Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate total annual all-cause, gastrointestinal-related, and symptom-related healthcare costs among chronic constipation (CC) patients and estimate incremental all-cause healthcare costs of CC patients relative to matched controls.

Methods:

Patients aged ≥18 years with continuous medical and pharmacy benefit eligibility in 2010 were identified from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database. CC patients had ≥2 medical claims for constipation (ICD-9-CM code 564.0x) ≥90 days apart or ≥1 medical claim for constipation plus ≥1 constipation-related pharmacy claim ≥90 days apart, and no medical claims for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Sub-groups with and without abdominal symptoms were classified according to the presence/absence of abdominal pain (ICD-9-CM code 789.0x) and bloating (ICD-9-CM code 787.3x). Controls without claims for constipation, abdominal pain, bloating, or IBS or constipation-related prescriptions were randomly selected and matched 1:1 with CC patients on age, gender, health plan region, and plan type. Generalized linear models with bootstrapping evaluated incremental all-cause costs attributable to CC, adjusting for demographics and comorbidities.

Results:

Overall, 14,854 patients (n = 7427 each in CC and control groups) were identified (mean age = 59 years; 75.4% female). Mean annual all-cause costs for CC patients were $11,991 (2010 USD), with nearly half (44.8%) attributable to outpatient services, including physician office visits and other outpatient services (10.0% and 34.8%, respectively). GI-related costs comprised 33.7% of total all-cause costs. Symptom-related costs accounted for 10.5%, primarily driven by costs of other outpatient services (50.6%). Adjusted incremental all-cause costs associated with CC were $3508 per patient per year ($4446 for CC with abdominal symptoms; $2783 for CC without abdominal symptoms), of which 81.0% were from medical services. Incremental cost estimates may be over- or under-estimated due to classification based on claims.

Conclusions:

CC imposes a substantial burden in direct healthcare costs in a commercially insured population, mainly attributable to greater use of medical services.

Introduction

Chronic constipation (CC) is a commonly occurring functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder (FGID) and is characterized by infrequent bowel movements, hard or lumpy stools, straining, and a sensation of incomplete rectal evacuationCitation1. Symptoms of CC can include both bowel (infrequent bowel movements, hard stools, straining during defecation, a sense of incomplete evacuation) and abdominal (bloating, discomfort, pain) symptoms. Symptom criteria developed by the Rome Foundation are considered the diagnostic gold standard for FGIDs and provide criteria for the identification of patients with functional constipation, also referred to as CCCitation2. The Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional constipation include: (1) two or more of the following: straining during at least 25% of bowel movements, lumpy or hard stools in at least 25% of bowel movements, sensation of incomplete evacuation in at least 25% of bowel movements, manual maneuvers to facilitate at least 25% of bowel movements, and fewer than three bowel movements per week; (2) loose stools rarely present without the use of laxatives; and (3) insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), with criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months and symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosisCitation2.

Estimates of the prevalence of constipation range from 12–19% among adults in the US, with most estimates ∼15%Citation3. The prevalence of CC is estimated to increase with age and occur more frequently in women than menCitation4,Citation5. The distinction between constipation and CC is important when evaluating the economic impact of these conditions. Episodes of acute or occasional constipation (‘irregularity’) not resulting from an organic cause or functional GI disorder generally respond well to diet, lifestyle, and/or short-term medical management, and resolve quickly, while CC typically requires prolonged management of symptomsCitation6,Citation7 that may place a measurable economic burden on patients and the healthcare system. However, previous studies have only assessed the economic burden associated with constipation without regard to chronicityCitation8–10. Furthermore, no studies have assessed costs specifically for CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms.

