Abstract

Background:

Defensive medicine represents one cause of economic losses in healthcare. Studies that measured its cost have produced conflicting results.

Objective:

To directly measure the proportion of primary care costs attributable to defensive medicine.

Research design and methods:

Six-week prospective study of primary care physicians from four outpatient practices. On 3 distinct days, participants were asked to rate each order placed the day before on the extent to which it represented defensive medicine, using a 5-point scale from 0 (not at all defensive) to 4 (entirely defensive).

Main outcome measures:

This study calculated the order defensiveness score for each order (the defensiveness/4) and the physician defensive score (the mean of all orders defensiveness scores). Each order was assigned a weighted cost by multiplying the total cost of that order (based on Medicare reimbursement rates) by the order defensiveness score. The proportion of total cost attributable to defensive medicine was calculated by dividing the weighted cost of defensive orders by the total cost of all orders.

Results:

Of 50 eligible physicians, 23 agreed to participate; 21 returned the surveys and rated 1234 individual orders on 347 patients. Physicians wrote an average of 3.6 ± 1.0 orders/visit with an associated total cost of $72.60 ± 18.5 per order. Across physicians, the median physician defensive score was 0.018 (IQR = [0.008, 0.049]) and the proportion of costs attributable to defensive medicine was 3.1% (IQR = [0.5%, 7.2%]). Physicians with defensive scores above vs below the median had a similar number of orders and total costs per visit. Physicians were more likely to place defensive orders if trained in community hospitals vs academic centers (OR = 4.29; 95% CI = 1.55–11.86; p = 0.01).

Conclusions:

This study describes a new method to directly quantify the cost of defensive medicine. Defensive medicine appears to have minimal impact on primary care costs.

Keywords::

Introduction

Defensive medicine, defined as ‘the practice of ordering medical tests, procedures, or consultations of doubtful clinical value in order to protect the prescribing physician from malpractice suits’Citation1 is believed to be a significant factor driving the overall cost of the US healthcare system, which already accounts for 15.2% of the annual GDPCitation2. Surveys by Gallup and Jackson Healthcare estimated that up to 92% of US physicians practice defensive medicine and that costs associated with defensive medicine could represent $650–$850 billion per year (26–34% of the annual healthcare costs)Citation3.

However, the true medical cost associated with defensive medicine is not known and has only been indirectly estimated. Studies assessing medical decisions as well as patient outcomes in states with and without medical tort reforms have produced conflicting results. Kessler and McClellanCitation4 examined hospitalized Medicare patients and found that, compared to states without tort reform, those with tort reform experienced a significant decline in hospital spending for myocardial infarction and ischemic heart disease. Baicker et al.Citation5 found that higher malpractice awards and premiums are associated with higher Medicare spending, especially for imaging services, which may be driven by physicians’ fear of malpractice litigation. In contrast, othersCitation6,Citation7 have found that tort reforms have little impact on medical decisions and do not produce significant cost savings. Survey studies employing self-reporting or hypothetical scenarios have also produced conflicting resultsCitation8–10. All attest to the difficulty of assessing the direct cost of defensive medicine.

The primary objective of this study was to quantify through direct measurement the proportion of total costs attributable to defensive medicine in the primary care setting. The secondary objective was to examine physician and patient factors associated with the practice of defensive medicine.

Patients and methods

Study setting and participants

We enrolled primary care physicians (internal medicine and family medicine) from four outpatient practices within one healthcare system (Cleveland Clinic Health System) in Northeast Ohio. All physicians in these locations received an email explaining the study and an invitation to participate. Physicians who agreed to participate were contacted by the study co-ordinator, who obtained written consent. No incentives were offered for participating in the study. In addition, all physicians are employed on a fixed-salary model and, therefore, there is no direct financial benefit to the physicians from ordering more tests. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cleveland Clinic.

