Abstract

Objective:

To assess rates and predictors of antipsychotic non-adherence and hospitalizations among patients with schizophrenia in separate Medicaid and commercial populations.

Methods:

This retrospective analysis used the Thomson Reuters MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid and IMS LifeLink Health Plan claims databases. These analyses included patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (295.xx) who received a prescription for an antipsychotic between January 1, 2008, and June 30, 2009 (date of first claim in window defined as index). Patients were required to have one additional antipsychotic prescription in the 1 year following index. Rates of adherence and psychiatric and all-cause hospitalization were evaluated. Multivariate logistic regression models identified predictors of antipsychotic non-adherence and hospitalization. These analyses were not intended to compare outcomes between the Medicaid and commercial populations.

Results:

Patients, 20,710 Medicaid and 7528 commercial, met all inclusion criteria. Both populations were ∼47% male, with a younger mean ± SD age among the Medicaid population (42.6 ± 14.1 vs 47.9 ± 17.1 years). Mean ± SD MPR in follow-up was 0.77 ± 0.25 in the Medicaid population (37.5% non-adherent) and 0.73 ± 0.27 in the commercial group (44.6% non-adherent). Rates of all-cause and psychiatric hospitalizations were 28.6% and 27.2%, respectively, among Medicaid and 29.2% and 26.3% among commercial patients. Newly starting antipsychotics and being non-adherent to therapy at baseline were both found to significantly increase the likelihood of non-adherence 12-fold in the Medicaid population (both p < 0.001) and 8-fold in the commercial population (both p < 0.001). Medicaid patients with a baseline psychiatric hospitalization had a 3-fold increased likelihood of hospitalization (p < 0.001) and commercial patients had a 2-fold increase (p < 0.001).

Limitations:

These two populations were not compared statistically; no conclusions as to the cause of any observed differences in outcomes can be made.

Conclusions:

Previous non-adherence, newly starting antipsychotic therapy, and previous hospitalization were significant predictors of non-adherence and hospitalization in Medicaid and commercial populations.

Introduction

Schizophrenic disorders afflict ∼1% of the adult population in the USCitation1. Symptoms of schizophrenic disorders range from experiencing hallucinations and delusions to having difficulty expressing emotion, communicating, developing plans, and enjoying daily activitiesCitation1. Because schizophrenia is a chronic, incurable condition, patients are generally given long-term treatment with conventional antipsychotics (first-generation), such as haloperidol, chlorpromazine, perphenazine, and fluphenzine, or atypical antipsychotics (second-generation), such as clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone.

Non-adherence to pharmaceutical therapy is common when patients are required over the long-term to take medications that require continued use to improve daily functioningCitation2, and it has been found to be particularly prevalent among patients with schizophrenic disorders. One article reported that 44% of Medicaid patients with schizophrenia were non-adherent over a 1-year follow-up periodCitation3. Common reasons for patients with schizophrenia to be non-adherent with prescribed medications include forgetting to take the medications, feeling that they are unnecessary, and side-effectsCitation4,Citation5.

In a previous study of Florida Medicaid patients with schizophrenia, we found that predictors of non-adherence included younger age, newly starting antipsychotics, previous diagnoses of substance abuse, use of concomitant medications such as mood stabilizers and antidepressants, and type of antipsychoticCitation3. Previous studies in both Medicaid and commercial populations have further found that patients with schizophrenic disorders who are non-adherent to therapy are more likely to experience relapse of symptoms and repeated hospitalizations and that, with each relapse, the likelihood of returning to a baseline level of functioning declinesCitation2,Citation3,Citation6–15.

The aim of this study was to expand previous analyses of non-adherence and hospitalization by evaluating a commercially-insured population, while also updating and confirming previous analyses among Medicaid patients with schizophrenia using more recent data. To that end, we conducted parallel retrospective database analyses using two separate claims databases from a Medicaid population and a commercially-insured population. The objectives of these analyses were to: (1) assess rates of antipsychotic non-adherence and hospitalizations among patients with schizophrenia treated with injectable and/or oral antipsychotics; and (2) examine predictors of antipsychotic non-adherence. Any comparisons of results between the populations are intended to be descriptive in nature.

