Abstract

Objectives:

A recent phase III trial showed that patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) whose tumors harbor specific EGFR mutations significantly benefit from first-line treatment with erlotinib compared to chemotherapy. This study sought to estimate the budget impact if coverage for EGFR testing and erlotinib as first-line therapy were provided in a hypothetical 500,000-member managed care plan.

Methods:

The budget impact model was developed from a US health plan perspective to evaluate administration of the EGFR test and treatment with erlotinib for EGFR-positive patients, compared to non-targeted treatment with chemotherapy. The eligible patient population was estimated from age-stratified SEER incidence data. Clinical data were derived from key randomized controlled trials. Costs related to drug, administration, and adverse events were included. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess uncertainty.

Results:

In a plan of 500,000 members, it was estimated there would be 91 newly diagnosed advanced NSCLC patients annually; 11 are expected to be EGFR-positive. Based on the testing and treatment assumptions, it was estimated that 3 patients in Scenario 1 and 6 patients in Scenario 2 receive erlotinib. Overall health plan expenditures would increase by $0.013 per member per month (PMPM). This increase is largely attributable to erlotinib drug costs, in part due to lengthened progression-free survival and treatment periods experienced in erlotinib-treated patients. EGFR testing contributes slightly, whereas adverse event costs mitigate the budget impact. The budget impact did not exceed $0.019 PMPM in sensitivity analyses.

Conclusions:

Coverage for targeted first-line erlotinib therapy in NSCLC likely results in a small budget impact for US health plans. The estimated impact may vary by plan, or if second-line or maintenance therapy, dose changes/interruptions, or impact on patients’ quality-of-life were included.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer in both men and women and the leading cause of all cancer deaths in the US, accounting for 27% of all cancer deathsCitation1. An estimated 224,210 new cases will be diagnosed and 159,260 persons will die from lung cancer in the US in 2014. The 5-year survival after diagnosis remains very poor at only 15.9%Citation2. Lung cancer is divided into two primary types, small cell and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the latter of which accounts for ∼85–90% of all lung cancersCitation1.

Erlotinib (Tarceva, Genetech Inc., San Francisco, CA) is an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor that was approved for second- or third-line therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC in the US in 2004, and for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC whose disease has not progressed after four cycles of platinum-based first-line chemotherapy by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—referred to as maintenance therapy—in 2010. Most recently, in May 2013, erlotinib’s indication was extended to include first-line treatment of patients with metastatic NSCLC whose tumors harbor EGFR exon 19 deletions or exon 21 (L858R) substitution mutations as detected by an FDA-approved test. The latest approval was supported by data from a recent phase III clinical trial, EURTAC, which demonstrated that first-line treatment with erlotinib significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared with standard chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC patients whose tumors harbored EGFR mutations.

As treatment with erlotinib introduces some complexity in the treatment patterns for NSCLC due to the introduction of mutation testing as a driver of treatment selection, we developed a budget impact model to better understand the potential impact of adding erlotinib to a health plan formulary for first-line treatment of EGFR-positive patients. The model evaluated the cost implications for testing patients with advanced NSCLC and treating those who are EGFR-positive in a hypothetical health plan of 500,000 members.

Patients and methods

Model overview

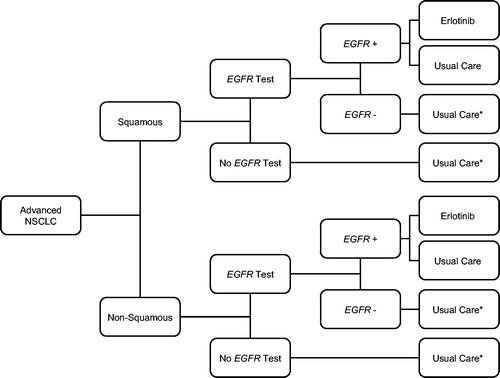

This budget impact model compared the annual cost of testing all first-line advanced (stage IIIB or IV) NSCLC patients for EGFR mutations, and treating patients who are EGFR-positive with erlotinib vs usual care. The model included testing costs, but not treatment-related costs for EGFR-negative patients, as the costs of treating EGFR-negative patients would be equivalent in both scenarios. illustrates the model schematic.

Figure 1. Model schematic. *EGFR negative patients are not followed in the model as their outcomes are not differential between scenarios.