Data collection

Data were collected in August and September 2013. Each participant provided demographic information and completed an attitude survey with information on whether they had been sued, knew anyone who had been sued, and how much they feared being sued (Supplement 1). Then for each physician we randomly selected three separate workdays at least 1 week apart (that physicians were unaware of), and used the electronic health records to generate a list of all orders (except medications) placed by the physician on each chosen day. The following day, through the Cleveland Clinic intranet, physicians were asked to rate each order on the extent to which it represented defensive medicine, using a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all defensive) to 4 (entirely defensive). Medication orders were excluded because the majority of patients who physicians followed in their practices were established patients requiring medication refills for chronic conditions and were unlikely to be defensive in nature. Rating each medication order seemed unduly burdensome. For each patient we also recorded age, sex, health insurance, and the diagnosis associated with each order. For analysis purposes, orders were grouped in seven categories: vaccines, equipment (e.g., wrist splint, compression stockings, and continuous positive airway pressure device), laboratory (e.g., comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count), imaging (e.g., radiograph, computed tomography), diagnostic cardiology (e.g., electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, Holter monitor), procedures (e.g., colonoscopy), and consultations.

Data analysis

The primary objective of this study was to quantify the proportion of total costs attributable to defensive medicine in the primary care setting. In order to determine this proportion, we converted the Likert-like scaled defensiveness score for each order (range = 0–4) into a proportion by dividing it by 4. We then determined the attributable cost of defensive orders by multiplying each order’s defensive proportion by the cost of that order (e.g. an order rated 2 would have a proportion of 2/4, so one-half of that order’s cost would be considered to be defensive). Costs were assigned using the published 2013 Medicare fee schedules. The costs for laboratory orders were identified using the 2013 clinical laboratory fee scheduleCitation11 and included the 60% national limitation amount for each test. The costs for durable medical equipment were identified using the 2013 durable medical equipment, prosthetics, orthotics, and supplies fee scheduleCitation12 and included the ceiling amount for each item. The costs for vaccines, imaging, diagnostic cardiology, procedures, and consultation orders were identified using the 2013 physician fee scheduleCitation13 and included all applicable modifiers (professional component, technical component, global service, or physicians professional service where the professional or technical concept did not apply). We then divided the cost attributable to defensive medicine by the total cost of all orders to estimate the proportion of total costs due to defensive practices. For each physician, we estimated a defensiveness score, defined as the mean of the defensiveness proportions for all orders placed by that physician. Physicians with defensiveness scores above the median were considered to be highly defensive, and those with scores below the median were considered less defensive.

For the primary objective, the outcomes were summarized as means and standard deviations or medians and inter-quartile ranges (IQR) as appropriate. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare each outcome between highly defensive and less defensive physicians.

The secondary objective of the study was to assess physician and patient factors associated with the practice of defensive medicine. Predictor variables included physician demographics, such as gender, number of years in practice, medical school (US vs international graduates), residency training (academic vs community hospital), experience (history of being sued, knowing somebody that has been sued), attitude (fear of being sued, belief that practicing defensively protects against being sued), as well as patients characteristics, such as age, sex, type of insurance (private, Medicare, Medicaid, or none), and order category. Physician and patient characteristics were examined using the random-effect logistic models. Each order was dichotomized as defensive (>0 on the scale) or not. The models contain each characteristic as a fixed predictor and a random intercept representing the correlations of repeated orders within each physician. Statistical significance was established with a two-sided p-value <0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC) and R (cran.r-project.org).

Results

Of 50 physicians who received invitations, 23 agreed to participate, 22 completed demographic surveys, 21 completed at least one order survey and 20 completed all four surveys, rating 1234 individual orders on 347 unique patients. There were an average of 3.6 ± 1.0 orders per patient per visit, with an associated cost of $72.6 ± 18.5 per order. Characteristics of the participants appear in . The demographic characteristics, including gender, years in practice, place of medical school, and type of residency, were similar between the physicians that participated in the study and the ones that did not. Most respondents were in practice for more than 10 years (62%), graduated from US schools (71%) and had their residency training in academic centers (70%). While 75% had never been sued, 90% knew somebody who had. Most physicians (85%) thought they had at least a 1% chance of being sued in the next 10 years and that defensive medicine could decrease this risk.

Table 1. Physicians characteristics.

Of the 1234 orders, 89.8% (n = 1108) were rated as not at all defensive, 9.5% (n = 117) were somewhat defensive (1 and 2 on the scale), and only 0.8% (n = 9) were mostly or completely defensive (3 and 4 on the scale).

