Abstract

Objective:

Although multiple sclerosis (MS) is one of the most common causes of non-traumatic disability among young adults, no published data on its economic and health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) burden is available from Finland. The DEFENSE study aimed to estimate the costs and HRQoL of patients with MS (PwMS) in Finland and explore how these variables are influenced by disease severity and relapses.

Methods:

Overall, 553 PwMS registered with the Finnish Neuro Society, a national patient association in Finland, completed a self-administered questionnaire capturing information on demographics, disease characteristics and severity (Expanded Disease Severity Scale [EDSS]), relapses, resource consumption and HRQoL.

Results:

The PwMS had a mean EDSS score of 4.0. Overall, 44.1% had relapsing-remitting form of the disease (RRMS). The mean age was 53.8 years and 55.7% had retired prematurely due to MS. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) were used by 42.7% of the study population, and 21.5% across all disease types and severities had experienced relapses during the previous year. The mean total annual cost of MS was €46,994, which increased with advancing disease from €10,835 (EDSS score = 0) to €109,901 (EDSS score = 8–9). The mean utility was 0.644. HRQoL decreased with increasing disease severity. Relapses imposed an additional utility decrement among the PwMS with RRMS and EDSS ≤5 and had a trend-like effect on total costs.

Limitations:

The cross-sectional setting did not allow assessment of the significance of relapses in early MS or the use of DMTs on the prognosis of the disease.

Conclusion:

The study confirms previous findings from other countries regarding a significant disease burden associated with MS and provides, for the first time, published numerical estimates from Finland. Treatments that slow disease progression and help PwMS retain employment for a longer duration have the highest potential to reduce the disease burden associated with MS.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic and highly disabling neurological disorder, is the major cause of non-traumatic disability in young adults. In most patients, clinical manifestations indicate the involvement of motor, sensory, visual, and autonomic systemsCitation1. Commonly observed clinical symptoms include fatigue, visual disturbances, limb weakness, gait problems, and neurogenic bladder. A majority of patients with MS (PwMS) are initially diagnosed with a relapsing-remitting form of the disease (RRMS), characterized by unpredictable exacerbations and remissions. RRMS eventually transforms to a secondary progressive form (SPMS) over time, wherein the condition steadily worsens with or without relapses. In less than 20% of the patients the illness is progressive (primary progressive [PPMS]) from onsetCitation1.

Globally, an estimated 2.3 million individuals were affected with MS in 2013Citation2. Owing to its geographical location, Finland belongs to a high-risk MS zone. Moreover, the epidemiology of MS shows considerable geographical variation and the prevalence is particularly high in the western parts of the countryCitation3. A recent epidemiological survey in Finnish Northern Ostrobothnia reported an overall prevalence of 103/100,000 populationCitation4.

Previous cost-of-illness studies from several other countries have demonstrated that MS put enormous economic and quality-of-life (QoL) burden on the patients, the healthcare system, and society as a wholeCitation5–12. Typically, the burden increases with disease progression, with relapses imposing an additional load.

There are significant differences across countries in regard to burden of MS on the total costs, whereas burden on the health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) shows less variabilityCitation7. These findings can be explained by differences in unit costs, treatment practices, the way services are organized, and their availability. For example, there is substantial international variation in the use of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs)Citation13. DMTs, used mainly in mild-to-moderate disease, may appear to strain healthcare budgets in the short-term; however, these effects are counterbalanced by their potential to relieve disease burden in the long-term by reducing the occurrence of relapses and delaying disease progressionCitation6.

Between-country differences highlight the need for local data on service utilization, costs, and HRQoL associated with MS. All these factors are a pre-requisite for informed decision-making within every health- and social-care jurisdiction. The objective of the burden of illness in patients with multiple sclerosis in the Finland (DEFENSE) study was to determine, for the first time, the economic and HRQoL burden of MS in Finland. In addition, the impact of disease severity and relapses on the burden of illness in PwMS was also analysed.

Patients and methods

Study design

This was a retrospective, cross-sectional mail survey, a method adopted in several earlier studies conducted in other countriesCitation5,Citation7–10,Citation14. The study aimed to specifically assess the costs related to MS. The total costs were estimated from a societal perspective, taking into account all direct healthcare, direct non-medical, and productivity costs, irrespective of the payer. Data were collected from PwMS with all levels of disease severity to generate annual per-patient estimates on costs and HRQoL. The results obtained by this ‘bottom-up’ approach can be extrapolated to national level by using existing epidemiological data on disease prevalence and distribution of PwMS according to disease severity, thereby reliably estimating the total costs of MS.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital District of South-Western Finland.