In Scenario 1 (current scenario), we estimated that 50% of patients are currently being tested for the EGFR mutation based on a 2010 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) survey of cancer cliniciansCitation3. The NCCN survey found that 21–41% of clinicians often test patients for the EGFR mutation, 23–26% sometimes test patients for the EGFR mutation, and the remaining either never or seldom test for the EGFR mutation at the time of presentation (ranges dependent on the stage of cancer). Based on this survey, we selected 50% as a plausible and potentially conservative estimate for patients receiving EGFR testing, as the rate of EGFR testing is likely to have increased since 2010. We assumed that 90% of patients who test EGFR-positive receive erlotinib; the remaining 10%, as well as those who are not tested but have underlying EGFR-positive status, receive usual care. In Scenario 2 (future scenario), we calculated the expected annual cost of testing all patients for EGFR mutations and treating 90% of EGFR-positive patients with erlotinib; the remaining 10% receive usual care. We assumed that 10% of EGFR-positive patients will continue to receive usual care because, while erlotinib is recommended for use as first-line therapy in the NCCN guidelines, some patients may continue to receive usual care based on physician or patient preferencesCitation2. Treatment-related costs included drug costs, administration costs, and costs of treatment of drug-related adverse events. All inputs were varied in the sensitivity analysis.

Patient population

The budget impact model considered a health plan with 500,000 enrollees. Population-based incidence data were combined with US Census data to estimate the expected annual number of patients with advanced NSCLCCitation4. Incidence rates for advanced NSCLC were estimated from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program for the years 2000–2010Citation5. The model assumes the population is in a steady state with respect to the incidence of new cases.

We assumed that, in the base case health plan, the age and gender distribution are the same as in the US population, with the exception that only a proportion of people in the 65 years and above age category participate in managed care plans. Hence, to ensure the estimated budget impact is relevant to decision-makers in US commercial managed care plans, US Census data were adjusted to reflect the fact that ∼25% of patients 65 years and above participate in managed care plans (i.e., Medicare Advantage plans) by removing 75% of the population estimate for the 65 years and above age categoryCitation6.

The proportion of patients within each age and gender group in the health plan was applied to the SEER age-specific incidence rates per 100,000 persons to estimate the annual incidence of advanced NSCLC in the managed care population (see ). To calculate the final number of erlotinib eligible patients, the estimated number of patients in each age and sex stratified group was multiplied by the proportion of tumors expected to be squamous (22%) vs non-squamous (78%) histology, and the prevalence of EGFR mutations in each histology type (3% and 15%, respectively). The prevalence estimates for EGFR mutations in squamous and non-squamous patients were based on published studiesCitation2,Citation7,Citation8.

Table 1. Advanced NSCLC patient population estimation.

Treatments

We estimated that 55% of incident cases of advanced NSCLC receive treatment for this cancer based on a study by Ritzwoller et al.Citation9. Ritzwoller et al. found that ∼55% of patients newly diagnosed with advanced NSCLC received treatment within 120 days of diagnosis, with some variation based on patient characteristics.

The treatment regimens considered in the model for patients with squamous histology NSCLC included: (1) erlotinib and (2) paclitaxel + carboplatin. The treatment regimens considered in the model for patients with non-squamous histology NSCLC included: (1) erlotinib, (2) paclitaxel + carboplatin, (3) bevacizumab + paclitaxel + carboplatin, (4) pemetrexed + carboplatin, and (5) bevacizumab + pemetrexed + carboplatin.

Drug and administration costs

The drug and administration costs for each regimen were factored into the model. The wholesale acquisition costs (WAC) were used for the cost of the drugs, which were derived from the 2013 Analy$ource databaseCitation10. The drug cost per patient per administration was calculated using the average patient baseline characteristics, administration instructions, and median treatment durations from the relevant clinical trial publications and prescribing information (PI) sheetsCitation11–17. Drug costs were calculated under the assumption that patients will use drugs in accordance with the product label. Drug costs accounted for wastage; however, the cost impact of dose reductions and dose delays was not addressed. Further, it was expected that treatment costs would be incurred within 12 months of diagnosis.

Intravenous infusion costs for the therapies were determined using rates from the 2013 Medicare reimbursement rate. The first hour of infusion was $143.24 (CPT code: 96413), and each additional hour of infusion was $30.62 (CPT code: 96415)Citation18. Testing costs for the EGFR mutations were based on the 2013 Palmetto GBA MoPath Fee Schedule for the EGFR test ($225.00)Citation19.

Treatment costs and inputs are summarized in .

Table 2. Treatment costs and market share by therapy.

Market share distribution

In Scenario 1 (50% EGFR testing rate), erlotinib was assumed to capture 90% of the market share in those who are tested for EGFR mutations, test positive, and receive treatment. Those patients who are not tested but have an underlying mutation receive usual care. The market share of each chemotherapy regimen (paclitaxel + carboplatin, bevacizumab + paclitaxel + carboplatin, pemetrexed + carboplatin, bevacizumab + pemetrexed + carboplatin) was based on Genentech market share estimates (Genentech. Data on file; Q4 2012 NSCLC Tracker). The likelihood that each treatment will be used in the base case analysis is shown in .

