all AECOPD admissions to ∼1000 US hospitals during 2008, 4.5% were treated with NIV and 3.5% with MVCitation30. Differences in guidelines for respiratory support modalities or severity of AECOPD in the study populations may possibly explain why NIV is more frequently used for treatment of AECOPD in Denmark. The frequent use of NIV in our study may in turn explain the low degree of MV use, since NIV use reduces the need for MVCitation30.

Compared with previous studies, the comorbidity burden was lower in our study, primarily because of lower prevalence of cardiovascular diseases (e.g., myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and hypertension), diabetes mellitus, dementia, and depressionCitation2,Citation5,Citation19,Citation20,Citation25,Citation31,Citation32. Most striking, comorbidities were more prevalent in the study by Ranieri et al.Citation31. However, their study population was, on average, 11 years older than oursCitation31. Similarly, the study by Almagro et al.Citation20 included 90% men. Thus, the discrepancies found are probably due to differences in source population, such as severity, age, and gender distributionCitation2,Citation19,Citation20,Citation25,Citation31,Citation32.

Compared with previous studies, we found relatively low mortality and readmission frequencies. Previous studies report an in-hospital mortality of 4–30% with highest mortality among patients with respiratory failure and patients admitted to specialist respiratory wards or the ICUCitation2,Citation3,Citation5,Citation15. A similar pattern of variation between patient groups has previously been observed for mortality at 30 days, 60 days, 90 days, and 180 days, which is ∼5%, 9–20%, 11–41% (except 4.5% in a study by Almagro et al.Citation20), and 13–47%, respectivelyCitation2,Citation3,Citation15,Citation20. Readmission frequency at 90 days and 180 days is ∼20–38% and 50%Citation3,Citation20.

Previous studies show that patients with a recent history of AECOPD have a worse prognosis than patients without such a history, although methodological differences and limitations make comparison between studies difficultCitation19,Citation25,Citation32–37. Most recently, Suissa et al.Citation38 examined the effect of the number of AECOPD hospitalizations on mortality and readmission rate. They found that the median time between successive AECOPD events decreased with each successive exacerbationCitation38. The mortality rate and the readmission rate increased with every new eventCitation38. In our study, we observed the same patterns for mortality and readmission risk, although neither increased after the fourth AECOPD hospitalization. However, an important limitation of our study, compared with the previous one, is that we considered a prevalent cohort. Hence, the first AECOPD hospitalization during our study period is not necessarily the first-ever AECOPD hospitalization, potentially resulting in a mix of patients who are at different stages in their disease progression. Nevertheless, these findings may reflect a vicious circle where frequent exacerbations accelerate the decline in lung function causing disease progression, which in turn increases AECOPD frequency and eventually leads to deathCitation2,Citation15,Citation37.

The LOS in our study population (median = 6, IQR = 3–9 days) is slightly shorter than reported by previous studies (mean = 5–12 daysCitation5,Citation15,Citation19,Citation20,Citation24,Citation31,Citation34,Citation39,Citation40; median LOS 4–10 daysCitation5,Citation10,Citation21,Citation41,Citation42). Short LOS is not necessarily a marker of effective treatment, as it may instead be associated with poor outcomes such as high risk of readmissionCitation1,Citation3,Citation34. However, we feel certain that this is not the case, since the mortality and readmission frequency in our study is similar to, or even lower than, those reported in previous studiesCitation2,Citation3,Citation15. Furthermore, our study included a broader population of AECOPD patients than the majority of previous studies.

Our results confirm those of others with regard to age, male gender, cardiac comorbidities, and asthma as risk factors for readmission with AECOPDCitation2,Citation6,Citation19. The prevalence of depression is high among patients with severe COPD, and AECOPD negatively affects health-related quality-of-life, especially in the case of treatment failureCitation2,Citation3. We therefore reason that frequent AECOPD results in, rather than from, depressionCitation3, causing the positive association demonstrated in our study. On the other hand, some studies have observed the opposite association, which may reflect poor health-seeking behavior among depressed patientsCitation6. Clinical variables such as severe FEV1 impairment, chronic bronchial mucus hypersecretion, daily cough and wheeze, and persistent symptoms of chronic bronchitis may also be risk factors for readmission with AECOPDCitation2,Citation3,Citation6,Citation20. Unfortunately, we lacked information on these.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that mortality and risk of readmission is high among patients hospitalized with AECOPD and increases with the number of AECOPD admissions. Readmission is frequent and can be predicted by age, gender, and presence of comorbidities, especially cardiovascular disease, asthma, osteoporosis, and depression. Prevention of exacerbations should, therefore, be an important goal in the improvement of health outcomes such as mortality, the number of readmissions, and healthcare costs associated with COPD.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The study received funding from the Clinical Epidemiological Research Foundation and by a grant from MedImmune LLC.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

XX and JMP are employed at MedImmune LLC. JPF and NAM are former employees of MedImmune, LLC. None of the other authors have received fees, honoraria, grants or consultancy fees related to the topic.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (359.2 KB)References

- Burge S, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations: definitions and classifications. Eur Respir J 2003;21(41 Suppl):46s-53s

- Anzueto A. Impact of exacerbations on COPD. Eur Respir Rev 2010;19:113-8

- Tan WC. Factors associated with outcomes of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD 2004;1:225-47

- Atsou K, Chouaid C, Hejblum G. Variability of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease key epidemiological data in Europe: systematic review. BMC Med 2011;9:7

