Abstract

Objective:

To determine annual biologic drug and administration costs to the US Veterans Health Administration (VHA) per treated patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis (PsO), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), or ankylosing spondylitis (AS) who received abatacept, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab, tocilizumab, or ustekinumab.

Methods:

Adults with at least one biologic claim between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2011 were included. Evidence of enrollment in the VHA was required from 365 days before (pre-index) to 360 days after (post-index) the date of the first biologic claim (index date). Included patients had pre-index diagnoses of RA, PsO, PsA, and/or AS. Drug costs were from Federal Supply Schedule or ‘Big Four’ in November 2014. Administration costs were VHA fixed costs for infused ($169) and subcutaneous ($25) biologics.

Results:

Of the 20,465 patients in the analysis, 10,711 received etanercept, 7838 received adalimumab, and 1196 received infliximab as the index biologic. In these patients, across all uses studied, the VHA incurred greater annual cost per treated patient for infliximab ($18,066) compared with adalimumab ($16,523) and etanercept ($16,526). In the first year post-index, ∼80% of patients were either persistent on these index biologics or re-started these index biologics after a ≥45–day treatment gap. Other biologics comprised <5% of the study population, with sample sizes ranging from 3–374 patients each. Cost by indication for biologics used by >20 patients ranged from $15,056 (etanercept) to $17,050 (abatacept) for RA; $16,697 (adalimumab) to $33,163 (ustekinumab) for PsO; $15,035 (etanercept) to $20,465 (infliximab) for PsA; and $14,239 (etanercept) to $18,536 (infliximab) for AS.

Limitations:

The model was limited to the VHA. Results for biologics other than adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab were difficult to interpret because of small sample sizes.

Conclusions:

Infliximab has higher cost to the VHA than adalimumab or etanercept.

Keywords::

Introduction

Immune-mediated inflammatory conditions, which are highly prevalent, are often treated with biologics. Approximately 1.5 million adults in the US have rheumatoid arthritisCitation1, an inflammatory autoimmune condition that primarily affects the lining (synovial membrane) in the joints of the bodyCitation2. Approximately 6.7 million adults in the US have psoriasisCitation3, a chronic, immune-mediated, often disabling inflammatory skin disease associated with varying degrees of severity and disabilityCitation4. The psoriatic plaque is characterized by skin that is dry, thickened, scaling, and red or silvery white. Lesions may be located anywhere on the body and may vary from a few small plaques to widespread, thickened, scaly red plaques. Approximately 1% of adults in the US have psoriatic arthritisCitation5, which is an autoimmune condition that most severely affects the fingers, toes, and spineCitation6. It is usually debilitating, as measured by standard quality-of-life metricsCitation7. Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic inflammatory disorder in a group of diseases called spondyloarthropathies. Its prevalence in the US is estimated to be ∼30 per 10,000 adultsCitation8, or between 0.6–2.4 million adultsCitation9. Because it is difficult to diagnose in the early stagesCitation10, it is considered the most overlooked cause of persistent back pain in young adults.

In the US, biologics including abataceptCitation11, adalimumabCitation12, certolizumab pegolCitation13, etanerceptCitation14, golimumabCitation15, infliximabCitation16, rituximabCitation17, tocilizumabCitation18, and ustekinumabCitation19 have been approved for use in one or more of these conditions (). Biologics help to modify the body’s inflammatory process and inhibit damage in autoimmune conditionsCitation20. The biologics differ in their method of administration (subcutaneous and/or intravenous), dosing, target molecule, approved indications, half–life, immunogenicity, efficacy for co-morbid conditions, availability within a health plan or formulary, and whether they are used first-line after failure of a non-biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) or after failure of both a non-biologic DMARD and another biologic.

Table 1. Biologic routes of administration and months of approval for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis, and ankylosing spondylitis indications in the US.

Understanding the relative cost of biologics can improve resource allocation from a payer’s perspective. Previous studies have used budget impact models and claims databases to evaluate utilization and costs associated with biologics in commercially insured patientsCitation21–27 or Medicaid patientsCitation28. This model has not been applied to the national Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which is a large purchaser of biologics. The objective of this study was to evaluate treatment patterns and annual treatment costs of biologics across indications in the VHA.