In Scenario 2 (100% EGFR testing rate), it was also assumed that 90% of EGFR-positive patients will be treated with erlotinib; i.e., erlotinib captures 90% of market share for both squamous and non-squamous patients. Approximately 3% of squamous and 15% of non-squamous tumors were estimated to test positive for EGFR mutations in both scenariosCitation2,Citation7,Citation8.

It is worth mentioning that we did not incorporate the sensitivity or specificity of the EGFR test in our calculations of the size of the EGFR-positive patient population or in the market share estimates for each treatment. As it is the result of the EGFR test that drives treatment selection, and not necessarily the patient’s true underlying EGFR mutational status, we felt omitting the sensitivity and specificity parameters from the model was a better representation of how treatment decisions would be made in the real world. Further, clinical studies of the efficacy of treatments targeted to EGFR-positive patients, including erlotinib, are also done with treatment selection based on imperfect test results; therefore, efficacy estimates should reflect the potential misallocation of patients to targeted or non-targeted therapies due to imperfect sensitivity or specificity of the EGFR test.

Adverse events and costs

The cumulative proportion of patients with each adverse event was used to estimate the expected cost of adverse events for an average patient. Serious or grades 3 and 4 adverse events occurring in greater than 5.0% of patients were considered and data were derived from the prescribing information and/or pivotal studies for each treatment regimenCitation12–15,Citation17,Citation20–22. The absolute event rates were applied. When an adverse event was included for one treatment, the absolute event rates for that adverse event were reported for all other treatments in the model.

The costs of managing each adverse event were assumed to be the same between the current and future scenarios. All costs were based on 2013 Medicare reimbursement rates and the WAC prices for each drugCitation10,Citation18,Citation23. Rates of adverse events per treatment were multiplied by the costs and resource use for each specific adverse event to calculate total expected costs of adverse events by treatment. Resource use for each adverse event was assumed to be independent.

Analysis

The budget impact analysis was performed from the perspective of a private health insurer in the US over a 1-year time periodCitation24. Model outcomes are reported for total and incremental costs by scenario and as a per member per month (PMPM) cost comparing Scenario 2 to Scenario 1.

We conducted one-way sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of parameter uncertainty. To do so, we varied key parameters one-by-one, predominantly using uncertainty ranges of ±10–20%. We used an uncertainty range of 10% for parameters where data were leveraged from clinical trials or other reliable sources; this included estimates for plan demographics, NSCLC incidence estimates, and treatment patterns, durations, effects, and costs. We varied parameters with greater uncertainty by 20%, including estimates for adverse events rates and costs of adverse events. Notably, the estimate for the rate of EGFR testing in Scenario 1 was varied by ±50%, as testing rates may vary widely across plans.

Results

In a hypothetical health plan of 500,000 members, we estimated that there would be 91 newly diagnosed advanced NSCLC patients each year. Of these, 11 patients are expected to be EGFR-positive, and therefore eligible for first-line treatment with erlotinib (see ). Based on the testing and treatment assumptions described, we estimated that 3 patients are treated with erlotinib in Scenario 1 and 6 patients are treated with erlotinib in Scenario 2 as first-line therapy.

details the treatment cost calculations for each treatment regimen. Treatment with erlotinib is estimated to cost $63,414 per patient. Treatment with the chemotherapy regimens ranges from $2,803–$89,229. Detailed results are summarized in . EGFR test costs double from Scenario 1 to Scenario 2 due to the assumed change in testing rate among the 91 cases of newly diagnosed advanced NSCLC. The estimated costs of treatment and adverse events are presented by treatment, and then summarized across treatments at the bottom of the table. Treatment costs and adverse event costs reflect the varying costs of each treatment regimen and the number of patients receiving each regimen, calculated based on the number of expected patients with advanced squamous and non-squamous NSCLC () and the market share estimates for each regimen (). The expected costs of treating adverse events associated with erlotinib increases from $4995 in Scenario 1 to $9990 in Scenario 2, based on the higher number of patients receiving erlotinib in Scenario 2. Similarly, we see decreasing estimates of adverse event costs for other treatment regimens, as fewer patients receive these alternative treatments in Scenario 2.

Table 3. Detailed results: squamous and non-squamous histologies.