Study participants

The study population included patients registered with the Finnish Neuro Society, a national patient association in Finland. The inclusion criteria comprised diagnosis of MS, age ≥18 years, a membership for at least 1 year, and permission to receive mail from the association. In February 2014, recruitment letters including information about the study objectives, informed consent form (ICF), and a pre-paid envelope were mailed to a random sample of 1500 PwMS (drawn by an independent statistician) from a pool of 5408 PwMS registered with the Finnish Neuro Society, fulfilling the eligibility criteria. Recipients were informed that they could not participate if they were unable to complete the survey in Finnish language, were suffering from any illness other than MS that could limit their participation, or were recently enrolled in a clinical trial.

Data collection

The survey questionnaires were mailed to those who had provided informed consent by returning their signed ICF to the Finnish Neuro Society’s study center. Alternatively, the respondents could choose to provide the requested information via telephonic interview. The identity of PwMS was kept confidential and known only to the personnel of the study center. The answers were anonymously entered into a web-based data capturing system at the study center, using a patient-specific study identification. When necessary, the study nurse contacted the subjects by telephone in order to clarify missing or inconsistently written data.

The Finnish questionnaire was adapted from the one used in previous, multi-national studiesCitation7–10. The adaptations aimed to cover all MS-related resources that are commonly used by the PwMS in Finland. The questionnaire was subjected to pilot testing in a group of PwMS prior to study initiation. All data were collected through the questionnaire. Demographic background variables included age, gender, living conditions, employment status, sick leave, reduced income, and early retirement due to MS. Disease information included year of diagnosis, age at the onset of the first symptoms, type of MS, occurrence of relapses, and self-assessment of disease severity, assessed by the respondent-derived Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)Citation15. Relapses were defined as the clinical onset of new, recurrent or worsening of MS symptoms related to CNS dysfunction that lasted for at least 24 hours to weeks in absence of fever or infections. The EDSS instrument was translated into Finnish language by the authors (JR, HN) with the help of an authorised medical translator.

Questions on resource utilization covered all MS-related healthcare and non-medical consumptions and included questions on hospitalization, rehabilitation, outpatient visits to healthcare professionals, investigations/tests, use of DMTs, and other prescription medications, expenses on over-the-counter (OTC) medications, services from professional caregivers, informal care from family and friends, and use of new devices and major investments, such as transformations to the house or car or the purchase of a wheelchair or scooter. The patients were specifically asked to report only the MS-related resource consumptions.

Questions on productivity losses covered early retirement, reduced income, and sick leave due to MS.

In order to avoid open questions, all resources that are expected to be possible sources of costs due to MS were specified. In order to reduce recall bias, different recall periods were used for different items on the questionnaire. Thus, information on relapses, inpatient care, investigations/tests, and devises/investments was collected for the past year. A recall period of 3 months was set for short-term sick leave, outpatient care, consultations, and assistance required. A 1-month recall period was used for other medication use. For use of DMTs, information on current use was collected.

HRQoL data were collected using the generic EuroQol 5D-3L instrument (EQ-5D)Citation16. Patients’ responses to questions regarding the five domains of well-being (mobility, personal care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) were translated into utilities on a scale of 0 (death) to 1 (full health) using a social tariff established with the general population in the UK to ensure comparability with earlier studiesCitation17. In addition, the visual analog scale (VAS) assessed patients’ perceived health state on a scale of 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state).

Costs

Costs were estimated from the societal perspective and consisted of direct healthcare (inpatient and outpatient care, consultations with healthcare professionals, investigations/tests, DMTs and other medications), direct non-medical (professional and informal care, new devices/investments), and productivity costs (sick leave, reduced income, and early retirement due to MS).

The unit costs were derived from available public price listsCitation18,Citation19, with a few exceptions where approximations by experts of the respective field had to be relied upon, and reflected the consumer prices (€) in 2013 in Finland. Costs from earlier years were inflated to the 2013 level by using relevant price indexes published by Statistics FinlandCitation18.

The costs of resource use, collected using variable recall periods, were calculated by multiplying each resource with the relevant unit costs which were then annualized with the assumption that the resource consumption within that recall period is representative of similar recall periods throughout the year.