Nyrop et al.Citation8 identified patients with constipation through a chart review and estimated the average annual direct healthcare costs of constipation patients to be $9117 (in 2010 USD) based on administrative claims data from a US health maintenance organization (HMO). However, this study only provided crude estimates of costs based on patients’ claims data without adjustment for potential confounding factors. Choung et al.Citation9 estimated the incremental medical costs for women with constipation identified from a community-based population in Olmsted County, Minnesota, and found direct costs for those with constipation to be more than twice that of age-matched controls over a 15-year period. Mitra et al.Citation10 estimated incremental charges to be $7949 (in 2010 USD) higher for constipation patients relative to age- and gender-matched controls. However, this study used charges as a proxy for costs, which do not reflect actual costs of healthcare resources used to deliver care, and classified cases based on only one medical claim for constipation, which may have resulted in the inclusion of estimates for both acute episodes of constipation and CC. This study also utilized an incidence-based approach to assess burden of illness, which more likely reflected the average cost of illness during the peri-diagnostic period. For chronic conditions, such as CC, a prevalence-based approach may be more suitable for informing payers of the total economic burden of disease since it characterizes the average annual cost per patient for all patients with the disease within a given timeframeCitation11. Another study assessing the impact of CC based on the 2007 US National Health and Wellness Survey found CC patients reported greater healthcare resource utilization than matched controlsCitation12, but did not extend assessment to healthcare costs.

Given the limited availability of data specific to the economic burden associated with CC, the objective of this study was to conduct a prevalence-based cost-of-illness analysis for CC from a commercial payer perspective. Specifically, this study used the total cost approach to estimate the total annual all-cause, GI-related, and symptom-related healthcare costs among CC patients seeking medical care and the incremental cost approach to estimate the incremental annual all-cause healthcare costs of CC patients relative to matched controls. As some CC patients may also experience symptoms of abdominal pain and bloating, total annual healthcare costs were also assessed among sub-groups of CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms to assess the impact of these symptoms on healthcare costs.

Patients and methods

Data source

This study utilized medical, pharmacy, and eligibility claims data extracted from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database (HIRD), which consists of administrative claims of ∼44 million members from 14 geographically-dispersed US health plans. Overall, demographic characteristics of the HIRD population are generally comparable with the US Census data (American Community Survey) in terms of age and gender. However, since many HIRD members include working individuals and their dependents with employer-provided health insurance, the HIRD population tends to be slightly younger, and individuals over 65 years of age tend to be under-represented.

All data used in this observational study were de-identified and accessed with protocols compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Patient confidentiality was preserved and the anonymity of all patient data was safeguarded throughout the study. No waiver of informed consent was required from an institutional review board.

Study design

This study was a retrospective administrative claims database analysis of a commercially insured population in the US. Given the chronic nature of CC, with patients often experiencing symptoms over long periods of time, a prevalence-based, rather than an incidence-based approach was used to identify the target sample and estimate the economic burden of illness from a payer perspectiveCitation11. A 1-year timeframe for claims eligibility was selected to assess the annual costs of CC, including CC with and without abdominal symptoms. The study period was defined as January 1, 2010 through December 31, 2010 based on the most recent calendar-year data available at the time the study was conducted. Two cost of illness approaches were used to estimate the costs of CC. The total cost approach assessed the sum of all-cause or disease-specific healthcare costs for patients with CC. The incremental cost approach estimated the excess all-cause costs attributable solely to the presence of CC by comparing CC patients with matched controlsCitation13. Together, these two approaches provided a more thorough assessment of the costs of illness of CC.

Study sample

Patients aged 18 years or older with 12 months continuous eligibility for medical and pharmacy benefits for the 2010 calendar year were identified for analysis. Considering the limitations of administrative claims database analyses, including the lack of an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code specifically for CC and the fact that ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for functional constipation may not sufficiently identify CC patients, detailed exploratory analyses were conducted to refine the patient identification criteria for this study and mitigate the risk of misclassification. These exploratory analyses were conducted prior to finalization of the study protocol and execution of analyses of costs in CC patients and controls and were guided by advice from gastroenterologists regarding the selection of potential inclusion and exclusion criteria. The impact of these criteria on the size of the study sample was evaluated based on descriptive analyses assessing the number of patients with at least one or two medical claims for constipation, abdominal pain, bloating, and other GI conditions, and the number of patients with pharmacy claims for constipation-related prescriptions (e.g., stimulant laxatives, osmotic laxatives, etc.). In addition, the number of days between medical and/or pharmacy claims for constipation and constipation-related prescriptions was evaluated to determine whether and what defined time-window between claims events would be appropriate to reliably identify patients with CC. Gastroenterologists were consulted to evaluate and approve the final inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Based on results of the exploratory analyses and clinical opinion, the overall CC group included CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms classified according to the presence or absence of abdominal symptoms (i.e., abdominal pain and bloating) as follows:

CC patients with abdominal symptoms

Patients were required to have: (1) ≥2 medical claims for constipation (ICD-9-CM code 564.0x) at least 90 days apart in 2010; or ≥1 medical claim for constipation plus ≥1 pharmacy claim for a constipation-related prescription (including lubiprostone, stimulant laxatives, osmotic laxatives, or stool softeners) at least 90 days apart in 2010, and (2) ≥1 medical claim for abdominal pain (ICD-9-CD code 789.0x) and/or bloating (ICD-9-CM code 787.3x) in 2010.

CC patients without abdominal symptoms

Patients were required to have: (1) ≥2 medical claims for constipation at least 90 days apart in 2010 or ≥1 medical claim for constipation plus ≥1 pharmacy claim for a constipation-related prescription at least 90 days apart in 2010, and (2) no medical claims for abdominal pain or bloating in 2010.

To avoid confounding of estimates by IBS, chronic diarrhea, drug-induced constipation, or other GI conditions or medications that may affect GI system function, exclusion criteria were defined and applied based on a review of previous studiesCitation5,Citation8,Citation10, clinical opinion, and results of the exploratory analyses. Patients were also excluded if they had one or more medical claims for any conditions that may be misdiagnosed as CC (e.g., GI malignancy, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, vascular insufficiency of intestine, intestinal malabsorption, diverticulitis) or that may present with some symptoms similar to CC (e.g., multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, diabetic neuropathy, pancreatitis) (see for exclusion criteria).

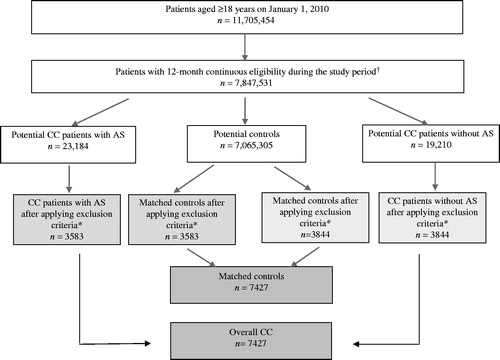

Figure 1. Patient identification flow chart. AS, abdominal symptoms; CC, chronic constipation. †739,832 patients did not qualify as potential CC patients or matched controls based on the study criteria. *Exclusion criteria: Patients with ≥1 medical claim for gastrointestinal malignancy, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, vascular insufficiency of intestine, intestinal malabsorption, diverticulitis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, diabetic neuropathy, or pancreatitis; Patients with ≥1 pharmacy claim for alosetron; Patients with ≥2 pharmacy claims for diphenoxylate hydrochloride/atropine sulfate on different dates during the study period; Patients with ≥2 medical claims for diarrhea occurring at least 30 days apart during the study period or with ≥1 medical claim for diarrhea plus ≥1 pharmacy claim for anti-diarrheal prescription occurring at least 30 days apart during the study period; Patients with ≥2 medical claims for gastritis, gastroenteritis, duodenitis, or uterine fibroids occurring at least 30 days apart during the study period; Patients with ≥120 days-supply of opioids over 6 consecutive monthsCitation14 during the study period.