The changes in total costs per member per month were calculated by dividing the change in total costs by the total number of plan members (500,000) and number of months (12). The overall health plan expenditures increased by $0.013 PMPM. This increase is largely attributable to increased drug costs for patients receiving erlotinib who experience longer progression-free survival and treatment duration. EGFR test costs also contribute slightly to the increased expenditures, whereas adverse event costs are slightly lower: EGFR testing costs contribute $0.002 to the PMPM change, while there is an offsetting decrease in adverse event treatment cost of $0.002 ().

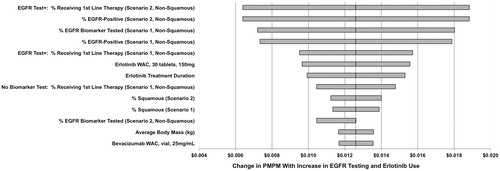

Sensitivity analysis

The effect of varying key parameters on PMPM is described in . The most influential model parameters are the percentage of patients receiving first-line therapy, the percentage of patients that are EGFR-positive, the percentage of patients tested for EGFR mutations, drug cost, and treatment duration. In all scenarios, the increase in PMPM is less than $0.019.

Discussion

The objective of this analysis was to determine the budget impact of increasing EGFR testing rates and the addition of erlotinib as a first-line therapy for EGFR-positive patients. In a hypothetical plan of 500,000 members, the expected impact of increasing EGFR testing rates from 50% to 100% among advanced NSCLC patients and treating EGFR-positive patients with erlotinib as first-line therapy is $0.013 PMPM. The total increase in annual costs is expected to be $75,685. The increased costs are largely attributable to increased drug costs for patients receiving erlotinib, who experience longer progression-free survival and treatment duration.

The modest budget impact associated with increased EGFR testing and the addition of erlotinib as a first-line therapy for EGFR-positive patients highlights that the higher treatment costs associated with erlotinib are mitigated by its targeted use. Testing for biomarker prevalence ensures that erlotinib is used only in patients who will benefit most from treatment with erlotinib. Further, the implications of increasing testing rates should be considered against the larger backdrop of the potential use of multiplex and next-generation sequencing tests going forward; when multiple tests can be bundled, this reduces patient and physician burden, can reduce the incremental costs of testing, and may improve efficiency in the diagnosis of disease and selection of therapy.

Further, the model structure and assumptions were such that the budget impact calculation is likely conservative in nature—i.e., the calculated budget impact may be higher than in actual practice. For instance, the budget impact model includes only first-line treatment. Including second-line treatment likely would lead to greater costs in Scenario 1, as erlotinib is currently used in a substantial proportion of patients as second-line therapy. Thus, the actual budget impact in practice for health plans that currently have erlotinib second-line therapy on formulary may be lower. Further, in Scenario 1, it is assumed 50% of patients receive EGFR testing based on a 2010 NCCN survey of 509 cancer clinicians that found 65% of clinicians sometimes or often order EGFR testing for patients with metastatic NSCLCCitation3; EGFR testing rates have likely risen since this time. The assumption that 100% of patients will receive biomarker testing in Scenario 2 is also a conservative approach, as uniform testing is unlikely. Overall, the difference in EGFR testing rates between the current and future scenarios is likely to be smaller than assumed in the base case analysis, leading to a smaller budget impact in reality.

There are several limitations to the model developed. The model does not account for changes in drug dosages or treatment interruptions, which may have a significant impact on treatment costs. Addition of these intricacies to the model could lead to a higher or lower estimated budget impact, depending on the rates of dosage changes or interruptions. The model also assumes that health plans will incur the costs of treatment for the full duration of treatment, regardless of whether patients fill all prescriptions or incur any copayment fees. This assumption likely results in an elevated PMPM calculation in our model, as patient behaviors and cost-sharing mechanisms typically translate to fewer prescription fills and a reduced financial burden for the health plan. The model does not consider maintenance treatments or treatments related to NSCLC recurrence. As previously described, inclusion of second-line and maintenance therapies would likely reduce the estimated budget impact, since many patients currently receive erlotinib for these purposes. The findings may not be generalizable to all payers; payers with a greater proportion of older members are likely to see more NSCLC patients and a potentially greater budget impact. Finally, the budget impact model does not assess the impact of erlotinib beyond that on costs; impact on the patients’ health-related quality-of-life may be significant for this life-extending oral therapy.

Conclusions

Targeted treatment with erlotinib as first-line therapy for EGFR positive patients in advanced NSCLC likely leads to a small increase in PMPM cost. Although treated patients have a significant increase in progression-free survival and concomitant treatment duration, the targeted population is a small proportion of eligible patients, leading to a modest budget impact. The cost to perform EGFR testing has a minimal impact on the PMPM cost.

