Abstract

Background:

Telaprevir (TVR,T) and boceprevir (BOC,B) are direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) used for the treatment of chronic genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. This analysis evaluated the cost-effectiveness of TVR combined with pegylated interferon (Peg-IFN) alfa-2a plus ribavirin (RBV) compared with Peg-IFN alfa-2a and RBV (PR) alone or BOC plus Peg-IFN alfa-2b and RBV in treatment-experienced patients.

Methods:

A Markov cohort model of chronic genotype 1 HCV disease progression reflected the pathway of experienced patients retreated with DAA therapy. The population was stratified by previous response to treatment (i.e., previous relapsers, partial responders, and null responders). Sustained virologic response (SVR) rates were derived from a mixed-treatment comparison that included results from separate Phase III trials of TVR and BOC. Incremental cost per life year (LY) gained and quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY) gained were computed at lifetime, adopting the NHS perspective. Costs and health outcomes were discounted at 3.5%. Uncertainty was assessed using deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses. Sub-group analyses were carried out by interleukin (IL)-28B genotype.

Results:

Higher costs and improved outcomes were associated with T/PR relative to PR alone for all experienced patients (ICER of £6079). T/PR was cost-effective for each sub-group population with high SVR advantage in relapsers (ICER of £2658 vs £7593 and £20,875 for partial and null responders). T/PR remained cost-effective regardless of IL-28B sub-type. Compared to B/PR, T/PR prolonged QALYs by 0.57 and reduced lifetime costs by £13,960 for relapsers. For partial responders T/PR was less costly but less efficacious than B/PR, equating to an ICER of £128,117 per QALY gained.

Limitations:

No head-to-head trial provides direct evidence of better efficacy of T/PR vs B/PR.

Conclusion:

T/PR is cost-effective compared with PR alone in experienced patients regardless of treatment history and IL-28B genotype. Compared to B/PR, T/PR is always cost-saving but only more effective in relapsers.

Introduction

As a major cause of advanced liver diseases such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection represents a significant public health burdenCitation1. In the UK, ∼146,000 people are chronically infected with HCV, with genotype 1 being the most common in some regions, and also the most resistant to treatmentCitation1. Up to 50% of patients with chronic HCV (CHC) infection fail to respond to initial therapy with the treatment regimen that has traditionally been considered the standard of care for genotype 1 HCV: 48 weeks of treatment with pegylated interferon (Peg-IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) in combination (PR)Citation2–4.

Without successful viral eradication, patients remain at risk of progression to more advanced, and ultimately more costly and hard to treat, stages of liver disease. Therapeutic options for such treatment-experienced patients have, until recently, been limited, with the most common approach—instigation of a repeat course of PR—associated with only a low probability of success. The sustained virologic response (SVR) rate is lowest in genotype 1 treatment-experienced patients (∼5–30%), highlighting the low likelihood of clearing the virus with current therapeutic options despite a course of treatment often lasting 48–72 weeksCitation5. Prior null-responders (those with a <2 log10 reduction in HCV RNA at week 12 of previous therapy) have a particularly high unmet need, with only one in 20 likely to clear the virus following re-treatment with standard therapyCitation6.

The introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) into clinical practice, however, has changed the landscape of HCV management in treatment-experienced patients. Telaprevir (TVR) and boceprevir (BOC), used in combination with PR, are DAAs that were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and by the European Medicine Agency (EMA) in 2011 for the treatment of chronic genotype 1 HCV infection in adults who are either treatment-naïve or were previously treated with interferon-based therapy and who have compensated liver disease including cirrhosisCitation7–10. Both agents inhibit the non-structural (NS) 3/4A serine protease that is a pre-requisite for HCV replication.

The objective of the current analysis was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the TVR-based regimen compared with PR alone or BOC-based therapy in treatment-experienced patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. Cost-effectiveness was considered in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained from the perspective of the National Health Service (NHS) in England and Wales.