To obtain the costs of DMTs and other prescription medications, unit prices of the medications were derived from the public price list common to all pharmacies in Finland. Most medications were queried at group level, where the most commonly used products for given indications were listed as examples by both generic and brand names. The average annual or per day costs of prescription medications were calculated using the pack size, dosage strength, and recommended dose. The unit price of the most commonly used dosage was weighed by proportional use of each product, derived from IMS Health’s sales database. The list of DMTs included all first- and second-line DMTs available in Finland at the time of the study. To meet the Finnish regulatory requirements for a non-interventional study, brand names could not be asked. Instead, the PwMS were asked whether they were using first-line injectable therapies (beta-interferons and glatiramer acetate) or second-line therapies (fingolimod and natalizumab). Parity pricing among all first-line DMTs and only a minor price difference between second-line treatment options ensured the accuracy of the annual DMT cost estimates. The costs of expenses on OTC/non-prescription medications were calculated using costs indicated by patients.

The costs of transformation to the house due to MS were estimated by asking whether the changes could be considered as minor, moderate, or major. The average unit price at each level was calculated based on specified examples on most commonly made changes.

The informal care cost was assessed by using the replacement cost method, where average weekly hours of help needed from non-paid caregivers for various tasks were multiplied by the hourly wage of a respective professional caregiver.

Productivity losses were calculated only for patients who were employed (sick leave and reduced income) or who were <63 years of age and on early retirement due to MS. The most common retirement age in Finland, 63 years, was chosen as a limit for productivity loss calculations. The productivity losses were assessed using the human capital approach, where productivity was valued at the gender-specific annual gross salary of full-time employees, including the Finnish standard employers’ overhead costs (26% of the salary).

The cost of relapses was estimated from the difference in costs incurred by patients (RRMS) with at least one relapse during the past 12 months compared to those without a relapse. Only the patients with EDSS score ≤5 were considered for this analysis.

Data analysis

Risk of data entry errors was minimized by double data entry and automated edit checks built into the web-based data capturing system. All questions on resource use required a binary answer (yes/no), followed by more detailed questions on the type and quantity of each resource. In case of unanswered questions, a conservative assumption was made that the resource in question was not used. In situations where a patient had indicated “yes” to resource use, but had not specified the quantity, the mean quantities used for the same resource by patients with similar characteristics (EDSS, gender) were assigned. Analyses were carried out using the SAS 9.2 software package and were mainly descriptive. Confidence intervals (95%) were estimated by non-parametric bootstrapping. Given that the response variables were not normally distributed, non-parametric Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test for independent samples was used to determine whether between-group differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Regression models were applied to explore the impact of relapses on costs and QoL.

Results

Demographics and disease information

Overall, 553 patients (36.9% of those invited and 93.6% of those who returned signed ICF) completed the questionnaire and were included in the analysis. In terms of age and age at diagnosis, the study sample well represented the 1500 PwMS who were invited to participate, except a slightly higher representation of females in the final study sample (78.7% vs 74.1%).

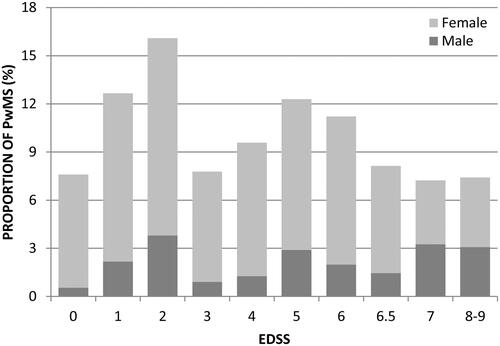

The study sample was representative of all ages, MS types and levels of disability. Sample demographics and disease characteristics are summarized in . The mean age was 53.8 years. A majority (76.1%) of patients were within the working age (below 63 years). The mean age at diagnosis was 37.4 years. Ten percent of patients were unable to define their disease type. The mean EDSS score of the study sample was 4.0. Distribution of patients across EDSS is shown in . DMT use was reported by 42.7% of the patients, with most reporting use of first-line DMTs.

Table 1. Sample demographics and disease characteristics (n = 553).