Methods

Data sources

Medicaid population

The Thomson Reuters MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database contains information on more than 16 million individuals pooled from multiple geographically dispersed states, including patients covered by Medicaid managed-care plans. Information is available for non-dually eligible patients regarding inpatient, outpatient, and prescription drug claims. Data files include an eligibility file, a medical claims detail file, and a pharmacy claims detail file.

The eligibility file contains data on patient-level demographics, monthly eligibility status, and monthly dual (Medicaid and Medicare) eligibility status. Data in the medical claims detail file include up to 15 diagnoses from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), procedure codes from the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS), service start and end dates, place of service (including inpatient, outpatient, and long-term care), provider type, and payments (total gross payments to all providers). The pharmacy claims detail file provides prescription dispensing dates, national drug codes, quantity of drug dispensed, days supplied, and payment information.

Commercial population

The IMS LifeLink Health Plan Claims Database contains medical and pharmacy claims for more than 70 million members from more than 100 commercial health plans across the US. A standard extract consists of three files: a claims detail file, a pharmacy file, and an enrollment file. The claims detail file contains information on inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy claims, including ICD-9-CM diagnoses (up to 4) and HCPCS procedure codes, service start and end dates, place of service, and physician specialty. The pharmacy file contains information on national drug codes and days supplied. The enrollment file contains details on patient eligibility, age, sex, and geographic region.

Patient selection and follow-up

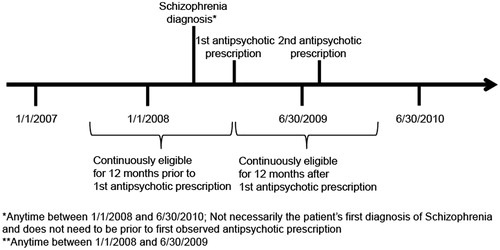

In each analysis (Medicaid and commercial), study patients were required to meet all of the following criteria (see for a sample patient timeline):

Presence of one inpatient or two outpatient healthcare claims with diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM 295.xx) between January 1, 2008 and June 30, 2010;

Receipt of a prescription for an antipsychotic between January 1, 2008 and June 30, 2009 (date of first antipsychotic in this period was defined as the index date, and patients were allowed to receive antipsychotics in the baseline period);

Receipt of at least one additional prescription for an antipsychotic within 1 year following the index date; and

Continuous eligibility in the plan in the 1-year pre-index and post-index periods (in the Medicaid population, it was required that patients were not dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare during this period); continuous eligibility was determined based on monthly eligibility indicators in the eligibility file for the Medicaid population and in the enrollment file for the commercial population.

Patients in both populations were followed for 1 year following the index date to evaluate outcomes.

Study measures

Pre-index (‘baseline’) demographic characteristics were evaluated, including age, sex, and race, as well as baseline clinical characteristics including use of concomitant medications (i.e., antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers, anticholinergic agents, and anticonvulsants), prevalence of concomitant diagnoses of substance abuse (ICD-9-CM codes 303.xx, 304.x, 305.0x, 305.2x–305.8x, or V65.42), and other psychoses (ICD-9-CM codes 290.xx–299.xx, excluding 295.xx), prevalence of Charlson comorbidities and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score, and the proportion of new starts on antipsychotic therapy. ‘New starts’ were defined as patients who received their first antipsychotic prescription in the 90 days prior to index (or at index).

Antipsychotic type(s) received in the year following index were grouped into five mutually exclusive categories. Antipsychotic groups were assigned in a hierarchy starting with patients receiving any injectable atypical (i.e., second-generation) antipsychotic, regardless of other antipsychotics received, followed by those receiving an injectable conventional (i.e., first-generation) antipsychotic, those receiving both an oral atypical and an oral conventional antipsychotic and no injectables, those receiving oral atypical antipsychotics only, and, last, those receiving oral conventional antipsychotics only.

