Abstract

Introduction:

Secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) is a major complication of end stage renal disease (ESRD). For the National Health Service (NHS) to make appropriate choices between medical and surgical management, it needs to understand the cost implications of each. A recent pilot study suggested that the current NHS healthcare resource group tariff for parathyroidectomy (PTX) (£2071 and £1859 in patients with and without complications, respectively) is not representative of the true costs of surgery in patients with SHPT.

Objective:

This study aims to provide an estimate of healthcare resources used to manage patients and estimate the cost of PTX in a UK tertiary care centre.

Methods:

Resource use was identified by combining data from the Proton renal database and routine hospital data for adults undergoing PTX for SHPT at the University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, from 2000–2008. Data were supplemented by a questionnaire, completed by clinicians in six centres across the UK. Costs were obtained from NHS reference costs, British National Formulary and published literature. Costs were applied for the pre-surgical, surgical, peri-surgical, and post-surgical periods so as to calculate the total cost associated with PTX.

Results:

One hundred and twenty-four patients (mean age = 51.0 years) were identified in the database and 79 from the questionnaires. The main costs identified in the database were the surgical stay (mean = £4066, SD = £,130), the first month post-discharge (£465, SD = £176), and 3 months prior to surgery (£399, SD = £188); the average total cost was £4932 (SD = £4129). From the questionnaires the total cost was £5459 (SD = £943). It is possible that the study was limited due to missing data within the database, as well as the possibility of recall bias associated with the clinicians completing the questionnaires.

Conclusion:

This analysis suggests that the costs associated with PTX in SHPT exceed the current NHS tariffs for PTX. The cost implications associated with PTX need to be considered in the context of clinical assessment and decision-making, but healthcare policy and planning may warrant review in the light of these results.

Introduction

Secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) is a major complication of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Loss of kidney function leads to phosphate retention, hypocalcaemia, and deficiency of 1,25 hydroxyvitamin D, which in turn causes excessive synthesis and secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH)Citation1,Citation2. Sustained hypersecretion of PTH is associated with an increase in parathyroid gland size. Thus, most untreated ESRD patients develop SHPT as a result of the kidney’s inability to maintain mineral homeostasisCitation3.

Conventional therapy for SHPT includes the control of serum phosphate with phosphate binders and control of PTH with vitamin D sterolsCitation4. In many cases this proves inadequate, and parathyroidectomy (PTX) surgery is requiredCitation5,Citation6. It is estimated that ∼25 UK centres currently carry out PTX surgery for secondary parathyroidism. The only published data available shows that, between 2001–2011, 110 members of the British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons (BAETS) performed 8619 parathyroid surgeries, including 846 PTX’s in renal patientsCitation7.

For the National Health Service (NHS) to make appropriate choices between medical and surgical management, it needs to understand thoroughly the cost implications of each. The UK utilises a healthcare service reimbursement system called Payment by Results (PbR)Citation8. This system uses healthcare resource groups (HRGs), which are similar to the widely used diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) and based on the average cost of treatment in previous years, known as the NHS Reference CostsCitation9. The NHS PbR National Tariff (2011–2012) for parathyroid procedures with complications was £2481 for electively admitted patients and £6202 for non-electively admitted patients (emergency admissions). A recent study undertaken by the University of Sheffield found that the true cost of an elective PTX at one centre in Sheffield was £6828Citation10, which also showed that the costs associated with PTX are not incurred solely from the procedure itself but also incurred prior to and post-surgery. This was a single centre study, so it may not accurately reflect the cost of PTX in the UK. Additional well-designed studies are required to determine whether the findings from Sheffield are representative across the UK.

This study was conducted to understand the healthcare resources used to manage patients, who undergo PTX surgery, and estimate the costs associated with PTX, prior to and post-surgery, and not just the cost of the surgical phase itself, across a number of centres in the UK.

Patients and methods

The study consisted of two stages: a detailed cost analysis using a database within the Cardiff and Vale NHS Trust’s renal unit followed by a clinician questionnaire on resource use sent to nephrologists and PTX surgeons at a number of UK renal transplant centres. The methods used were similar to a previous study conducted by Cardiff Research Consortium, providing a detailed bottom-up costing of peritoneal and haemodialysis across the UKCitation11.