Methods

The Markov model

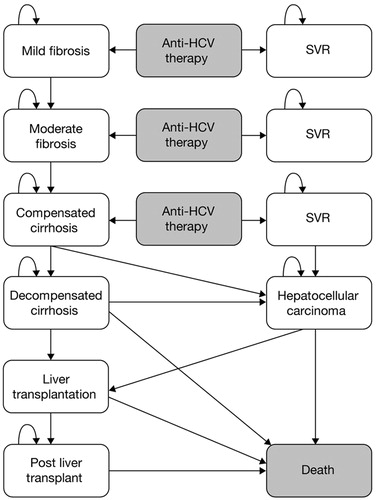

A Markov model was developed reflecting the natural history of CHC and simulating the pathway a patient may follow from the time they are re-treated onwards. A similar model had previously been developed for treatment-naïve patients, based on previous economic assessments and National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) appraisalsCitation11–14. The model structure is displayed in .

Figure 1. Markov model diagram. Background mortality is included in every state of the model. SVR, sustained virologic response; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Patients entered the model in the ‘mild fibrosis’ (defined as METAVIR F0-F1), ‘moderate fibrosis’ (defined as METAVIR F2), or ‘compensated cirrhosis’ (defined as METAVIR F3-F4) health states and received treatment with: TVR plus PR (T/PR), PR alone, or BOC plus PR (B/PR). Consistent with previous economic models, patients achieving an SVR following treatment were assumed to have cleared the virus, whereas unsuccessfully treated patients could either remain in their original health state for a period of time, or progress to the more advanced stages of liver disease such as decompensated cirrhosis or HCC. Patients with advanced liver disease (decompensated cirrhosis or HCC) were potential candidates for liver transplantation. Compared with treatment-naïve patients, treatment-experienced patients could progress more quickly from one health state to another as they were expected to have more severe disease due to the fact that more time for the disease to progress had passed after failure of initial treatment with PR alone. However, lack of data in the literature prevented the use of specific transition probabilities (TPs) for this patient population. For the early stages of disease we assumed that progression was faster as patients aged and used age-dependent TPs (), which were derived from an economic evaluation where TP inputs were stratified by age at treatment (<35, 36–45, and >45 years old)Citation15. The remaining TPs were taken from published articles and previous economic evaluationsCitation11–14,Citation16–18. It was assumed that, for cirrhotic patients, the risk of developing HCC was the same after reaching SVR due to the irreversible liver damage. All health states carried a risk of death (age-dependent general mortality and specific mortality associated with fibrosis/disease stage). Background mortality was taken from the UK Office for National Statistics and from previous economic evaluations. A cycle length of 1 year was used and a half-cycle correction was implemented. A lifetime time horizon was considered (i.e., up to 100 years of age) and the perspective was that of the NHS in England and Wales.

Table 1. Annual transition probabilities (TPs) used within the Markov model.

Model inputs

Patient characteristics and treatment regimens

The model followed cohorts of patients from the REALIZE and RESPOND-2 trials, two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase III studies recruiting patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection who had not shown a SVR to initial PR therapyCitation6,Citation19. REALIZE was designed to assess the safety and efficacy of T/PR vs PR alone in prior relapsers, partial responders, and null-respondersCitation6. RESPOND-2 compared the safety and efficacy of PR with that of two B/PR treatment regimensCitation19. Unlike the REALIZE trial, RESPOND-2 did not recruit any null responders. Even though a subsequent study (PROVIDE) investigated the efficacy and safety of BOC in prior null responders, at the time of analysis, no comparison between TVR and BOC was possible for this specific sub-group of patientsCitation20. Patients entering the model were stratified into three sub-groups depending on their treatment history:

‘Prior relapsers’ (53.5%): patients with undetectable HCV RNA at the end of prior therapy without subsequent attainment of a SVR.

‘Prior partial responders’ (19.1%): patients with a reduction in HCV RNA of at least 2 log10 at week 12 of prior therapy, but who never achieved undetectable HCV RNA levels while on treatment.

‘Prior null responders’ (27.4%): patients with a reduction in HCV RNA below 2 log10 at week 12 of prior therapy.

In each of these three sub-groups, patients could start treatment at three different stages of liver disease (mild fibrosis, moderate fibrosis, or cirrhosis), depending on their respective severity distribution (). The split between mild fibrosis (METAVIR F0-F1), moderate fibrosis (METAVIR F2), and cirrhosis (METAVIR F3-F4) used in the base case reflected the population of the REALIZE studyCitation6. Almost half of the patients were METAVIR F3-F4 vs one fifth in the RESPOND-2 studyCitation21.