Measures of adherence to antipsychotics in the follow-up period included medication possession ratio (MPR), persistence, and maximum continuous gaps in treatment. MPR was also assessed during the baseline period, as well as the number of days on treatment in the baseline period. MPR was defined as the number of days (ambulatory days) an antipsychotic was available (based on the days supplied reported on the pharmacy claim) divided by the number of days (ambulatory days) remaining in the follow-up period after the first antipsychotic was dispensed. Non-adherence was defined as a MPR of <0.8Citation14. Persistence was defined as the number of days between the first and last day receiving an antipsychotic divided by the number of days remaining in the follow-up period after the first antipsychotic was dispensed. Maximum continuous gaps in treatment were calculated as the maximum consecutive ambulatory days when the patient did not receive any antipsychotic between their first and last day receiving any antipsychotic.

Concomitant diagnoses of substance abuse and other psychoses were also evaluated in the follow-up period. The percentage of patients with psychiatric-related hospitalizations in the baseline period and psychiatric-related and all-cause hospitalizations in the follow-up period were evaluated. Psychiatric-related hospitalizations were identified as any hospitalization with a primary or secondary diagnosis of ‘mental disorders’ listed during the stay (ICD-9-CM codes 290.xx–319.xx). The number of psychiatric-related and all-cause hospitalizations and number of hospital days were also assessed. Finally, costs associated with hospitalizations were evaluated.

Data analyses

Separate analyses were conducted for each population, with no statistical testing of differences between populations intended. Each study population was described in terms of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics as well as measures of medication adherence and follow-up resource use and costs. All categorical variables were summarized descriptively using percentages and all continuous variables were summarized using mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range values. All cost measures were adjusted to 2010 US dollars using the medical care component of the consumer price index.

Multivariate logistic regressions were conducted to assess predictors of non-adherence in follow-up (MPR < 0.80), psychiatric-related hospitalization, and all-cause hospitalization. Baseline covariates included in the model to predict antipsychotic non-adherence included age, concomitant diagnoses and medication use, psychiatric hospitalization, baseline antipsychotic non-adherence, and whether the patient was newly starting antipsychotics. The regression equations predicting psychiatric-related and all-cause hospitalization included all of the predictors listed above for non-adherence, with the exception of non-adherence in the post-index period, which was used in place of baseline non-adherence. Predictors were considered significant if p < 0.05. No adjustment was made for multiplicity.

Results

Patient selection and baseline characteristics

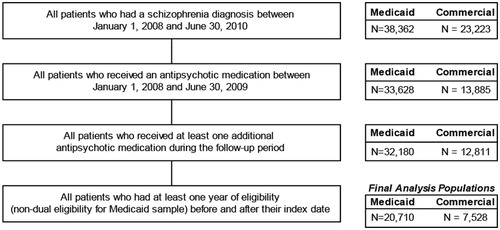

Among 38,362 Medicaid patients and 23,223 commercial patients with a schizophrenia diagnosis between January 1, 2008 and June 30, 2010, there were 20,710 Medicaid patients and 7528 commercial patients that met all other inclusion criteria (see ). Approximately 47% of patients in both populations were male. Average (±SD) age in the Medicaid population was 42.6 (±14.1) years, and 47.9 (±17.1) years in the commercial population (). Among Medicaid patients, more than half used antidepressants in the baseline period, and use of anticonvulsants was also common (over 44%). Thirty-six per cent of Medicaid patients had evidence of anxiolytic or anticholinergic use. Over 50% of commercial patients used antidepressants in the baseline period, with over one third using anticonvulsants and/or anxiolytics. Among patients in the Medicaid population, 15.7% had a concomitant diagnosis of substance abuse and 46.9% had a diagnosis of another psychosis (other than schizophrenia) in the baseline period. In the commercial population, 10.0% of patients had a substance abuse diagnosis and 54.0% had a diagnosis for another psychosis. The mean (±SD) Charlson Comorbidity Index score was 0.8 (±1.4) among Medicaid patients and 0.7 (±1.3) among commercial patients.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics, antipsychotic adherence, and hospitalizations among patients with schizophrenia.

