Abstract

Background:

To assess the cost-effectiveness of the Disease Modifying Treatments (DMT), Glatiramer Acetate (GA) and Interferon beta-1a (IFN) in monotherapy alone and in combination for the prevention of relapses among Spanish patients aged between 18–60 years old with established Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis (RRMS).

Methods:

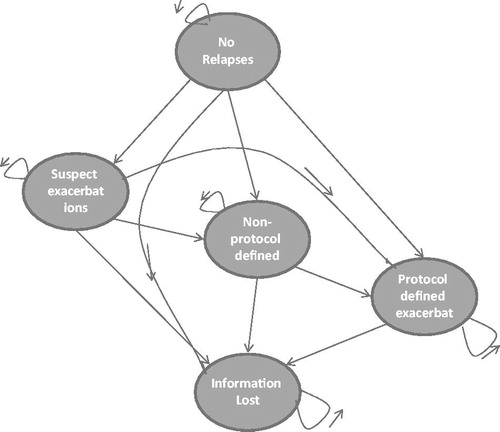

A Markov model was developed to represent the transition of a cohort of patients over a 10 year period using the perspective of the Spanish National Health Service (NHS). The model considered five different health states with 1-year cycles including without relapse, patients with suspect, non-protocol defined and protocol defined exacerbations, as well as a category information lost. Efficacy data was obtained from the 3-year CombiRx Study. Costs were reported in 2013 Euros and a 3% discount rate was applied for health and benefits. Deterministic results were presented as the annual treatment cost for the number of relapses. A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was performed to test the robustness of the model.

Results:

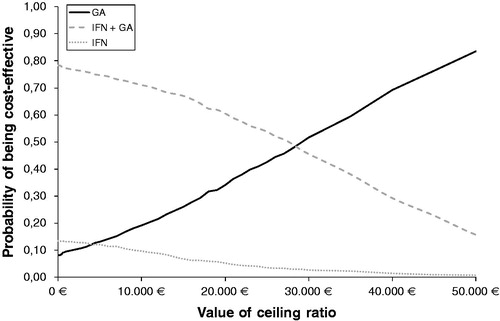

Deterministic results showed that the expected annual cost per patient was lower when treated with GA (€13,843) compared with IFN (€15,589) and the combined treatment with IFN + GA (€21,539). The annual number of relapses were lower in the GA cohort with 3.81 vs 4.18 in the IFN cohort and 4.08 in the cohort treated with IFN + GA. Results from probabilistic sensitivity analysis showed that GA has a higher probability of being cost-effective than treatment with IFN or IFN + GA for threshold values from €28,000 onwards, independent of the maximum that the Spanish NHS is willing to pay for avoiding relapses.

Conclusion:

GA was shown to be a cost-effective treatment option for the prevention of relapses in Spanish patients diagnosed with RRMS. When GA in monotherapy is compared with INF in monotherapy and IFN + GA combined, it may be concluded that the first is the dominant strategy.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating and degenerative disease of the central nervous systemCitation1,Citation2, In Spain it is estimated that MS affects 50–70 of every 100,000 inhabitantsCitation3–6. About 85–90% of MS patients have the relapsing–remitting form of the disease (RRMS)Citation7,Citation8, in which patients have discrete motor, sensory, cerebellar or visual attacks that occur over 1–2 weeks and often disappear within 4–8 weeks, with or without treatmentCitation9. Some patients gain disability with each episode or exacerbation while remaining clinically stable between relapses. Others have many years of unrestricted activity punctuated by short-lived disturbances that resolve completelyCitation10.

MS is inhibiting to the individual, as it is chronic, disabling, and degenerative in its nature, containing a constant risk for re-occurrence and, hence, affecting a patient’s quality-of-life (QoL)Citation11. QoL was shown to decrease as patients suffering from relapse progress from mild to more severe disability levelsCitation12. MS also was shown to have significant costs for the Spanish NHS as well as for society which increases with disability progression, as published in several studiesCitation12,Citation13.