Matched controls

To estimate the incremental costs attributable to CC, two separate control groups were randomly selected and matched with CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms in a 1:1 ratio based on age (±4 years), gender, health plan region (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West), and health plan type (preferred provider organization (PPO), health reimbursement account (HRA), health savings account (HSA), health maintenance organization (HMO), Medicare Advantage). Matching on health plan region and health plan type was conducted to control for differences in regional practice patterns and health plans that may confound estimates of the incremental healthcare costs of CC patients vs controls. For a few cases, wherein a matched control could not be identified from the same type of health plan within the same region, the control was identified within the same region but from a similar health plan type based on a pre-determined category of health plan types (i.e., PPO, HMO, consumer-driven health plan such as HRA and HSA, or other health plan types). The exclusion criteria applied to CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms were also applied to potential controls prior to matching. In addition, patients in the control groups could not have any medical claims for constipation, abdominal pain, bloating, or pharmacy claims for constipation-related prescriptions in 2010.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures were annual healthcare costs, including all-cause, GI-related, and symptom-related costs. All-cause healthcare costs were defined as the sum of health plan-paid and patient-paid direct healthcare costs incurred from all medical services and pharmacy claims associated with any condition or prescription during the study period. GI-related healthcare costs consisted of health plan-paid and patient-paid costs associated with GI-related conditions, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), esophagitis, dyspepsia, gallbladder or biliary disease, GI hemorrhage, hemorrhoids, constipation, abdominal pain, and bloating. These conditions, selected based on clinical consultation and a review of relevant literatureCitation10, are commonly assessed GI comorbidities among CC patients. Symptom-related costs were defined as health plan-paid and patient-paid costs associated with constipation, abdominal pain, or bloating for CC patients with abdominal symptoms and health plan-paid and patient-paid costs associated with constipation for CC patients without abdominal symptoms.

All-cause medical services were defined as healthcare resource utilization associated with any condition and included inpatient admissions, emergency department (ED) visits, physician office visits, and other outpatient services, for instance, diagnostic tests, outpatient procedures, laboratory tests, radiology services, and non-pharmacological therapies. All-cause prescription use was calculated as the mean number of standardized monthly all-cause prescription fills derived by dividing the annual days-supply of each prescription by 30 days.

Patients’ co-morbid conditions were measured using the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI) score, a claims-based measure of overall disease burden based on the occurrence of 30 co-morbid conditions of interest identified using the ICD-9-CM coding manualCitation15. In addition to the ECI, nine general co-morbidities (i.e., insomnia, malaise and fatigue, functional pain disorders, headache, hyperlipidemia, urinary tract infection, anxiety, dysuria, myalgia, and myositis) and six GI-related comorbidities (i.e., GERD, esophagitis, dyspepsia, gallbladder, GI hemorrhage, hemorrhoids) not included in the ECI were also assessed. These additional co-morbidities were identified as common co-morbid conditions of CC based on expert clinical opinion.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive analyses, mean, standard deviation (SD), and median were reported for continuous variables. Frequency and percentages were reported for categorical variables. To compare CC patients and matched controls, McNemar’s tests were used for categorical variables, such as gender and presence of co-morbid conditions, and non-parametric bootstrap estimation and t-tests were used for continuous variables, such as all-cause costs.

Generalized linear models (GLMs) were used to assess the incremental all-cause healthcare costs attributable to CC after adjusting for demographics, ECI score, and general and GI-related comorbidities not included in the ECI score to ensure isolation of incremental costs attributable to CC. Diagnostic tests were conducted to evaluate the distribution of costs. For each of the GLMs, the modified Park test was used to determine the appropriate familyCitation16, and the Pregibon link test, modified Hosmer and Lemeshow test, and Pearson’s correlation test were used to select the appropriate link functionCitation17. Adjusted incremental medical and prescription costs were estimated using the method of recycled predictionsCitation18. Non-parametric bootstrapping was used to assess the statistical significance of these incremental cost estimates. Sub-group analyses were performed among CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms utilizing the same methods outlined above.