Physicians had a median defensiveness score of 0.018 (IQR = [0.008, 0.049]) with 3.1% (IQR = [0.5%, 7.2%]) of the total cost of orders attributable to defensive medicine. Compared to physicians whose defensiveness scores were below the median, those with scores above the median wrote similar numbers of orders (3.4 ± 0.9 vs 3.7 ± 1.1, p = 0.41) and had similar total costs ($239.9 ± 93.2 vs $243.9 ± 61.0, p = 0.91) per visit (). Moreover, visits with number of orders above (4.4 ± 0.5) and below (2.8 ± 0.6) the median of 3.5 had similar proportions of cost due to defensiveness (0.04 ± 0.03 vs 0.10 ± 0.19, p = 0.35, respectively).

Table 2. Summary of outcomes.

The association between physician characteristics and defensive orders is shown in . In the random-effect logistic model, physicians were more likely to place defensive orders if trained in community hospitals vs academic centers (OR = 4.29; 95% CI = 1.55–11.86; p = 0.01). Gender, number of years in practice, place of medical school, having been involved in medical litigations, and fear of being sued were not associated with defensive orders.

Table 3. Association between physician characteristics and defensive orders. The logistic model contains a random effect for the provider to account for the possible correlation among repeated orders placed by each physician.

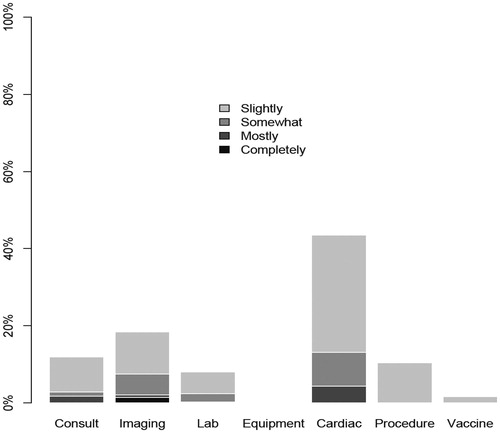

Patient characteristics associated with defensive orders are presented in . Female patients were more likely than male patients to be treated defensively (OR = 1.69; 95% CI = 1.06–2.70; p = 0.03). Medicaid patients were more likely to receive defensive orders than privately insured patients (OR = 4.98; 95% CI = 1.17–21.26; p = 0.03), but there was no significant difference between privately insured and Medicare (OR = 0.95; 95% CI = 0.61–1.49; p = 0.83) or self-pay (OR = 0.55; 95% CI = 0.21–1.42; p = 0.22) patients. Within each category, cardiac diagnostic orders had the highest proportion of the defensive orders (43.5%), followed by imaging (18.4%) and procedures (10.4%). When compared with administered vaccines, diagnostic cardiology orders (OR = 70.02; 95% CI = 7.33–669.17; p < 0.001) and imaging orders (OR = 14.19; 95% CI = 1.76–114.27; p = 0.013) were more likely to be defensive. The most common defensive cardiology orders were electrocardiogram for diagnoses such as fatigue, chest pain, or hypertension, echocardiogram for fatigue, and exercise stress test for palpitations, or shortness of breath, respectively. In the imaging category the top defensive orders were computed tomography, ultrasound, and X-ray of the abdomen for abdominal pain, and X-ray of the lumbar spine for low back pain. The proportion of orders deemed to be defensive by order type is shown in .

Table 4. Association between patient characteristics and defensive orders. The logistic model contains a random effect for provider to account for the possible correlation among repeated orders placed by each physician.

Discussion

In this study, we describe a new method to directly quantify the proportion of medical cost associated with defensive medicine in the general medicine outpatient setting. The methodology can be easily applied to other medical specialties, both in the inpatient and outpatient setting. In contrast to other studiesCitation14, we found that, in this primary care setting, the impact of defensive medicine on the total medical cost is very small and probably contributes little to rapidly rising healthcare costs.