Currently there is no effective cure for MS. However, a treatment with disease modifying treatments (DMT) has been shown to slow disease progression and prevent new relapses in MSCitation8. An extensive literature review has listed existing studies on treatment with DMTCitation14. Glatiramer Acetate (GA) and Interferon beta-1a (IFN) have for many years been the most commonly prescribed therapies for RRMSCitation15. These treatments also have been subject to multiple health economic evaluations, in which they were compared directlyCitation16,Citation17. At current, several studies are ongoing for additional agents for the treatment of MS. Therefore, it seems likely that no single therapy will have the desired efficacy and long-term safety profiles. Combination therapy would, therefore, be the suggested solution. The CombiRx StudyCitation15,Citation18 is a 3-arm, randomized, double-blind trial which tests the combination of IFN and GA in RRMS. The objective was to determine whether the combined use of IFN 30 mg intramuscularly weekly and GA 20 mg subcutaneously daily was more efficacious for the treatment of RRMS than either agent in monotherapy alone. The main efficacy parameter was the reduction in annual relapse rate (ARR). After a 36-month period, it was observed that the combination with IFN + GA was not superior in reducing the ARR compared to one of the single agents alone. Based on the CombiRx study, the objective of this study was to assess cost-effectiveness of GA and IFN in monotherapy and in combination for Spanish patients with RRMS.

Methods

Model specifications

To assess the cost-effectiveness of the treatment with GA and IFN in monotherapy alone and IFN + GA in combination among patients diagnosed with RRMS in Spain, a Markov model was developed comparing three hypothetical cohorts, with 100,000 patients for each form of treatment. It was assumed that the patients in all three cohorts would take their medication over a time horizon of 10 years, with cycles with a length of 1 year.

The patients passed through five different health states, which included no relapses, suspected exacerbations, non-protocol defined exacerbations, protocol defined exacerbations, and information lost (). All patients started in the state with no relapses. The three included exacerbation states were based on the relapse definition of the types of exacerbations used in the CombiRx Study. In each 1-year cycle, a patient had a probability of having no relapses, having a suspected exacerbation (SE), a non-protocol defined exacerbation (NPDE), a protocol defined exacerbation (PDE) or fall in the category information lost (IL). Once they had experienced an exacerbation, a patient could not move back to the no relapse state. After a SE, a patient could stay in the same health state, re-experience the same kind of exacerbation, experience a NPDE or PDE or move to the category IL. Once they had experienced a NPDE or PDE, the patient could not go back to a SE or NPDE, respectively. Once a patient progressed to the category IL a patient would remain there for the rest of the simulation. All patients going out of the model went to the category Information lost and stayed there for the rest of the simulation. The category IL included all patients that left treatment at an early stage.

Transition probabilities

The transition probabilities for patients treated with GA and IFN in monotherapy alone and GA + IFN combined were obtained from the CombiRx studyCitation15, which analyzed the ARR for the three different treatment options over a 36-month period. These transitions, presented in , show the relative relapse risk and disease progression over time of patients treated with one of the three treatment options and the probability to experience a SE, a NPDE, a PDE or move to the category IL for the first year. The CombiRxCitation15 showed that the ARRs for cumulative years decrease with the stringency of exacerbation and with additional time on study. Therefore, the probabilities of experiencing an exacerbation independent of the type of exacerbation for the next 9 years of the simulation, shown to diminish over time, and the probability of patients who moved to the category information lost or left treatment increased. The effectiveness measure ARR obtained from the CombiRx studyCitation15 was determined for each treatment arm as the total number of relapses/total time on study at 36 months, using a Poisson regression model. GA was significantly better than IFN, reducing the risk of exacerbation by 31%, and the combination IFN + GA was significantly better than IFN, reducing the risk of exacerbation by 25% (p = 0.027 and 0.022, respectively). GA was more effective at reducing the ARR for SEs, NPDEs, and PDEs over the whole study period, than IFN and IFN + GA. The combination of IFN + GA tough was more effective in the reduction of the ARR for all three exacerbation types than IFN in monotherapy alone.

Table 1. Transition probabilities for the first year; GA and IFN in monotherapy and combined IFN + GA*.

Target patient groups

The model simulates a hypothetical cohort of 100,000 patients per treatment group, based on the population characteristics described in the CombiRx studyCitation15 which are described in an in-depth study by Lindsey et al.Citation19. Patients included were 1008 patients aged from 18–60 years, with an expanded disability status scale (EDSS) score of 0–5.5, and a diagnosis of RRMS by either the Poser et al.Citation20 or McDonald et al.Citation21 criteria. Patients had also experienced at least two exacerbations in the prior 3 years to the study; one exacerbation could be a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) change meeting the McDonald et al. MRI criteria for dissemination in time. Patients were on average 37.7 years old and had experienced an average duration of their illness of 4.3 years. None of the patients had formerly taken one of the two medications, GA, and/or IFN. All participants received at least one active medication, and all participants took the same number of injections. Patients received GA or IFN in monotherapy alone or in combination. Patients in the study were administered, respectively, IFN 30 mg intramuscularly once a week or GA 20 mg subcutaneously daily or a combination of IFN 30 mg intramuscularly once a week or GA 20 mg subcutaneously daily. In the study no safety issues were identified as resulting from the combination therapy. No unusual adverse events seen with the single agents were reported.

