Abstract

Objective:

To assess the cost-effectiveness of natalizumab vs fingolimod over 2 years in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) patients and patients with rapidly evolving severe disease in Sweden.

Methods:

A decision analytic model was developed to estimate the incremental cost per relapse avoided of natalizumab and fingolimod from the perspective of the Swedish healthcare system. Modeled 2-year costs in Swedish kronor of treating RRMS patients included drug acquisition costs, administration and monitoring costs, and costs of treating MS relapses. Effectiveness was measured in terms of MS relapses avoided using data from the AFFIRM and FREEDOMS trials for all patients with RRMS and from post-hoc sub-group analyses for patients with rapidly evolving severe disease. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess uncertainty.

Results:

The analysis showed that, in all patients with MS, treatment with fingolimod costs less (440,463 Kr vs 444,324 Kr), but treatment with natalizumab results in more relapses avoided (0.74 vs 0.59), resulting in an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of 25,448 Kr per relapse avoided. In patients with rapidly evolving severe disease, natalizumab dominated fingolimod. Results of the sensitivity analysis demonstrate the robustness of the model results. At a willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of 500,000 Kr per relapse avoided, natalizumab is cost-effective in >80% of simulations in both patient populations.

Limitations:

Limitations include absence of data from direct head-to-head studies comparing natalizumab and fingolimod, use of relapse rate reduction rather than sustained disability progression as the primary model outcome, assumption of 100% adherence to MS treatment, and exclusion of adverse event costs in the model.

Conclusions:

Natalizumab remains a cost-effective treatment option for patients with MS in Sweden. In the RRMS patient population, the incremental cost per relapse avoided is well below a 500,000 Kr WTP threshold per relapse avoided. In the rapidly evolving severe disease patient population, natalizumab dominates fingolimod.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic and disabling disorder of the central nervous system with considerable economic and social impact. In Europe, MS has an average annual incidence of 4.3 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. The estimated prevalence rate for the past 3 decades has been in the area of 83 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Higher rates are observed in Northern countries and in females, with a ratio of two females for one maleCitation1.

Relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is the most frequently diagnosed form of MS, representing 80–85% of incident casesCitation1,Citation2. It is a clearly defined disease, with relapses followed by recovery and periods between relapses characterized by a lack of disease progression. Relapses occur throughout the course of the disease, resulting in an accumulation of physical disability and cognitive decline.

Disability related to MS is measured using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), a scale ranging from 0–10, with the most severely impaired patients showing the highest scores and a change of 1.0 point or more interpreted as clinically meaningfulCitation3. The most disabled patients have been shown to incur higher costs than the less disabled ones and to have a more affected quality-of-lifeCitation4,Citation5. Given the chronic nature of the disease and its propensity to occur in young adults, the burden of the disease will be substantial over the patient’s life.

A multinational prospective study in nine European countries assessed the costs and quality-of-life of MS patientsCitation4. Based on the results of that multi-national study, Sobocki et al.Citation6 extrapolated the total annual cost of MS in 28 European countries to be ∼€12.5 billion in 2005, or €27 per inhabitant. It was estimated by the authors that ∼56% of total costs were direct medical costs, and the remaining portion was composed of informal care and indirect costs due to disability. The cost of medications was estimated at €2.5 billion, comprising 22% of the total costs. Although disease-modifying medications comprise a significant proportion of the MS treatment costs, they were shown to considerably decrease the number of relapses and have become an integral part of MS treatment.

Relapses have been shown to be frequently associated with increased disability. It is estimated that 42% of patients experiencing a relapse will suffer from a residual impairment of at least 0.5 EDSS units, and 28% will suffer from a residual impairment of 1 EDSS unit or moreCitation7, leading to a loss of quality-of-life due to exacerbation and increased costs. Relapse episodes are also associated with increased costs that vary across countries, depending on how they are managedCitation4. Reducing the number of relapses is, therefore, beneficial in terms of improving patient quality-of-life, delaying the progression of disability, and reducing cost related to the management of relapses. Management strategies that can help to reduce the frequency and/or severity of relapses have the potential to reduce the overall cost burden of the disease.