Notice of Correction

The version of this article published online ahead of print on 12 May 2014 contained an error in the abstract and in the results section on page 543. In the abstract, the sentence “Based on the testing and treatment assumptions, it was estimated that five patients in Scenario 1 and 10 patients in Scenario 2 receive erlotinib” should have read “Based on the testing and treatment assumptions, it was estimated that 3 patients in Scenario 1 and 6 patients in Scenario 2 receive erlotinib”. On page 543, the sentence “Based on the testing and treatment assumptions described, we estimated that five patients are treated with erlotinib in Scenario 1 and 10 patients are treated with erlotinib in Scenario 2 as first-line therapy” should have read “Based on the testing and treatment assumptions described, we estimated that 3 patients are treated with erlotinib in Scenario 1 and 6 patients are treated with erlotinib in Scenario 2 as first-line therapy.” The errors have been corrected for this version.

Since the notice of correction was published on 09 July 2014 a further error has been found on page 541. The sentence “Grades 3 and 4 adverse events occurring in greater than 5.0% of patients were considered and data were derived from the prescribing information and/or pivotal studies for each treatment regime” should have read “Serious or grades 3 and 4 adverse events occurring in greater than 5.0% of patients were considered and data were derived from the prescribing information and/or pivotal study publication for each treatment regimen.” This error has been corrected for this version.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Genentech, Inc. The authors had full control of the design, analysis, interpretation, and reporting of the study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

P. Bajaj has served as a consultant for Genentech and the National Pharmaceutical Council. J. Carlson has served as a consultant for Genentech and Life Technologies Inc. D. Veenstra has served as a consultant for Genentech, Abbott Diagnostics, and the National Pharmaceutical Council. H. Goertz is an employee of Genentech Inc. JME Peer Reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

- What are the key statistics about lung cancer? American Cancer Society Web Site. http://www.cancer.org. Updated February 10, 2014. Accessed February 22, 2014.

- National comprehensive cancer network. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 2.2013. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013;11(6):645-53.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Trends Results July 2010: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Fort Washington, PA. NCCN; 2010.

- United States Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population by sex and five-year age groups for the United States, April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2013.

- SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2012 Sub (2000–2010) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment>. National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch; 2013. Accessed April 2013

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Sources of supplemental coverage among Medicare Beneficiaries, 2009. Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2009.

- Sequist LV, Neal JW. Personalized, genotype-directed therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. UpToDate Website. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/personalized-genotype-directed-therapy-for-advanced-non-small-cell-lung-cancer. Updated June 12, 2013. Accessed June 21, 2013.

- Hirsch FR, Bunn PA Jr. EGFR testing in lung cancer is ready for prime time. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:432-3

- Ritzwoller DP, Carroll NM, Delate T, et al. Patterns and predictors of first-line chemotherapy use among adults with advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the cancer research network. Lung Cancer 2012;78:245-52

- Analysource. Analysource online: The online resource for drug pricing and deal information. 2013. www.analysource.com

- Genentech, Inc. Clinical Study Report E4599. A randomized phase II/III trial of paclitaxel plus carbolplatin with or without bevacizumab in patients with advanced nonsquamous NSCLC. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc.; 2006.

- Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2542-50

- F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd. Clinical Study Report - Research Report 1050832. Basel, Switzerland: F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd.; 2012

- Socinski MA, Raju RN, Stinchcombe T, et al. Randomized, phase II trial of pemetrexed and carboplatin with or without enzastaurin versus docetaxel and carboplatin as first-line treatment of patients with stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1963-9

- Patel JD, Hensing TA, Rademaker A, et al. Phase II study of pemetrexed and carboplatin plus bevacizumab with maintenance pemetrexed and bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3284-9

- Astellas Pharma US, Inc., and Genentech, Inc. Tarceva® Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2013.

- Genentech, Inc. Avastin® Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Diagnosis related group codes.

- MoPath Fee Schedule.Palmetto GBA Web Site.http://palmettogba.com/medicare. Updated April 1, 2013. Accessed April 6, 2013

- Pfizer Labs. Xalkori® Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2013.

- Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1693-703

- Sandler A, Yi J, Dahlberg S, et al. Treatment outcomes by tumor histology in Eastern Cooperative Group Study E4599 of bevacizumab with paclitaxel/carboplatin for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1416-23

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Physician fee schedule (CY 2013). Baltimore, MD: CMS; 2013

- Sullivan SD, Mauskopf JA, Augustovski F, et al. Budget impact analysis-principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 Budget Impact Analysis Good Practice II Task Force. Value Health: J Int Soc Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2014;17:5-14

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Vol. IX. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2007.