Abstract

Objective:

To identify relapse in schizophrenia and the main cost drivers of relapse using a cost-based algorithm.

Methods:

Multi-state Medicaid data (1997–2010) were used to identify adults with schizophrenia receiving atypical antipsychotics (AP). The first schizophrenia diagnosis following AP initiation was defined as the index date. Relapse episodes were identified based on (1) weeks during the ≥2 years post-index associated with high cost increase from baseline (12 months before the index date) and (2) high absolute weekly cost. A compound score was then calculated based on these two metrics, where the 54% of patients associated with higher cost increase from baseline and higher absolute weekly cost were considered relapsers. Resource use and costs of relapsers during baseline and relapse episodes were compared using incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and bootstrap methods.

Results:

In total, 9793 relapsers were identified with a mean of nine relapse episodes per patient. Duration of relapse episodes decreased over time (mean [median]; first episode: 34 [4] weeks; remaining episodes: 8 [1] weeks). Compared with baseline, resource utilization during relapse episodes was significantly greater in pharmacy, outpatient, and institutional visits (hospitalizations, emergency department visits), with IRRs ranging from 1.9–2.4 (all p < 0.0001). Correspondingly, relapse was associated with a mean (95% CI) incremental cost increase of $2459 ($2384–$2539) per week, with institutional visits representing 53% of the increase.

Limitations:

Relapsers and relapse episodes were identified using a cost-based algorithm, as opposed to a more clinical definition of relapse. In addition, their identification was based on the assumption from literature that ∼54% of schizophrenia patients will experience at least one relapse episode over a 2-year period.

Conclusions:

Significant cost increases were observed with relapse in schizophrenia, driven mainly by institutional visits.

Introduction

Schizophrenia, a chronic and debilitating mental illness that is characterized by a diminished capacity for learning, working, self-care, and interpersonal relationships, has a world lifetime prevalence of four in 1000 personsCitation1,Citation2. Although the incidence of schizophrenia is considered to be relatively low, the condition is a major contributor to the global burden of disease and is among the 20 leading causes of disability worldwideCitation3–5. The overall cost of schizophrenia in the US in 2002 was estimated to be $62.7 billionCitation6.

Most patients with schizophrenia experience a chronic course of the disease with many relapses, often characterized by exacerbation of psychoses and an increase in re-hospitalizationsCitation7,Citation8, which are associated with a significant cost burdenCitation9–11. Indeed, schizophrenia-related costs are ∼2–3-times higher for relapser patients compared with non-relapser patientsCitation10,Citation11. It has been reported that ∼54% of schizophrenia patients experience at least one relapse episode over a 2-year period following a response from the first episode of schizophreniaCitation12.

There is little consistency of measurement of schizophrenic relapse across studiesCitation13,Citation14. A narrow definition involves a clear re-emergence of psychotic symptoms, along with disturbances in functioning and social behavior as measured by clinical instruments such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, the Clinical Global Impressions Scale, and the Brief Psychiatric Rating ScaleCitation14–19. Alternatively, hospitalizations are often used as a broader measure of relapse for their comprehensive measurement and their relevance to health economicsCitation14,Citation18. The present study sought to develop a cost-based algorithm for use in empirically identifying episodes of relapse in newly-treated schizophrenia patients and to identify the main cost drivers of relapse in a real-world setting using a large health administrative claims database.

Methods

Data source

Health claims from Medicaid databases available from five states, Florida (1997Q3–2009Q2), Iowa (1998Q1–2010Q4), Kansas (2001Q1–2009Q2), Missouri (1997Q1–2010Q4), and New Jersey (1997Q1–2010Q4), were used. Medicaid database was chosen for this study based on the high prevalence of schizophrenia in this populationCitation20. Medicaid databases contain medical claims (e.g., type of service, service unit, date of service, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9], diagnoses, Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] codes, physician specialty, and type of provider), prescription drug claims (e.g., days of supply, units, dates of service, and National Drug Codes [NDCs]), and eligibility information (e.g., age, gender, enrollment start and end dates, and date/year of death, if applicable). The information was pooled from all five states.