Healthcare decision-makers in Europe and worldwide must continue to make reimbursement decisions under increasingly strong budget constraints. Considering the important economic impact of MS, and the evolving MS treatment landscape, there is a need to evaluate disease-modifying therapies in terms of costs, safety, and clinical effectiveness.

Beta-interferon and glatiramer acetate have been on the European markets for decades and have demonstrated efficacy and safety for RRMSCitation8. Two more recently approved treatments for RRMS are natalizumab, an infused integrin receptor antagonist, and fingolimod, an oral sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator.

According to the European Medicines Agency, natalizumab and fingolimod are indicated for use in adult patients with highly active RRMS, which can be defined as either: (1) high disease activity despite treatment with a beta-interferon, or (2) with rapidly evolving severe RRMS defined by two or more disabling relapses in 1 year and with one or more gadolinium-enhancing lesions on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or a significant increase in T2 lesion load compared to a previous recent MRI.

While the safety profiles of beta-interferons and glatiramer acetate are well known, there are higher risks of potentially severe adverse events associated with natalizumab and fingolimod. Natalizumab has been associated with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), and fingolimod has been associated with bradyarrhythmia and atrioventricular block at treatment initiation, infections, macular edema, respiratory effects, and hepatic effects, as well as an observed higher rate of skin cancers in clinical trialsCitation9–11.

Accordingly, there is a need to compare the relative value of newer MS therapies, such as fingolimod and natalizumab, in terms of cost, safety, and effectiveness, given healthcare resource constraints. Previous models comparing disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), including natalizumab, have been developedCitation12,Citation13 and found natalizumab to be the most cost-effective therapy in terms of cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) for patients with MS in the UKCitation12, and as measured by cost per relapse avoided from the perspective of a US managed care payerCitation13. O’Day et al.Citation14 developed an evidence-based economic model to assess the incremental cost-effectiveness of natalizumab and fingolimod based on clinical trial data for patients with RRMS, and found that natalizumab dominates fingolimod in terms of incremental cost per relapse avoided from the US payer perspective.

Utilization of DMTs varies significantly by country. In the UK it was estimated that 21% of MS patients receive DMTs compared to 50% in SwedenCitation15. Accordingly, the objective of this study was to assess the cost per relapse avoided of natalizumab and fingolimod in Sweden, a high utilization country, to provide payers with health economic data for decision-making.

Methods

Model design

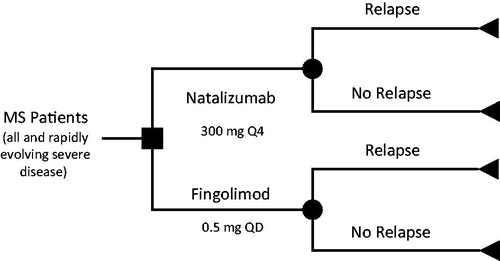

A decision analytic model was developed to estimate the cost-effectiveness of monotherapy with natalizumab and fingolimod used in RRMS from the Swedish payer perspective (see ). Separate analyses were conducted for patients with rapidly evolving severe MS and all patients with MS in Sweden. A 2-year time horizon was employed in the model to correspond with the duration of the clinical trials used to populate the model. Although it is recognized that MS is a chronic disease that progresses throughout a patient’s lifetime, extrapolations beyond the available trial data were not undertaken. The two agents included in this model for comparison were natalizumab 300 mg administered intravenously (IV) once every 4 weeks, and fingolimod 0.5 mg administered orally once daily. Dosing for each agent was based upon approved prescribing informationCitation16,Citation17.