The renal unit in Cardiff is based at the University Hospital of Wales (UHW), and covers south east, west, and parts of mid-Wales, serving ∼2.2 million people. The Proton renal system database was used to identify patients aged 18 and over who had undergone renal replacement therapy between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2008. This patient list was linked to the Cardiff and Vale NHS Trust routine database in order to identify previous and subsequent inpatient admissions.

The clinician questionnaire was developed using the data collected and analysed from the Cardiff database and validated using the experience of a consultant nephrologist and transplant surgeon, and a consultant endocrine surgeon at UHW prior to wider use. Of 29 renal centres across the UK approached to complete the questionnaire, six agreed to participate, at four centres a nephrologist and a surgeon completed the questionnaire, while at two centres the nephrologist completed the questionnaire. All of the centres were located at teaching hospitals in London, the South East, the Midlands, the North West, and Wales, covering a population of ∼7.8 million people, representing ∼12.4% of the UK and 14.0% of the England and Wales populationsCitation12.

Data collected from both the database and questionnaires were split into six phases: pre-surgical (3 months prior to surgery), surgical stay, peri-surgical (30 days post-discharge), and three post-surgical phases (1–12 months, 13–24 months, and 25–36 months post-discharge). Resource use was calculated for hospital visits, laboratory testing, and medications for each time period.

Hospital visits were categorized as either inpatient or outpatient visits. Laboratory testing included ultrasound, nuclear medicine, computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, electrocardiography (ECG), and assessment of PTH, calcium, full blood count, renal profile, liver profile, glucose levels, lipid levels, and calcium phosphate. Medications were grouped as calcium, vitamin D, calcium + vitamin D, phosphate binders, antibiotics, analgesics, and Cinacalcet (Mimpara®).

As this study was deemed an audit by South East Wales Research ethics Committee (REC reference number 10/WSE03/44), ethical approval was not required.

Costs

Cost data were identified from published sources for the UK in 2010–2011 GBP. Where 2010–2011 costs were not available, the costs were inflated using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI)Citation13.

Costs for the surgical stay were obtained from two sources: NHS Reference Costs 2011–2012Citation9 () and NHS PbR National Tariff 2011–2012Citation8 (). As these costs are all inclusive, no separate laboratory or medication costs were calculated for this phase.

Table 1. NHS reference costs 2011–2012Citation9.

Table 2. NHS payment by results, National tariff 2011–2012Citation8.

Table 3. Laboratory tests.

Table 4. Patient demographics.

As patients in the study were undergoing PTX following secondary hyperparathyroidism and end stage renal disease a relevant healthcare resource group (HRG)Citation14 code (KA03A: Parathyroid Procedures with complications) was identified. This was based on an OPCS-4.6 procedure code of B141 (Global parathyroidectomy and transposition of parathyroid tissue) combined with a renal specific ICD-10 diagnoses code (i.e. N185 – Chronic Kidney Disease, stage 5; E211 Secondary hyperparathyroidism, not elsewhere classified) implemented in the HRG local payment grouper. HRG code selection for PTX procedures was validated using expert clinician opinion.

The mean cost for a generic outpatient visit to hospital was identified as £147Citation15. Laboratory test costs were located from a number of published sources ()Citation9,Citation16,Citation17; where published costs were not available, costs were sourced from the Cardiff and Vale NHS Board. Medication costs were obtained from the British National Formulary (BNF) 63Citation18. Prescription information was only available within the Proton database, allowing calculation of cost per milligram for each individual drug for each patient, while under the care of the renal unit, relevant prescriptions from primary care and other secondary care treatments (i.e. outpatients) were not available. However, for the questionnaire analysis, costs were calculated as an average cost for each drug category (calcium = £0.03 per mg, vitamin D = £0.95 per µg, calcium + vitamin D = £0.0003 per mg, phosphate binders = £0.0006 per mg, antibiotics = £0.009 per mg, and analgesics = £0.02 per mg).

Table 5. Hospital visits, tests, and medications.