All costs are reported in 2010 US dollars. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. All data analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 14,854 patients (n = 7427 each for the overall CC and matched control groups) met the study inclusion criteria. Among the overall CC group, 48.2% (n = 3583) were classified as CC patients with abdominal symptoms, and 51.8% (n = 3844) were classified as CC patients without abdominal symptoms (). The mean age among the total study sample was 59 ( ± 21) years, 75.4% were female, and 71.7% were covered by a PPO health plan (). Within the sub-groups, CC patients with abdominal symptoms were relatively younger (56 years vs 61 years) and consisted of a greater percentage of women (77.0% vs 73.9%) compared with CC patients without abdominal symptoms.

Table 1. Demographica and clinical characteristics of CC patients and corresponding matched controls.

Compared with matched controls, patients in the overall CC group had significantly greater morbidity as reflected by a higher mean ECI score (2.2 vs 1.0, p < 0.01) and had a significantly higher percentage of patients with general and GI-related co-morbidities and prescriptions filled (). Similar findings were observed among CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms vs their matched controls ().

Total costs of CC

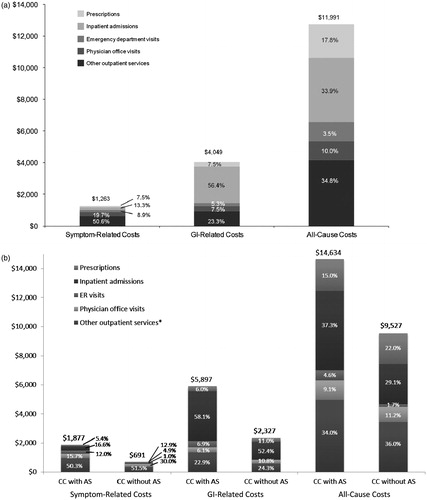

show the total annual all-cause, GI-related, and symptom-related costs for patients within the overall CC group and the abdominal symptom sub-groups. Total annual all-cause healthcare costs for overall CC patients were $11,991 (). Nearly half (44.8%) of these costs were due to other outpatient services and physician office visits (34.8% and 10.0%, respectively), with remaining costs attributable to inpatient hospitalizations (33.9%), prescriptions (17.8%), and ED visits (3.5%). Of the total all-cause costs, overall CC patients incurred $4049 (33.7%) in costs attributable to GI-related conditions and $1263 (10.5%) in symptom-related costs. Other outpatient services were the primary driver of symptom-related costs (50.6%), of which nearly half were for diagnostic tests and procedures, such as endoscopies.

Figure 2. Mean annual medical and prescription costs among (a) all CC patients, and (b) CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms (in 2010 USD). AS, abdominal symptoms; CC, chronic constipation; GI, gastrointestinal. Note: Symptom-related costs included costs related to constipation, abdominal pain, or bloating for CC patients with abdominal symptoms and costs related to constipation alone for CC patients without abdominal symptoms. *Other outpatient services mainly included diagnostic tests, outpatient procedures, laboratory tests, radiology services, or non-pharmaceutical therapies.

Total annual all-cause costs for CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms were $14,635 and $9527, respectively (). Nearly half of the costs for both sub-groups were due to physician office visits and other outpatient services (43.1% for CC patients with abdominal symptoms, 47.2% for CC patients without abdominal symptoms). Other outpatient services were again the primary driver of symptom-related costs at 50.3% of costs for CC patients with abdominal symptoms (over half of which were for diagnostic tests and procedures), and 51.5% of costs for CC patients without abdominal symptoms (over a quarter of which were for diagnostic tests and procedures).

Incremental costs of CC

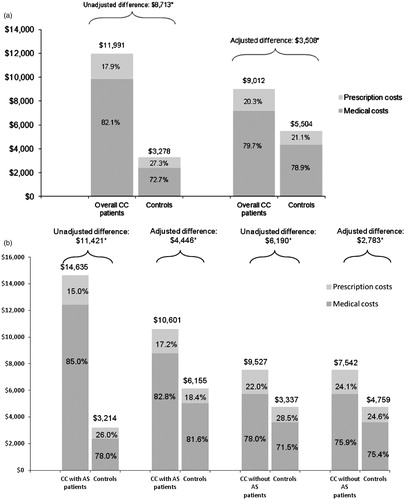

Patients in the overall CC group incurred $8713 more in unadjusted total all-cause costs than matched controls (p < 0.01) (), with an incremental difference of $7465 (85.7%) from medical costs and $1248 (14.3%) from prescription costs. Specifically, overall CC patients incurred $3294 (p < 0.01) more in unadjusted all-cause hospitalization costs, $3063 (p < 0.01) more in costs for other outpatient services, $776 (p < 0.01) more in costs for physician office visits, and $332 (p < 0.01) more in costs for ED visits compared with matched controls.