Methods

Patient selection

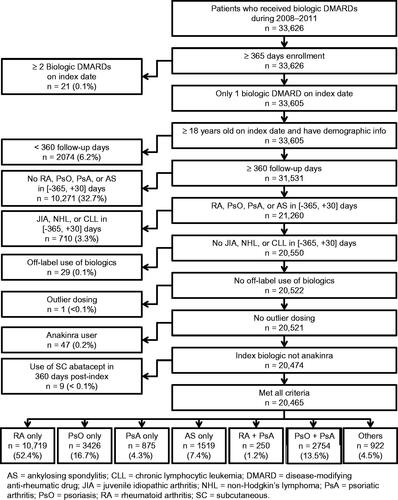

VHA databases were used to identify adult patients (age ≥18 years) with ≥1 claim for a biologic (abatacept, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab, tocilizumab, or ustekinumab) between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2011. The patient’s first biologic claim during this period that occurred after at least 1 year (365 days) of VHA enrollment was defined as the index claim. Patients were also required to have system activity ≥360 days after the index date; this period was defined as the post-index period. Patients were required to have at least one diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] 714.0x), psoriatic arthritis (696.0x), psoriasis (696.1x), or ankylosing spondylitis (720.0x) between 365 days before the index date and 30 days after the index date.

Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease (555.xx), ulcerative colitis (556.xx), juvenile idiopathic arthritis (714.3x), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (200.xx, 202.xx), or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (204.1x) between 365 days before the index date and 30 days after the index date. The index date could not occur before Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for that indication () or if their calculated weekly dose was more than twice the maximum recommended dose in the US package insertCitation11–19. Patients were also removed from the analysis if there was a claim for more than one biologic of interest on the index date or incomplete demographic information.

Data sources

Data were analyzed from three pharmacy sources housed in the Veterans Administration (VA) Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI): pharmacy benefits management (PBM), decisions support system (DSS), and corporate data warehouse (CDW). VINCI is a research and development environment jointly funded by Health Services Research & Development Service and the Office of Information and Technology. Other data housed in VINCI include data on inpatient and outpatient encounters. Data from the three pharmacy sources (PBM, DSS, and CDW) were reviewed to confirm consistent identification of the study populationCitation29.

Days of medication supply, units dispensed, directions for use, and dispensing dates were used to infer time on a medication and calculate cumulative dose. The VA pharmacy data have some data-entry errors in days of medication supply and units dispensed that result in improbable prescription duration and total dose dispensed. This is particularly problematic with injectable agents. Thus, an error detection and correction algorithm for DMARDs was developed for the Veterans Affairs Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry (VARA)Citation30–32. A similar algorithm was used for biologics in this study. The algorithm calculated the duration of each prescription dispensed, as follows. The first step calculated the average weekly dose (AWD) from the days supplied, unit strength, and number of units dispensed. If the AWD was consistent with the dosing recommendations in the package insert, then the information for days of medication supply was assumed to be accurate and was used to calculate the expected duration of that dispensing. If the AWD was too low or too high, then the total amount of drug dispensed (number of units dispensed multiplied by the unit strength) was divided by the standardized weekly dose from narrative medication schedules from prescriptions (Sigs) and multiplied by 7 days to obtain the estimated days of medication supply. A natural language processing tool to extract information from multiple Sigs was developed and validatedCitation30,Citation31,Citation33.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were descriptive and hypothesis testing was not performed. Biologic cost was calculated based on the quantity of each agent used (in milligrams), followed by application of unit biologic drug cost per milligram of each agent. The quantity used was the total amount dispensed, summed across all pharmacy and medical claims, with an allowed amount (i.e., amount paid) greater than zero. Unit biologic drug costs as of November 2014 were based on the Federal Supply Schedule cost for adalimumab or certolizumab pegol; and ‘Big Four’ (VHA, Department of Defense, Public Health Services, and the Coast Guard) cost for abatacept, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab, tocilizumab, and ustekinumab. VHA-specific fixed fees were applied for dispensing a subcutaneously administered biologic ($25) or for administering an intravenously infused biologic ($169); patient co-payments were not applied for >99% of patients and, thus, were not deducted from drug costs. If the duration of benefit extended beyond the 360-day post-index period, only the applicable portion of the last dose was included in the cost. When a patient switched to another biologic during the post-index period, the model attributed the costs of all non-index biologics to the index drug.