Table 2. Model inputs.

The model compared three therapeutic strategies:

TVR regimen (T/PR):

Prior partial responders: TVR-based regimen in which patients received triple therapy with T/PR for 12 weeks followed by PR alone for another 36 weeks.

Prior relapsers and null responders: TVR response-guided therapy in which patients received triple therapy with T/PR for 12 weeks followed by PR for another 12 weeks (if HCV RNA undetectable at weeks 4 and 12 [i.e., extended rapid virologic response {eRVR} achieved]) or 36 weeks (if not achieving eRVR). This regimen is aligned with the approved regimen for TVR in prior relapsers in the UK.

PR alone regimen: PR dual therapy for 48 weeks.

BOC regimen (B/PR): BOC response-guided therapy in which patients received PR for 4 weeks followed by B/PR for another 44 weeks or 32 weeks if HCV RNA was undetectable at week 8–24.

Among prior relapsers subsequently treated with T/PR, 1.6% of patients failed to achieve an eRVR at week 4 and 12 and received 48 weeks of PRA total of 98.4% of patients receiving T/PR for 12 weeks followed by only 12 weeks of PR alone. For the prior null responders, 14.1% had to stop TVR at week 4 but still received 48 weeks of dual therapy with PR, thereby leaving 85.9% to receive the full 12 weeks of TVR and 48 weeks of PR. Finally for the T/PR regimen, all prior partial responders received the full treatment (i.e., 12 weeks of TVR and 48 weeks of PR). Patients receiving PR alone were assumed to receive the full treatment (30 weeks of PR treatment on average). Since no data were available by sub-group (i.e., prior partial responders and prior relapsers) for B/PR, data from the RESPOND-2 trial were used such that 46% of patients were assumed to be eligible for shorter treatment duration (32 weeks of B/PR and 36 weeks of PR)Citation19.

Resource use and healthcare costs

The frequency and intensity of tests and monitoring associated with each treatment regimen as well as unit costs were taken from a previous health technology assessment (HTA) reportCitation13. Any alteration to the initial protocol to include further monitoring (either due to the treatment itself or due to the presence of cirrhosis) was discussed with, and agreed to by, a clinical expert. The monitoring costs were computed for each treatment regimen (T/PR, B/PR, and PR alone) based on the treatment duration.

Each treatment group reported some adverse events, the most common being rash, pruritus, nausea, diarrhoea, and anaemiaCitation22. The costs of managing these adverse events were included in the analysis and taken from the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU)Citation23. Patients experiencing anaemia could use EPO in the BOC arm, in accordance with the trial protocol. The health state costs for SVR, mild and moderate fibrosis, compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, liver transplantation, and post-liver transplantation were taken from previous economic evaluations and updated to 2009/2010 values using the Hospital and Community Health Services (HCHS) pay and prices indexCitation13,Citation14,Citation23. Costs used in the model are displayed in .

Drug costs were taken from the British National Formulary (BNF) (2011)Citation24. Costs for Peg-IFN alfa-2a assumed a dosage of 180 μg/0.5 mL administered once per week, which corresponded to a weekly cost of £124.40. Since the RBV dose varied with patient weight, a daily dosage of 1000 mg was assumed, corresponding to a weekly cost of £77.08. TVR costs were estimated based on a 750 mg dose administered three times daily, corresponding to a weekly cost of £1866.50 or £22,398 for a full 12-week course of therapy. Costs of the PR and T/PR regimens were calculated based on the expected number of weeks that patients would receive double or triple therapies. The expected duration of therapy was contingent on virologic responses (e.g., eRVR positive/negative for relapsers among patients receiving T/PR), stopping rules, and premature discontinuations. BOC costs were inputted at £2800 for a 28-day, 336-tablet pack (excluding VAT)Citation24,Citation25. This equated to a cost of £30,800 for a 44-week course. However, the recommended duration of treatment with B/PR could be shorter (i.e., 24 weeks or 32 weeks) depending on patient and disease characteristics.