Figure 3. Unadjusted and adjusted mean medical and prescription costs (in 2010 US dollars) among (a) all CC patients and matched controls, and (b) CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms and matched controls. AS, abdominal symptoms; CC, chronic constipation. *Significant at p < 0.01 from non-parametric bootstrap estimation with t-tests, with 3000 replicates generated by randomly drawing samples from the total population clustered by the matched identifier.

These cost differences were driven by both a higher rate of use of these services as well as higher frequency of utilization among users (data not shown). Compared with matched controls, the overall CC group had a significantly higher percentage of patients with hospitalizations (25.1% vs 8.1%, p < 0.01), ED visits (30.2% vs 10.9%, p < 0.01), physician office visits (96.7% vs 74.5%, p < 0.01), other outpatient services (97.6% vs 71.4%, p < 0.01), and prescription fills (79.0% vs 59.7%, p < 0.01) for any reason in 2010. Other outpatient services were the primary driver of incremental costs.

After adjusting for demographic characteristics and co-morbidities, the incremental total all-cause healthcare costs associated with CC were $3508 ($9012 vs $5504, p < 0.01) (), of which 81.0% was from medical costs ($7182 vs $4342, p < 0.01) and 19.0% was from prescription costs ($1830 vs $1162, p < 0.01).

Significantly higher total unadjusted all-cause costs were also found for the abdominal symptom sub-groups compared with their matched controls. Sub-group analyses indicated both CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms used significantly more medical services and filled more prescriptions than their matched controls (data not shown). After adjusting for demographic characteristics and co-morbidities, incremental annual all-cause costs for CC patients with abdominal symptoms were $4446 ($10,601 vs $6155, p < 0.01), of which 84.6% was from medical costs (). Among CC patients without abdominal symptoms, incremental costs were $2783 ($7542 vs $4759, p < 0.01), with 76.7% from medical costs ().

Discussion

This study is one of the first to assess direct annual healthcare costs specific to CC and demonstrate the significantly incremental all-cause costs associated with this condition, even after controlling for demographic characteristics and general and GI-related co-morbidities. To better identify CC patients seeking medical care and controls, rigorous exploratory analyses were conducted to determine appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria, and an exact matching method was used for selecting matched controls to ensure their age, gender, health plan region, and health plan types were as similar as possible to those of CC patients. Two cost of illness approaches were utilized to assess both total and incremental costs of CC to thoroughly evaluate the burden associated with this condition. Furthermore, an extensive list of evidence-based co-morbid conditions was adjusted for in the multivariable models to isolate the incremental costs of CC, while sub-group analyses were conducted to further assess the economic burden among CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms.

Patients in the overall CC group incurred significantly higher adjusted medical and pharmacy costs than matched controls. Among the abdominal symptom sub-groups, incremental costs were ∼1.6-times higher for CC patients with abdominal symptoms vs CC patients without abdominal symptoms. Incremental costs associated with CC were primarily driven by costs associated with more frequent use of medical services, which accounted for 81.0% of total all-cause costs for overall CC patients, 84.6% of costs for CC patients with abdominal symptoms, and 76.7% of costs for CC patients without abdominal symptoms. Physician office visits and other outpatient services were the most frequently utilized medical services attributed to any condition, with significantly higher average use among patients with CC both overall and among the abdominal symptom sub-groups compared with matched controls.