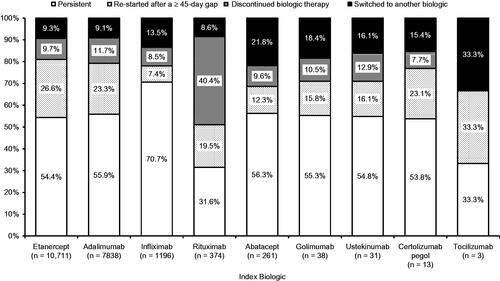

Patients were classified according to one of four possible biologic treatment patterns during the 360-day post-index period: persistent, re-started the index biologic, switched to another biologic, or discontinued biologic therapy. The duration of clinical benefit was assumed to be as follows, based on the prescribing information for each biologic: abatacept, 4 weeks; adalimumab, 2 weeks; certolizumab pegol, 2 weeks for each 200 mg syringe and 4 weeks for each 400 mg syringe; etanercept, 1 week for each 50 mg syringe and 0.5 weeks for each 25 mg syringe; golimumab, 4 weeks; infliximab, 8 weeks for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and psoriasis, and 6 weeks for ankylosing spondylitis; rituximab, 24 weeks; tocilizumab, 4 weeks; and ustekinumab, 12 weeks. Patients were classified as persistent if they had no ≥45-day gap in index biologic therapy after the end of clinical benefit from the previous dose and did not switch to another biologic. Patients were classified as re-starting their index biologic if they had a ≥45-day gap and then had another claim for their index biologic without receiving another biologic of interest within this gap. Patients were classified as switching if they received another biologic of interest during the post-index period. Patients were classified as discontinuing biologic therapy if after a ≥45-day gap they received no other biologic. The ≥45-day gap was selected based on previous publications that used a similar approach to analyze biologic treatment patternsCitation21,Citation23,Citation28,Citation34.

Analyses were stratified by index biologic and indication. Analyses were further stratified by new users and established users. New users were defined as patients without a claim for the index drug during the 180-day pre-index period. Established users were defined as patients with at least one prior claim for the index drug in the 180-day pre-index period.

Results

A total of 33,626 VA patients with biologic exposure were identified, with 20,465 patients included in the analysis (). The most common reason for attrition from the study sample (32.7%) was no reported diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis, or ankylosing spondylitis in the pre-index period. No patient was removed from the analysis because of <365 days of enrollment pre-index, and 6.2% were removed from the analysis because of <360 days of follow-up. Most patients received etanercept (n = 10,711), adalimumab (n = 7838), or infliximab (n = 1196) as the index biologic, followed by rituximab (n = 374), abatacept (n = 261), golimumab (n = 38), ustekinumab (n = 31), certolizumab pegol (n = 13), and tocilizumab (n = 3).

Most patients (71–93% by condition) were >45 years of age, and the population was predominantly male (88–97% by condition) (). Approximately half of the patients were established users who were treated with the biologic before the index date. Mean body weight at index by condition ranged from 91.4 kg (standard deviation [SD] = 20.5) for rheumatoid arthritis to 100.4 kg (SD = 21.7) for psoriasis (). Mean (SD) body weight by index biologic for all conditions combined was as follows: etanercept, 95.1 kg (20.6); adalimumab, 94.8 kg (21.7); infliximab, 93.7 kg (20.6); rituximab, 89.6 kg (20.2); abatacept, 93.7 kg (22.9); golimumab, 90.4 kg (20.6); ustekinumab, 97.3 kg (23.6); certolizumab, 97.2 kg (28.8); and tocilizumab, 117.6 kg (33.7).