Due to the difference in the number of patients treated at each centre, it was not appropriate to use centre means for costing resources such as cost of medications or laboratory tests. Resource cost was, therefore, calculated per PTX patient per centre and then added together to calculate a total cost; this total cost was then divided by the total number of PTX patients to calculate a patient mean.

Where data from laboratory tests and medications were missing from the database, average values were imputed from the other patients. A comparison analysis between imputed values and null values showed that missing data had a negligible effect on these costs. Where data relating to other items (such as outpatient and General Practitioner (GP) appointments) were missing, they were addressed using the clinician questionnaire by both the nephrologist and the endocrine surgeon at UHW in Cardiff. Missing data only occurred in the pre- and post-surgical phases; no data relating to the surgical stay were missing. Where data were missing from the clinician questionnaires, or the data were ambiguous, the clinicians were contacted to clarify their responses. Where data were still missing, it was assumed that the missing data was truly missing and average values were imputed.

Results

Demographics

Between 2000 and 2008, 124 PTXs were identified from the renal database at the UHW in Cardiff, and 79 PTXs from the clinician questionnaires in 2010. Demographics were similar across centres (Table 4).

Pre-surgical phase

Outpatient data were not available for patients in the database; therefore, the number of hospital outpatient visits related to PTX in the 3 months prior to surgery was estimated by the clinician. The same approach was applied in the questionnaire. The clinician indicated that the database patients would visit the hospital once, while in the questionnaires it was estimated that patients visited 1.1 times (SD = 0.5, centre mean = 1.3) ().

A number of tests, such as ultrasound and nuclear medicine, were not undertaken in the database patients, while tests such as full blood count (71.8% of patients, 5.8 tests), renal profile (71.8%, 5.6 tests), and liver profile (71.8%, 4.9) were commonly undertaken in the majority of patients. From the questionnaires it could be seen that the most common tests undertaken were renal profile (100% of patients, 6.1 tests), full blood count (100%, 3.6), liver profile (100%, 3.3), and PTH tests (100%, 1.8).

Surgical stay

Database patients had a mean surgical stay of 5.6 days (SD = 7.4). Questionnaires indicated that patients had a mean surgical stay of 2.7 days (SD = 2.3).

In the database, the most commonly undertaken tests during the surgical stay were calcium (71.8% of patients, 12.2 tests) and liver profile (71.8%, 6.4) (). The most frequently undertaken tests identified from the questionnaires were full blood counts (75.0% of patients, 2.9 tests), liver profiles (70.8%, 2.5), and PTH testing (70.8%, 1.9).

No data were available on complications associated with surgery in the database. In the questionnaires severe complications were rare, with excessive bleeding occurring in 0.7% (SD = 0.8) of patients in a year, haematoma occurring in 0.8% (SD = 0.8), and damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve occurring in 0.2% (SD = 0.2) of PTX operations, amounting to 0.4, 0.5, and 0.1 complications annually.

Peri-surgical phase

Neither outpatient data nor GP data were available for patients in the 30-day peri-surgical phase in the database; therefore, the number of such visits related to PTX in the 30 days post-surgery was estimated by the clinician. It was estimated that patients visited hospital once and their GP once. From the questionnaires, patients had a mean of 7.2 outpatient visits (SD = 3.2, centre mean = 7.7) and 2.4 GP visits (SD = 0.0, centre mean = 12.0) ().

In the database patients, liver profile testing (61.3% of patients, 5.4 tests) and calcium testing (60.5%, 5.3) were the most common tests carried out. Liver profile (100%, 4.5) and renal profile (100%, 3.3) tests were the most frequent tests undertaken in the per-surgical phase identified by the questionnaires.

Post-surgical phase

Data relating to outpatient appointments in the post-surgical phase were not available in the database; the clinicians estimated that, in the 1–12 month post-discharge period, patients would have five outpatient appointments, with one per year in the next 2 years.

From the questionnaires the mean number of outpatient appointments 1–36 months post-discharge was estimated at 13.3 (centre mean = 13.3), with 3.2 GP appointments (centre mean = 16.0).