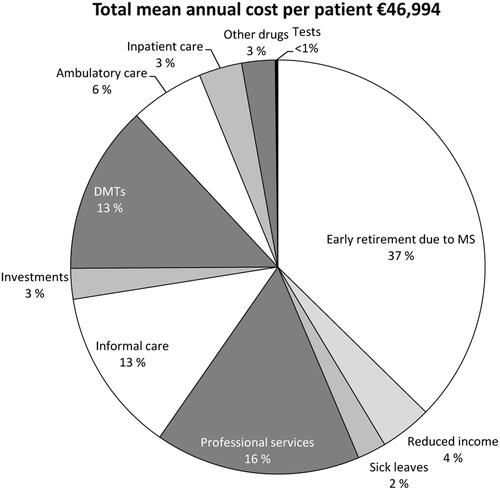

Total costs and direct healthcare costs

The total mean annual cost per MS patient in the study sample was estimated at €46,994. The distribution of costs across different type of resources is shown in . The estimated annual direct healthcare cost per PwMS accounted for 25.2% (€11,931) of the total costs. The annual direct healthcare costs per patient for each medical resource used are presented in . Approximately 43% of the patients reported DMT use, and it contributed the most to direct healthcare costs (13.2% of the total costs; €6185 per PwMS). In general, ambulatory care was the second most used medical resource and represented 5.8% of the total costs (€2851 per PwMS). Inpatient care (€1578 per PwMS) accounted for 3.4% of the total costs, of which, institutional rehabilitation, used by 18.3% of PwMS, was the main cost driver (€1212 per PwMS).

Table 2. Use of medical resources and estimated direct healthcare costs.

Direct non-medical costs

The annual mean direct non-medical costs (the use of investments and services) were estimated at €14,562 per PwMS (). Informal care was the main driver of non-medical cost, representing 12.8% of the total cost and used by 56.4% of the patients. On average, family or friends provided informal care for 10.5 h per week, corresponding to an annual cost per patient of €6035. Overall, professional services were used by 32.7% of the patients and accounted for 16.0% of the total costs. Communal transportation service was the most commonly used type of professional services. About one-fifth of the patients used services of the personal caregivers. Nearly half of all professional service costs were due to services from personal caregivers, who provided assistance on an average of 30.1 h per week. Approximately 21% of the patients had made investments which included modifications to the home or car or purchased devices such as wheelchairs/walking aids.

Table 3. Use of investments and services and estimated direct non-medical costs.

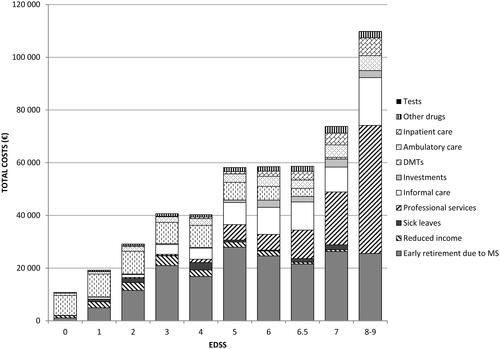

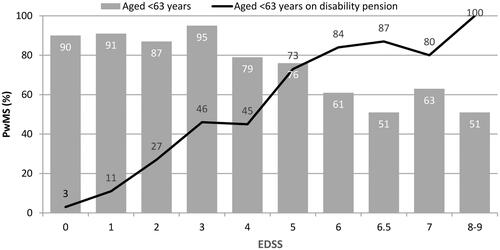

Impact of disease severity on costs

As demonstrated in , disease severity was strongly associated with impaired working capacity. Overall, more than half of the patients (n = 308; 55.7%) indicated to have retired early due to MS. Of these, 198 were still on disability pension, indicating that 35.8% of the patients below 63 years of age were on early retirement due to MS (in Finland, disability pension is converted to retirement pension once a person turns 63). The mean age at early retirement due to MS was 45.1 (SD = 8.8) years and the time to retirement from diagnosis and from the disease onset was 6.7 (SD = 6.4) years and 13.5 (SD = 8.5) years, respectively. In addition, 37.9% of the employed or self-employed patients had to change the type of work or reduce working hours, resulting in reduced income.

Figure 3. Effect of MS on working capacity: proportion (%) of PwMS below age of 63 of all patients in each EDSS category (bars) and proportion (%) of PwMS on disability pension due to MS of those below age of 63 (line).

As presented in and , the costs were strongly associated with disease severity and increased ∼10-fold from early disease (EDSS score 0; €10,835 per PwMS) to severe disease (EDSS score 8–9; €109,901 per PwMS), essentially due to the high requirement of professional services and informal care in the advanced disease stage. Thus, the proportion of direct non-medical costs to total costs increased from 0.5% in patients at EDSS score 0 (early disease) to 62.3% in patients at EDSS score 8–9 (severe disease).

Table 4. Costs and health-related quality-of-life per PwMS per year (€2013) by disease severity.