Study design

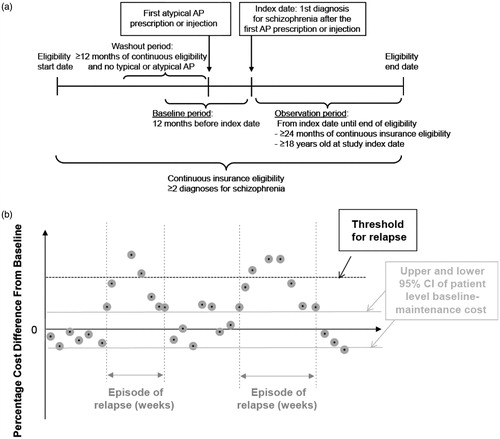

A retrospective, longitudinal cohort design was used to identify episodes of relapse based on cost in newly treated schizophrenia patients and to identify the main cost drivers of relapse (). Adult patients (≥18 years of age) included in this study had at least two diagnoses for schizophrenia (ICD-9: 295.xx) at any time during continuous insurance eligibility. The index date was defined as the date of the first diagnosis for schizophrenia after the first atypical antipsychotic (AP) prescription or injection following at least 12 months of continuous Medicaid enrollment without typical or atypical AP use (washout). Eligible patients also had at least 24 months of continuous Medicaid enrollment following the index date (observation period for identification of relapse episodes).

Algorithm for relapse identification

The cost-based algorithm developed to identify relapsers and relapse episodes used a public payer perspective to evaluate the potential drivers of these episodes of cost relapse without tying the start of the episode to a specific clinical event such as a hospitalization or emergency department visit. The algorithm was based on weeks associated with high cost increase from baseline and high absolute weekly cost, as follows.

Step 1: Identification of relapsers

Patients were ranked by their week with the highest percentage cost increase from baseline weekly maintenance cost during the first 24 months of the observation period. For each patient, the baseline weekly maintenance cost was defined as the mean weekly cost during the 12-month baseline period, excluding (1) the weeks before, during, and after initiation of AP, and (2) weeks with schizophrenia-related inpatient admission or emergency room visit.

To account for the regression to the mean phenomenon, patients were also ranked by their week with the highest absolute cost during the same period.

A compound score was then calculated using the sum of the squared ranks from the two classifications above (1 and 2). The top 46% of patients based on the compound score were considered non-relapsers, whereas the bottom 54% of patients, associated with higher cost increase from baseline and higher absolute weekly cost, were considered relapsers. The choice of this threshold was based on a study by Robinson et al.Citation12 indicating that ∼54% of schizophrenia patients will experience at least one relapse episode over a 2-year period.

Step 2: Identification of relapse episodes

The percentage cost increase from baseline and the highest absolute weekly cost of the patient (54th percentile) differentiating relapsers from non-relapsers served as the threshold for identifying relapse episodes for the relapsers ().

The weeks where the absolute weekly cost or the percentage cost difference was higher than the threshold for relapse acted as a flag to indicate a relapse episode. The beginning of an episode was defined as the first week with a statistically significant increase in weekly cost difference from the patient’s mean baseline maintenance weekly cost (±95% confidence interval [CI]). Similarly, the end of an episode was defined as the first week in which the percentage cost increase was no longer statistically significantly different from 0% (±95% CI). This method is similar to the SchulmanCitation21 method for identifying episodes of care.

Outcomes and statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of both relapsers and non-relapsers were evaluated during the baseline period. These characteristics included age, gender, race, state of residence, Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)Citation22,Citation23, healthcare costs, and length of observation period. Univariate descriptive statistics include mean (±standard deviation [SD]) and median values for continuous data and relative frequencies for categorical data. Statistical comparisons between groups were conducted using Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and two-sided Student’s t-tests for continuous variables.

Patterns of relapse episodes

Characteristics of identified relapse episodes were evaluated in relapsers during the observation period. Number and duration of relapse episodes per patient are reported. In addition, weekly cost during relapse episodes and total relapse episode costs are reported for each of the first five episodes separately. Numbers of weeks between consecutive relapse episodes and between index date and first episode are also reported. Descriptive statistics include mean (±SD) and median values, as well as the 25th and 75th percentiles.

Healthcare resource utilization

To assess the overall burden of relapse episodes in patients with schizophrenia, healthcare resource utilization of relapsers was compared between relapse episodes and the baseline period. All-cause and schizophrenia-related healthcare resource utilization, including pharmacy claims, institutional (i.e., inpatient admissions, emergency department visits, long-term care admissions, mental institute visits, outpatient mental institute visits, and inpatient admissions into a mental health facility) and outpatient visits, home visits, and other medical ancillary services were compared. Other medical ancillary services were defined as dental services, rehabilitation, substance abuse care, group/foster care, and in-community services, whereas outpatient visits were residually defined as services not categorized as institutional visits, home visits, or other medical ancillary services. Schizophrenia-related events were defined as services associated with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9: 295.xx). To compare the total number of claims during relapse episodes vs those during the baseline period, incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated, as were 95% CIs, using conditional Poisson regression models.