Relapses pose a substantial burden to the patient and are often associated with considerable use of healthcare resources; thus, they were selected as the primary clinical outcome of interest for inclusion in the model. Relapse rates in the model were obtained from the AFFIRM and FREEDOMS trials, published pivotal phase 3 trials comparing natalizumab and fingolimod, respectively, to placebo, with the majority being treatment-naïve patientsCitation18,Citation19. Total 2-year costs of therapy were estimated based on acquisition costs, administration costs, and monitoring costs. Although severe adverse events (SAEs) have occurred in patients receiving natalizumab and fingolimod, the incidence of such complications was extremely low (<1% for all SAEs for both natalizumab and fingolimod, with the exception of relapse of MS)Citation18,Citation19, and, while their clinical and humanistic impact is significant, the costs associated with their management are unlikely to have a significant economic impact on a health system and were, therefore, excluded from the economic model.

The relevant outcome of the model was the incremental cost per relapse avoided for natalizumab compared to fingolimod.

Model inputs

Drug acquisition costs

The costs per package, drug costs, and 2-year drug costs were determined based on prices published by the Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency (TLV), Sweden’s national reimbursement authorityCitation20. Published prescribing information was used to determine the number of doses per package and number of packages per yearCitation16,Citation17. Drug acquisition costs for natalizumab were calculated based on 13 packages per year, one dose per package. Acquisition costs for fingolimod were calculated based on 13 packages per year, 28 doses per package. Real-world adherence patterns were not available for fingolimod at the time the model was developed. Therefore, to be conservative, patients were assumed to be 100% adherent to natalizumab and fingolimod in the model, maximizing the drug costs for each agent. Drug acquisition costs in 2011 Swedish kronor (Kr) were obtained from the TLV pricing database and were 409,936 Kr for both natalizumab and fingolimod.

Drug administration and monitoring costs

To account for differences in the routes of administration for natalizumab (1-h IV administration requiring supervision by a healthcare provider) and fingolimod (oral), the model included the 2-year costs of drug administration for every 4-week-infusion of natalizumab and no administration cost for fingolimod. Twenty-six administrations of natalizumab are expected over the 2-year time horizon. Administration costs used are displayed in .

Table 1. 2-year drug administration and monitoring inputs for natalizumab and fingolimod in Sweden.

Sweden-specific monitoring cost items were incorporated into the model for both the natalizumab and fingolimod. These include laboratory tests, imaging, physician office visits required or recommended (based on the prescribing information), and other costs that were based on guidelines and published literature. The utilization of monitoring resources and their associated costs are listed in .

Efficacy input

The efficacy outcome included in the model was the anticipated reduction in relapses over the 2-year model time horizon. The model used data from published clinical trials, AFFIRM and FREEDOMS, to estimate these rates in all patientsCitation18,Citation19, and from post-hoc sub-group analyses from AFFIRM and FREEDOMS for patients with rapidly evolving severe diseaseCitation21,Citation22. In AFFIRM, relapses were defined as new or recurrent neurologic symptoms not associated with fever or infection, which lasted for at least 24 h and were accompanied by new neurologic signs found by the examining neurologistCitation21. In FREEDOMS, relapses were defined as symptoms accompanied by an increase of at least half a point in the EDSS score, or an increase of one point in each of two EDSS functional-system scores, or an increase of two points in one EDSS functional-system score (excluding scores for the bowel/bladder or cerebral functional systems)Citation19.

Because there are no head-to-head studies comparing the efficacy of natalizumab and fingolimod, we conducted this indirect comparison in which we adjusted for the placebo relapse rate from AFFIRM and FREEDOMS. For comparison purposes, the model utilized the number of relapses over 2 years that occurred in the placebo treatment arms during the phase 3 clinical trials for natalizumab and fingolimod and the number of patients in each placebo group to calculate the weighted average number of relapses per patient prior to treatment with either agent. The weighted average number of relapses per patient with rapidly evolving severe MS prior to treatment was calculated to be 1.19; in all patients with MS, the weighted average number of relapses per patient was calculated to be 0.54. The relative reduction in relapse rate was obtained for natalizumab and fingolimod from the intent-to-treat population of the respective phase 3 clinical studiesCitation18,Citation19,Citation21,Citation22. The number of relapses avoided with treatment was calculated as the weighted average number of relapses per patient prior to treatment multiplied by the relapse rate reduction for natalizumab and fingolimod. On that basis, the relapse rate reduction was estimated to be 81% for natalizumab, and 67% with fingolimod in the rapidly evolving severe population and 68% with natalizumab and 54% with fingolimod in all patients with RRMS. The number of relapses per patient that could be anticipated to occur during 2 years of therapy was then calculated as the weighted average number of relapses per patient prior to treatment, minus the number of relapses avoided with treatment.