Baseline antipsychotic non-adherence and psychiatric-related hospitalization

The majority of Medicaid patients with a diagnosis for schizophrenia had some baseline use of antipsychotics (87.4%), with an average (±SD) of 267 ± 97 days (∼9 months) of treatment in the baseline period (). Three-quarters of commercial patients with a diagnosis for schizophrenia had antipsychotic Mean (±SD). Baseline MPR was ∼0.8 ± 0.24 in both populations, with 34% and 38% of the Medicaid and commercial populations, respectively, being classified as non-adherent (i.e., MPR < 0.8) to antipsychotics in the baseline period. Baseline psychiatric-related hospitalizations occurred in 27.7% of Medicaid patients and 29.0% of commercial patients.

Follow-up antipsychotic adherence and concomitant medications

Almost 60% of Medicaid patients were on an oral atypical antipsychotic only, followed by 16.1% on an injectable conventional antipsychotic, 11.0% on both an oral conventional and oral atypical antipsychotics, 8.7% on an injectable atypical antipsychotic, and 4.2% on an oral conventional antipsychotic only (). Among commercial patients, oral antipsychotics were the most common treatment, with 70.7% of patients falling into the oral atypical antipsychotics only group, 12.3% into the oral conventional and oral atypical group, and 9.8% into the oral conventional only group. The remaining patients were receiving an injectable conventional antipsychotic (3.8%) or injectable atypical antipsychotic (3.3%).

Table 2. Antipsychotic adherence and concomitant psychiatric medications in the 12 months following index among patients with schizophrenia.

Mean (±SD) MPR in the 12 months after index was 0.77 ± 0.25 among Medicaid patients and 0.73 ± 0.27 among commercial patients. During the follow-up period, 37.5% of Medicaid patients and 44.6% of commercial patients were non-adherent. Antidepressants were the most commonly prescribed class of concomitant medications during follow-up, with 59.6% of Medicaid patients and 60.0% of commercial patients with use.

Follow-up healthcare resource use and costs

Rates of all-cause and psychiatric-related hospitalizations were 28.6% and 27.2%, respectively, in the Medicaid population and 29.2% and 26.3%, respectively, in the commercial population, indicating that the majority of hospitalizations among these patients in both populations were psychiatric-related. The mean (±SD) cost per all-cause hospitalization was $14,528 (±$21,113) among Medicaid patients and $9796 (±$11,462) among commercial patients. As the majority of hospitalizations were psychiatric-related, the mean cost per psychiatric-related hospitalization was similar to the mean cost for all-cause hospitalizations ($13,965 ± $19,285 for Medicaid patients and $10,111 ± $12,693 for commercial patients).