While the economic impact of CC and associated abdominal symptoms are noteworthy for patients and the healthcare system, this condition is often overlooked. The magnitude of the burden of CC can be put into perspective by comparing it with the economic burden of other chronic conditions, such as migraine and asthma, although such comparisons should be made with caution as methodologies differ across studies and other studies do not always include all types of costs. These comparisons are informative because migraine and asthma are both chronic, symptomatic conditions with a significant impact on patient health that do not clinically overlap with functional GI disease. Similar to CC, migraine also disproportionately affects more women than men, with treatment consisting of both over-the-counter medications and prescriptionsCitation19. The total annual per-patient costs of CC found in this study are comparable with annual costs estimated for migraine patientsCitation20 and comparable or higher than those for patients with asthma, although cost drivers may vary across therapeutic areasCitation21,Citation22. Mitra et al.Citation10 also used migraine as a benchmark and found the adjusted 12-month all-cause healthcare charges for patients with migraine to be much lower than for patients with constipation. These comparisons indicate CC may be more costly to the healthcare system than other chronic conditions for which there tends to be higher awareness among payers, further emphasizing the need to reduce costs associated with CC.

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. As with all retrospective claims database analyses, definitive diagnoses are not available and, to our knowledge, no claims algorithm validation studies have been conducted for CC. Exploratory analyses were conducted to better identify CC patients in this study and mitigate misclassification. However, classification of patients with CC required assumptions based on available diagnostic codes and pharmacy prescriptions, leading to potential classification bias that may have affected the cost estimates. Further research should be undertaken to validate the identification of CC patients in claims through a medical chart review. It should also be noted that patients with CC included in the study database were commercially insured, thereby limiting the generalizability of this study’s findings to other populations, such as uninsured individuals or Medicaid recipients. Future studies should examine the economic burden of CC in other patient populations.

A few caveats that may have influenced our incremental cost estimates in either direction also deserve mention. Given the sample inclusion criteria (i.e., ≥2 medical claims for constipation or ≥1 medical claim for constipation plus ≥1 pharmacy claim for a constipation-related prescription at least 90 days apart), it is possible CC patients identified in the claims were those seeking more frequent medical care and, hence, may have higher healthcare costs, thus resulting in an over-estimation of incremental costs in our study. Furthermore, given the chronic and cyclical nature of CC, patients who were previously diagnosed and whose symptoms are under control may not have had claims for constipation within the study period, in which case the costs for these patients may be lower and our incremental cost estimates may be over-estimated. At the same time, to the extent that we fail to capture CC patients who were under-coded (e.g., once an initial diagnosis has been made, patients were only coded for constipation once in the claims and no additional constipation claims were listed), then the exclusion of such patients should not affect our estimates. Also, our failure to capture patients who were misdiagnosed or under-treated may result in our results being an under-estimate of the true incremental costs of CC to the extent that such patients consume more resources related to specialist office visits and diagnostic tests and procedures.

While this study attempted to be comprehensive in terms of matching patients on demographics and health plan type and controlling for ECI score and 15 other general and GI-related comorbidities, it is possible that our incremental cost estimates may have still been affected by residual confounding of unmeasured variables given the large differences observed in the presence of some co-morbidities among CC patients and controls. While the causal order is not established in the literature, to the extent that CC affects the risk, persistence, or severity of co-morbidities, such as depression or anxiety, the costs associated with these co-morbidities may be considered long-term indirect effects associated with CC and, thus, appropriately considered costs of patients with CC. Accordingly, our approach of controlling for such conditions may have resulted in an under-estimate of the true costs associated with CC. The above issues of under-coding in claims data as well as the influence of CC on the persistence and severity of co-morbidities may explain our finding of a large proportion of all-cause incremental costs in our study being non-symptom-related.

Finally, the results of this study may also under-estimate the burden of CC given cost estimates only accounted for direct healthcare costs for services reimbursed by commercial insurers. Indirect costs were not included as relevant data cannot be captured from administrative claims. However, reduced productivity may also have a substantial economic impact on CC patients and employers and should be assessed furtherCitation11. Direct cost estimates in this study could also be under-estimated due to a lack of data on over-the-counter medications or complementary/alternative medicines commonly used by CC patients to self-treat their symptoms, which are often outside of health insurance coverage and not captured in administrative claims data. Furthermore, costs for patients aged 65 years and older could be under-estimated because costs paid by other payers (e.g., co-ordination of benefits) for this population were not included in this study. The overall implications of these various caveats on the directionality of our estimates are unknown.

