Abstract

Objective:

Most incidences of basal cell carcinoma are cured by a number of surgical or non-surgical treatments. However, a few patients have lesions which have metastasized or progressed to an extent that surgery or other treatment options are not possible. The lesions associated with advanced basal cell carcinoma (aBCC) can be disfiguring, affecting patients’ psychological state, general quality-of-life (QoL), and potentially life expectancy. The objective of this study was to capture societal utility values for health states related to aBCC, using the time trade-off (TTO) methodology.

Methods:

Nine health states were developed with input from expert clinicians and literature. States included: complete response (CR), post-surgical, partial response (PR) (with differing sized lesions [2 or 6 cm]), stable disease (SD) (with differing size and number of lesions [2 or 6 cm, or multiple 2 cm]) and progressive disease (PD) (with differing sized lesions [2 or 6 cm]). A representative sample of 100 members of the UK general public participated in the valuation exercise. The TTO method was used to derive utility values based upon subjects’ responses to decision scenarios; between living in the health state for 10 years or living in a state of full health for 10-x years.

Results:

Mean utility scores were calculated for each state. The least burdensome state as valued by subjects was CR (mean = 0.94; SD = 0.08), suggesting only a minimal impact on QoL. The state valued as having a greatest impact on QoL was PD, with a 6 cm lesion (mean = 0.67, SD = 0.25).

Limitations and conclusions:

Not all possible presentations of aBCC were included; the disease is a challenging condition to characterise given its rarity, the nature of the patients affected, and its variable progression. Findings suggest that aBCC is associated with significant burden for individuals, even when their disease is stable or where surgical treatment has been successful.

Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is a type of non-melanoma skin cancer, which has the highest incidence of all cancers in white populationsCitation1. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignant tumour of the skin in humansCitation2, accounting for ∼2 million cases per year with prevalence increasingCitation3–6. Although surgery and a number of other treatment modalities can cure most cases of BCC, a minority of patients experience progression to life-threatening, unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic tumoursCitation7. In Europe, aBCC is encountered at a rate of 1–2% and progression to a metastatic form is extremely rare (0.0028–0.55% of BCC)Citation4,Citation8. The lesions and scarring associated with advanced basal cell carcinoma (aBCC) can be extremely disfiguring; in many cases, the head and neck are the anatomical areas most greatly affected, with facial structures including the eyes and nose commonly involvedCitation4. As such, aBCC will almost certainly affect patients’ psychological state and general quality-of-life (QoL). Further, given that these patients tend to present a psychologically abnormal behaviour to begin withCitation4, their underlying ability to self-assess QoL may often be questionable. In reality, however, there have been very few studies investigating both how, and to what extent, QoL is affected in aBCC patients; the majority of existing literature focuses on single patient case studies, or is not specific to the advanced form of the disease.

As new treatments for aBCC emerge, their benefits for patients will be assessed by decision-makers. The collection of health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) data is an important consideration for healthcare decision-makers, such as the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) in the UK. Any new treatment is reviewed in terms of its clinical and cost effectiveness. Treatment benefits can be assessed in terms of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), which represent the product of survival and QoL. Quality-of-life must be expressed as a preference weighted index, known as a utility value, preferably using EQ-5DCitation9.

One method that can be used to derive utilities involves the use of vignette descriptions of health states which are valued by patients or members of the general public. A vignette study entails the development of health state descriptions (vignettes) which describe states of health for a specific disease, such as complete response. These vignettes are then evaluated by members of the general public in a valuation exercise using stated preference methods such as the standard gamble or time trade-off (TTO). In the UK, the TTO method is preferred by NICECitation9. There are several steps that can be taken to maximize the quality of the vignette methodology. The first is to undertake in-depth qualitative interviews with expert clinicians, and ideally patients with the condition, as a basis for developing the content of the health states. The vignettes should include information relating to the different dimensions of QoL (e.g., physical functioning, psychological health) rather than simply focusing on specific symptoms of the condition being measured. The descriptive system of the EQ-5D is a useful framework for allowing this. Research also suggests that face-to-face interviews for health state valuation is the most robust method for capturing TTO data, in comparison to other methods, such as online data collectionCitation10.

No utility values currently exist for health states associated with aBCC, making the impact on HRQoL difficult to assess. The objective of this study, therefore, was to capture societal utility values for health states related to aBCC, using the TTO methodology.