Health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL)

EQ-5D valuation index data captured from the REALIZE trial were applied to disutilities during the year of treatment. This enabled a differential impact on health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) to be appropriately implemented in the model, reflecting the type of treatment, the duration of therapy, and the occurrence of adverse eventsCitation13–16. Disutilities associated with the use of BOC were assumed to be the same as those associated with T/PR given the lack of data in the literature for BOC on this topic during this analysis. The remaining utilities associated with the other health states were the same as the ones used by Hartwell et al.Citation14. All utilities are presented in Citation14,Citation15. EQ-5D valuation index data captured from the trials were applied to utilities during the year of treatment. This enabled a differential impact on HRQoL to be appropriately implemented in the model, reflecting both the type of treatment and the duration of therapy that patients received.

Efficacy: SVR rates

The relative efficacy of T/PR compared with PR alone or B/PR was estimated by a meta-analysis ()Citation26. This analysis was run on three studies (REALIZE, RESPOND-2. and Flamm et al.) that included the three main treatments of interestCitation6,Citation21,Citation27. This analysis was carried out on the trial results and differs from the ones reported in the respective label for TVR (prior relapsers 84% for T/PR vs 22% for PR; prior partial responders 61% for T/PR vs 15% for PR; prior null responders 31% for T/PR vs 5% for PR) and BOC (prior relapsers 75% for B/PR vs 29% for PR; prior partial responders 52% for B/PR vs 7% for PR; prior null responders – no data at the time of this analysis)Citation9,Citation10.

Table 3. Sustained virological response (SVR) rates inputted into the modelCitation6,Citation21,Citation27.

The pooled SVR estimates associated with prior relapsers were 23.5%, 83.0%, and 60.7% for PR, T/PR, and B/PR, respectively; with prior partial responders, these estimates were 14.8%, 57.2%, and 59.5%, respectively; and with prior null-responders, estimates for PR and T/PR were 5.4% and 29.2%.

Cost-effectiveness analyses

The model estimated the total lifetime costs and QALYs per patient for the T/PR, PR alone, and B/PR regimens. Future costs and outcomes were discounted at the recommended rate of 3.5% per yearCitation28. The results of the analyses are presented as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) expressed as cost per QALY gained.

Sub-group analyses: IL-28B genotype

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the region of the IL-28B gene have been strongly associated with treatment success in HCV in genotype1-infected patients treated with PR alone; in such analyses, TT or CT IL-28B genotypes were associated with lower SVR rates compared with the CC genotypeCitation29–32. Post-hoc sub-group analyses were performed to assess the incremental efficacy of T/PR over PR alone in patients with different IL-28B genotypes using data from the REALIZECitation6,Citation21.

Sensitivity analyses

One-way sensitivity analyses were conducted on parameter values to examine their effects on ICERs, including discount rate (0% and 6% for both costs and benefits), SVR rates, TPs, utility values, treatment duration, and health state costs.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses (PSAs) were also carried out by varying key model parameters randomly across their potential distributions over 1000 iterations using values drawn at random from the probability distributions. Each resulting output was plotted as a point on the cost-effectiveness plane, yielding a scatter plot. From these outputs, cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were derived, which indicated the probability of each regimen being cost-effective, over a range of possible values of willingness-to-pay.

Results

Cost-effectiveness analyses: base case

In the base case, the T/PR regimen was projected to improve morbidity and mortality compared with PR alone, yielding a higher number of QALYs (). T/PR was cost-effective vs PR alone across the full cohort of treatment-experienced patients with an ICER of £6079. The sub-group of treatment-experienced patients benefiting the most from T/PR was the ‘prior relapsers cohort’. Incremental discounted life expectancy was 0.91 for all treatment-experienced patients and 1.13, 0.83, and 0.52 for prior relapsers, prior partial responders, and prior null responders, respectively. That the benefit of T/PR vs PR alone was greatest in the prior relapsers sub-group was also apparent from analysis of the number of discounted QALYs incurred. ICERs ranged from £2658 per QALY gained among prior relapsers to £20,875 among prior null responders. This result was expected considering the differences in SVR rate in the different patient sub-groups and given the fact that SVR is considered necessary to prevent patients progressing to more severe and costly health states. This also explains how the additional costs incurred by the introduction of TVR are estimated to be offset by the benefits that result from the prevention of complications associated with chronic genotype 1 HCV infection.

Table 4. Cost-effectiveness results: base case.

The T/PR regimen ‘dominated’ the B/PR regimen in the prior relapser sub-group as it was £13,960 less expensive and resulted in 0.57 more QALYs, as shown in .