- Perera PN, Armstrong EP, Sherrill DL, et al. Acute exacerbations of COPD in the United States: inpatient burden and predictors of costs and mortality. COPD 2012;9:131-41

- Steer J, Gibson GJ, Bourke SC. Predicting outcomes following hospitalization for acute exacerbations of COPD. QJM 2010;103:817-29

- Ehrenstein V, Antonsen S, Pedersen L. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: Aarhus University Prescription Database. Clin Epidemiol 2010;2:273-9

- Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):30-3

- Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):22-5

- Connors AFJ, Dawson NV, Thomas C, et al. Outcomes following acute exacerbation of severe chronic obstructive lung disease. The SUPPORT investigators (Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:959-67

- Thomsen RW, Lange P, Hellquist B, et al. Validity and underrecording of diagnosis of COPD in the Danish National Patient Registry. Respir Med 2011;105:1063-8

- Littner MR. In the clinic. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:ITC4-1–ITC4-15; quiz ITC4-6.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-83

- Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, et al. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:83

- Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations. 1: Epidemiology. Thorax 2006;61:164-8

- The Danish Meteorological Institute. Danish weather since 1874 - month by month with temperatur, precipitation, and hours of sunshine, as well as descriptions of the weather - with English translations. The Danish Meteorological Institute: Copenhagen, 2011; http://www.dmi.dk/dmi/tr11-02.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2012

- Statens Serum Institut (SSI). EPI-NEWS. About diseases and vaccines. Statens Serum Institut (SSI): Copenhagen, http://www.ssi.dk/Aktuelt/Nyhedsbreve/EPI-NYT.aspx. Accessed November 9, 2012

- The Danish Meteorological Institute. Pollen concentrations. Archive data. The Danish Meteorological Institute: Copenhagen. http://www.dmi.dk/dmi/index/viden/pollen/pollenoversigt-2012-grafer-arkiv.htm. Accessed June 21, 2012

- McGhan R, Radcliff T, Fish R, et al. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Chest 2007;132:1748-55

- Almagro P, Cabrera FJ, Diez J, et al. Working Group on COPD of the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine. Comorbidities and short-term prognosis in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation of COPD. The EPOC en Servicios de medicina interna (ESMI) study. Chest 2012;142:1126-33

- Ai-Ping C, Lee KH, Lim TK. In-hospital and 5-year mortality of patients treated in the ICU for acute exacerbation of COPD: a retrospective study. Chest 2005;128:518-24

- Breen D, Churches T, Hawker F, et al. Acute respiratory failure secondary to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated in the intensive care unit: a long term follow up study. Thorax 2002;57:29-33

- Chung LP, Winship P, Phung S, et al. Five-year outcome in COPD patients after their first episode of acute exacerbation treated with non-invasive ventilation. Respirology 2010;15:1084-91

- Fruchter O, Yigla M. Predictors of long-term survival in elderly patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology 2008;13:851-5

- Kim S, Clark S, Camargo CA. Mortality after an emergency department visit for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD 2006;3:75-81

- Andersén H, Lampela P, Nevanlinna A, et al. High hospital burden in overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD. Clin Respir J 2013; Epub 2013/02/01.

- Zeki AA, Schivo M, Chan A, et al. The Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome: a common clinical problem in the elderly. J Allergy 2011;2011:861926

- Mannino DM. COPD: epidemiology, prevalence, morbidity and mortality, and disease heterogeneity. Chest 2002;121(5 Suppl):121S-6S

- Eriksen N, Hansen EF, Munch EP, et al. [Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Admission, course and prognosis]. Ugeskr Laeger 2003;164:3499-502

- Chandra D, Stamm JA, Taylor B, et al. Outcomes of noninvasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the United States, 1998-2008. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:152-9

- Ranieri P, Bianchetti A, Margiotta A, et al. Predictors of 6-month mortality in elderly patients with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease discharged from a medical ward after acute nonacidotic exacerbation. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:909-13

- Soler-Cataluna JJ, Martinez-Garcia MA, Roman Sanchez P, et al. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2005;60:925-31

- Almagro P, Calbo E, Ochoa de Echagüen A, et al. Mortality after hospitalization for COPD. Chest 2002;121:1441-8

- Dransfield MT, Rowe SM, Johnson JE, et al. Use of beta blockers and the risk of death in hospitalised patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Thorax 2008;63:301-5

- Faustini A, Marino C, D'Ippoliti D, et al. The impact on risk-factor analysis of different mortality outcomes in COPD patients. Eur Respir J 2008;32:629-36

- Roche N, Zureik M, Soussan D, et al. Predictors of outcomes in COPD exacerbation cases presenting to the emergency department. Eur Respir J 2008;32:953-61

- Halpin DM, Decramer M, Celli B, et al. Exacerbation frequency and course of COPD. Int J COPD 2012;7:653-61

- Suissa S, Dell'Aniello S, Ernst P. Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax 2012; 67: 957--63

- Gunen H, Hacievliyagil SS, Kosar F, et al. Factors affecting survival of hospitalised patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2005;26:234-41

- Liaaen ED, Henriksen AH, Stenfors N. A Scandinavian audit of hospitalizations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2010;104:1304-9

- Patil SP, Krishnan JA, Lechtzin N, et al. In-hospital mortality following acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1180-6

- Wang Q, Bourbeau J. Outcomes and health-related quality of life following hospitalization for an acute exacerbation of COPD. Respirology 2005;10:334-40