Patients and methods

In order to collect utility values from members of the UK general public, health state vignettes associated with various stages of aBCC and treatment response were developed for use in a valuation exercise.

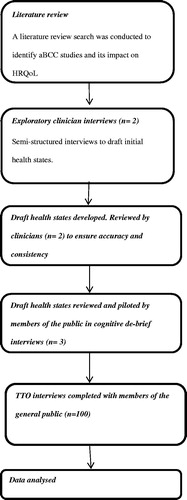

An overview of the methodology is outlined in .

Development of health state vignettes

Literature review

A review of the literature was conducted to identify studies that contained information, particularly qualitative, on how aBCC affects patients’ HRQoL. Through a structured search only a limited number of articles were identified (n = 16), and only three of these articles were deemed relevant to include for full reviewCitation11–13. These three articles were selected following abstract review as they appeared to contain qualitative information pertaining to the impact of aBCC on patients’ quality-of-life and disease presentation. A majority of the recovered papers failed to describe and assess the disease burden to patients, focusing rather on how to medically treat advanced forms of the disease. Of the three articles that did provide information, two were case studies focusing on one single patientCitation11,Citation13. The third paper, by Lear et al.Citation12, describes a utility study (using standard gamble) for basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Each patient (n = 4 1) was presented with two clinical scenarios; the first involving a primary BCC on the nose, the second involving a primary squamous cell carcinoma on the lip. The study results suggested that the lesions produced a very minimal impact on quality-of-life with mean utility values of 0.99 (on a scale from 0, dead to 1.0, full health). However, these results are only of limited use because they do not describe an advanced stage of disease. The general paucity of literature regarding QoL in aBCC patients could be due to the rarity of the disease.

The findings from the literature review were used as the basis for the development of a discussion guide for use in interviews with clinicians and to inform the development of the draft health state descriptions.

Clinician interviews

Two expert dermatologists with experience of working with patients with BCC and aBCC were interviewed in the development of the health states. Both were selected for their high level of expertise within this clinical area, and both are affiliated to hospitals and clinical practice within the UK (Manchester and Portsmouth). The interviews were informed by a discussion guide and the experts were questioned in detail to explore how living with aBCC at differing stages of treatment response would impact on patients’ HRQoL. Information on how patient functioning was affected in each of the EQ-5D domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) was sought, as well as any other information thought to be relevant to patients with aBCC.

Both clinicians consulted found it difficult to characterize a ‘typical’ patient due to the degree of heterogeneity in both presentation and patient characteristics associated with aBCC, and the low number of patients that they had seen. Both clinicians described that the point at which BCC becomes advanced is somewhat subjective, because some surgeons are more willing to attempt surgery than others. Generally, it is at a point where surgery is no longer an option, either because it is not appropriate (due to multiple recurrences or likely significant disfigurement or deformity) or because surgery is contraindicated. There does not appear to be a clear definition in terms of tumour size; mainly because the importance and definition of size will vary depending upon anatomical location. Patients were described as typically older than non-advanced BCC patients, perhaps because younger patients were thought to be more likely to seek medical advice earlier. Older patients are also more likely to have received previous treatment for recurrent lesions leading to potentially unresectable tumours. The length of time it takes for the disease to progress to the advanced form also means that these patients will inevitably be older.

Other than the skin lesions themselves, few other noticeable symptoms were described by the clinicians. The emotional impact of living with lesions means that many patients become embarrassed, either from the dressings or the lesions themselves. The clinicians described how the lesions can weep or bleed, and have the potential to become infected, which can cause them to smell. The clinicians reported that a number of these patients tend to isolate themselves, and, although physically they could work, many either choose not to or are retired. For a variety of reasons, social isolation was cited as the most common reason for aBCC patients to not lead a normal life. It was suggested that this, in turn, results in patients becoming anxious and depressed.

Furthermore, clinicians reported that the most common site for an aBCC lesion is the head or neck: because these areas are the hardest to operate on. Size of lesions vary greatly, and ultimately depend upon subjective quantification; a 3 cm lesion on the nose could be thought of as reasonably large, but a 3 cm lesion on the scalp would not necessarily be classed as large. The clinicians reported that, from their experience, the majority of lesions are between 2–5 cm, with a large lesion generally between 7–10 cm.