Healthcare costs

Weekly healthcare costs of relapsers at baseline and during relapse episodes, as well as cost differences between the two time periods, were evaluated. The total healthcare cost per-patient-per-week was stratified into pharmacy costs (including typical and atypical AP medication costs), all-cause and schizophrenia-related institutional visit costs (inpatient, emergency department, long-term care, and mental institute costs), outpatient costs, home costs, and other medical ancillary costs. All costs are expressed in US $2011. To address the non-normal distribution of costs, statistical differences and 95% CIs were estimated using non-parametric bootstrap procedures with 499 replicationsCitation24. The cost difference for each cost component was additionally expressed as a percentage of the total cost of relapse to identify the key cost drivers of relapse episodes.

No adjustment was made for multiplicity. Statistical significance was assessed with a two-sided test at an α-level of 0.05 or less. All analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 9793 and 8343 patients were identified as relapsers and non-relapsers, respectively. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups are presented in . Mean (median) age was 40.0 (39.0) years for relapsers and 40.8 (40.0) years for non-relapsers (p < 0.0001); 52.3% and 54.0% of relapsers and non-relapsers, respectively, were female (p = 0.0245). For relapsers, mean (median) baseline costs were $24,260 ($9984) for total pharmacy and medical costs, $3427 ($720) for schizophrenia-related services, and $425 ($148) for weekly maintenance costs. For non-relapsers, mean (median) costs were $22,280 ($11,401) for total pharmacy and medical costs, $3805 ($1119) for schizophrenia-related services, and $414 ($203) for weekly maintenance costs. Although total and schizophrenia-related pharmacy and medical costs were statistically significantly different between cohorts (p = 0.0005 and p = 0.0317, respectively), baseline weekly maintenance cost was not (p = 0.2963).

Table 1. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics.

Patterns of relapse episodes

Patterns of relapse episodes in the relapser population were assessed (). During the observation period, the mean (median) number of episodes was 9.0 (5), with a mean (median) duration of 10.6 (2) weeks. Duration of relapse episodes decreased over time, with a mean (median) duration of 34.2 (4) weeks for the first episode and 7.6 (1) weeks for remaining episodes. The mean (median) number of weeks between episodes was 12.5 (3). Similarly, the mean (median) total healthcare cost per episode decreased over time, with mean (median) costs of $35,323 ($7812) for the first episode and $11,293 ($4259) for remaining episodes. The differences between mean and median suggest a skewed distribution.

Table 2. Patterns of relapse episodes.

Healthcare resource utilization

Incremental resource utilization associated with relapse episodes was analyzed (). Relapse episodes were associated with significantly more medical claims across all categories, including more all-cause pharmacy claims (IRR [95% CI]: 2.02 [1.96, 2.07], p < 0.0001), all-cause institutional visits (IRR [95% CI]: 2.44 [2.33, 2.56], p < 0.0001), and all-cause outpatient visits (IRR [95% CI]: 1.86 [1.78, 1.95], p < 0.0001) than during the baseline period. More typical and atypical AP claims (IRR [95% CI]: 3.22 [3.10, 3.35], p < 0.0001), schizophrenia-related institutional visits (IRR [95% CI]: 6.68 [6.03, 7.40], p < 0.0001), and schizophrenia-related outpatient visits (IRR [95% CI]: 6.68 [5.98, 7.47], p < 0.0001) were reported during relapse episodes than during the baseline period.

Table 3. Resource utilization between baseline and relapse episodes.