T/PR was shown to be cost-saving (−£7687) compared to B/PR in prior partial responders but for a loss of −0.06 QALY. The ICER associated with B/PR vs T/PR in prior partial responders was more than £128,000. Regarding clinical outcomes, the base case analysis estimated that treating 1000 treatment-experienced patients with T/PR would avoid 250 cases of cirrhosis, 19 liver transplants, and nine deaths at lifetime compared to PR, and 85 cases of cirrhosis, six liver transplants, and three deaths compared to B/PR.

Sub-group analyses: IL-28B genotypes

In comparison with PR alone, T/PR remained a cost-effective treatment regardless of IL-28B genotype (CC: £9747/QALY; CT: £5986/QALY; TT: £6647/QALY). In patients with the CT or TT genotype, gains in QALY were greater, and incremental costs lower than in those with the CC genotype, resulting in lower ICERs.

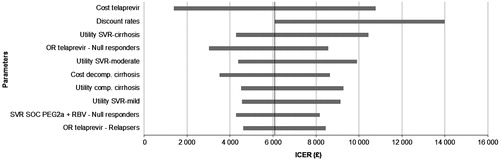

Sensitivity analyses: deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA) and PSA

The ICERs of T/PR vs PR alone were found to be sensitive to changes in key parameters that included discount rates, the cost of TVR, the utilities associated with reaching SVR, the utilities associated with entry health states, and the SVR associated with TVR (). For the comparison with B/PR, T/PR ‘dominated’ in prior relapsers (i.e., more efficacious and less costly than B/PR) but not in prior partial responders where T/PR was less costly and efficacious.

Figure 2. Tornado chart of cost per QALY gained for the T/PR regimen vs PR alone for all treatment-experienced patients. PR, peginterferon/ribavirin; T/PR, telaprevir plus PR; SVR, sustained virologic response; SOC, standard of care; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

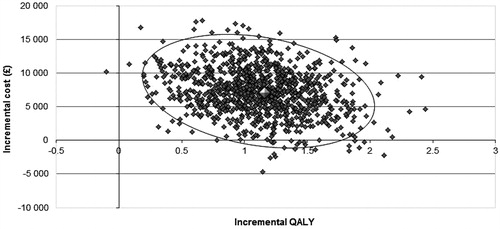

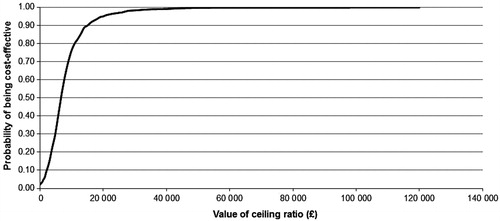

The PSA showed that, compared with PR alone, all the simulations fell in the north-east quadrant of the cost-effectiveness plane (), generating a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve which showed that at least 95% of the simulations resulted in an ICER per QALY gained below £20,000 in all the populations of interest and ∼98% fell below £30,000 (). This demonstrates the high likelihood of TVR being cost-effective compared with PR alone across all treatment-experienced populations.

Discussion

Treatment failure occurs in ∼70–95% of treatment experienced patients with chronic genotype 1 HCV infection who receive PR alone. These patients include prior relapsers (who experience reappearance of serum HCV RNA after achieving an undetectable level at the conclusion of a course of therapy), prior partial responders (whose HCV RNA levels drop by at least 2 log10 IU/mL at treatment week 12 but in whom HCV RNA is still detected at treatment week 24), and prior null responders (who fail to achieve a 2 log10 decline by week 12). The majority of the treatment-experienced patients are not offered re-treatment with the same regimen. Therefore, the PR alone strategy is hypothetical. Until recently, approaches to the re-treatment of previously treated patients were limited to strategies such as the use of higher doses of interferon, longer duration of therapy, and, on occasion, higher doses of ribavirin. Two protease inhibitors approved in 2011 have demonstrated that patients previously treated (including relapsers, partial, and null responders) have higher SVR rates than PR alone when retreated with TVR or BOC in combination with PR. Regimens incorporating DAAs also allow reductions in the duration of therapy, particularly in naive patients with eRVR. Taking such factors into account, NICE recommended TVR or BOC in combination with PR as treatment options for CHC in both treatment-naive and -experienced patientsCitation1. Considering the current strains on healthcare budgets, it is important to appraise the benefits and costs associated with new interventions by a cost-effectiveness analysis. In the case of chronic genotype 1 HCV infection, it is even more important to assess benefits over the long-term (i.e., 20 or 30 years) since the complications associated with infection progress slowly and have severe consequences over time. All these issues make the use of decision modelling necessary in order to appreciate the benefits of the TVR regimen and account for the costs offset on a long-time horizon.