Interestingly, the total cost appears to be the same whether or not physicians consider their practice to be defensive. One possible explanation for this paradox is that highly defensive physicians place more defensive orders but fewer non-defensive ones. Alternatively, less defensive physicians may not be fully aware of the reasons for some of their orders, mistaking caution for the standard of care. Recently published studies showed that most physicians believe that the fear of malpractice lawsuits generates unnecessary testing and proceduresCitation15, even in states with medical liability damage capsCitation16. Unfortunately, our ability to assess physician characteristics or beliefs associated with defensive ordering was limited by our small sample size. Although physicians in our study who placed more defensive orders were more likely to have been sued, to know someone who was sued, to worry about being sued, and to believe that defensive medicine could reduce the risk of being sued, none of these associations reached statistical significance. One place that physicians learn about malpractice is from residency programsCitation17. Our finding that physicians who trained in community programs practiced more defensively may reflect an emphasis on defensive medicine practice in these programs. Moreover, community physicians might worry more about malpractice liability and convey those concerns to trainees. Alternatively, physicians trained in academic centers may be used to ordering the same tests, without necessarily considering them defensive.

Our finding that physicians practiced less defensively when caring for men was unexpected and appears to be novel. Women can have atypical clinical presentationsCitation18 and this might justify ordering more tests, even in the absence of litigation. However, the atypical presentations could also activate the defensive mechanisms and make physicians order tests to prevent missing a diagnosis, even when they believe the probability of that diagnosis to be extremely low. It might also be due to physician awareness of the facts that, compared to men, women undergo fewer screening proceduresCitation19 and diagnostic tests for certain conditionsCitation20,Citation21 and consequently have more missed diagnoses. Alternatively, women might be better informed than men about some medical conditionsCitation22 and request more testingCitation23. Physicians may not consider these tests appropriate, but order them anyway out of fear of malpractice claims should one of them later prove to have been justified.

The association between a specific type of patient insurance and defensive medicine indicates that conclusions drawn from studies that assessed Medicare and Medicaid claims might not apply to patients with other types of medical coverage. Our finding of placing more defensive orders for Medicaid patients is novel and might be related to the false belief that Medicaid patients are more likely than non-Medicaid patients to file liability claimsCitation24. Another analysis, limited to patients with skull fractures, found that physicians ordered more tests and procedures for Medicaid patients, a finding that could be attributed to defensive medicineCitation25.

Commonly missed or delayed adult diagnoses in the primary care setting include cancer and myocardial infarctionCitation26. This might explain why cardiology and radiology tests had the highest probability of being rated defensive, whereas vaccines were the least defensive. Our finding of a higher number of defensive orders in the imaging and cardiology categories could also be explained by a lack of guidelines and recommendations for non-specific symptoms such as fatigue or abdominal pain. Moreover, it could be due to the awareness of the severe consequences of missed cardiac disease. In addition, the fear of litigation could discourage the providers from ordering the vaccinesCitation27, particularly for some categories of patientsCitation28.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study sample was small and only 42% of the invited physicians completed the study. It seems likely that physicians who felt that defensive medicine was a problem might be more likely to participate, and thus our estimate of even the small proportion of costs due to defensive medicine may be too high. Alternatively, if more defensive physicians self-selected out of the survey because of concern about exposing their defensiveness, our results may be biased downward. Moreover, the reliance on the subjective assessment of defensiveness by the ordering physicians without an objective assessment of the appropriateness of the orders by other physicians is a potential source of bias. The physician training, organizational culture of the place where they practice could result in defensive practices that are not recognized as such by physicians. Another limitation is that physicians in the study were employed by a single healthcare system and the results might be different in other states or practice settings. However, the number of medical-malpractice claims against Cleveland Clinic physicians is comparable with the total number filled in the state of Ohio (e.g., 1.6 claims vs 2.36 claims per 10,000 patients in 2012, respectively). Additionally, the physicians belonged exclusively to primary care specialties; behavior may differ in other, higher-risk specialties. Still, in the US, general practice ranks in the top five specialties of the number of malpractice claims and difficulty of defending the claimsCitation26, with more cases settled or resulting in a verdict for the plaintiffCitation29.

Conclusion

The present study provides a novel tool to quantify the proportion of medical cost associated with defensive medicine. This method can be easily applied to any specialty, both in the outpatient and inpatient settings. Specifically in the primary care setting, the cost of defensive medicine found in our study is much less than previously reported and appears to have little impact on rapidly rising healthcare costs. However, further exploration of the gender and insurance findings as well as assessing the cost of defensive medicine among other healthcare systems, specialties, and settings is needed.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was not funded.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

None of the authors have any relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (22.4 KB)Acknowledgments

No assistance in the preparation of this article is to be declared. This data was presented at the 37th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, April 23–26, 2014, San Diego, USA.