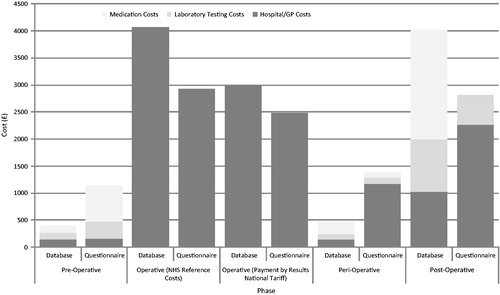

Cost analysis

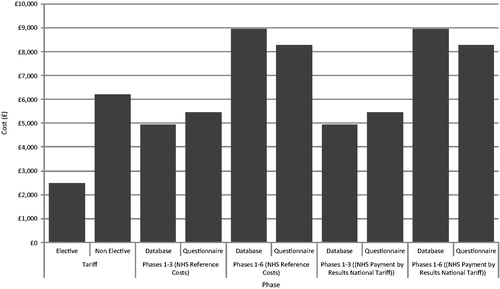

Using the NHS Reference Costs, the mean PTX-associated costs in the database amounted to £4932 (SD = £4129, median = £3992, range = £3124–£37,621) between the pre-surgical phase and peri-surgical phase (inclusive), and £8964 (SD = £5400, median = £7554, range = £4842–£40,379) when the 3 years post-surgical phase was included (). The main costs were incurred in the surgical stay (mean = £4066, SD = £4130, median = £3156, range = £2648–£37,075) which included all procedures, medications, and tests, although substantial costs were also incurred in the pre-surgical (mean = £399, SD = £164, median = £368, range = £193–£1824) and peri-surgical phases (mean = £465, SD = £176, median = £465, range = £186–£1111) (). From the questionnaires, the cost of PTX was £5459 (SD = £612, median = £5435, range = £4594–£6349) across the first three phases, and £8276 (SD = £807, median = £7988, range = £7000–£9369) when the 3 years post-surgical phase was included.

The mean cost of PTX using the NHS PbR National Tariff costs were £3847 (SD = £1185, median = £3355, range = £2957–£7573) in the database and £5515 (SD = £612, median = £4989, range = £4148–£5903) in the questionnaires (), with the 3-year post-surgical phase increasing these mean costs to £7683 (SD = £3650, median = £7111, range = £4675–£35,226) and £8332 (SD = £807, median = £7542, range = £6554–£8923) in the database and questionnaires, respectively.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that patients undergoing PTX in the UK are similar across centres with respect to age and modality of dialysis. However, there appeared to be variation in practice between centres prior to, during, and after surgery. During all phases, less medication seemed to be prescribed and fewer laboratory tests undertaken for Cardiff (database) patients than for patients at the other centres. This could be due to either variation in practice between centres, missing data in the database, or the difference in the method of collection between the database and questionnaires.

The variation in time from the first renal therapy to referral for surgery (24–87.4 months) highlights varying practice between renal surgeons in different centres, which may also lead to a variation in treatment. As outcomes data were not available, it was not possible to identify whether there were any differences in outcomes between patients referred early following ESRD and those referred late. Variation also existed in surgical practice, such as with the use of pre-surgical localization and with some surgeons favouring total PTX and some partial PTX.

The average length of surgical stay varied between centres from 1.6–6 days; in the Sheffield study, the surgical stay was 6.8 daysCitation10, while the BAETS report didn’t differentiate between those with primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism, but indicated that patients undergoing PTX generally had a post-surgical stay of less than 2 daysCitation7. With very few complications occurring, the variation in length of stay may be due to differences in practice, when the patient was admitted, the practice of non-weekend discharge, or due to patients remaining in hospital for further dialysis. It is also possible that this difference is due to the database containing data on provider spells (a total continuous stay in hospital), whereas it is possible that clinicians completing the questionnaire only estimate finished consultant episodes, where the length of stay is calculated as the time the patient is under that physician’s care, with the patient then being discharged into the care of another physician and not necessarily home.

It is possible that the lower levels of prescribing seen in the database during the operative phase, when compared to the questionnaires, were a result of clinicians prescribing the minimum amount needed while under their care, and then for adjustment to take place at outpatient follow-up.