In a previously submitted dossier in support of PR re-treatment in patients who did not respond or relapsed on previous treatment with peg interferon, treatment of genotype 1 prior non-responders given PR was associated with a cost of £29,224 and 11.69 QALYsCitation33. The results are quite similar with what we found in our study (£35,743 and 10.38 QALYs).

Based on our base case assumptions of clinical efficacy, TPs, and costs, we found that re-treating patients with chronic genotype 1 HCV infection with the triple combination of TVR and PR regimen resulted in an ICER of £6079 compared with re-treatment using PR alone. The TVR response-guided regimen demonstrated an increase in life expectancy of almost a year and a gain of 1.16 QALYs at lifetime over PR alone. While T/PR was cost-effective compared with PR alone across the treatment-experienced population, different ICERs were observed between patients according to their previous response to treatment. Thus, for prior null responders, the ICER reached £20,875, whereas treatment of prior partial responders and prior relapsers were associated with much lower ICERs of £7593 and £2658, respectively. These findings are explained by differences in SVR rates in patients with prior relapsers vs prior partial and null responders. T/PR remained a cost-effective treatment compared with PR alone, regardless of IL-28B genotype.

Re-treatment with TVR, therefore, is highly cost-effective, and these results justify the rationale for treating patients before they progress to severe disease stages, where associated morbidity and mortality and the cost of management is high. For prior relapser patients without cirrhosis, who achieve an eRVR, the shorter duration of therapy (total of 24 weeks) can potentially motivate patients to complete the full course of therapy, thereby maximizing the opportunity to clear the HCV virus. Prior null responders, with and without cirrhosis, remain hard-to-treat patients despite their greater clinical need. Response rates in this group remain sub-optimal with PR alone and adverse events are more frequent in patients with cirrhosis. Although the ICER in prior null responders is relatively high, TVR provides clinical benefits compared with PR alone (SVR rates of 31% vs 5% for TVR vs PR alone, respectively) and consequently more patients can achieve cure with TVRCitation6,Citation9. Patients with cirrhosis treated with TVR or BOC may require several secondary measures to manage complications for anaemia, neutropaenia, or thrombocytopaenia, or even blood transfusions, adding to the costs of treatment. The trial outcomes are likely to be best case scenarios. The safety profile of PI-containing regimens in patients with cirrhosis was found very challenging in real life and may impact the cost-effectiveness results compared to PR alone. This model didn’t include cost savings from the reduction of the incidence, prevalence, and transmission of HCV disease.

When compared with a BOC-containing regimen, the model showed that TVR regimen is cost-effective for prior relapsers and cost saving for prior partial responders (meaning it is less costly and less efficacious).

For improvement of 0.06 QALY, the ICER associated with B/PR compared to T/PR was more than £130,000 in prior partial responders. While treating prior null responders with advanced liver disease remains to be a challenge, cost-effectiveness of TVR relative to BOC could not be evaluated due to lack of clinical data for BOC in this population at the time of our analysis. At the time this analysis was conducted, REALIZE was the only published clinical trial involving a protease inhibitor in genotype 1 chronic HCV that provided efficacy and safety data for patients with a null response to prior therapyCitation6.

The robustness of the current results was demonstrated by sensitivity analyses and the consistency of the results of sub-group analyses. The DSAs showed that the model outputs were sensitive to the discount rates used on both costs and benefits. This is not unexpected given the lifetime perspective considered in this analysis. The model was also shown to be robust to changes in key parameters like SVR rates and transition probabilities. These results showed the high likelihood of TVR being cost-effective compared with PR alone. This was confirmed by the PSA and the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve, in which ∼95% of the simulations had an ICER per QALY gained below £20,000 and ∼98% below £30,000. These results could not be explained solely by the greater efficacy of TVR in treatment-experienced patients, but were also related to the fact that costs were largely offset by preventing patients from progressing to more debilitating and costly health states.