Predictors of antipsychotic non-adherence

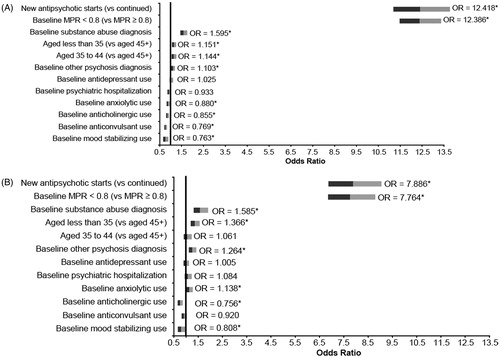

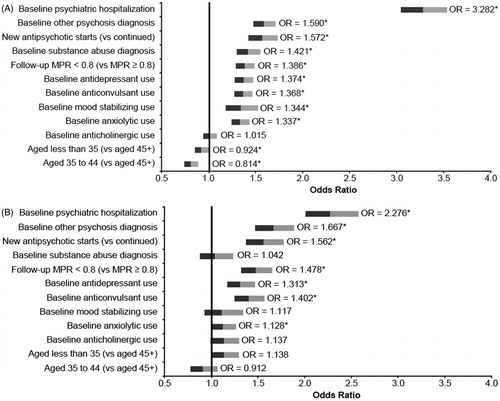

In the logistic regressions predicting non-adherence during the follow-up period (i.e., MPR < 0.80), younger age (Medicaid, p < 0.001 for age less than 35 and p = 0.004 for ages 35–44; commercial, p < 0.001 for age less than 35), baseline diagnoses of substance abuse and other psychoses (Medicaid, p < 0.001 for substance abuse and p = 0.015 for other psychoses; commercial, p < 0.001 for both substance abuse and other psychoses), baseline antipsychotic non-adherence (Medicaid, p < 0.001; commercial, p < 0.001), and newly starting antipsychotic therapy (Medicaid, p < 0.001; commercial, p < 0.001) were found to be significantly associated with a higher likelihood of non-adherence to antipsychotics among both Medicaid and commercial patients. Newly-starting antipsychotics and baseline antipsychotic non-adherence were both associated with a 12-fold increase in the likelihood of antipsychotic non-adherence in the follow-up period among Medicaid (OR = 12.42, 95% CI = 11.19–13.78, p < 0.001, newly starting; OR = 12.39, 95% CI = 11.48–13.37, p < 0.001, baseline non-adherence) patients and an 8-fold increase among commercial patients (OR = 7.89, 95% CI = 6.87–9.06, p < 0.001, newly starting; OR = 7.76, 95% CI = 6.85–8.80, p < 0.001, baseline non-adherence). See for Odds Ratios for each predictor in the logistic regression analysis predicting non-adherence in the follow-up period.

Figure 3. Predictors of future antipsychotic non-adherence among patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics (adjusted odds ratios) (A) Medicaid population, (B) Commercial population. Note: * indicates significance at P < 0.05.

Baseline use of concomitant psychiatric medications, including mood stabilizers (p < 0.001), anticonvulsants (p < 0.001), anticholinergics (p < 0.001), and anxiolytics (p = 0.001), were found to be associated with a significantly lower likelihood of antipsychotic non-adherence among Medicaid patients. Among commercial patients, baseline use of mood stabilizers and anticholinergics was found to be significantly associated with a lower likelihood of antipsychotic non-adherence (p = 0.032 and p < 0.001, respectively). Anxiolytic use was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of antipsychotic non-adherence (p = 0.032), and anticonvulsants were found to have no significant impact on antipsychotic non-adherence (p = 0.158).

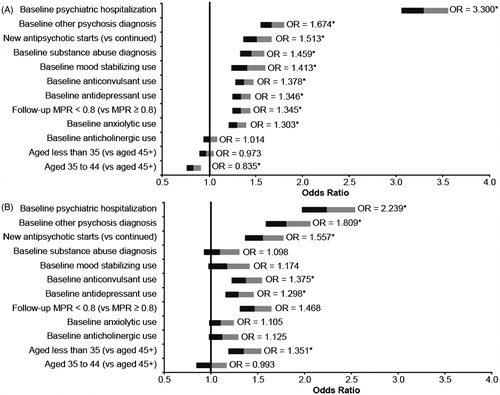

Predictors of hospitalization

Among Medicaid patients, younger age was found to be associated with a significantly lower likelihood of psychiatric-related or all-cause hospitalization (psychiatric-related, p < 0.001 for ages 35–44; all-cause p = 0.047 for age less than 35 and p < 0.001 for ages 35–44) ( and ). All other variables included in the model (baseline concomitant diagnoses and medication use, baseline psychiatric hospitalization, newly starting antipsychotic therapy, and antipsychotic non-adherence in the follow-up period, all p < 0.001) were associated with a significantly higher likelihood of an all-cause or psychiatric-related hospitalization in Medicaid patients, with the exception of baseline anticholinergic use, which was not significant (p = 0.710).