Costs

The costs included in this model consisted of the DMT treatment costs and the disease management costs for each health state. All costs and resources were obtained from published literature and updated to Euros 2013 where necessary. DMT pharmacological costs for GA and IFN monotherapy alone or their combination were based on their respective unit costs and presented in ex-factory prices and administration doses (). Administration doses for GA and IFN alone were taken from the CombiRx studyCitation15. Drug list prices were taken from the Spanish medicines databaseCitation22, and a 7.5% discount was applied to both drug prices, as indicated by law (Royal Decree 8/2010)Citation23. Based on the study of Sánchez-de la Rosa et al.Citation24, for IFN an administration cost was applied for each weekly administration of the drug ().

Table 2. Drug costs for GA 20 mg, IFN 30 mg, and GA + IFN, per unit and year.

The annual direct treatment costs were defined for each health state and their unit costs, and the number of resources are presented in . Costs for patients with no relapses only consisted of disease management costs, which included drug costs, medical visits to a specialist, and diagnostic tests. The number of resources and unit costs for disease management were obtained from the study of Sánchez-de la Rosa et al.Citation24. In case of an exacerbation, the costs for an exacerbation were added to the disease management costs. Costs for an exacerbation were dependent on the type of experienced exacerbation. Resources and unit costs for the three types of exacerbations were taken from the study by O’Brien et al.Citation25. The summarized total costs per health state are shown in . Once a patient moved to the category information lost, no costs were considered, as patients did not receive any treatment in this health state. A 3% discount rate was applied for costs and benefits, in accordance with the health economic guidelines of Pinto and SánchezCitation26.

Table 3. Annual resource utilization in units and unit costs in EUR 2013.

Table 4. Total annual cost in EUR 2013 per health state.

Analyses

The number of relapses avoided was included as the effectiveness measure to allow us to compare the value of the interventions across the different health states. The effectiveness and costs measured as the cost per number of relapses avoided in this study were established through the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) and are defined as:

In the comparison, ΔC is the difference in cost between both treatments and ΔE is the difference in effectiveness or relapses avoided between both treatments. In this study, two comparisons were made; GA vs IFN in monotherapy alone and GA alone vs the combination of IFN + GA.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to capture parameter uncertainty, its impact on model outcomes and results and to verify the robustness of the model. The variation in effects was expressed in terms of avoided relapses and costs, which were used as key model parameters. Statistical distributions were used for probabilities and costs to capture parameter uncertainty. Beta distributions were used for probabilities and Gamma distributions for costs. The results from three 1000 cohort iterations were presented as cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs).

Results

Base case

The base-case analysis consisted of three cohorts of patients with RRMS aged 18–60 years old treated with GA or IFN in monotherapy or IFN + GA in combination. In the base case the primary outcome was the cost per relapse avoided over a 10-year period. The total treatment cost per patient per year were the lowest for patients treated with GA in monotherapy, with €13,843 compared with €15,589 for IFN in monotherapy and €21,539 for the combination treatment with IFN + GA ().

Table 5. Total cost, incremental costs, relapse, relapse avoided and ICER.

The total number of relapses was estimated at 3.81, 4.18, and 4.08 for the treatment with GA and IFN in monotherapy, and IFN + GA in combination, respectively. The number of relapses was the lowest in the GA cohort, and less relapses occurred within the cohort treated with IFN + GA in combination than with INF in monotherapy only. GA was shown to reduce the ARR with −0.37 compared to IFN and with −0.27 compared to IFN + GA in combination (). The ICER showed that GA was the dominant treatment strategy, by being less costly and more effective, avoiding more annual relapses compared with IFN and IFN + GA ().

Sensitivity analysis

The probabilistic analysis showed stable figures for growing disparities in both costs and effects when introducing uncertainty around the input parameters. CEACs showed that treatment with IFN had a higher probability of being cost-effective than the treatment with GA for treatment costs less than €4000. For thresholds over €4000, GA was shown to have a higher probability to be cost-effective for all threshold values compared with IFN (). IFN + GA was shown to have a higher probability of being cost-effective than GA for values up to €28,000. GA had the highest probability for being cost-effective compared to IFN from €10,000, and from €28,000 compared to the combination treatment independent of the threshold the Spanish NHS is willing to pay for a treatment with DMT for RRMS ().