Productivity losses

Productivity losses due to early retirement, sick leave, and reduced income were estimated at €20,501 per PwMS, accounting for 43.6% of the total costs (; ). Early retirement due to MS thereby represented the main driver to productivity losses, corresponding to the mean annual cost of €17,552 per patient (37.4% of the total costs). The mean productivity costs increased steadily with increased disease progression, and were highest in patients with EDSS score 5.

Table 5. Productivity costs due to sick-leave, reduced income, and early retirement due to MS.

Impact of relapses on costs

Overall, 119 of the 553 (21.5%) PwMS across all disease types and severities had experienced relapses during the past year. The cost burden of relapses was estimated by comparing the annual costs of PwMS with RRMS and EDSS ≤5 who had experienced at least one relapse in the past year to those without relapse. Among the 216 PwMS with both RRMS and an EDSS score ≤5, 56 (25.9%) reported having had 1–10 relapses during the past 12 months. Relapses were associated with an incremental annual total cost of €20,081 per PwMS, which was mostly attributable to productivity losses (€11,297) and to a lesser extent to direct healthcare (€4061) and direct non-medical (€4723) costs. By dividing the excess cost with the mean number of 2.05 relapses reported, the mean total cost per relapse was estimated at €9778. However, PwMS with relapse(s) had a higher mean EDSS score (2.6) than those without relapse (1.8). This imbalance was controlled by estimating the differences in costs separately within each individual EDSS category up to EDSS score 5 and with regression analyses. In descriptive analysis, PwMS with relapses had consistently higher total costs than those without relapse. Two regression models with square root transformation to response variable were constructed to control for other variables and estimate statistical significance of the effect of relapses on total costs. The first regression model controlling for EDSS score (0–5), age, gender, and relapse status as explanatory variables predicted that the average effect of relapse on the total costs was €8311. Relapse had a statistically significant impact on total costs (p = 0.04). However, gender did not show a significant impact on the total cost and was, thus, excluded from the second model. The second model predicted with better accuracy that the average effect of relapse on the total costs is €7894. The relapse coefficient approached statistical significance (p = 0.0505). The impact of EDSS on total costs was highly significant (p < 0.001) in both models. Thus, relapses seem to have a probable trend-like effect on total costs, but statistical testing and absolute regression coefficient values suggest that disease severity has a markedly higher impact on total costs than relapses.

Health-related quality of life

The mean health state utility measured using EQ-5D in our sample was 0.644 (SD = 0.284) and the mean VAS score was 66.8 (SD = 19.6). The utility score decreased steadily with disease progression from 0.951 at EDSS 0 to 0.143 at EDSS 8-9 (). The mean scores on VAS decreased steadily from 90.1 at EDSS 0 to 56.7 at EDSS 5, stabilized thereafter, and again decreased to 47.2 at EDSS 8–9.

Relapses were associated with poor HRQoL. The effect of relapses on utility was estimated by comparing the EQ-5D utility scores of PwMS with RRMS and EDSS ≤5 who had experienced at least one relapse in the past year to those patients without relapse. Considering the skewed distribution of the EQ-5D utility values, non-parametric methods were used to assess the statistical significance of the observed differences. The non-parametric Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test demonstrated significantly lower mean health state utility among the PwMS with relapses compared to those without relapse (0.690 vs 0.824; p < 0.001). Subsequent analysis based on the bootstrap method confirmed the statistically significant difference of HRQoL between these groups (p = 0.002). Moreover, the mean VAS score was lower among PwMS with relapse than those without relapse (72.3 vs 79.0; p = 0.006). After controlling for the difference in disease severity by estimating the differences in HRQoL separately within each individual EDSS category up to EDSS score 5, utilities were consistently lower among PwMS with relapse in all individual EDSS categories, except in EDSS 4. In the regression model controlling for EDSS scores, the difference in EQ-5D utility values between PwMS with and without relapses was statistically significant (difference = 0.066; p = 0.012). This significant difference was verified by using the Tobit regression, which takes into account censored observations (difference = 0.064; p = 0.006).

Discussion

The DEFENSE study estimated the economic and HRQoL burden imposed by MS on PwMS and the society as a whole in Finland and also assessed its association with disease severity and relapses. Consistent with the findings from several studies from other countriesCitation5,Citation7–9,Citation11,Citation20, in Finland the total costs increased and the working ability as well as the HRQoL decreased in concert with disease progression. The mean annual cost per PwMS was estimated at €46,994. Losses in productivity due to early retirement contributed most to the total cost burden (37%), followed by the use of professional services (16%), use of DMTs, and informal care (both 13%). The total costs increased 10-fold from early disease (EDSS 0) to the stage of most severe disability (EDSS 8–9).