Cost of treating MS relapse

The cost of treating an MS relapse was also included in the model. As the severity of the relapse affects the level and intensity of management required, it was assumed that all patients experiencing a relapse require medium-intensity medical management (emergency room [ER] visit, observational unit, or acute treatments such as IV medications, e.g. steroids, in either an outpatient or home setting)Citation23. Based on literature-derived values, medically managing a relapse at a medium-intensity level cost 31,635 Kr per relapseCitation4.

The cost of treating relapses per patient was calculated as the anticipated number of relapses per patient during 2 years of therapy multiplied by the weighted average cost of managing an MS relapse.

Incremental cost per relapse avoided

The incremental cost per relapse avoided was calculated as the difference between natalizumab and fingolimod in the total 2-year cost of therapy divided by the difference between natalizumab and fingolimod in the number of relapses avoided over 2 years.

Sensitivity analysis

A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the joint uncertainty of all model parameters simultaneously. Relative relapse rate reductions were modeled using a log-normal distribution, costs were modeled using normal distributions, and the monitoring resources utilized were modeled using gamma distributions. Parameter ranges for the probabilistic distributions were determined using the 95% confidence intervals (CIs), where data were available (relative relapse rate reductions and cost of treating MS relapses).

For drug acquisition and administration costs, a range of ±10% of the base-case value was assumed. For resource utilization inputs, a range of ±50% of the base-case value was assumed, to reflect the greater uncertainty around these parameters. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis was run with 1000 Monte Carlo simulations, and a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve was generated over a range of willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds from 0 Kr to 500,000 Kr per relapse avoided.

Results

The 2-year costs per patient, number of relapses avoided per patient, and cost per relapse avoided are shown in . The cost-effectiveness analysis showed that, in patients with rapidly evolving severe disease, natalizumab dominates fingolimod, as it is less costly and more effective. Over a 2-year time horizon, natalizumab cost 1865 Kr less than fingolimod and resulted in 0.33 more relapses avoided (1.92 relapses avoided for natalizumab vs 1.59 relapses avoided for fingolimod). In all patients with MS, although fingolimod costs less than natalizumab (440,463 Kr vs 444,324 Kr), natalizumab is more effective (0.15 more relapses avoided with treatment with natalizumab), resulting in an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of 25,448 Kr per relapse avoided.

Table 2. Total costs per patient and relapses avoided per patient.

Results of the probabilistic sensitivity analysis displayed in generally support the deterministic results. However, in the probabilistic analysis, the mean cost of natalizumab (448,153 Kr) was slightly higher than the mean cost of fingolimod (447,870 Kr) among patients with rapidly evolving severe disease, with a corresponding probability that natalizumab was less costly than fingolimod of 0.469 among all patients and 0.489 among patients with rapidly evolving severe disease. The probability that natalizumab was more effective than fingolimod was 0.980 among all patients and 0.853 among patients with rapidly evolving severe disease. The probability that natalizumab was more cost-effective than fingolimod across a range of WTP thresholds is displayed in .

Table 3. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis results.

Discussion

This model estimated the incremental cost per relapse avoided of natalizumab and fingolimod from the perspective of the Swedish healthcare system. Sweden is a country with high utilization of DMTs. Results of the base-case analysis demonstrated that, in patients with rapidly evolving severe MS, natalizumab dominated fingolimod, as it was less costly and more effective over a 2-year time horizon. In all patients with MS, natalizumab was more costly but more effective, resulting in an ICER of 25,448 Kr per relapse avoided.