Discussion

This study investigated the cost-effectiveness of treatment of Spanish RRMS diagnosed patients over a 10-year time period using efficacy data on the ARR for exacerbations from the CombiRx StudyCitation15. Deterministic results in this study showed that the treatment with GA for RRMS was the dominant treatment strategy compared with IFN in monotherapy and IFN + GA in combination. The treatment with GA was shown to reduce the ARR and resulted in more relapses avoided than with the other two treatment options. Total treatment costs per patient associated with the treatment with GA were also the lowest compared to both other treatment strategies. The results for the comparison of GA and IFN in monotherapy are similar, as observed in the study of Castelli-Haley et al.Citation27 in which GA was shown to avoid more relapses and be less costly. In the study of Goldberg et al.Citation7, re-analyzed by Becker and DembekCitation28, the treatment with GA in monotherapy was also shown to be more effective in the reduction of ARR over a 2-year time period than with IFN intramuscularly, although not compared with subcutaneously administered IFN. Although other health economic evaluations have been undertaken which compare GA and IFN in monotherapy, comparison of results with these studies was difficult because of differences in methodology, design, and type of outcome measures comparedCitation16.

Our evaluation was based on 3-year efficacy data on ARR from the CombiRx studyCitation15. Recently new 7-year follow-up data from the extension of the CombiRx study has been published comparing also the three treatment options studied in our analysesCitation29–31. The results showed that GA in monotherapy continues to be superior in reducing the ARR compared with IFN in monotherapy and both agents combined, which is supportive for the cost-effectiveness results in this study.

The conclusions of this study need to be placed into the context of the assumptions made for this model. Important issues to consider are the multiple sources used for data inputs on ARR, costs of relapses, and disease progression. These issues have been addressed as much as possible by assuming conservative scenarios or by including a probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Disease management costs associated with DMT have been taken from the study of Sánchez-de la Rosa et al.Citation17 on Spanish patients which considered additional administration costs for IFN as it is administered in the hospital. This study also considered a weekly administration cost for IFN in monotherapy and in the combination treatment with IFN + GA over a 10-year time period. If no administration costs would be considered, the total costs of IFN (€10,051) would lower, but would still be more than with GA in monotherapy (€9420). Although the information has been published on the costs of an exacerbation in Spain by Gubieras et al.Citation11, there was no distinction made in the cost by severity of this relapse. Due to the lack of data on costs for the treatment of an exacerbation in Spain by severity level, costs for the treatment of exacerbations have been taken from the study of O’Brien et al.Citation25 conducted among US patients. It might be possible that small changes might exist in the treatment strategy for exacerbations in the Spanish setting which could affect the results in terms of costs.

In this study adverse effects have not been taken into account as a possible cause of additional treatment costs. The CombiRx studyCitation15 reported a normal occurrence of adverse events with the single agents and no safety issues identified as resulting from the combination therapy.

Adherence to DMT treatment for RRMS patients has been evaluated in two studies including Spanish patientsCitation32,Citation33 for a 2-year time period. The overall adherence rate reported was 85.4%. In our study we have not included the effect of adherence, although the dropout rate reported was low in each of three study arms, which adds to the reliability of the outcome. Still, adherence to the drugs has to be mentioned as a limitation for this study. Patients in this study based on the CombiRx studyCitation15 were administered, respectively, IFN 30 mg intramuscularly once a weekCitation34, or GA 20 mg subcutaneously dailyCitation35. If we would have taken into account the effects of adherence, as studied by Arroyo et al.Citation32 and Menzin et al.Citation36, to the treatment in a real life setting, where irregularities in adherence may be more probable than in the study setting, INF administered intramuscularly had a higher adherence than GA. These results are supported by a recent study from Brandes et al.Citation37 on adherence to DMT and its effect on cost-effectiveness which suggests that economic analyses of RRMS therapies should incorporate real-world adherence rates where available, rather than relying exclusively on trial-based efficacy estimates when considering the economic value of treatment alternatives. Therefore, adherence might have had an impact on the results, as shown in our study, although further investigation is necessary to interpret the total effect on the results in this study.

One uncertainty concerns the actual scale of benefit gained from these interventions in terms of delayed progression of disability. To include this uncertainty in the analysis, it would be necessary to obtain real data on the progress of people once they have stopped treatmentCitation38. This study has considerably lowered the uncertainty in estimation by calculating cost-effectiveness for a long-term treatment period of 10-years, eliminating the possibility of rebound effect for this time period. Longer-term studies including time after termination of treatment would allow us to include assumptions of delayed disease progression.