Figure 4. Predictors of psychiatric hospitalization among patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics (adjusted odds ratios) (A) Medicaid population, (B) Commercial population. Note: Follow-up MPR is for antipsychotics; * indicates significance at P < 0.05.

Figure 5. Predictors of all-cause hospitalization among patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics (adjusted odds ratios) (A) Medicaid population, (B) Commercial population. Note: Follow-up MPR is for antipsychotics; * indicates significance at P < 0.05.

In the commercial population, age less than 35 (vs 45+), baseline diagnosis of other psychosis, antidepressant use, anticonvulsant use, psychiatric hospitalization, newly starting antipsychotic therapy, and antipsychotic non-adherence in the follow-up period were found to be significantly associated with a higher likelihood of psychiatric-related hospitalization (all p < 0.001). These same parameters in addition to baseline anxiolytic use were significant predictors of all-cause hospitalization among commercial patients as well (all p < 0.001, except age less than 35 (p = 0.050) and anxiolytic use (p = 0.041) ( and ).

Discussion

Summary

We have conducted two parallel analyses of patients with schizophrenia on antipsychotic therapy, one in a Medicaid population and one in a commercially-insured population. Measures of baseline clinical characteristics, antipsychotic adherence, resource use, and costs were assessed and any comparisons between the two populations were descriptive in nature. Atypical and conventional injectable antipsychotics were commonly used in the Medicaid population, with approximately one-quarter of the population being prescribed an injectable medication. Rates of non-adherence were near 40% for both populations. All-cause and psychiatric-related hospitalization rates ranged from 26–29%.

In multivariate analyses, newly starting antipsychotics and baseline antipsychotic non-adherence were found to increase the likelihood of antipsychotic non-adherence during the follow-up period 12-fold in the Medicaid population and 8-fold in the commercial population. Medicaid patients with a baseline psychiatric-related hospitalization were 3-times more likely to have a psychiatric and all-cause hospitalization and commercial patients with a baseline psychiatric hospitalization were twice as likely. Newly starting antipsychotic, baseline concomitant diagnoses, antipsychotic non-adherence, and baseline concomitant use of psychiatric medications were also significant predictors of hospitalization.

Comparison to literature

Demographically, the populations were similar to those analyzed in other retrospective claims analyses of patients with schizophrenia on antipsychotic medications. In the Medicaid population the mean age was 43 years, with 47% of patients male, consistent with a previous Florida Medicaid analysisCitation3. Mean age in the commercial population was slightly older than that in a recently published study of commercial patients with schizophrenia (48 years vs 39–40 years); however, the proportion of males was similar (47% vs 50–51%)Citation15.

Overall, results regarding adherence to antipsychotics are comparable to those previously reported. In a previous analysis of Florida Medicaid claims from 2004–2005, MPR among patients with schizophrenia receiving oral and/or injectable antipsychotics was 0.79, which is close to the 0.77 reported in this study among Medicaid patients from several statesCitation3. A similar analysis of Arkansas Medicaid claims from 2000–2005 reported 0.73 MPR among schizophrenia patients receiving oral antipsychoticsCitation16.

Consistent with the prior Medicaid study, this study found that those newly starting antipsychotics were more likely to be non-adherent than continuing usersCitation3. This finding could potentially imply that it takes time for patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics to become stable and adherent to their treatment regimen. Baseline non-adherence was also found to be significant in predicting future non-adherence. However, while the multivariate analysis is intended to isolate the impact of each characteristic on future non-adherence, given that those newly starting antipsychotics may not have a baseline MPR to determine baseline non-adherence, it is difficult to separate the effects of each on predicting future non-adherence. This study did not include a detailed analysis comparing the characteristics of new starts to longer term users of antipsychotics; future studies exploring this relationship are necessary.