The most variation between centres occurred in the 30-day peri-surgical phase and related to outpatient and GP visits. In Cardiff, it was estimated that patients would have one outpatient and one GP visit, but, across the UK, clinicians estimated that patients would have an average of 7.2 outpatient visits and 2.4 GP appointments.

The current NHS PbR National Tariff payment to hospitals for PTX in patients with complications is £2481 for elective admissions. Using NHS Reference Costs, the average cost of resource use associated with PTX in Cardiff was £4066 for the surgical stay alone, with pre-surgical costs of £399 and peri-surgical costs of £465, increasing the average total cost associated with PTX to £4932 per patient over the three phases of treatment. Using the NHS PbR National Tariff to cost the surgical stay, the average cost of surgery was £2983, giving a total cost of £3847 per patient.

Across the other UK centres, using the NHS Reference Costs the average cost of surgery was £2927, lower than that seen in Cardiff but still higher than the National Tariff, although also exclusive of the pre- and peri-surgical costs which increased the total cost of PTX to £5515. The costs observed across the UK centres consisted of higher pre-surgical medication costs and peri-surgical outpatient and GP visit costs. This difference may be due to variation in clinical practice, but may also be due to missing data in Cardiff.

It is interesting to note that, during both the pre-operative and peri-operative phases, the costs within the database were lower than from the questionnaires, but in the 3-year post-surgical phase the reverse was true. This could be due to the questionnaires reporting optimal treatment patterns rather than actual treatment patterns, although the main discrepancy occurs in the post-operative phase in relation to medication usage where reporting was limited in the questionnaires.

The costs generated in the study in Sheffield came to £5772, but it is not clear what costs were included and excluded in the study. However, like the Cardiff study, the cost of PTX exceeded the tariff paid to the hospital.

The variation in costs between centres could be indicative of differences in practice, or due to missing data. Variations in clinical practice could highlight the lack of standardized guidelines for PTX in the UK. The variation in referral times may show a need for more collaboration between departments and between the renal and PTX surgeons, although, in this study, it has not been possible to assess whether there are any differences in outcomes between early and late referrals. The differences observed may also be due to the relatively small number of patients included in both the database and the questionnaires.

Missing data from the Cardiff Proton database has been addressed by imputing average values based on available data. Regardless of this, in comparing laboratory testing and medication data from centres across the UK, it would appear that the Cardiff data may under-estimate the true cost associated with PTX.

As the questionnaires were intended to collect estimates based on clinician experience, it is possible that they reported optimal treatment rather than actual treatment and/or that recall bias existed. This is especially likely in relation to the estimated hospital length of stay, which may also be affected by whether the patient was followed up by the surgeon post-surgery. It is possible that variation in the estimates of outpatient and GP visits could be due to clinicians estimating all visits and not just those related to PTX. Only one centre estimated visits to the GP, with all others leaving this estimate unpopulated.

Questionnaire data was submitted by 11 clinicians from six centres out of the 29 approached. When comparing renal registryCitation19 data from the centres that completed the questionnaire and those that did not, there were no significant differences, with respect to the following: ethnicity (p = 0.880), the proportion of dialysis modality (haemodialysis (HD) or peritoneal dialysis(PD)) (p = 0.783), the mean PTH level in both those receiving HD (p = 0.478) or PD (p = 0.324), the mean calcium level in both those receiving HD (p = 0.683) or PD (p = 0.317), or the mean phosphate level in both those receiving HD (p = 0.817) or PD (p = 0.878). There was a small, but significant difference in the median age of the centres (p = 0.048, mean difference = 2.56 years; CI = 0.029–5.088).

Conclusion

This study suggests that the true cost associated with PTX in patients with SHPT, due to ESRD, exceeds the NHS PbR National Tariff of £2481. This supports the disparity between actual resource use (i.e. cost) and current reference-based costs indicated by the Sheffield study. While this would not be expected to influence clinical decisions, it is an important consideration given current budgetary constraints that exist in the NHS. A better understanding of the cost implications would allow for better healthcare planning and policy decision-making, with a need for payers and HTA agencies to take into account that the current HRG tariff may significantly under-estimate the cost of surgery, and that it may not be representative of the total cost associated with PTX, which includes pre-surgical, surgical, peri-surgical, and post-surgical costs.