The difference in the total 2-year cost of therapy per patient was partially attributable to drug costs; natalizumab is sold at the same price as fingolimod in Sweden (406,936 Kr). When excluding the cost of relapses, the additional administration costs made natalizumab marginally more expensive; however, natalizumab was more effective at avoiding relapses than fingolimod in both rapidly evolving severe and all RRMS patients. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis was consistent with the base-case deterministic analysis, with the exception that natalizumab did not strictly dominate fingolimod among patients with rapidly evolving severe disease. In the case of a more costly and more effective therapy, cost-effectiveness analyses must be evaluated with reference to a decision-maker’s WTP threshold for the outcome in question. Since a WTP threshold per relapse avoided has not been established in Sweden, WTP was assessed across a wide range of values from 0 Kr to 500,000 Kr per relapse.

Although other models examining the cost-effectiveness of MS treatments have been developed, given differences in comparators, methodological design, and model assumptions, it may be difficult to compare this model to other published models. Goldberg et al.Citation24 evaluated first-line injectable DMTs used for the treatment of relapsing MS in terms of cost per relapse avoided over a 2-year time horizon using methodology similar to this model. Other studies have evaluated natalizumab against injectable DMTs. Gani et al.Citation12 examined the cost-effectiveness of natalizumab compared to injectable DMTs with regard to estimating transitions between disability states and the probability of relapse within each state. Using QALYs as the outcome measurement, they determined that natalizumab may be a cost-effective therapy for patients with MS in the UK. Chiao and MeyerCitation13 found natalizumab to be the most cost-effective therapy with regard to relapses avoided when modeled against other available injectable DMTs, including interferon beta-1a (IFNβ-1a) 30 mg intramuscular once weekly, interferon beta-1b (IFNβ-1b) 0.25 mg subcutaneous (SC) every other day, glatiramer acetate 20 mg SC once daily, and IFNβ-1a 44 mg SC 3-times weekly, from the perspective of a US managed care payer. In their study, the average cost per relapse avoided was $56,594 for natalizumab and ranged from $87,791–$103,665 for the other DMTs.

Two studies to date have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of fingolimod in comparison to IFNβ-1a. Lee et al.Citation25 used a Markov model to compare fingolimod to intramuscular IFNβ-1a from a US societal perspective. The authors evaluated both relapses avoided and QALYs and determined that, although fingolimod was associated with fewer relapses (0.41 vs 0.73 per patient per year) and more QALYs gained (6.7663 vs 5.9503), it came at a higher cost ($565,598 vs $505,234), resulting in an ICER of $73,975 per QALY. However, delaying treatment with fingolimod was shown to be less effective in another model. Agashivala and Kim Citation26 estimated the average cost per relapse avoided to be $83,125 for 2 years with continuous treatment with fingolimod compared to $103,624 for first-year treatment with IFNβ-1a and second-year treatment with fingolimod. However, fingolimod was not compared to natalizumab in either study. Another study by Bergvall et al.Citation27 conducted a cost-minimization analysis comparing natalizumab and fingolimod in Sweden. The Bergvall et al. study included treatment costs, monitoring, and lost patient productivity and leisure time. Costs were estimated to be 18% higher for natalizumab over 1 year. However, the Bergvall et al. study did not include effectiveness as an outcome or its impact on costs of treating relapses, hence the differences with the present study. The current study was designed to address these shortcomings.

As the life expectancy of patients with MS is not typically reduced, healthcare decision-makers in all countries may incur costs associated with these patients over several decades. Given that healthcare resources are constrained, these healthcare decision-makers are often looking for opportunities to manage certain therapeutic categories, including MS, in an attempt to control costs. In addition, as more agents become available for the treatment of MS, demonstrating clinical efficacy while controlling costs will be important to healthcare decision-makers around the world. With the oral agent fingolimod in the treatment landscape for MS, questions will arise as to the potential benefits an oral therapy may offer compared to physician- and self-administered injectable therapies that are already approved to treat MS.