Health state validation

From the information gained during the literature review and the clinician interviews, nine draft health state vignettes were initially developed. The vignettes depicted how a patient with aBCC may present at a given point in time. Validity and suitability of the states was then sought before their inclusion in the valuation exercise. Two expert clinicians (one involved in the development stage and one who had not been previously involved, to provide a fresh perspective) were asked to review the states for accuracy and clinical validity in their depiction of HRQoL for patients with aBCC.

The health states underwent cognitive debriefing and piloting with three members of the general public to assess their interpretation and understanding of the concepts and wording. The states were found to be readily comprehensible and were deemed suitable for use in a valuation exercise with the general public.

Following the validation process of the nine draft states, the final nine health state vignettes developed and used in the valuation exercise were:

Complete response (CR);

Post-surgical state;

Partial response (PR) with small growth (2 cm);

PR with large growth (6 cm);

Stable disease (SD) with small growth (2 cm);

SD with multiple growths (at 2 cm);

SD with large growth (6 cm);

Progressed disease (PD) with small growth (2 cm); and

PD with large growth (6 cm).

Main study

A broadly representative sample of 100 members of the UK general public was recruited to participate in the final valuation exercise to elicit utility values for the nine aBCC health states. All participants had to be 18 years of age or older, reside in the UK, and be able to provide written informed consent.

Participants were recruited with the intent of matching UK demographic census dataCitation14. Five experienced field interviewers (trained research assistants) based in different locations around the UK (Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, London, Dunblane, and Bolton) undertook the TTO interviewing which aimed to collect data from 100 participants. The sample size was based upon sample sizes from similar previous studiesCitation15,Citation16. Formal sample size calculation can be difficult in valuation studies because the study is not designed to test a specific hypothesis. Instead the sample size can be determined in part in relation to the predicted confidence intervals around the mean utilities; the incremental gain in confidence intervals in moving beyond 100 cases becomes very small when the data are used to simply estimate mean scores. Participants were recruited via the interviewers using convenience sampling, and respondents were asked to provide written informed consent prior to data collection taking place. Participants were asked to complete a socio-demographic form, followed by the EQ-5D, to assess their own current health.

The main study consisted of two parts; the visual analogue scale (VAS) and the TTO exercise. The VAS allowed participants to familiarize themselves with the health states and to collect information on how the states were valued. This exercise involved participants ranking the health states on a 0–100 point scale, where 0 represented dead and 100 was full health. The states were presented to participants in a random order. The TTO exercise followed completion of the VAS. The aim of the TTO exercise was to elicit utility values for each of the nine included health states. Participants were presented with a series of choices where they were asked to choose between living in the health state for 10 years or living in a state of full health for 10-x years. Time in full health was varied until the participant was indifferent between the two choices. The amount of time in the state that the participant was willing to trade indicated the value or utility of the state. This utility value was recorded by the interviewer.

Results

The sample recruited broadly matched the demographics of the UK general public as described in the 2001 census dataCitation14 (). Participants own health was recorded via the EQ-5D (). This was compared with national results from a large UK studyCitation17. The study sample was found to have fewer moderate and extreme problems than the results found in Kind et al.Citation17, with no one in the study sample reporting any extreme problems. Therefore, the study sample reported a slightly better self-reported HRQoL compared to the UK general public.

Table 1. Study sample demographics compared to the 2001 census.

Table 2. Study sample EQ-5D results compared with a national surveyCitation17.

VAS values

reports the mean scores elicited from the VAS rating exercise. The highest mean value is for complete response (82.9), with the lowest value for progressed disease with large growth (44.5). The results show a logical decline in value as the states describe a greater burden to HRQoL.

Table 3. Mean VAS rating scores for aBCC states.

Utility values

reports the estimated utility values elicited for the nine included aBCC health states. The highest mean utility value was for the complete response state (0.94), whilst the state with the lowest value was progressed disease with large growth (6 cm) state (0.67). Each health state with a large lesion (6 cm) was valued lower than the equivalent state with a small lesion (2 cm). Stable disease with multiple small lesions was valued as less preferable than stable disease with a single small lesion, but not as low as stable disease with a large lesion. The post-surgical state was valued almost as low as the progressed disease with large growth (6 cm) states (0.72) and lower than all of the response stages of disease.

Table 4. Mean TTO health utilities for aBCC states.