One uncertainty concerns the actual scale of benefit gained from these interventions in terms of delayed progression of disability. To include this uncertainty in the analysis, it would be necessary to obtain real data on the progress of people once they have stopped treatmentCitation37. This study has considerably lowered the uncertainty in estimation by calculating cost-effectiveness for long-term treatment of 10 years, eliminating the possibility of rebound effect for this time period. Longer-term studies including time after termination of treatment would allow including assumptions of delayed disease progressionCitation35.

Although the use of data of different sources implies the adaptation of several limitations which might affect the consistency of the results, the model was based on a limited number of assumptions. The model relied on evidence from a head-to-head comparison of GA and IFN in monotherapy alone and in combination, with data on ARR and disability progression evaluated in the same study. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis confirmed that the results would still hold despite the limitations of the data.

Conclusion

It may be concluded that GA in monotherapy alone is a cost-effective treatment option for the prevention of relapses compared with IFN in monotherapy and combined IFN + GA in patients diagnosed with RRMS. The treatment with GA in monotherapy was shown to result in a lower number of relapses and was less costly compared with the other two treatment options.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funding for the development of this manuscript was supplied by TEVA Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Declaration of financial/other interests

JD is employed by the University of Barcelona and has no relevant financial relationships to disclose. LK is an employee of BCN Health Economics & Outcomes Research S.L., Barcelona, Spain, an independent contract health economic organization that has received research funding from Teva Pharmaceutical. RS is employed by Teva Pharmaceutical and works at the Medical & HEOR Department. JME Peer Reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Dr Darbá’s and Mrs Kaskens’s contributions included designing the study, extracting data, conducting the analysis, and writing the draft and final manuscript. Dr Sanchez-de la Rosa’s contributions included designing the study, definition of study objective and analysis strategy, and reviewing the draft and final manuscript. Dr Darbá is guarantor of the manuscript.

References

- Weiner HL. The challenge of multiple sclerosis: how do we cure a chronic heterogeneous disease? Ann Neurol 2009;65:239-48

- IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. I. Clinical results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 1993;43:655-61

- Casquero P, Villoslada P, Montalban X, et al. Frequency of multiple sclerosis in Menorca, Balearic Islands, Spain. Neuroepidemiology 2001;20:129-33

- Modrego PJ, Pina MA. Trends in prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis in Bajo Arago´ n, Spain. J Neurol Sci 2003;216:89-93

- Aladro Y, Alemany MJ, Perez-Vieitez MC, et al. Prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis in Las Palmas, Canary Islands, Spain. Neuroepidemiology 2005;24:70-5

- Ares B, Prieto JM, Lema M, et al. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Santiago de Compostela (Galicia, Spain). Mult Scler 2007;13:262-4

- Goldberg LD, Edwards NC, Fincher C, et al. Comparing the cost-effectiveness of disease-modifying drugs for the first-line treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Manage Care Pharm 2009;15:543-55

- García Merino A, Fernández O, Montalbán X, et al. [Spanish Neurology Society consensus document on the use of drugs in multiple sclerosis: escalating therapy]. Neurologia 2010;25:378-90

- Weiner HL, Hohol MJ, Khoury SJ, et al. Therapy for multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin 1995;13:173-96

- Goodkin DE. Interferon beta therapy for multiple sclerosis. Lancet 1998;352:1486-7

- Gubieras L, Casado V, Romero-Pinel L, et al. Cost of the relapse of multiple sclerosis in Spain. Value Health 2011;14:233-510

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, et al. Costs and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in Spain. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:65-74

- Casado V, Martinez-Yelamos S, Martinez-Yelamos A, et al. The costs of a multiple sclerosis relapse in Catalonia (Spain)]. Neurología 2006;21:341-7

- Clegg A, Bryant J, Milne R. Disease-modifying drugs for multiple sclerosis: a rapid and systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2000;4:1-101

- Lublin FD, Stacey S, Cofield SS, et al; Wolinsky JS, for the CombiRx Investigators; Randomized study combining interferon and glatiramer acetate in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2013;73:1-14

- Yamamoto D, Campbell JD. Cost-effectiveness of multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapies: a systematic review of the literature. Autoimmune Dis Hindawi Publishing Corporation 2012;2012:1-13