The study design, particularly the recruitment method, is likely to influence the study sample and should be taken into consideration while comparing the results with other studies and the general MS population. For example, a large multi-national, cross-sectional study in nine European countries adopted two approaches for sample selection: either through MS patients association or through neurology clinics. The results indicated that patients recruited from the MS patients associations had more severe disease and lower DMT use compared to those recruited from neurology clinicsCitation6. Our sample was drawn from the membership registry of the Finnish Neuro Society, the national patient association with coverage of ∼80% of the entire Finnish MS population. This may have resulted in selection of a sample with higher average disease severity (mean EDSS = 4.0) and a lower frequency of DMT use as compared to that in the multinational TRIBUNE study conducted recently in Europe and Canada, which recruited patients from specialized treatment centersCitation7–10. Therefore, potential comparisons to international studies should be performed among patients with similar levels of disease severity. The mean total annual costs of a PwMS with EDSS scores of 2 and 6.5 in this study were €29,232 and €58,623, respectively, which was consistent with earlier findings from nine other European countries. However, contribution of productivity losses to total costs among patients with EDSS 2 was markedly higher in our study than that in any other countryCitation6.

In the DEFENSE study, 37% of the patients responded to the questionnaire, which was comparable to that observed in the earlier European studyCitation6. The demographics of the 553 respondents with at least 40 PwMS in each EDSS category matched well with the randomly invited 1500 patients from the source population of 5408 members registered at the national patient association, except for a slight over-representation of females. The proportion of patients with RRMS in our sample was 44%, whereas that in a cross-sectional geographically based patient series has varied between 31–68% (mean = 57%)Citation21. Moreover, the distribution of PwMS across EDSS categories was non-linear and bimodal, similar to that reported in large prevalence studiesCitation22. The mean age at diagnosis (37 years) and the proportion of patients with PPMS (17%) were similar to those observed in a prevalence cohort of 240 patients in central Finland region (38 yearsCitation23 and 18%Citation24, respectively). The mean diagnostic latency from the onset of first symptoms was 5.7 years in the DEFENSE study and 5.2 years in the study conducted in central Finland. The female/male ratio of 3.6 in this study and that of 2.2 in studies from central Finland and Finnish Northern OstrobothniaCitation4 suggest a higher responder rates in females for surveys. Since gender did not seem to have significant impact on MS-related costs, the study sample, despite a higher proportion of females, can be justified as a representative of general MS population in Finland. Assuming ∼7000 PwMS in FinlandCitation3, the DEFENSE study estimates total annual costs of MS in Finland to be ∼€330 million.

According to the responses regarding employment, 56% of the PwMS indicated to have retired early due to MS at a certain stage of their life. In Finland, disability pension is generally converted to retirement pension at the age of 63 years. The proportion of working age population receiving disability pension due to MS (36% in the overall sample), therefore better describes the impact of the disease on work capacity. The proportion of patients on disability pension markedly increased from 3% to 46%, with an increase in EDSS score from 0–3, and contributed most to the cost increase in mild disease and explains the difference in cost structures in international comparisonsCitation6. Among the patients with an EDSS score of 5, the proportion of PwMS on disability pension increased markedly to 73%. The mean time to retirement was 13.5 years from the onset of MS symptoms and 6.7 years from diagnosis. This is in line with a prevalence study conducted in central Finland in 2000, wherein the mean duration from the onset of symptoms to disability pension was 9.1 yearsCitation24. Since PwMS with EDSS <4 commonly have only minor problems in ambulation, the reasons for early retirement may relate to other symptoms, such as fatigue and cognitive disorders. Workforce participation was much lower in the DEFENSE study than in patients with the same level of disability in the Swedish study of Berg et al.Citation11 . Finland and Sweden share the tradition of the Nordic welfare state, with a broad spectrum of publicly financed social and healthcare services available for the residents. In the absence of earlier burden-of-illness studies on MS from Finland, Sweden provides the most natural point of comparison despite variations in the organization of services. The high incidence of early retirement among Finnish PwMS suggests the need for more flexible work regulations and lower employment threshold to enable PwMS to continue working, despite their disease status. The results also highlight the need for choosing a societal perspective with inclusion of productivity losses, while evaluating the cost-effectiveness of MS treatments and other interventions.