Discussion

This study is the first to present societal utility values for health state vignettes associated with aBCC. For a number of patients, aBCC can be life threatening, but, even where this is not the case, the disease appears to have an impact on HRQoL. The physical nature of the lesions and the high levels of anxiety and depression reported by clinicians were found to be important aspects of the disease to include in the health states.

A number of interesting findings arose from this study. Complete response was valued most highly amongst the states. In reality, complete response is often associated with residual scarring (from treatment). Although participants felt this would have some impact on quality-of-life, the fact that the other areas described by the health state (including pain and activities) were not affected resulted in only a small decrease in overall utility. In contrast, progressed disease had the greatest burden on QoL. The size and number of lesions were also found to be important influences on QoL and therefore utility; treatment response with a larger lesion (6 cm) had a lower associated utility compared with the equivalent state with a smaller (2 cm) lesion; multiple small lesions were seen as less preferable than a single small lesion, but not as burdensome as a single large lesion.

The value for the post-surgical state was relatively low compared to full health. It was valued as having a greater impact on HRQoL than progressed disease with a small lesion. This suggests that members of the public perceived the impact of the disfigurement from extensive surgery for aBCC as commensurate with experiencing the actual disease. Further, where disfigurement occurs as a result of surgical intervention, the possibility of reconstructive surgery exists, although this may not be appropriate for all patients. Therefore, treatments that may prevent the need for surgery would be beneficial for patients.

Existing utility values are available for comparison to those elicited in this study. Examples of these can be found in a study which collected and documented utility values in a wide range of skin diseases (also using the TTO method)Citation18. The values listed include those for non-melanoma skin cancer (not including BCC) (0.976, SD = 0.054); lymphoma (mycosis fungoides) (0.867, SD = 0.298); and ulcers (0.923, SD = 0.154), and are reasonably comparable to those collected in this study. Unfortunately, Chen et al.Citation18 do not specify what stage of disease these values refer to; however, the values were elicited from patients prior to a definitive diagnosis, suggesting that they are likely to be at an earlier stage of disease. It must be noted though that, although they are collected directly from patients, the numbers in each of these categories in the Chen et al.Citation18 study are small, and the contents of the health states are not available for comparison. It should also be noted that aBCC is a severe form of a dermatological cancer, and it can be life limiting. Therefore, one may be more comfortable comparing the utility values to states related to those of oncological conditions, rather than purely dermatological. Three examples here that have used the TTO method to elicit utilities are: Stable metastatic renal carcinoma (0.795)Citation19; Stable soft tissue sarcoma (0.736)Citation20; Stable metastatic breast cancer (0.715)Citation21. Again, these values are comparable to the utilities collected for the stable states in this current study.

This study does have some limitations which should be taken into consideration when reviewing the results. The use of health state vignettes in valuation exercises to capture utilities has been criticized, partly because it is difficult to confirm the content validity of the vignettes themselvesCitation9. Where EQ-5D utility data are not available, NICECitation9 recommend the societal valuation of health state descriptions using the TTO methodology above other methods of valuation. The utility values elicited rely heavily upon the accuracy and validity of the descriptions developed and used. For a disease such as aBCC, it is challenging to develop accurate states given the rarity of the disease. There is also a vast difference in the way aBCC can present in terms of location and how the disease progresses. The available information was used to produce vignette descriptions as accurately and as detailed as possible. The content of the vignettes used in this study were based on published literature and clinician interviews. The EQ-5D was used as a framework in order to include some description regarding the main areas of quality-of-life—such as mobility, usual activities, etc. It is important to note, however, that, unfortunately, no patient interviews were conducted, due to the difficulty of accessing the aBCC population. Cognitive de-briefing interviews were conducted with members of the public to examine the acceptability of the vignettes. They were found to be clearly understood and participants reported that they could imagine themselves in the states sufficiently. Ethnic minorities were slightly under-represented compared with census data of the UK general public. The probable reason for this is that this study uses convenience sampling methods. Although utility values were elicited for nine health states related to aBCC, it was not possible to include all possible presentations of the disease. The study is constrained in terms of the number of states that it is possible to present to each individual, and increasing the number of health states can lead to respondent fatigue. Some potentially important health states were not included; for example the study does not include any description of adverse events which may have altered some of the treatment response states. Values for common toxicities could be identified from existing literature and methods exist for estimating a joint state utility. The utility values could also be age-adjusted using a similar method.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, the values elicited from such vignette studies can be important for decision-makers when evaluating cost effectiveness of treatments. Although the choice and categorization of states is inevitably a simplification, the logical pattern of results suggests that these data could be informative for decision analysis in this area.