This study also suggests that there may be a lack of clear clinical guidance with respect to PTX given clinical practice is highly variable between centres. By creating standardized guidelines, costs would be easier to identify and streamline.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Amgen Ltd., of whom employees helped in the design and undertaking of the study and the writing of the manuscript. All authors were involved in the conduct of the study and the writing and editing of this manuscript. Lucy Hyatt of Amgen (Europe) GmbH provided additional editorial assistance once the draft was complete.

Declaration of financial relationships

EC is an employee of Amgen Ltd., RDP and GC acted as paid consultants, and DSC and KB acted as unpaid consultants to Amgen Ltd. No other conflicts of interest exist.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance and advice given by Dr James Fotheringham with commentary on the study report.

Previous presentation

These data were presented as ‘Assessment of the Resource Use and Costs Associated with Parathyroidectomy Surgery for Secondary Hyperparathyroidism in End Stage Renal Disease in the UK’ at ISPOR 15th Annual European Congress, 3–7 November 2012, Berlin.

References

- Drueke TB. Cell biology of parathyroid gland hyperplasia in chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000;11:1141-52

- Fukagawa M, Nakanishi S, Kazama JJ. Basic and clinical aspects of parathyroid hyperplasia in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2006;70(102 Suppl):S3-7

- Joy MS, Karagiannis PC, Peyerl FW. Outcomes of secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic kidney disease and the direct costs of treatment. J Manag Care Pharm 2007;13:397-411

- Drueke TB, Ritz E. Treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism in CKD patients with cinacalcet and/or vitamin D derivatives. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:234-41

- Kestenbaum B, Andress DL, Schwartz SM, et al. Survival following parathyroidectomy among United States dialysis patients. Kidney Int 2004;66:2010-16

- Kestenbaum B, Seliger SL, Gillen DL, et al. Parathyroidectomy rates among United States dialysis patients: 1990-1999. Kidney Int 2004;65:282-8

- The British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons. Fourth National Audit Report. Henley-on-Thames: Dendrite Clinical Systems Ltd, 2012

- Department of Health. Payment by Results National Tariffs 2011–2012. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_125398.xls. Accessed April 2013

- Department of Health. NHS Reference Costs 2011–12. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-reference-costs-financial-year-2011-to-2012. Accessed April 2013

- Fotheringham J, Duenas A, Rawdin A, et al. Assessing the cost of parathyroidectomy as a treatment for uncontrolled secondary hyperparathyroidism in stage 5 chronic kidney disease. Poster presented at ERA- EDTA congress in Munich: June, 2010

- Baboolal K, McEwan P, Sondhi S, et al. The cost of renal dialysis in a UK setting–a multicentre study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:1982-9

- Office of National Statistics (ONS). 2010-Based National Population Projections. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/npp/national-population-projections/2010-based-projections/rep-2010-based-npp-results-summary.html#tab-Results. Accessed March 2013

- Office of National Statistics (ONS). Consumer Price Indices available from the Office of National Statistics. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/cpi/consumer-price-indices/index.html. Accessed March 2013

- NHS Information Centre. HRG4 2010/11 Reference Costs Grouper Documentation HRG4 2010/11 Reference Costs Grouper Chapter Listings

- Curtis. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2011. University of Kent. http://www.pssru.ac.uk/archive/pdf/uc/uc2011/uc2011.pdf. Accessed March 2013

- Garside R, Pitt M, Anderson R, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cinacalcet for secondary hyperparathyroidism in end-stage renal disease patients on dialysis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2007;11(18):iii, xi-xiii, 1-167

- Kidney Care. Developing robust reference costs for kidney transplants Update. 2011. http://www.kidneycare.nhs.uk/Library/DevelopingRobustreferencereportWEBFINAL.pdf. Accessed April 2012

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (online). 2012. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press, http://www.medicinescomplete.com. Accessed April 2012

- Pruthi R, Pitcher D, Dawnay A. UK Renal Registry 14th Annual Report: Chapter 9 Biochemical variables amongst UK adult dialysis patients in 2010: National and centre-specific analyses. 2011. http://www.renalreg.com/Reports/2011.html. Accessed October 2013