References

- Defensive Medicine. Merriam-Webster Online. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/defensive%20medicine. Accessed 24 December 2013

- WHO. World health statistics 2011. Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2011/en/index.html. Accessed December24, 2013

- A Costly Defense: Physicians Sound Off On The High Price of Defensive Medicine in the U.S. Jackson Healthcare 2011. http://www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/8968/defensivemedicine_ebook_final.pdf. Accessed 24 December 2013

- Kessler DP, McClellan MB. Do doctors practice defensive medicine? Q J Econ 1996;111:353-90

- Baicker K, Fisher ES, Chandra A. Malpractice liability costs and the practice of medicine in the Medicare program. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:841-52

- Sloan FA, Shadle JH. Is there empirical evidence for “Defensive Medicine”? A reassessment. J Health Econ 2009;28:481-91

- Kavanagh KT, Calderon LE, Saman DM. The relationship between tort reform and medical utilization. J Patient Saf 2013. Published online Oct 7

- Baldwin LM, Hart LG, Lloyd M, et al. Defensive medicine and obstetrics. JAMA 1995;274:1606-10

- Klingman D, Localio AR, Sugarman J, et al. Measuring defensive medicine using clinical scenario surveys. J Health Polit Policy Law 1996;21:185-217

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA 2005;293:2609-17

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule. Baltimore, MD. 2013. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/clinlab.html. Accessed September 26, 2013

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics/Orthotics & Supplies Fee Schedule. Baltimore, MD. 2013. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/DMEPOSFeeSched/index.html. Accessed September 26, 2013

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Physician Fee Schedule. Baltimore, MD. 2013. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/index.html. Accessed September 26, 2013

- Segal J. Defensive medicine: a culprit in spiking healthcare costs. Med Econ 2012;89:70-1

- Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. Physicians’ views on defensive medicine: a National Survey. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1081-3

- Carrier ER, Reschovsky JD, Katz DA, et al. High physician concern about malpractice risk predicts more aggressive diagnostic testing in office-based practice. Health Aff 2013;32:1383-91

- O'Leary KJ, Choi J, Watson K, et al. Medical students' and residents' clinical and educational experiences with defensive medicine. Acad Med 2012;87:142-8

- Collins P, Vitale C, Spoletini I, et al. Gender differences in the clinical presentation of heart disease. Curr Pharm Des 2011;17:1056-8

- Gancayco J, Soulos PR, Khiani V, et al. Age-based and sex-based disparities in screening colonoscopy use among medicare beneficiaries. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:630-6

- Hirakawa Y, Masuda Y, Kuzuya M, et al. Age differences in the delivery of cardiac management to women versus men with acute myocardial infarction: an evaluation of the TAMIS-II data. Int Heart J 2006;47:209-17

- Chang AM, Mumma B, Sease KL, et al. Gender bias in cardiovascular testing persists after adjustment for presenting characteristics and cardiac risk. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:599-605

- Hoffman RM, Lewis CL, Pignone MP, et al. Decision-making processes for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer screening: the DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Making 2010;30(5 Suppl):53S-64S

- Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Couper MP, Singer E, et al. The DECISIONS study: a nationwide survey of United States adults regarding 9 common medical decisions. Med Decis Making 2010;30(5 Suppl):20S-34S

- Baldwin LM, Greer T, Wu R, et al. Differences in the obstetric malpractice claims filed by Medicaid and non-Medicaid patients. J Am Board Fam Pract 1992;5:623-7

- Hennesy K. The effects of malpractice tort reform on defensive medicine. Issues Polit Econ 2004;13. Available at http://org.elon.edu/ipe/Henessey_Edited.pdf. Accessed 6 March 2014

- Wallace E, Lowry J, Smith SM, et al. The epidemiology of malpractice claims in primary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002929

- Craig L, Elliman D, Heathcock R, et al. Pragmatic management of programmatic vaccination errors–lessons learnt from incidents in London. Vaccine 2010;29:65-9

- Blanchard-Rohner G, Siegrist CA. Vaccination during pregnancy to protect infants against influenza: why and why not? Vaccine 2011;29:7542-50

- Schiff GD, Puopolo AL, Huben-Kearney A, et al. Primary care closed claims experience of Massachusetts malpractice insurers. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:2063-8