In the absence of head-to-head comparative data between natalizumab and fingolimod, a decision analysis such as this provides insight into a comparison of the efficacy and costs associated with each of the therapies. This insight may be used to guide healthcare decision-makers with regard to evaluating the benefits of one therapy vs the other. The results of this model demonstrate that natalizumab is cost-effective and may result in cost savings compared to fingolimod in Sweden for all patients with MS and for patients with rapidly evolving severe MS. In both patient populations, at a WTP threshold of 50,000 Kr per relapse avoided, natalizumab is more likely cost effective compared to fingolimod, rising to greater than an 80% probability of being cost effective at a WTP threshold of 500,000 Kr. Moreover, the model results would be conservative and under-estimate the difference if there is a residual neurologic deficit associated with relapses in the natural history of MS.

Limitations

The first limitation of this model is the absence of direct head-to-head studies comparing natalizumab and fingolimod. Relapse rates used in the model were derived from the respective clinical trials for natalizumab and fingolimod. Therefore, differences in study designs, study procedures, or baseline characteristics may have an impact on these rates, and results should be interpreted with this in mind. However, the analysis attempted to control for these differences through the use of an indirect placebo-adjusted comparison of relapse rates. In addition, although the definition of relapse in FREEDOMS includes an increase in EDSS score, unlike AFFIRM, the definition of relapse did not include one new neurological sign found by an examining neurologist. Use of the relative reduction in relapse rate was thought to be most appropriate and has been used in other models, such as the model by Goldberg et al.Citation24. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses were conducted to demonstrate the robustness of the model to changes in inputs, such as the relative reduction in relapse rate.

A second limitation was the use of relapse rate reduction as the primary outcome of the model, rather than sustained disability progression. Disability progression varies among patients, and operational definitions for disability progression were not consistent between natalizumab and fingolimod clinical trialsCitation18,Citation19. The economic impact of an MS relapse does not fully represent the burden of this chronic, debilitating disease that results in disability progression over time. Although the use of disability progression and QALYs could potentially address this concern, it would require a very different model framework and additional data/assumptions and would add complexity to this analysis.

A third limitation of the model is that it assumes patients are 100% adherent to treatment. Real-world studies estimate that adherence rates for MS therapies range from 42–60% at 1 year after treatment initiationCitation28. Adherence data for natalizumab and fingolimod were not available at the time this model was developed. In theory, natalizumab may have a higher adherence rate than other therapies as a result of the administration requirements that mandate the once every 4 weeks IV infusion under the supervision of a healthcare professional. The administration of natalizumab by a healthcare professional may increase the likelihood that patients receive treatment compared to a self-administered oral agent that must be taken once daily. However, given the lack of available adherence data, the model conservatively assumed 100% adherence for both agents.

A fourth limitation was that the costs of adverse events were not captured in the model. Progressive multi-focal leukoencephalopathy has occurred in patients treated with natalizumab; however, the costs associated with managing the complication would be expected to have minimal impact on costs due to the rare occurrence of this serious adverse event. In addition, although fingolimod is associated with adverse events such as reduction in heart rate, atrioventricular block, infection, macular edema, and a decrease in pulmonary function tests, until additional data are collected, it is unclear how these potential adverse events may affect costs or if any other adverse effects will be characterized.

Conclusions

The results of this model suggest that total treatment costs of natalizumab are approximately the same as for the oral agent fingolimod. The products have identical drug costs in Sweden, with the higher administration costs of natalizumab offset by lower costs of managing relapses. However, natalizumab is more effective than fingolimod in all MS patients and those with rapidly evolving severe disease. The result is that natalizumab either dominates fingolimod or is cost-effective in these patient populations. In the absence of head-to-head comparisons between agents, economic models may be useful tools for European payers facing the challenges of offering the best care for patients under limited financial resources.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Biogen Idec Inc. (Cambridge, MA) provided funding for this study. CW is an employee of Biogen Idec.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Xcenda, a consulting company, received funding from Biogen Idec to assist in completion of this study. KO’D & KM are employees of Xcenda. DS-M was an employee of Xcenda at the time this study was completed. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Annette Andrén for providing the Swedish cost data and reviewing the manuscript.