Healthcare costs

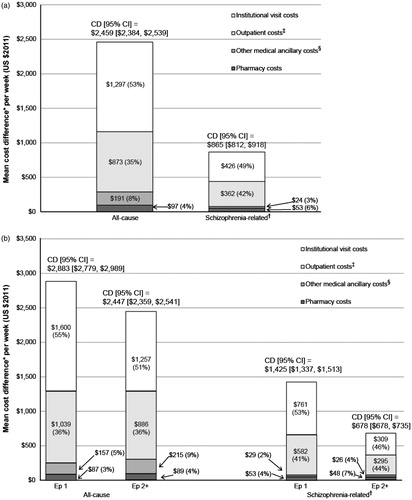

The different components of the total all-cause and schizophrenia-related cost difference between relapse episodes and the baseline period were assessed in the present study (). Furthermore, this information was stratified by first episode compared with all subsequent episodes (). In all relapse episodes, compared with baseline maintenance weekly costs, relapse episodes incurred greater all-cause weekly healthcare costs (mean incremental weekly cost [95% CI]: $2459 [$2384, $2539], p < 0.0001), representing a cost increase that is nearly 6-times larger than weekly baseline maintenance costs (mean [median]: $425 [$148]). As seen in , the first episode incurred a significantly greater incremental weekly cost difference ($2883 [$2779–$2989], p < 0.0001) compared with all subsequent episodes ($2447 [$2359–$2541], p < 0.0001).

Figure 2. (a) Mean cost difference and (b) Stratified mean cost difference per week between baseline and relapse episodes. CD, Cost difference; Ep, Episode. *Cost difference was calculated as the difference between relapse episodes and maintenance baseline mean weekly costs. Confidence intervals were calculated using bootstrap procedures and are not symmetric around the means. Percentages were calculated on the basis of non-rounded numbers. †Schizophrenia-related costs were defined as claims associated with a diagnosis for schizophrenia. Typical and atypical AP medications were used to define schizophrenia-related pharmacy costs. ‡Outpatient costs included costs associated with services not categorized as institutional visits, home visits, or other medical ancillary services. §Other medical ancillary service costs included costs associated with dental services, rehabilitation, substance abuse care, group/foster care, and in-community services.

In all relapse episodes, cost increases associated with institutional visits including hospitalizations ($1297 [$1250–$1342]) characterized most of the incremental cost associated with relapse episodes, with hospitalizations (excluding mental institute inpatient admissions) representing 36% ($883 [$844–$923]/$2459 [$2384–$2539]) and overall institutional visits representing 53% ($1297 [$1250–$1342]/$2459 [$2384–$2539]) of the cost increase. In addition to hospitalizations, institutional visit cost increase was composed of long-term care costs ($233 [$212–$252]), mental institute costs ($161 [$142–$182]), and emergency department costs ($21 [$17–$25]). Outpatient costs accounted for 35% ($873 [$810–$941]/$2459 [$2384–$2539]) of the overall cost increase. Similar cost component percentages were observed in the first episode compared with all subsequent episodes, with the mean schizophrenia-related incremental weekly cost increase associated with institutional visits more than twice as high for first episodes compared with all subsequent episodes ($761 vs $309).

Discussion

In this large retrospective cohort study using a health insurance claims database, relapse episodes were associated with greater healthcare resource utilization, including significantly more all-cause and schizophrenia-related pharmacy claims, institutional visits (including hospitalizations), and outpatient visits. Correspondingly, hospitalizations (excluding mental institute inpatient admissions) accounted for 36% and overall institutional visits represented 53% of the mean weekly cost increase from baseline during relapse episodes.

The algorithm developed in the present study to identify relapse episodes was inspired by the Schulman et al.Citation21 method to define episodes of care using claims data. These authors identified episodes of care for migraines in Medicaid data on the basis of daily charges after an index migraine, as compared with the period before. In the current study, the method was expanded to take into consideration weeks with high absolute cost, to account for the regression to the mean phenomenon and to identify expensive weeks that are of interest from a payer perspective.

Applying this algorithm in the context of identification of relapse in schizophrenia is unique in this study because it does not impose the occurrence of a specific event (e.g., hospitalization, change in medication) to identify episodes of relapse. Thus, this algorithm allowed the inclusion, in the episode, of costs before a specific event (e.g., hospitalization), as well as costs between the end of the event and return to maintenance costs. Furthermore, this algorithm allowed repeated outpatient or emergency department visits and significant changes to a patient’s medication regimen to also constitute a relapse episode. However, this approach solely based on costs did not capture relapse episodes for patients presenting with symptoms that did not require greater demand on healthcare services.