- Sánchez-de la Rosa R, Sabater E, Casado MA, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of disease modifiying drugs (interferons and glatiramer acetate) as first line treatments in remitting-relapsing multiple sclerosis patients. J Med Econ 2012;15:424-33

- Lublin FD, Cofield SS, Gustafson T, et al; Cutter GR for the The CombiRx Investigators Investigators. Assessment of relapse activity in the CombiRx Randomised Clinical Trial. 28th Congress of the European Committee for treatment and research in Multiple Sclerosis, 10-13 October 2012, Lyon, France. http://registration.akm.ch/einsicht.php?XNABSTRACT_ID=157254&XNSPRACHE_ID=2&XNKONGRESS_ID=171&XNMASKEN_ID=900. Last accessed 25 October 2013

- Lindsey J, Scott T, Lynch S, et al; the CombiRx Investigators Group. The CombiRx trial of combined therapy with interferon and glatiramer cetate in relapsing remitting MS: design and baseline characteristics. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2012;1:81-6

- Poser CM, Paty DW, Scheinberg L, et al. New diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines for research protocols. Ann Neurol 1983;13:227-31

- McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2001;50:121-7

- Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos. BOT plus web. 2013. https://botplusweb.portalfarma.com/. Last accessed 25 October 2013

- Real Decreto-Ley 8/2010, de 20 de mayo, por el que se adoptan medidas extraordinarias para la reducción del déficit publico. Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), Madrid, 24 May 2010, no 126. Sec. I, p. 45070-128 http://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2010/05/24/pdfs/BOE-A-2010-8228.pdf. Last accessed 25 October 2013

- Sánchez-De la Rosa R, Sabater E, Casado MA. Análisis del impacto presupuestario del tratamiento en primera línea de la esclerosis múltiple remitente recurrente en España. Rev Neurol 2011;53:129-38

- O'Brien JA, Ward AJ, Patrick AR, et al. Cost of managing an episode of relapse in multiple sclerosis in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res 2003;3:17

- Pinto JL, Sanchez F. Métodos para la evaluación económica de nuevas prestaciones. Editado por: Centre de Recerca en Economía i Salut – Cres y Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, España. http://www.msc.es. Accessed April 10, 2013

- Castelli-Haley J, Oleen-Burkey MA, Lage MJ, et al. Glatiramer acetate and interferon beta-1b: a study of outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther 2009;26:552-62

- Becker RV, Dembek C. Effects of cohort selection on the results of cost-effectiveness analysis of disease-modifying drugs for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Manage Care Pharm 2011;17:377-81

- Lublin F, Cofield S, Cutter G, et al. Relapse activity in the CombiRx Trial: blinded, 7-year extension results. Neurology 2013;80:(Meeting Abstracts) Poster number S01-002

- Lublin F, Cofield S, Cutter G, et al. EDSS changes in CombiRx: blinded, 7-year extension results for progression and improvement. Neurology 2013;80(Meeting Abstracts 1): Poster number Poster number P04.121

- Wolinsky J, Salter A, Narayana P, et al. MRI Outcomes in CombiRx: blinded, 7-year extension results. Neurology 2013;80(Meeting Abstracts 1): Poster number S01.003

- Arroyo E, Grau C, Ramo-Tello C, et al; GAP Study Group. Adherence to disease-modifying therapies in Spanish patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: two-year interim results of the global adherence project. Eur Neurol 2011;65:59-67

- Arroyo E, Grau C, Ramo C, et al; por el grupo espanol del estudio GAP. [Global adherence project to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: 2-year interim results]. Neurologia 2010;25:435-42

- European Medicines Agency. Summary of product characteristics Avonex. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000102/WC500029425.pdf. Last accessed 25 October 2013

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Ficha Técnica Copaxone. http://www.aemps.gob.es/cima/especialidad.do?metodo=verPresentaciones&codigo=65983. Last accessed 25 October 2013

- Menzin J, Caon C, Nichols C, et al. Narrative review of the literature on adherence to disease-modifying therapies among patients with multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Pharm 2013;19(1 Suppl):S24-40

- Brandes DW, Raimundo K, Agashivala N, et al. Implications of real-world adherence on cost-effectiveness analysis in multiple sclerosis. J Med Econ 2013;16:547-51

- Chilcott J, McCabe C, Tappenden P, et al; Claxton K on behalf of the Cost Effectiveness of Multiple Sclerosis Therapies Study Group. Modelling the cost effectiveness of interferon beta and glatiramer acetate in the management of multiple sclerosis. BMJ 2003;326:522