The extensive sensitivity analyses that were performed showed that the model provided robust evidence of the high likelihood of TVR being cost-effective not only for all treatment-experienced patients, but also for the sub-groups of interest (i.e., prior partial responders and prior relapsers). However, this model has a few limitations. There is a lack of data to allow us to have a good understanding of the evolution of patients who have previously failed treatment. Model parameters such as transition probabilities or utility values were not derived from the population of interest but were taken from a previous economic assessment developed for treatment-naïve patients. In contrast to the naïve population, treatment failure with PR is more common in patients with cirrhosis (and potentially with TVR and BOC). Thus, a treatment-experienced cohort would comprise more patients with higher rates of advanced staged of fibrosis, and would progress more quicklyCitation13,Citation14. Sensitivity analyses explored the impact of variation in TPs and T/PR remained a cost-effective treatment option in treatment-experienced patients. Once available, results from future observational studies designed to follow-up patients being re-treated would be better inputs to inform this model. In the absence of direct head-to-head studies between TVR and BOC, comparative data based on direct head-to-head evidence from a prospective, randomized, controlled, clinical trial could not be utilized. Instead the relative efficacy of TVR was derived from a mixed-treatment comparison in treatment-experienced patients. The BOC and TVR trials could only be linked in the network through the comparison of PRα-2a vs PRα-2b. As most comparisons are based on only one study, the estimate of the between-study variance had poor precision. As a result, it was hard to differentiate heterogeneity from differences caused by the different treatments compared. In the treatment-experienced patients, none of the interactions between treatment and baseline characteristics were found to be significant for both TVR and BOC. The meta-analysis showed that the results for this population are completely driven by the evidence for relapsers. For partial responders, there was high uncertainty on the comparative efficacy, reflected by the probability of one treatment being more efficacious than the other close to 50%, mainly due to the low sample size of this sub-group in the trials.

Factors such as alcohol abuse contribute significantly to HCV disease progression, but were not incorporated in this model. The development of viral drug resistance could limit future therapy options, and common resistance mutations to BOC and TVR have been described. However, the implications of resistance are not yet clear and, therefore, could not be incorporated in this modelCitation34,Citation35.

Conclusions

This cost-effectiveness model for treatment-experienced patients projected that first-generation protease inhibitors would be the preferred option compared with PR alone based on the current assumptions. Our results suggest that T/PR is cost-effective compared with PR alone in treatment-experienced patients with chronic genotype 1 HCV infection, regardless of previous treatment response (i.e., relapsers, partial or null responders) and IL-28B genotype. Our study also shows that the cost-effectiveness of T/PR compared to B/PR depends on the population being treated; T/PR is shown to be the dominant strategy in prior relapsers but less costly and efficacious in prior partial responders with the ICER associated with B/PR compared to T/PR being more than £128,000. These findings were robust and were maintained in the sensitivity analyses, in which a wide range of assumptions regarding efficacy, HRQoL, and costs were tested.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This analysis was funded by Janssen Pharmaceuticals. The authors confirm that the paper is an accurate representation of the study results. Several authors are employees of the sponsor and were involved in the study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Declaration of financial/other interests

S. Cure and FB are employees of OptumInsight, who received funding from Janssen Pharmaceuticals. SG, S Curtis, and SL are employees of Janssen Pharmaceuticals. JME Peer Reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose. GD has received consulting fees from Roche, Merck, and Janssen pharmaceuticals.

Acknowledgements

We thank Catherine Elliott (Gardiner-Caldwell Communications) for general editing/styling and co-ordination support, which was funded by Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Author contributions: S. Cure, F. Bianic, S. Gavart, and G. Dusheiko were involved in designing these analyses; S. Curtis, and S. Lee were involved in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; S. Cure and S. Lee wrote the first draft of the report, which was subsequently critically reviewed by all authors; all authors were involved in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- NICE publishes final draft guidance on telaprevir for chronic hepatitis C. London, UK: NICE, 2012. http://www.nice.org.uk/newsroom/pressreleases/FinalDraftTelaprevirHepC.jsp. Accessed 2012

- Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2002;347:975-82

- Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001; 358:958-65

- Ghany MG, Nelson DR, Strader DB, et al. An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2011;54:1433-44

- EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 2011;55:245-64

- Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, et al. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2417-28

- FDA. FDA approval of Incivek (telaprevir), a direct acting antiviral drug (DAA) to treat hepatitis C (HCV). USA: FDA, 2011. http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ByAudience/ForPatientAdvocates/ucm256328.htm. Accessed 2011

- FDA. FDA approval of Victrelis (boceprevir), a direct acting antiviral drug (DAA) to treat hepatitis C (HCV). USA: FDA, 2011. URL:http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ByAudience/ForPatientAdvocates/ucm255413.htm. Accessed 2011

- EMA. EMA approval for Incivo (telaprevir): EMEA/H/C/002313. EMA, 2011. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002313/human_med_001487.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. Accessed 2011

- EMA. EMA approval for Victrelis (boceprevir): EMEA/H/C/002332. EMA, 2011.

- Bennett WG, Inoue Y, Beck JR, et al. Estimates of the cost-effectiveness of a single course of interferon-alpha 2b in patients with histologically mild chronic hepatitis C. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:855-65

- Wright M, Grieve R, Roberts J, et al. Health benefits of antiviral therapy for mild chronic hepatitis C: randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2006;10:1-113, iii

- Shepherd J, Jones J, Hartwell D, et al. Interferon alpha (pegylated and non-pegylated) and ribavirin for the treatment of mild chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2007;11:1-205, iii

- Hartwell D, Jones J, Baxter L, et al. Peginterferon alfa and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C in patients eligible for shortened treatment, re-treatment or in HCV/HIV co-infection: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2011;15:i-210

- Grishchenko M, Grieve RD, Sweeting MJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pegylated interferon and ribavirin for patients with chronic hepatitis C treated in routine clinical practice. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2009;25:171-80

- Grieve R, Roberts J, Wright M, et al. Cost effectiveness of interferon alpha or peginterferon alpha with ribavirin for histologically mild chronic hepatitis C. Gut 2006;55:1332-8

- Fattovich G, Giustina G, Degos F, et al. Effectiveness of interferon alfa on incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and decompensation in cirrhosis type C. European Concerted Action on Viral Hepatitis (EUROHEP). J Hepatol 1997;27:201-5

- Siebert U, Sroczynski G, Rossol S, et al. Cost effectiveness of peginterferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin versus interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Gut 2003;52:425-32

- Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, et al. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1207-17

- Vierling J, Flamm S, Gordon S, et al. Efficacy of Boceprevir in prior null responders to peginterferon/ribarivin: the PROVIDE study. 62nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; San Francisco, CA. November 4--8, 2011

- Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, et al. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1207-17

- Clinical study report: ADVANCE. 2010.

- Curtis L. Unit costs of Health and Social Care. Canterbury: Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, 2010

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain 9 A.D.No.58, 2011

- Prescription drug database and drug prescribing guide. MIMS online. 2012

- Cure S, Diels J, Gavart S, et al. Efficacy of telaprevir and boceprevir in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C patients: an indirect comparison using Bayesian network meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin 2012;28:1841-56

- Flamm S, Lawitz E, Jacobson I, et al. High sustained virologic responses among genotype 1 previous non-responders and relapsers to peginterferon/ribavirin when re-treated with boceprevir plus peginterferon Alfa-2a/Ribavirin. European Association for the Study of the Liver, 2011

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisals. 2008. London, UK: NICE. http://www.nice.org.uk/media/B52/A7/TAMethodsGuideUpdatedJune2008.pdf. Accessed 2011

- Rauch A, Rohrbach J, Bochud PY. The recent breakthroughs in the understanding of host genomics in hepatitis C. Eur J Clin Invest 2010;40:950-9

- Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 2009;461:399-401

- Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet 2009;41:1105-9

- Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet 2009;41:1100-4

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Health technology appraisal - Peginterferon alfa and ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C (part-review of TA75 and TA106). London, UK: NICE, 2009

- Sullivan JC, De Meyer S, Bartels DJ, et al. Evolution of treatment-emergent variants in telaprevir phase 3 clinical trials. Europen Association for the Study of the Liver, 2011

- Levin J. Telaprevir resistance disappears in 89% of patients: Long-term follow-up of patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with telaprevir in combination with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin: interim analysis from the EXTEND study. Boston, MA: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, 2010