Findings were also consistent with previous work in noting that a baseline concomitant diagnosis of substance abuse and younger age were significantly associated with a higher likelihood of future antipsychotic non-adherenceCitation3. In contrast to the prior studyCitation3, this study found that baseline concomitant psychiatric medication use (i.e., antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers, anticholinergics, or anticonvulsants) was associated with a lower likelihood of future antipsychotic non-adherence. This association among commercial patients was varied with both positive (baseline anxiolytic use) and negative (baseline anticholinergic and baseline mood stabilizing use) predictors significantly impacting future antipsychotic non-adherence. This discrepancy may be due to differences in study design, including the fact that the current model included baseline antipsychotic non-adherence as a predictor (which was not included in the Florida study) and that the current analysis utilized more recent and geographically diverse multistate Medicaid and commercial data sets.

Law et al.Citation17 conducted an analysis of hospitalizations among patients with schizophrenia starting atypical antipsychotics in the Maine and New Hampshire Medicaid programs, and found that 46% of those patients had an all-cause hospitalization and 32% had a mental health-related hospitalization following the start of treatment. These rates are higher than the 29% and 27%, respectively, that we observed; however, Law et al. observed hospitalizations over a variable follow-up period of up to 3 years (2001–2003), whereas in our analysis the follow-up period was fixed at 12 months.

There is limited literature reporting rates of non-adherence and hospitalization among schizophrenia patients on antipsychotics in commercial populations, which is likely due to the fact that the majority of schizophrenia patients are covered under Medicare or Medicaid. An analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey found that 87% of respondents diagnosed with schizophrenia were reported to have Medicare or Medicaid coverage at any time during the year vs 15% with private insuranceCitation18. However, a recently published study compared commercially-insured patients with schizophrenia who were adherent to antipsychotics to those that were non-adherent, finding that non-adherence was associated with a higher likelihood of hospitalizationCitation15. Offord et al.Citation19 observed lower medication possession ratios in both adherent and non-adherent populations than were observed among the commercially-insured patients in the present study (a range of 0.22–0.73 vs 0.73); however, their study only included patients on oral antipsychotics, whereas the present study included a mix of patients on oral and long-acting injectable treatments, potentially allowing for better adherence. Furthermore, the definitions of ‘non-adherent’ were quite different between studies (discontinuation of treatment within 90 days of index vs MPR < 0.80 in our study). Previous studies of both commercial and Medicaid populations have presented similar findings, indicating that patients who are non-adherent to antipsychotics had a significantly higher likelihood of hospitalization than adherent patientsCitation3,Citation10,Citation14–16,Citation19.

Offord et al.’sCitation15 recent study of commercially-insured patients with schizophrenia on oral antipsychotics reported that all-cause annual total hospitalization costs ranged from $4211–$5850, with on average 0.38–0.57 hospitalizations per year. These results were similar to those in another published study of costs in this populationCitation2. When adjusted to a per hospitalization cost ($10,263–$11,082), these estimates are similar to those from the present study, which estimated costs per hospitalization among those with at least one hospitalization ($9746 among commercial patients).

Limitations

This study is subject to the limitations of retrospective claims-based analyses, such as coding errors and incomplete dataCitation20. Information was available only on the prescriptions that were filled, not on medications actually taken; therefore, our results for non-adherence may be under-estimated. This study was designed to evaluate the prevalent population of antipsychotic users with schizophrenia and, therefore, patients included in the study were observed at different time points in their continuum of care since diagnosis. New antipsychotic starts, or incident cases, were pooled with patients who may have been treated with antipsychotics for much longer. Differences in treatment patterns and medication adherence among these groups (e.g., injectable antipsychotics are not typically used among patients recently diagnosed and newly starting antipsychotic treatment; new starts may be less adherent to therapy) may have biased our results. As stated earlier, future studies comparing prevalent and incident populations are needed.

Finally, since the study was not designed to compare the Medicaid and commercial populations, no statistical testing of differences were conducted, and no multivariate analyses including payer type were conducted; therefore, no conclusions as to the cause of differences in outcomes across these two populations can be made.