Findings suggest that aBCC can be associated with a significant burden for individuals, even when their disease is stable. The psychological impact and cosmetic appearance of the lesions does appear to negatively affect HRQoL. The experience of progressed disease is seen as particularly debilitating as well as the associated extensive surgery that may be required to treat the lesions. Therefore, any treatment which may help reduce the need for surgery or that may reduce lesion number and size could be seen as beneficial.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Oxford Outcomes were paid a fixed fee by Roche Products Ltd to conduct this study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

AJL and SLS have disclosed that they are employed by Oxford Outcomes, an ICON plc Company, which provided research consultancy services paid for by Roche products Ltd. JG and KS have disclosed that they are employed by Roche Products Pty Ltd and Roche Products Ltd, respectively. They reviewed all versions of this manuscript and made comments and suggestions where appropriate. JTL and SK have disclosed that they provided clinical input for this study and helped with manuscript development. They have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose. JME Peer Reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (52.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr R. Herd, Western Infirmary, Glasgow, Scotland, UK and Richard Eaton, Roche Products Ltd, who contributed to this study.

References

- Lomas A, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath-Hextall F. A systematic review of worldwide incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol 2012;166:1069-80

- Kassi M, Kasi P, Afghan AK, et al. The role of fine-needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. ISRN Dermatology 2012;March:1-2. doi:10.5402/2012/132196

- Rubin AI, Chen E, Ratnder D. Basal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2262-9

- Schwipper V. Invasive basal cell carcinoma of the head and neck (Basalioma Terebrans). Facial Plast Surg 2011;27:258-65

- Lear J. Oral hedgehog-pathway inhibitors for basal-cell carcinoma. N Eng J Med 2012;366:2225-6

- Madan V, Lear J, Szeimies RM. Non-melanoma skin cancer. Lancet 2010;375:673-85

- Von Hoff D, LoRusso PM, Rudin CM, et al. Inhibition of the hedgehog pathway in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1164-72

- Ting PT, Kasper R and Arlette AP. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: report of two cases and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg, 2005; 9:10-15.

- National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence (NICE). Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. London, UK: NICE, 2008. http://www.nice.org.uk/niceMedia/pdf/TAP_Methods.pdf. Accessed 12 November 2012

- Shah K, Lloyd AJ, Oppe M, et al. One-to-one versus group setting for conducting computer-assisted TTO studies: findings from pilot studies in England and the Netherlands. Eur J Health Econ forthcoming; accepted article

- Behmand R, Guyron B. Resection of bilateral orbital and cranial base basal cell carcinoma with preservation of vision. Ann Plast Surg 1996;36:637-40

- Lear W, Akeroyd JE, Mittmann N. Measurement of utility in nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Cutan Med Surg 2008;12:102-6

- Takemoto S, Fukamizu H, Yamanaka K, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma: improvement in the quality of life after extensive resection. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 2003;37:181-5

- Office for National Statistics. Office for National Statistics, 2001. Census 2001. http://www.ons.gov.uk/census/index.html. Accessed 12 November 2012

- Swinburn P, Lloyd A, Nathan P, et al. Elicitation of health state utilities in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:1091-6

- Lloyd A, Nafees B, Narewska J, et al. Health state utilities for metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2006;95:683-90

- Kind P, Dolan P, Gudex C, et al. Variations in population health status: results from a United Kingdom national questionnaire survey. BMJ 1998;316:736-41

- Chen S, Bayoumi A, Soon S, et al. A catalogue of dermatology utilities: a measure of the burden of skin diseases. Soc Invest Dermatol Symp Proc 2004;9:160-8

- Swinburn P, Lloyd A, Nathan P, et al. Elicitation of health state utilities in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:1091-6

- Shingler S, Swinburn P, Lloyd AJ, et al. Elicitation of health state utilities in soft tissue sarcoma. Quality Life Res 2012; DOI 10.1007/s11136-012-0301-9.

- Lloyd A, Nafees B, Narewska J, et al. Health state utilities for metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2006;95:683-90