The direct medical costs did not increase as much as the total costs in parallel to the disease severity. The use of DMTs was the main contributor to the direct medical costs at early disease stage, whereas inpatient hospitalization or rehabilitation contributed the most at advanced disease stages. Of note, despite the availability of new treatment options for MS, such as fingolimod and natalizumab, the proportion of patients using DMTs in the DEFENSE study (43%) remained similar to that in the burden-of-illness study conducted in Sweden almost 10 years agoCitation11. Intensive use of paid services and informal care contributed most to the overall cost increase in advanced disease stages. However, in contrast to the Swedish studyCitation11, the use of paid services contributed less to the total costs (Finland, 16% and Sweden, 28.5%). On the contrary, the contribution of informal care in the total costs was higher in Finland than that in Sweden (13% vs 9.2%). These differences can be explained by the use of full-time personal assistance in Sweden. In our sample, the use of personal assistance was considerabely lower and corresponded to an average 30.1 h per week. Despite having a similar proportion of users, the hours used for informal care were higher in Sweden, which could be partly attributable to differences in methods of valuing informal care among the countries. Instead of attempting to quantify the value of lost working hours or leisure time of caregivers, we chose a more straightforward replacement cost approach, wherein the cost of informal care was valued at the market price of the corresponding service. Reflecting the alternative ways services are arranged in the Finnish system and considering informal care unambiguously as direct cost, the method was expected to best serve decision-making in Finland. However, the cost of informal care should not be mixed up with the municipal care allowance for informal caregivers, which varies according to the level of commitment and intensity of care provided, but invariably under-rates its true market value.

Unlike costs, which are strongly influenced by the between-country differences in unit costs, the treatment practices, and the organization of healthcare systems, between-country comparison of the impact of MS on HRQoL is more feasible. The largest burden-of-illness study to date, by Kobelt et al.Citation6, demonstrated that the health state utilities among the MS patients were almost identical across the nine countries, a finding that was later confirmed by the TRIBUNE studyCitation7. In the DEFENSE study, the average utility decreased from 0.951 in patients with EDSS score 0 to as low as 0.143 in patients with EDSS score 8–9. This was in line with the Kobelt et al.Citation6 study, which used the same tariff for the EQ-5D instrumentCitation17, indicating the consistency of disease definition across the studies. The lower mean EDSS score compared to the Swedish sample of the Kobelt et al. study (4.0 vs 5.1), explains the higher mean utility scores in the DEFENSE study (0.644 vs 0.546)Citation11.

The impact of relapses on disease burden was assessed by comparing the PwMS with RRMS and EDSS score ≤5 who had indicated having experienced relapses during the past year with those without relapse. Consistent with the TRIBUNE studyCitation7–9, we assumed this sub-group to be clinically relevant, as the most common course of disease beyond EDSS score 5 is steady progression without relapseCitation25.

The results showed that relapses were associated with an incremental annual total cost of €20 081. In line with earlier studiesCitation6,Citation7, relapses were also associated with additional utility loss. However, the difference in effect on costs and utility between the PwMS with and without relapses was partially attributable to higher underlying disease severity among PwMS with relapses. When this imbalance was corrected using regression models, the effect of relapses on HRQoL (but not on the costs) remained statistically significant. Since the point estimates were of similar magnitude, regardless of the analysis method, it is possible that the observed trend-like effect on the costs could have reached statistical significance in a larger sample, which is very difficult to pre-specify in a burden-of-illness framework. Unexpectedly, relapses were reported across all levels of disability and disease types in this study. Therefore, the possibility that the PwMS had difficulties in differentiating between disease progression and relapse cannot be excluded.

Inherent to the study methodology, our survey study has some additional limitations. Even if the study sample seems representative of the general MS population in terms of measurable factors, an unobservable non-response bias is likely given the relatively low response rate. It is possible, for example, that the responders are more avid users of different resources than the non-responders. All information was collected directly from the PwMS, in whom the potential cognitive difficulties may emphasize general recall bias. The cost estimates relying on self-reporting by the patients should, therefore, be interpreted with caution. The fact that ∼10% of the respondents were unaware of their disease type indicates potential difficulties in self-assessment of the disease type. Furthermore, cross-sectional setting did not allow assessment of the significance of relapses in early MS or the use of DMTs on the prognosis of the disease. Prospective research is required to explore the long-term benefits and cost-effectiveness of various interventions, which aim at delaying disease progression, reducing relapse rate and improving overall HRQoL of PwMS.