The finding that institutional visits accounted for most of the costs associated with relapse is not unique to this analysis and supports past workCitation9,Citation25. It is well accepted that specialist psychiatric hospital admissions or targeted treatments are sometimes needed during periods of relapse, and this places a significant demand on the healthcare systemCitation26. Others have reported that cost differences associated with relapse were driven not only by the volume of hospitalizations but also by an increase in length of hospital stay per admissionCitation11. Indeed, a recent European prospective study estimated that 61% of the cost difference between patients who relapse and those who do not was accounted for by hospital stayCitation10. This is consistent with the finding reported in the present retrospective study that 53% of the cost of relapse was associated with institutional visits, although not all institutional visits were hospitalizations. The European prospective study also reports that day hospital/day care or outpatient visits accounted for more than a quarter of the total incremental costs attributable to relapse; these findings are also consistent with the current studyCitation10. Similarly, a study by Ascher-Svanum et al.Citation11 using prospective observational data from the US found that higher costs in relapsers were associated not only with psychiatric hospitalizations and emergency department services, but also with medication management, day treatment, individual therapy, and Assertive Community Treatment (ACT)/case management.

In the current study, the observation period, beginning from the date of the first schizophrenia diagnosis (index date) after atypical AP initiation, was chosen in an attempt to best identify newly-treated patients. The mean time between the atypical AP initiation and the index date was longer than 350 days in both groups and was significantly shorter in relapsers (357 days vs 477 days, respectively; p < 0.0001). Therefore, it could be argued that identified non-relapse patients had been treated longer and, thus, had a better understanding of control.

In the examination of costs during relapse episodes as compared with during baseline, an important increase in all-cause and in typical and atypical AP claims was observed. In addition, compared with non-relapsers at baseline, identified relapsers had significantly lower all-cause and atypical and typical AP pharmacy costs, which suggests that AP treatment was associated with a reduced risk of relapse. While these results may be limited to the Medicaid population studied in this analysis, they are also consistent with previous studies reporting that earlier AP treatment is associated with better outcomesCitation27 and lends evidence to the hypothesis that the cost of proper AP treatment may be offset by the savings associated with prevention of future relapseCitation10.

This study found that newly-treated schizophrenia patients had a mean of nine relapse episodes, with the mean duration of the first episode being longer than that of all further episodes. This may reflect the fact that physicians and patients alike may gain a better understanding of how to manage the disease after the first relapse in these newly treated patients. Alternatively, these results may indicate that there is a need for more efficient care during the first relapse episode; however, actions targeted at reducing the length (and cost) of first relapse episode have unclear consequences on future relapse episodes.

The difference between the mean and the median of weekly and total costs per episode in this study suggests a skewed distribution, which lends further support for the use of non-parametric bootstrap methods in this analysis. However, mean rather than median costs are primarily presented, as the mean truly captures the cost burden of treating all patients and is of greater interest from a public and healthcare policy perspectiveCitation28. Moreover, this skewness in cost distribution is common in health economics evaluationsCitation28.

Despite the thorough study protocol and design, this study had several limitations, including the usual caveats associated with retrospective claims data analyses. First, claims data may be subject to inaccuracies in billing information and missing data. For example, the low proportion of schizophrenia-related costs represented within all-cause costs may be explained by misclassification or by classification of costs under a broader category such as mental health. In addition, claims data do not include certain information such as reasons for treatment and patient- or physician-reported outcomes (e.g., global assessment of functioning [GAF] scale), which would likely be available from a clinical trial. Relapsers and relapse episodes were identified using a compound score that included percentage cost difference from baseline, as opposed to a more clinical definition of relapse, which may have been more sensitive to patients with low baseline costs. The identification of relapsers was also based on the assumption that 54% of patients relapse following a response from a first episode of schizophrenia; however, it may be possible that, in some cases, the first relapse episode identified by the algorithm is, in fact, part of the first schizophrenia episode. Furthermore, when resource utilization and costs were examined, inpatient admissions may have been under-estimated because inpatient admissions to a mental health institute were categorized in the mental institute category. This study required patients to have at least 3 years of continuous Medicaid eligibility, and this may have introduced some selection bias in the selection of patients with schizophrenia. In addition, the data covered five states that may not be generalizable to other populations. Nevertheless, health insurance claims data remain a valuable source of information because they constitute a fairly valid, large sample of real-world practice data and allow outcomes to be examined in a real-world setting; thus they are potentially more representative of the study population.