Table 2. Patient characteristics at index date.

The percentages of patients who were either persistent on the index biologic or who re-started the index biologic after a ≥45-day gap were as follows: etanercept, 81.0%; adalimumab, 79.2%; infliximab, 78.1%; rituximab, 51.1%; abatacept, 68.6%; golimumab, 71.1%; ustekinumab, 70.9%; certolizumab pegol, 76.9%; and tocilizumab, 66.7% (). Other patients either discontinued biologic therapy after a treatment gap or switched to another biologic during the 360-day post-index period. Similar results were seen for treatment patterns by condition (). Most patients who switched to a different biologic switched to a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (etanercept, adalimumab, or infliximab) ().

Table 3. Treatment patterns over 360 days by index biologic and by condition.

Table 4. Most common biologic switches by index biologic (all patients combined).

The cost per treated patient across all four conditions (alone or in combination) was $16,523 for adalimumab, $16,526 for etanercept, and $18,066 for infliximab (). Of these three biologics, the cost per treated patient was lowest for etanercept for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis, and was lowest for adalimumab for patients with psoriasis. For adalimumab and infliximab, annual costs were generally similar across conditions, but were higher for established users than for new users of these biologics. Annual costs for etanercept were generally similar both across conditions and between new and established users, with the exception of new users of etanercept with psoriasis alone, who had higher costs than those with other conditions and established users.

Table 5. Annual biologic cost* per treated patient by index biologic and by condition.

Discussion

In this analysis, biologic use in the VHA was focused on three drugs—etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab—for patients with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or any combination of these conditions. Approximately 80% of patients were persistent with etanercept, adalimumab, or infliximab through the 1-year follow-up period with or without a gap in therapy; the other 20% were evenly balanced between complete discontinuation of biologic therapy and switching to another biologic therapy. Biologic costs, including drug costs and dispensing/administration costs, for infliximab were higher than for etanercept or adalimumab from the VHA perspective across all of the studied conditions and within each condition.

Etanercept and adalimumab had similar annual costs per treated patient. Compared with adalimumab, the cost per treated patient for etanercept was lower in rheumatoid arthritis by 9%, in psoriatic arthritis by 6%, and in ankylosing spondylitis by 4%, and higher in psoriasis by 21%. Because the analysis was stratified by new users (those with no biologic use in the pre-index period) and established users (those with biologic use in the pre-index period), it was possible to examine costs separately in these populations. These analyses revealed that the annual cost of etanercept treatment was greater during the first year of new use compared with established use, particularly in patients with psoriasis. This finding is consistent with the recommended dosing for etanercept, which is administered once weekly for most conditions but can be administered twice weekly in patients with psoriasis for the first 3 months, and then once weekly thereafterCitation14. During the period of this analysis, loading doses were also approved during treatment initiation for ustekinumab (in psoriasis), adalimumab (in psoriasis), and infliximab (in all of the conditions studied), which may have increased costs for new users with these conditions as compared to established users. In contrast, the annual costs per treated patient for adalimumab and infliximab were 10% and 6% greater, respectively, in established users compared with new users. These findings were consistent with recommended dosing, because the doses of adalimumab (in rheumatoid arthritis) and infliximab (in all of the conditions studied) may be increased over time as needed to maintain efficacy in established usersCitation12,Citation16.

The observed treatment patterns and costs of etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab in this study were similar to those reported previously for patients with commercial insurance or Medicaid coverageCitation21–28. This was the first analysis of biologic costs to use data from the national VHA. The VHA has a number of characteristics that make it difficult to generalize from managed care data. These characteristics include patients being predominantly older males, physicians being on salary, and medication prices being governed by the Federal Supply Schedule or ‘Big Four’ pricing. The previous analyses excluded patients >63 years of ageCitation21–28 because these patients would become eligible for Medicare during the 1-year follow-up period and, thus, would not have the continuous enrollment necessary for the analysis. Older patients can continue to receive healthcare in the VHA after age 64 years. Younger patients in the VHA are also likely to maintain VA benefits and unlikely to switch to another health plan. This may explain why 94% of patients received healthcare in the VHA system during the 360-day post-index period of this analysis. In the previous analyses in commercially insured or Medicaid populations, as many as 32% of patients were removed from the analysis because of incomplete post-index follow-upCitation23,Citation28.