Conclusions

This study contributes significantly to the existing literature on the burden of MS, confirming the findings of previous studies conducted in other countries that show that the total costs of MS increase and HRQoL decreases with worsening disability. High frequency of early retirement due to MS resulted in a substantial contribution of productivity costs to the total cost burden. This highlights the need to choose a societal perspective as the most appropriate perspective when economic efficiency of MS treatments is evaluated. Treatments that slow disease progression and help PwMS retain employment for a longer duration have the highest potential to reduce disease burden associated with MS.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The DEFENSE study was supported by Novartis Finland Oy and the Finnish Neuro Society.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

None disclosed. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript also have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anne Dahlberg and Anne Sinkkonen at Finnish Neuro Society for their contribution to data collection, and Arja Vainio at Smerud Medical Research Ab/Oy for study monitoring and oversight. The author’s also acknowledge Rahul Birari (Novartis Healthcare Pvt Ltd) for providing editorial support which comprised of checking content for language, formatting, and referencing, all under the direction of the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2008;372:1502-17

- Browne P, Chandraratna D, Angood C, et al. Atlas of Multiple Sclerosis 2013: a growing global problem with widespread inequity. Neurology 2014;83:1022-4

- Sumelahti ML, Tienari PJ, Wikstrom J, et al. Increasing prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Finland. Acta Neurol Scand 2001;103:153-8

- Krokki O, Bloigu R, Reunanen M, et al. Increasing incidence of multiple sclerosis in women in Northern Finland. Mult Scler 2011;17:133-8

- Henriksson F, Fredrikson S, Masterman T, et al. Costs, quality of life and disease severity in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study in Sweden. Eur J Neurol 2001;8:27-35

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, et al. Costs and quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis in Europe. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:918-26

- Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, et al. Treatment experience, burden and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS study: results from five European countries. Mult Scler 2012;18:7-15

- Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, et al. Treatment experience, burden, and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in multiple sclerosis: the costs and utilities of MS patients in Canada. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol 2012;19:e11-25

- Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, van Munster ET, et al. Treatment experience, burden, and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in Multiple Sclerosis study: the costs and utilities of MS patients in The Netherlands. J Med Econ 2013;16:939-50

- Karabudak R, Karampampa K, Caliskan Z, et al. Treatment experience, burden and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS study: results from Turkey. J Med Econ 2015;18:69-75

- Berg J, Lindgren P, Fredrikson S, et al. Costs and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in Sweden. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7(2 Suppl):S75-85

- Svendsen B, Myhr KM, Nyland H, et al. The cost of multiple sclerosis in Norway. Eur J Health Econ 2012;13:81-91

- Ellen N, Corbett J. International variation in drug usage: an exploratory analysis of the “causes” of variation. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2014. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR899. Accessed July 7, 2015

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, et al. Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis in Europe: method of assessment and analysis. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7(2 Suppl):S5-13

- Kurtzke JF. A new scale for evaluating disability in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1955;5:580-3

- EuroQoL Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199-208

- Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, et al. A social tariff for the UK: results from a UK population survey. University of York: Centre for Health Economics, 1995

- Statistics Finland, Helsinki, Finland, 2014. http://www.tilastokeskus.fi/. Accessed June 10, 2014

- Kapiainen S, Vaisanen A, Haula T. Terveyden- ja sosilaalihuollon yksikkökustannukset Suomessa vuonna 2011. Helsinki, Finland: Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos, 2014

- Kobelt G, Pugliatti M. Cost of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Eur J Neurol 2005;12(1 Suppl)1:63-7

- Confavreux C, Compston A. Chapter 4 - The natural history of multiple sclerosis. In: Compston A, Confavreux C, Lassmann H, et al., eds. McAlpine's Multiple Sclerosis, 4th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006. p 183-272

- Cohen JA, Reingold SC, Polman CH, et al. Disability outcome measures in multiple sclerosis clinical trials: current status and future prospects. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:467-76

- Sarasoja T, Wikstrom J, Paltamaa J, et al. Occurrence of multiple sclerosis in central Finland: a regional and temporal comparison during 30 years. Acta Neurol Scand 2004;110:331-6

- Paltamaa J, Sarasoja T, Wikstrom J, et al. Physical functioning in multiple sclerosis: a population-based study in central Finland. J Rehabil Med 2006;38:339-45

- Paz Soldan MM, Novotna M, Abou Zeid N, et al. Relapses and disability accumulation in progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2015;84:81-8