Conclusions

CC imposes a significant economic burden in direct healthcare costs, even after controlling for general and GI-related comorbidities. The majority of incremental costs are attributable to a greater use of medical services among CC patients, both overall and among sub-groups of CC patients with and without abdominal symptoms. Symptom-related costs were mainly driven by a greater use of physician office visits and other outpatient services. Further research should focus on the underlying factors driving increased medical resource use among patients with CC.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funding for this study was provided by Forest Research Institute and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals.

Declaration of financial relationships

JLB and RTC are employees of Forest Research Institute and own stock/stock options; WMS and PS are employees of Ironwood Pharmaceuticals and own stock/stock options; QC, HT, and JJS are employees of HealthCore, Inc., an independent research organization that received funding from Forest Research Institute and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals for the conduct of this study. JD has served as a consultant to Forest Research Institute, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and HealthCore Inc.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Steven J. Shiff, MD, and Douglas S. Levine, MD, for providing clinical consultation on patient identification criteria and disease co-morbidities, and Brennan Spiegel, MD, MSHS, for his advice and consultation in the design of this study.

References

- Johanson JF. Review of the treatment options for chronic constipation. Med Gen Med 2007;9:25

- Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480-91

- Higgins PD, Johnanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:750-9

- Chang L. Impact of chronic constipation and IBS. Adv Stud Med 2006;6:S49-57

- Lembo AJ, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1360-8

- World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines. Coping with common GI symptoms in the community—A global perspective on heartburn, constipation, bloating, and abdominal pain/discomfort. Milwaukee, WI, USA: World Gastroenterology Organisation. 2013. http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/assets/export/userfiles/2013_FINAL_Common%20GI%20Symptoms%20_long.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2013

- American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force. An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100(Suppl 1):S1-4

- Nyrop KA, Palsson OS, Levey RL, et al. Costs of health care for irritable bowel syndrome, chronic constipation, functional diarrhea and functional abdominal pain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;26:237-48

- Choung RS, Branda ME, Chitkara D, et al. Longitudinal direct costs associated with constipation in women. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33:251-60

- Mitra D, Davis KL, Baran RW. All-cause health care charges among managed care patients with constipation and comorbid irritable bowel syndrome. Postgrad Med 2011;123:122-32

- Segel JE. Cost of illness studies—A primer. Research Triangle Park, NC, USA: RTI International. 2006. http://www.amcp.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=12960. Accessed February 28, 2013

- Sun SX, DiBonaventura M, Purayidathil FW, et al. Impact of chronic constipation on health-related quality of life, work productivity, and healthcare resource use: an analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:2688-95

- Akobundu E, Ju J, Blatt L, et al. Cost-of-illness studies: a review of current methods. Pharmacoeconomics 2006;24:869-90

- Leider HL, Dhaliwal J, Davis EJ, et al. Healthcare costs and nonadherence among chronic opioid users. Am J Manag Care 2011;17:32-40.

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8-27

- Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. J Health Econ 2005;24:465-88

- Glick H, Doshi J. Applications of statistical considerations in health economic evaluation. Short course presented at: International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research 16th Annual International Meeting; May 22, 2011; Baltimore, MD

- Basu A, Rathouz PJ. Estimating marginal and incremental effects on health outcomes using flexible link and variance function models. Biostat 2005;6:93-109

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology 2007;68:343-9

- Hawkins K, Wang S, Rupnow M. Direct cost burden among insured US employees with migraine. Headache 2008;48:553-63

- Barnett SB, Nurmagambetoy TA. Costs of asthma in the United States: 2002-2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127:145-52

- Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan VH, Slejko JF, et al. The burden of adult asthma in the United States: Evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127:363-9