A previous VHA analysis evaluated dose escalation and estimated biologic costs for etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab in 563 patients with rheumatoid arthritis by using the VARA registry and linked VHA administrative databasesCitation33. In that analysis, annual costs for new biologic treatment were higher for infliximab ($16,900) than for adalimumab ($13,100) or etanercept ($13,500), despite similar effects on clinical disease activity for all three biologics. The current analysis extended those previous findings to the national VHA population and other immune-mediated inflammatory conditions or combinations of conditions.

This analysis used index dates through 2011. Newer biologics that were approved for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis during 2009–2010 (golimumab, certolizumab pegol, and tocilizumab) were included. However, less than 0.1% of patients (20, nine, and three patients, respectively) in the VHA who met all of the study inclusion criteria received one of these biologics. It is possible that the low exposure to these biologics was related to physician reluctance to use newer products or due to formulary restrictions, but the database did not include the reason for biologic selection.

Our analysis has some limitations. The model was limited to patients in the VHA, which is a predominantly male and older population. Mean body weight by condition in this analysis was between 90 and 100 kg; patients in other populations may be heavier or lighter, which could affect the costs of biologics such as infliximab and ustekinumab that are dosed according to body weight. Our data did not include assessments of the efficacy and/or safety of these products. No inferences regarding comparative efficacy or safety can be drawn. The model assumed that the index biologic was prescribed to treat diagnoses from claims data and was not validated with diagnoses in medical records. The model did not include the costs of non-biologic medications, such as methotrexate, which were expected to be very small relative to biologic costs and were not expected to have a substantial effect on total costs. When a patient switched to a different biologic in the 360-day post-index period, the biologic costs for the post-index biologic were attributed to the index biologic. Patients who received a different biologic during the pre-index period were not excluded from the analysis, which may have complicated the attribution of costs to the index biologic. Patients were considered to be new users of biologics if they had no claim for another biologic in the previous 6 months. Some of the new users could have received biologic treatment before that period, but it is unlikely that many patients with previous biologic treatment had a >6-month gap in therapy and then re-started the same biologic. The model estimated the financial impact of biologics based on real-world use, including amount of drug used, dosing intervals, discontinuation and re-starting, and switching between biologics. Real-world use may not reflect FDA-approved indications and dosing. Clinical practice patterns and/or patient medication behaviors may vary. For example, real-world use of biologics may include dose reduction or dose spacing, particularly later in the course of therapy, and this analysis included only the first year post-index. Treatment patterns and biologic costs in the VHA were difficult to interpret for other biologics because of the much smaller sample sizes.

Conclusions

Etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab accounted for more than 95% of the biologic use between 2008–2011 among more than 20,000 VHA patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis, and/or ankylosing spondylitis. The biologic cost to the VHA, including drug and administration cost, was greater for infliximab than for etanercept or adalimumab. These findings are similar to those reported previously in other populations, including commercially insured and Medicaid populationsCitation21–28, as well as in a smaller population of VHA patientsCitation33.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was funded by Amgen Inc. Supplemental funding was provided by a Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Award (HIR-08-204)—project title: Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI).

Declaration of financial/other relationships

NS, DJH, and DHT are employees and stockholders of Amgen Inc.

Acknowledgments

Jonathan Latham of PharmaScribe, LLC (on behalf of Amgen Inc.) and Julie Wang of Amgen Inc. provided assistance with the drafting and submission of the manuscript.

Previous presentations

Portions of this work were presented at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy 27th Annual Meeting & Expo, San Diego, CA, USA, April 7–10, 2015.