Conclusions

On the basis of health insurance claims, this large observational study found that newly treated schizophrenia patients had a mean of nine relapse episodes over a mean observation period of ∼5.5 years, with duration of relapse episodes decreasing over time. Mean (median) duration of relapse episodes was 34 (4) weeks for the first episode and 8 (1) weeks for remaining episodes. Cost of relapse episodes decreased over time, with mean (median) costs of $35,323 ($7812) for the first episode and $11,293 ($4259) for remaining episodes. Relapse in schizophrenia was associated with a cost increase nearly 6-times larger than weekly baseline maintenance costs (mean incremental weekly cost [95%CI]: $2459 [$2384, $2539]; mean [median] baseline maintenance cost: $425 [$148]). Institutional visits, including hospitalizations, characterized most of the incremental cost associated with relapse episodes, with hospitalizations (excluding mental institute inpatient admissions) representing 36% of the cost and overall institutional visits representing 53%.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Lafeuille, Gravel, Lefebvre, and Duh are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has received research grants from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. Fastenau, Muser, and Doshi are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. JME Peer Reviewers have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Emma Hitt from Hitt Medical Writing and Matt Grzywacz from ApotheCom LLC, for editorial services.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, 2nd edn. APA, 2004. http://psychiatryonline.org/content.aspx?bookid=28§ionid=1665359. Accessed September 10, 2012

- Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, et al. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLOS Med 2005;2:e141

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD, eds. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Boston, MA: Harvard School of Public Health, 1996

- McGrath J, Saha S, Welham J, et al. A systematic review of the incidence of schizophrenia: the distribution of rates and the influence of sex, urbanicity, migrant status and methodology. BMC Med 2004;2:13

- World Health Organization (WHO). The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2008

- Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:1122–9

- Andreasen NC. Symptoms, signs and diagnosis of schizophrenia. Lancet 1995;346:477–81

- De Sena EP, Santos-Jesus R, Miranda-Scippa A, et al. Relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a comparison between risperidone and haloperidol. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria 2005;25:220–3

- Weiden PJ, Olfson M. Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1995;21:419–29

- Hong J, Windmeijer F, Novick D, et al. The cost of relapse in patients with schizophrenia in the European SOHO (Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes) Study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2009;33:835–41

- Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries DE, et al. The cost of relapse and the predictors of relapse in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2010;10:2

- Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56:241–7

- Falloon I. Relapse: a reappraisal of assessment of outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1984;10:293–9

- Burns T, Fiander M, Audini B. A Delphi approach to characterising ‘relapse’ as used in UK clinical practice. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2000;46:220–30

- Keks N, Ingham M, Khan A, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone v. olanzapine tablets for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: randomized, controlled, open-label study. Br J Pharmacol 2007;191:131–9

- Morken G, Widen J, Grawe R. Non-adherence to antipsychotic medication, relapse and rehospitalisation in recent-onset schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:32

- Stargardt T, Weinbrenner S, Busse R, et al. Effectiveness and cost of atypical versus typical antipsychotic treatment for schizophrenia in routine Care. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2008;11:89–97

- Hui CLM. Relapse in schizophrenia. H K Med Diary 2011;16:8–9

- Masand P, O’Gorman C, Mandel FS. Clinical Global Impression of Improvement (CGI-I) as a valid proxy measure for remission in schizophrenia: analyses of Ziprasidone Clinical Study Data. Schizophr Res 2011;126:174–83

- Wu EQ, Shi L, Birnbaum H, et al. Annual prevalence of diagnosed schizophrenia in the USA: a claims data analysis approach. Psychol Med 2006;36:1535-40

- Schulman KA, Yabroff KR, Kong J, et al. A claims data approach to defining an episode of care. Health Serv Res 1999;34:603–21

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83

- Quan HV, Sundararajan P, Halfon A, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Medical Care 2005;43:1130–9

- Mooney CZ, Duval RD. Bootstrapping: a nonparametric approach to statistical inference. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1993

- Almond S, Knapp M, Francois C, et al. Relapse in schizophrenia: costs, clinical outcomes and quality of life. Br J Psychiatry 2004;184:346–51

- Beard SM, Maciver F, Clouth J, et al. A decision model to compare health care costs of olanzapine and risperidone treatment for schizophrenia in Germany. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:165–72

- Perkins D, Lieberman J, Gu H, et al; HGDH Research Group. Predictors of antipsychotic treatment response in patients with first-episode schizophrenia, schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2004;185:18–24

- Thompson SG, Barber JA. How should cost data in pragmatic randomised trials be analysed? BMJ 2000;320:1197–2000