Conclusions

Using more recent data, our results support the findings of previous studies that have examined the rates and predictors of non-adherence and hospitalization among populations of patients with schizophrenia. Our analysis of an under-studied commercial schizophrenia population found that these patients had lower rates of injectable antipsychotic use and somewhat higher rates of antipsychotic non-adherence—but similar rates of hospitalization—compared with those receiving Medicaid. After adjusting for baseline characteristics, predictors of antipsychotic non-adherence were generally similar in the Medicaid and commercial populations, including newly starting antipsychotics, previous antipsychotic non-adherence, younger age, and concomitant substance abuse and other psychoses diagnoses. Previous psychiatric-related hospitalization was the strongest predictor of all-cause and psychiatric-related hospitalization. These findings may assist health plan administrators, utilization management/quality improvement staff, and healthcare providers in identifying patients with schizophrenia at highest risk for antipsychotic non-adherence and hospitalization that might benefit from targeted interventions or case management in order to improve the quality of care for these patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

EM is an employee of the study sponsor, Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and is a Johnson & Johnson stockholder. KL, VF, JM, and JM have no disclosures to report.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank ApotheCom (funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC) for providing editorial and technical assistance for the paper.

References

- National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 2009. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/index.shtml. Accessed April 6, 2009

- Sun SX, Liu GG, Christensen DB, et al. Review and analysis of hospitalization costs associated with antipsychotic nonadherence in the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:2305-12

- Lang K, Meyers JL, Korn JR, et al. Medication adherence and hospitalization among patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv 2010;61:1239-47

- Liu-Seifert H, Adams DH, Kinon BJ. Discontinuation of treatment of schizophrenic patients is driven by poor symptom response: a pooled post-hoc analysis of four atypical antipsychotic drugs. BMC Medicine 2005;23:3-21

- Perkins D. Predictors of noncompliance in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;63:1121-8

- Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Larco J, et al. Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:692-9

- Ereshefsky L, Mannaert E. Pharmacokinetic profile and clinical efficacy of long-acting risperidone: potential benefits of combining an atypical antipsychotic and a new delivery system. Drugs R D 2005;6:129-37

- Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK. Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:805-11

- Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Blow FC, et al. Pharmacy data identify poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for admission. Med Care 2002;40:630-9

- Gianfrancesco F, Rajagopalan KS, Sajatovic M, et al. Treatment adherence among patients with schizophrenia treated with atypical and typical antipsychotics. Psychiatry Res 2006;144:177-89

- Becker MA, Young MS, Ochshom E, et al. The relationship of antipsychotic medication class and adherence with treatment outcomes and costs for Florida Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Adm Policy Mental Health 2007;34:307-14

- Valenstein M, Blow FC, Copeland LA, et al. Poor antipsychotic adherence among patients with schizophrenia: medication and patient factors. Schizophr Bull 2004;30:255-64

- Keith SJ, Pani L, Nick B, et al. Practical application of pharmacotherapy with long-acting risperidone for patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:997-1005

- Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:886-91

- Offord S, Lin J, Mirski D, et al. Impact of early nonadherence to oral antipsychotics on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with schizophrenia. Adv Ther 2013;30:286-97

- Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M, et al. Prospective validation of eight different adherence measures for use with administrative claims data among patients with schizophrenia. Value Health 2009;12:989-95

- Law MR, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, et al. A longitudinal study of medication nonadherence and hospitalization risk in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69:47-53

- Khaykin E, Eaton WW, Ford DE, et al. Health insurance coverage among persons with schizophrenia in the United States. Psychiatr Serv 2010;61:830-4

- Offord S, Wong B, Mirski D, et al. Healthcare resource usage of schizophrenia patients initiating long-acting injectable antipsychotics vs oral. J Med Econ 2013;16:231-9

- Schneeweiss S, Avorn J. A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;53:323-37