References

- Pugliati M, Rosari G, Carton H, et al. The epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Eur J Neurol 2006;13:700-22

- Sudstrom P, Svenningsson A, Nystrom L, et al. Clinical characteristics of multiple sclerosis in Vasterbotten County in northern Sweden. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:711-16

- Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983;33:1444-52

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, et al. Cost and quality of life in multiple sclerosis in Europe: method of assessment and analysis. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7(2 Suppl):5-13

- Patwardhan MB, Matchar DB, Samsa GP, et al. Cost of multiple sclerosis by level of disability: a review of literature. Mult Scler J 2005;11:232-9

- Sobocki P, Pugliati M, Lauer K, et al. Estimation of the costs of MS in Europe: extrapolations from a multinational cost study. Mult Scler 2007;13:1054-64

- Lublin FD, Baier M, Cutter G. Effects of relapses on development of residual deficit in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2003;61:1528-32

- Kieseier BC, Stüve O. A critical appraisal of treatment decisions in multiple sclerosis – old versus new. Nature Rev Neurol 2011;7:255-62

- Cohen JA, Barkhof F, Comi G, et al; for the TRANSFORMS study group. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. New Engl J Med 2010;362:402-15

- Comi G, O’Conner P, Montalban X, et al. Phase II study of oral fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis: 3-year results. Mult Scler 2010;16:197-207

- Portaccio E. Evidence-based assessment of potential use of fingolimod in treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. Core Evidence 2010;6:13-21

- Gani R, Giovannoni G, Bates D, et al. Cost-effectiveness analyses of natalizumab (Tysabri) compared with other disease-modifying therapies for people with rapidly evolving severe relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis in the UK. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:617-27

- Chiao E, Meyer K. Cost effectiveness and budget impact of natalizumab in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:1445-54

- O’Day K, Meyer K, Miller R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of natalizumab versus fingolimod for the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. J Med Econ 2011;14:617-27

- Naci H, Fleurette R, Birt J, et al. Economic burden of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics 2010;28:363-79

- Novartis Pharma GmbH. Gilenya summary of product characteristics. European Medicines Agency. Nuremberg, Germany. 2011. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002202/WC500104528.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2012

- Biogen Idec Denmark Manufacturing ApS. Tysabri summary of product characteristics. European Medicines Agency. Hillerød, Denmark. 2011. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000603/WC500044686.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2012

- Polman CH, O’Connor PW, Havrdova E, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. New Engl J Med 2006;354:899-910

- Kappos L, Radue EW, O’Connor P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. New Engl J Med 2010;362:1-15

- Pricing database. Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency, TLV. http://www.tlv.se/beslut/sok/lakemedel/. 2011. Accessed March 9, 2012

- Hutchinson M, Kappos L, Calabresi PA, et al. The efficacy of natalizumab in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: subgroup analyses of AFFIRM and SENTINEL. J Neurol 2009;256:405-15

- Devonshire V, Havrdova E, Radue EW, et al. Relapse and disability outcomes in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod: subgroup analyses of the double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled FREEDOMS study. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:420-8

- O’Brien JA, Ward AJ, Patrick AR, et al. Cost of managing an episode of relapse in multiple sclerosis in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res 2003;3:17-28

- Goldberg LD, Edwards NC, Fincher C, et al. Comparing the cost-effectiveness of disease-modifying drugs for the first-line treatment of relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Pharm 2009;15:543-55

- Lee S, Baxter DC, Roberts MS, Coleman CL. Cost-effectiveness of fingolimod versus interferon beta-1a for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis in the United States. J Med Econ 2012;15:1088-96

- Agashivala N, Kim E. Cost-effectiveness of early initiation of fingolimod versus delayed initiation after 1 year of intramuscular interferon beta-1a in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Ther 2012;34:1583-90

- Bergvall N, Tambour M, Henriksson F, et al. Cost-minimization analysis of fingolimod compared with natalizumab for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in Sweden. J Med Econ 2013;16:349-57

- Kleinman NL, Beren IA, Rajagopalan K, et al. Medication adherence with disease modifying treatments for multiple sclerosis among US employees. J Med Econ 2010;13:633-40