References

- Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, et al. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: Results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955–2007. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:1576-82

- Meier FM, Frerix M, Hermann W, et al. Current immunotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunotherapy 2013;5:955-74

- Helmick CG, Lee-Han H, Hirsch SC, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the U.S.: 2003–2006 and 2009–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Am J Prev Med 2014;47:37-45

- Kircik LH, Del Rosso JQ. Anti-TNF agents for the treatment of psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol 2009;8:546-59

- Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, et al. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64(2 Suppl):ii14-17

- Day MS, Nam D, Goodman S, et al. Psoriatic arthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2012;20:28-37

- Rosen CF, Mussani F, Chandran V, et al. Patients with psoriatic arthritis have worse quality of life than those with psoriasis alone. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:571-6

- Dean LE, Jones GT, MacDonald AG, et al. Global prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:650-7

- Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:15-25

- Raychaudhuri SP, Deodhar A. The classification and diagnostic criteria of ankylosing spondylitis. J Autoimmun 2014;48–49:128-33

- ORENCIA® (abatacept) Prescribing Information. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, 2015

- Humira® (adalimumab) Prescribing Information. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc., 2014

- CIMZIA® (certolizumab pegol) Prescribing Information. Smyrna, GA: UCB, Inc., 2013

- Enbrel® (etanercept) Prescribing Information. Thousand Oaks, CA: lmmunex Corporation, 2015

- SIMPONI® (golimumab) Prescribing Information. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc., 2014

- Remicade® (infliximab) Prescribing Information. Malvern, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc., 2015

- RITUXAN® (rituximab) Prescribing Information. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc., 2014

- ACTEMRA® (tocilizumab) Prescribing Information. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc., 2014

- STELARA® (ustekinumab) Prescribing Information. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc., 2014

- Rosman Z, Shoenfeld Y, Zandman-Goddard G. Biologic therapy for autoimmune diseases: an update. BMC Med 2013;11:88

- Bonafede MM, Gandra SR, Watson C, et al. Cost per treated patient for etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab across adult indications: a claims analysis. Adv Ther 2012;29:234-48

- Bonafede M, Joseph GJ, Princic N, et al. Annual acquisition and administration cost of biologic response modifiers per patient with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis. J Med Econ 2013;16:1120-8

- Howe A, Eyck LT, Dufour R, et al. Treatment patterns and annual drug costs of biologic therapies across indications from the Humana commercial database. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014;20:1236-44

- Joyce AT, Gandra SR, Fox KM, et al. National and regional dose escalation and cost of tumor necrosis factor blocker therapy in biologic-naive rheumatoid arthritis patients in US health plans. J Med Econ 2014;17:1-10

- Schabert VF, Watson C, Gandra SR, et al. Annual costs of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors using real-world data in a commercially insured population in the United States. J Med Econ 2012;15:264-75

- Schabert VF, Watson C, Joseph GJ, et al. Costs of tumor necrosis factor blockers per treated patient using real-world drug data in a managed care population. J Manag Care Pharm 2013;19:621-30

- Wu N, Lee YC, Shah N, et al. Cost of biologics per treated patient across immune-mediated inflammatory disease indications in a pharmacy benefit management setting: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Ther 2014;36:1231-41, 41 e1–3

- Bonafede M, Joseph GJ, Shah N, et al. Cost of tumor necrosis factor blockers per patient with rheumatoid arthritis in a multistate Medicaid population. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2014;6:381-8

- Fihn SD, Francis J, Clancy C, et al. Insights from advanced analytics at the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1203-11

- Nelson SD, Lu CC, Teng CC, et al. The use of natural language processing of infusion notes to identify outpatient infusions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24:86-92

- Lu CC, Leng J, Cannon G, et al. Accuracy of a natural language processing software designed to compute average weekly dose from narrative medication schedule [abstract]. Value Health 2014;17:A187-8

- Cannon GW, Mikuls TR, Hayden CL, et al. Merging Veterans Affairs rheumatoid arthritis registry and pharmacy data to assess methotrexate adherence and disease activity in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:1680-90

- Cannon GW, DuVall SL, Haroldsen CL, et al. Persistence and dose escalation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1935-43

- Bonafede M, Fox KM, Watson C, et al. Treatment patterns in the first year after initiating tumor necrosis factor blockers in real-world settings. Adv Ther 2012;29:664-74